As part of Medidays, the week-long internal medicine training program of the University Hospital Zurich (USZ), one afternoon was also devoted to various oncology topics. In multiple myeloma and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, new agents and therapeutic modalities have been developed in recent years that have improved the prognosis of patients. The results for cancer screening are less positive: a lot of effort does not automatically mean a lot of success.

(ee) Prof. Dr. med. Bernhard Pestalozzi, Head Physician of the Clinic for Oncology at the USZ, spoke about the contradictory aspects of measures for early cancer detection.

He began with a case example: you receive a call from a good friend who excitedly tells you that a suspicious finding came up in his wife’s screening mammogram. Now, what is the risk that this incidental finding actually corresponds to invasive breast carcinoma?

Relative and absolute risk reduction in breast cancer screening.

The opinions in the audience were widely scattered: some said the probability was 90%, others assumed 1%.

In fact, the risk is around 10%: Of every 1000 women who undergo screening mammography every two years for ten years, around 200 have to have an abnormal finding clarified, which entails physical and psychological stress. About 24 are eventually diagnosed with breast cancer.

However, breast cancer is also not detected in four to seven women; thus, a negative mammogram does not mean 100 percent certainty that breast cancer is not present. In a group of 1000 non-screened women, five ultimately die of breast cancer; in a group of 1000 screened women, four still do.

Thus, the relative risk of dying from breast cancer is reduced by 20% through screening, but the absolute risk reduction is only 0.1% (only one in 1000 screened women actually benefits from the risk reduction). The figures listed here are available on the fact sheet of the Swiss Cancer League, which advocates screening (https://assets.krebsliga.ch/downloads/1451.pdf).

These “poor” mammography screening numbers improve for women at higher than average risk of breast cancer and with the use of better screening techniques. For example, 3D mammography detects 30% more carcinomas, and the recall rate is 30% lower. Mamma MRI, which is recommended for patients with BRCA mutations, also has higher sensitivity (but even lower specificity).

PSA determination and colorectal cancer screening: What makes sense?

In prostate cancer screening, the record does not look any better. Out of 1000 men who have PSA screening every one to four years for ten years, 100-120 get a false-positive result, meaning they are screened by biopsy and do not have prostate cancer, but any side effects of the biopsy, such as pain and anxiety. Another 110 are actually diagnosed with prostate cancer and subsequently treated probably in the majority, with the possible side effects on urinary continence and sexual function. Overall, however, screening 1000 men will prevent at most one death from prostate cancer. Therefore, general PSA screening is not recommended by the American Task Force. The Swiss Society of Urology recommends PSA testing only for patients with a family history of prostate cancer (45 years of age or older) and when requested by an informed male (between 50 and 70 years of age).

The situation is more favorable for colon cancer screening, which has been covered by basic insurance since June 2013. Reimbursement is for a stool test every two years and/or a colonoscopy every ten years (for 50- to 69-year-olds). For both stool testing and sigmoidoscopy/colonoscopy, there is good evidence that this reduces the incidence and mortality of colorectal cancer. Regarding mortality reduction by colonoscopy screening, one must extrapolate from the randomized trials of sigmoidoscopy. To prevent one death from colorectal cancer, 300 to 600 screening colonoscopies are needed.

