Vitiligo is an acquired pigment disorder which leads to a circumscribed loss of pigment due to destruction of the melanocytes. About 1% (0.5-2%) of the world’s population is affected by the disease. A comprehensive overview of the etiology, course, and treatment options for this complex disease.

Vitiligo is an acquired pigment disorder which leads to a circumscribed loss of pigment through destruction of the melanocytes of the skin, hair follicles and mucous membranes. Approximately 1% (0.5-2%) of the world’s population is affected by the disease, although the exact prevalence is not known (in India, for example, 8.8%). The onset of the disease occurs before the age of 30 in 70-80% of cases, before the age of 20 in 50%, and even in childhood in 35%. There are also case reports of onset in the third month of life, but the existence of true congenital cases is controversial. Segmental vitiligo usually begins earlier than non-segmental vitiligo and accounts for about 40% of cases in childhood. Men and women are equally affected by the disease, and no differences are known with regard to skin type and ethnologies [1–4].

Etiology/Pathogenesis

Vitiligo is a complex disease involving various mechanisms. Causative factors include biochemical, environmental, and immunological factors in genetically predisposed individuals [1]. There are several hypotheses that try to explain the destruction of melanocytes. Inflammation, autoimmunity, changes in redox status, and familial background are ostensibly attributed to (nonsegmental) vitiligo, whereas other pathogenetic concepts underlie the segmental variant [3].

Thus, in vitiligo, a genetic predisposition appears to play a role in its development. This was underlined, among others, by the identification of several vitiligo-associated genes. Familial clustering exists in 10-30% of cases [5].

The autoimmune hypothesis remains the most popular and is supported by association with other autoimmune diseases. Cytotoxic CD8+ cells and serum antibodies directed against specific melanocyte antigens, proinflammatory cytokines, and nonspecific immune defenses are involved in melanocyte demise [1,5].

Another theory involves a defective adaptation of melanocytes (and keratinocytes) to oxidative stress, which leads to autocytotoxic processes. Prooxidant environmental factors (e.g., radiation [including UV]), chemical agents (various phenols) lead to probable mitochondrial release of a reactive oxygen species (ROS). This induces premature cell aging with apoptosis. In addition, exposure to phenols causes defective folding of proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum. This leads to a complex cellular adaptation response (UPR), which also results in apoptosis. Both factors also cause the release of various proinflammatory cytokines, inducing an immune response [1].

It is further suggested that impaired cell adhesion between melanocytes and keratinocytes and structural changes in melanocytes may explain the predilection of vitiligo for mechanically stressed skin as well as the triggering of Köbner phenomenon [5].

The presence of a so-called melanocyte resevoir in the hair root sheath is also interesting. In the anagen phase, melanocytic stem cells in the bulge region have relative immune privilege and thus are not recognized by a cytotoxic autoimmune response. This could explain why hairs in vitiligo areas often remain pigmented or why repigmentation usually starts from the hair follicles [5].

The neuronal theory is most relevant to segmental vitiligo. It is thought that certain neurotransmitters (e.g., neuropeptide Y) may cause melanocyte destruction [5].

In segmental vitiligo, cutaneous mosaicism is also discussed as a cause, with some clinical overlap with cutaneous mosaic diseases such as segmental lentiginosis and epidermal nevus [5].

Possible triggers for triggering or worsening vitiligo include emotional stress as well as physical factors in terms of Köbner phenomena (e.g., severe sunburns, physical, chemical, or mechanical impact) [5].

An increased risk for the occurrence of vitiligo is shown by children with multiple halo nevi (Fig. 1) as well as patients under immunotherapy for metastatic melanoma, whereby this is considered a prognostically favorable sign with regard to melanoma [5].