Update on diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

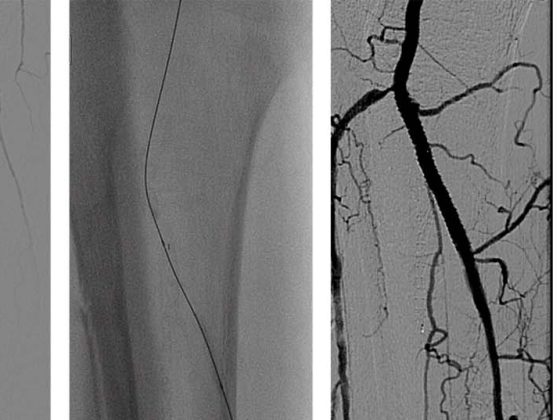

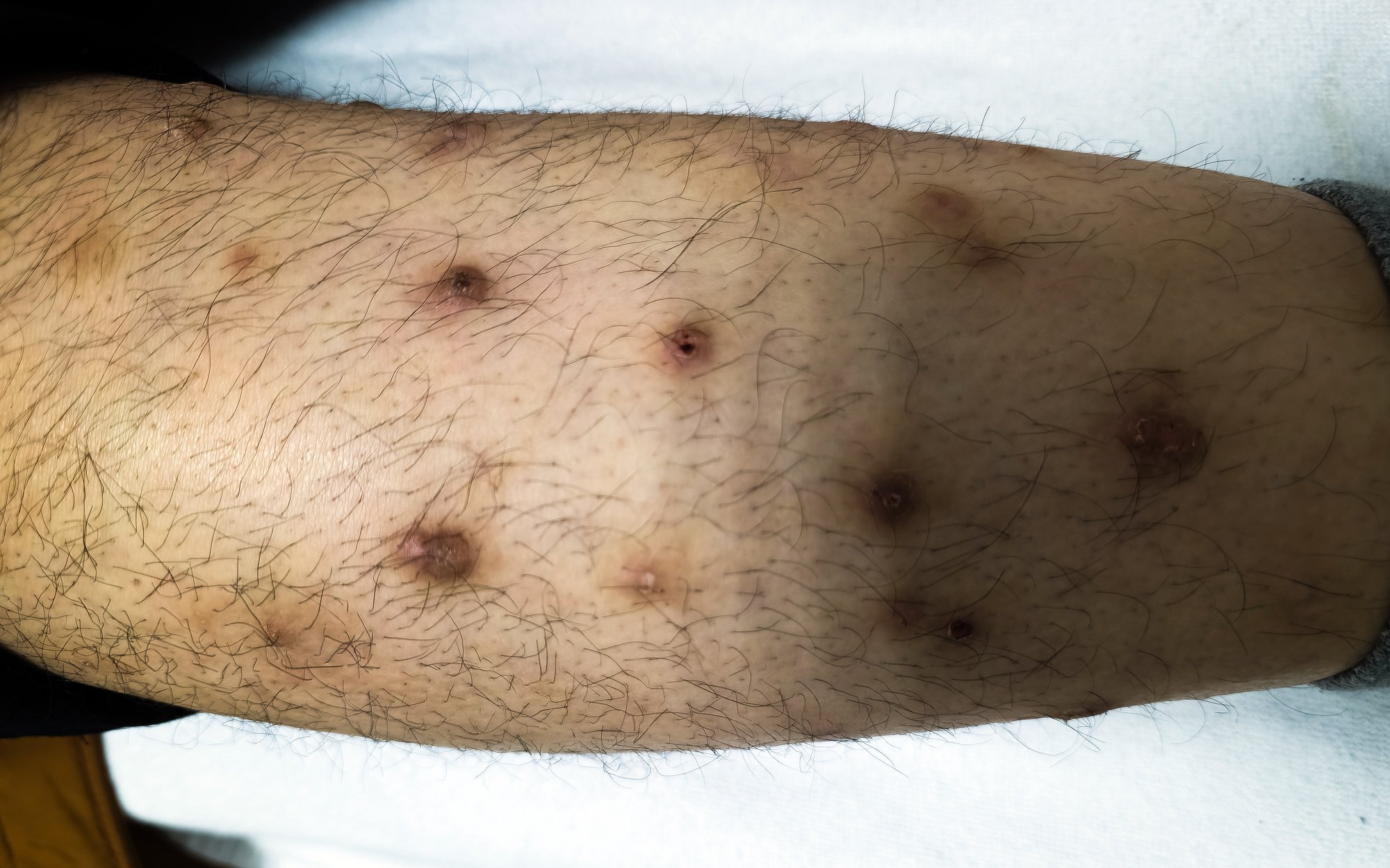

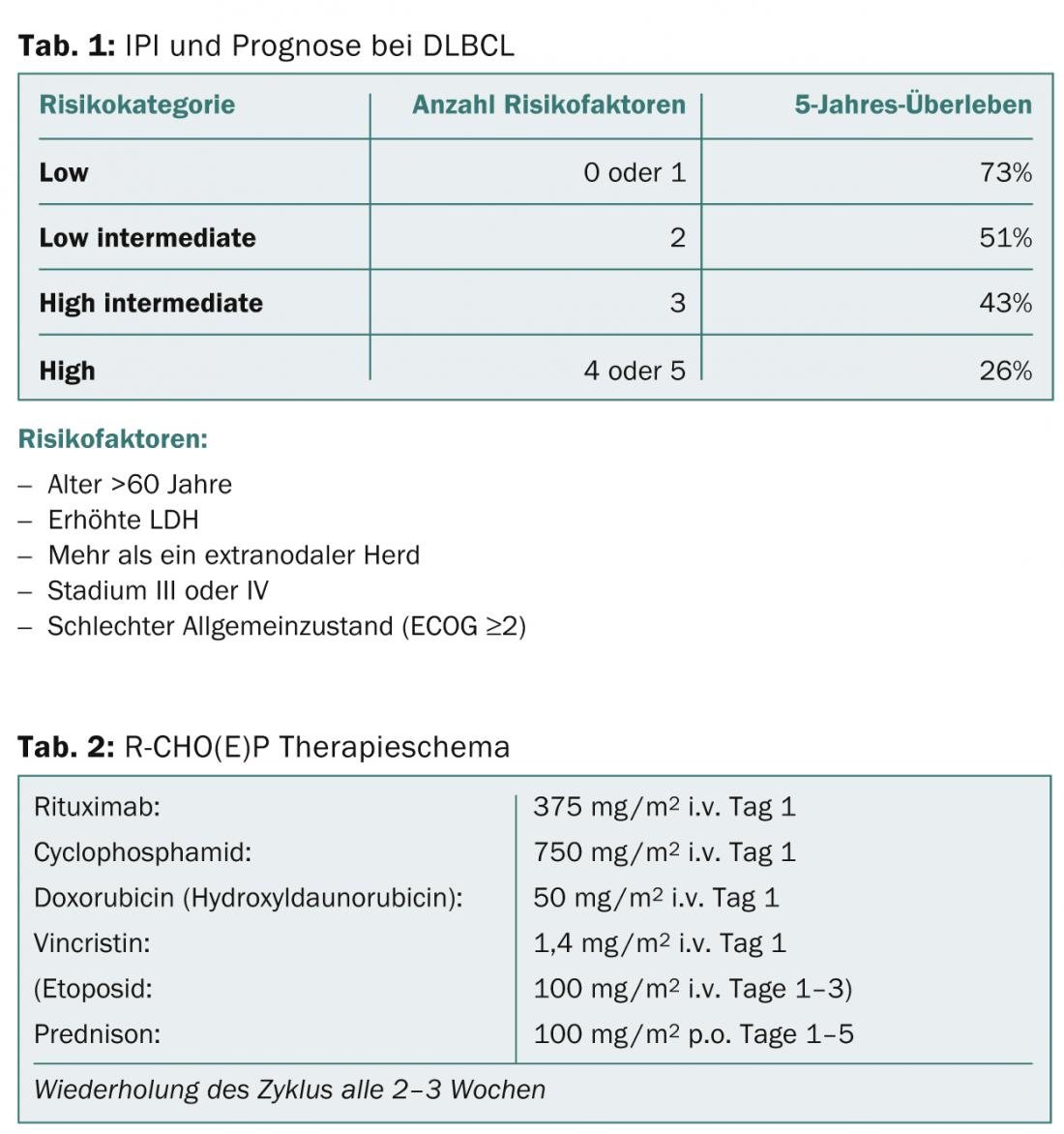

Panagiotis Samaras, MD, senior physician at the Department of Oncology at the USZ, provided an overview of two common hematologic diseases: diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and multiple myeloma (MM). DLBCL is the most common lymphoma of all. Prognosis and therapy strongly depend on the number of risk factors assessed by the International Prognostic Index (IPI) (Table 1). Patients between 18 and 60 years of age with an IPI <2 are considered young and low-risk. Their survival rates are over 90%. In patients younger than 60 years with an IPI ≥2, who are classified as high-risk, survival rates are approximately 50%. Patients are treated with the R-CHOP regimen (Table 2), with a varying number of cycles (6-8 cycles are standard) depending on the age of the patient and risk factors, and with the addition of etoposide if necessary.