Division

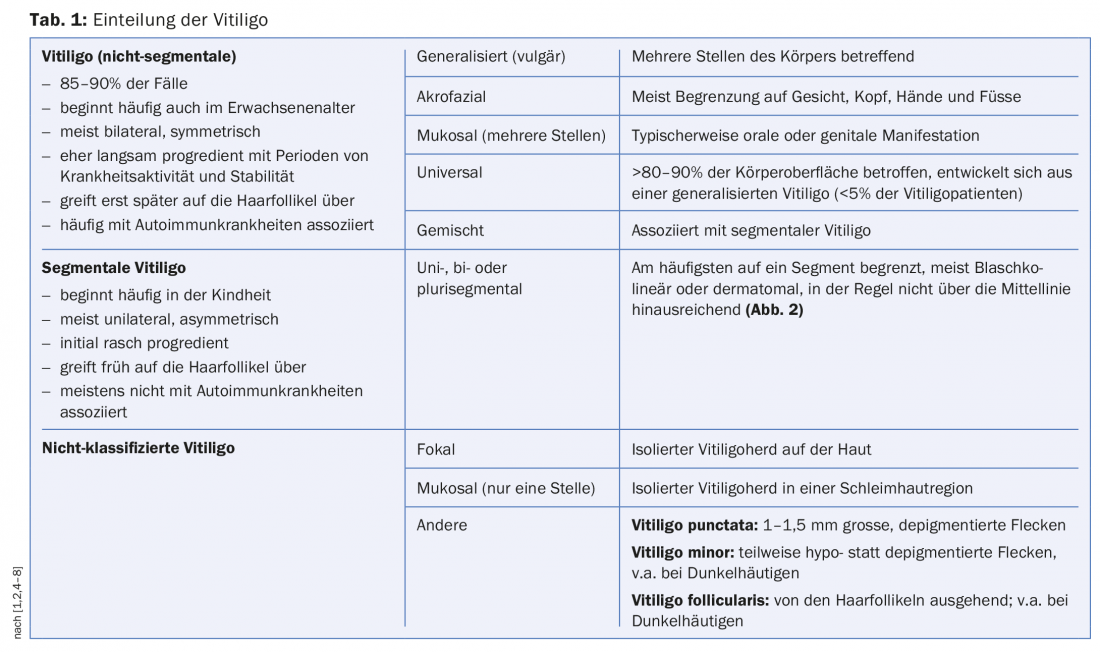

In 2012, the Vitiligo Global Issues Consensus Conference (VGICC) [6] revised the nomenclature. In this context, the term “non-segmental vitiligo” was abandoned in favor of the generic term “vitiligo.” Other subtypes of vitiligo include segmental vitiligo and unclassified vitiligo (Table 1) . Basically, all forms can start with a focal focus.

Clinic

The clinical picture is characterized by depigmented, small or large confluent, sharply and partly polycyclic limited, outwardly concave macules. Vitiligo (non-segmental) often begins in UV-exposed or mechanically stressed skin. The distribution is mostly bilateral and symmetrical. The predilection sites are face (perioral and periorbital region), neck, hands and feet, elbows and knees, axillae, groin, nipples and genitoanal region. Occasionally, depigmentation may be preceded by pruritus [3]. Within the vitiligo areas, white discoloration of the hair (e.g. poliosis of the eyelashes) may also occur. In addition, the mucous membranes (especially lips and oral mucosa) are occasionally affected [5].

In about 40% of patients, vitiligo is triggered by physical stimuli (e.g., sunburns, inflammation, and injury), the so-called Köbner phenomenon (Fig. 3) [5].

In vitiligo, there is an increased predisposition to the development of other autoimmune diseases in 15-25% of cases, the most common being autoimmune thyreopathy (of which Hashimoto’s disease in 88% and Graves’ disease in 12%) [5]. Other autoimmune diseases that are not always significantly more common include autoimmune gastritis, psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, pernicious anemia, Addison’s disease, alopecia areata, lupus erythematosus, type I diabetes, multiple sclerosis, atopic eczema, and autoimmune polyglandular endocrinopathy syndrome [5]. Segmental vitiligo is usually not associated with autoimmune diseases [8].

In addition, the disease is associated with worsened quality of life, depression, premature graying, halo nevi, subclinical hearing impairment (possibly. Disruption of melanocytes of the stria vascularis of the cochlea), ophthalmogic symptoms (night blindness, photophobia), Vogt-Koynagi-Harada syndrome (vitiligo with meningoencephalitis, neurological symptoms, uveitis, dysacusis), and the rare Alezzandrini syndrome (unilateral asymmetric vitiligo of the face with poliosis, retinal degeneration, and deafness). [2,5].

According to a recent study [9] of over 10,000 vitiligo patients, there appears to be no increased risk of melanocytic and nonmelanocytic skin cancer.

Diagnosis

In addition to the general history, it is useful to elicit the impairment of quality of life. This can be quantified, for example, using the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) [10].