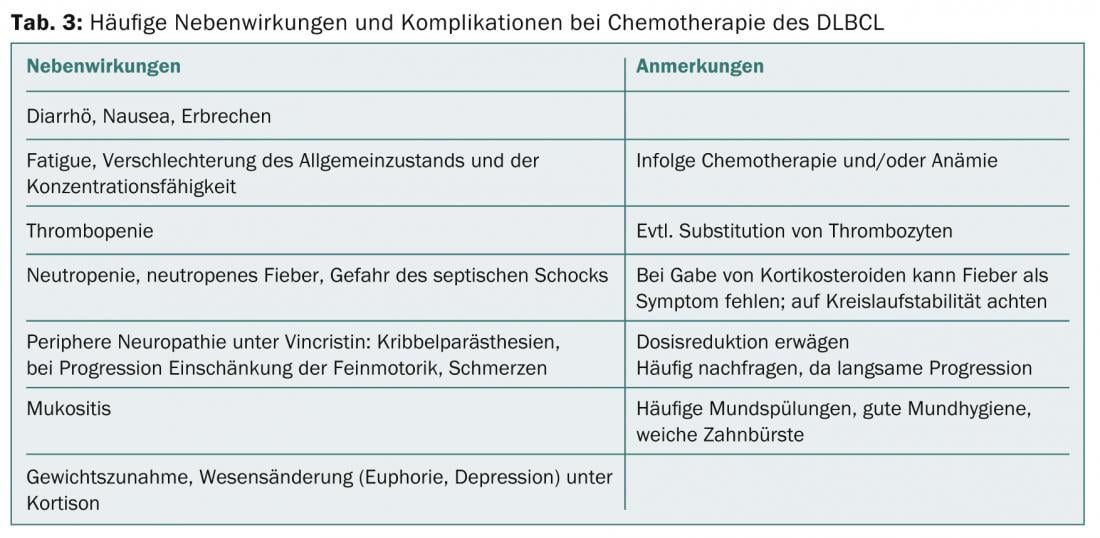

During chemotherapy, a clinical check-up and a blood count check-up are performed every week. In a 14-day therapeutic regimen, patients receive antibiotics to control infection and G-CSF to shorten the duration of neutropenia. In case of side effects (Tab. 3), ambiguities or complications, the patients resp. the general practitioner can make low-threshold contact with the oncologist – even at night or on weekends. If a relapse of DLBCL occurs, autologous stem cell transplantation is the next option after high-dose chemotherapy.

Multiple Myeloma – New Therapy Options

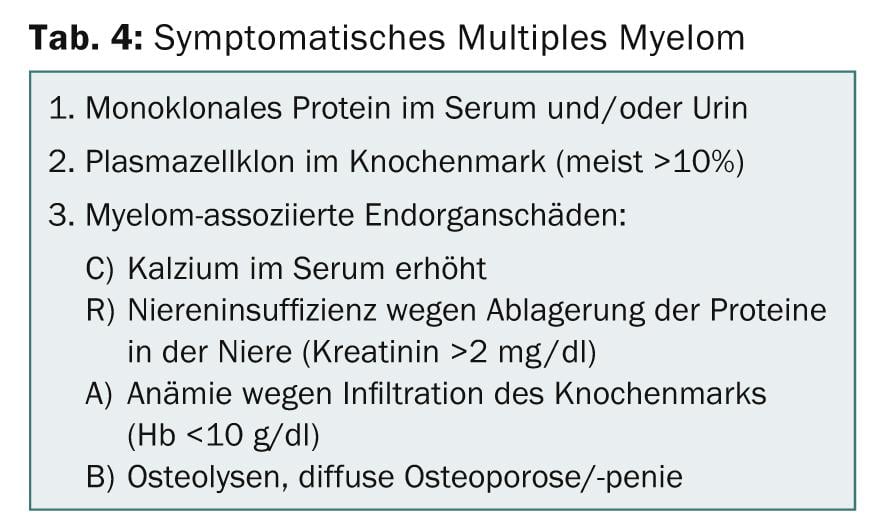

Multiple myeloma (MM) is the second most common neoplasm in hematology. Men are affected slightly more often than women (ratio 1.4:1). MM is now a non-curable disease, but appropriate therapies can reduce symptoms and stop disease progression. In asymptomatic MM (“smoldering” MM), no active therapy is given, but the patient is monitored (“watch and wait”). In symptomatic MM, treatment is indicated (Table 4) .

The most common symptoms are anemia (73%), bone lesions (66%), bone pain (58%), renal insufficiency (19%), and hypercalcemia (11%). Monoclonal proteins can be detected in 97% of patients.

In therapy, a distinction is made between three goals: Acute treatment to prevent life-threatening damage (e.g., plasmapheresis for hyperviscosity syndrome or dialysis for renal insufficiency), relief of symptoms and improvement of quality of life (e.g., radiotherapy for unstable fractures, bisphosphonates, analgesia), and reduction of symptoms and stopping progression (chemotherapy, stem cell transplantation). In recent years, the agents bortezomib (Velcade®) and lenalidomide (Revlimid®) have significantly improved the prognosis of patients with MM. In younger patients under 70 years of age, stem cell transplantation is an option, following induction therapy with bortezomib or lenalidomide followed by high-dose chemotherapy. Subsequently, two additional cycles of the initial treatment are given and, in patients with a high-risk profile, maintenance therapy is given for more than one year. In elderly patients, bortezomib- or lenalidomide-containing chemotherapy is given for at least 12-18 months – efficacy depends on duration of therapy.

Source: Medidays, Update Oncology, September 3, 2014, Zurich

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2014; 2(8): 32-34.