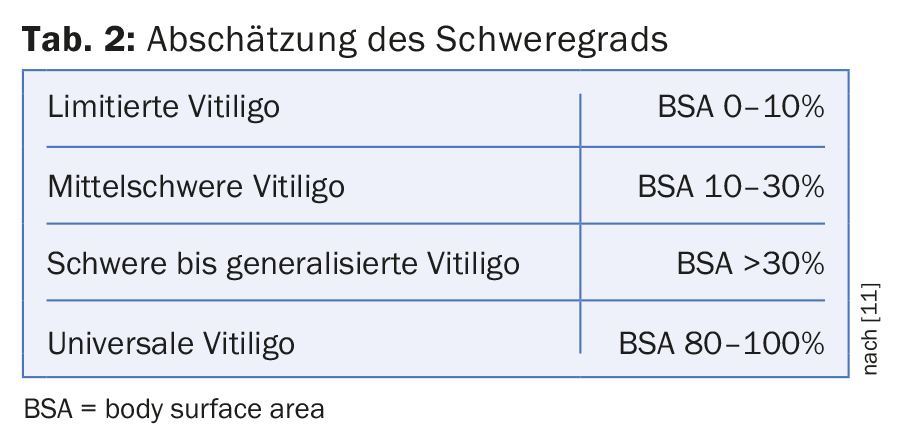

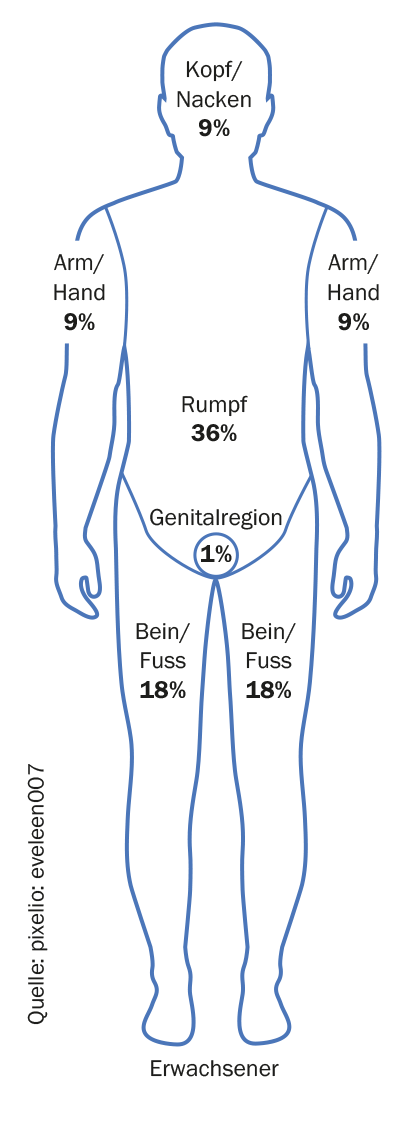

In the course of the whole-body examination (including mucous membranes), the extent of the infestation can be estimated. Vitiligo foci can often be better demarked under Wood’s light [5]. Scoring systems such as the Vitiligo Area Scoring Index (VASI) or the Vitiligo European Task Force Assessment (VETFa) can be used to assess expression or activity [11]. However, these are not very practical in clinical practice, so that a modified VETFa (determination of the BSA [“Body Surface Area”]) can be used to estimate the severity (Table 2) [10]. The rule of nine (see graphic) is used, whereby the palm (including fingers) of a patient comprises approx. 1% of the body surface. It should be noted that certain areas of the body (face, hands, mammae and genitals) are generally associated with greater distress. For activity assessment, the categories “progressive”, “stable” (>6 months) and “regressive” can be used in a simplified way [11].

Clinical signs of vitiligo foci activity are considered to be convex borders, sometimes with a mild inflammatory aspect and itching [2]. Spontaneous or therapy-induced retreating vitiligo foci can be detected by (peri-)follicular and confetti-like repigmentation as well as by their often blurred borders (Fig. 4 ) [5].

The determination of thyroid function or the corresponding autoantibodies (TSH, anti-TPO and antithyroglobulin antibodies) is recommended as basic laboratory diagnostics. Additional autoantibodies may be useful in conjunction with personal and family history and depending on pathologic laboratory parameters. If thyroid autoantibodies are positive, an endocrinology consult may also be evaluated with the question of autoimmune polyglandular endocrinopathy syndrome [12].

Biopsy should not be performed routinely, but may be performed, especially if focal vitiligo is suspected. Histologically, there are often absent to only single melanocytes while follicular melanocytes are present in the marginal area. A lymphocytic infiltrate is usually found in the periphery of active foci [2].

Differential diagnoses

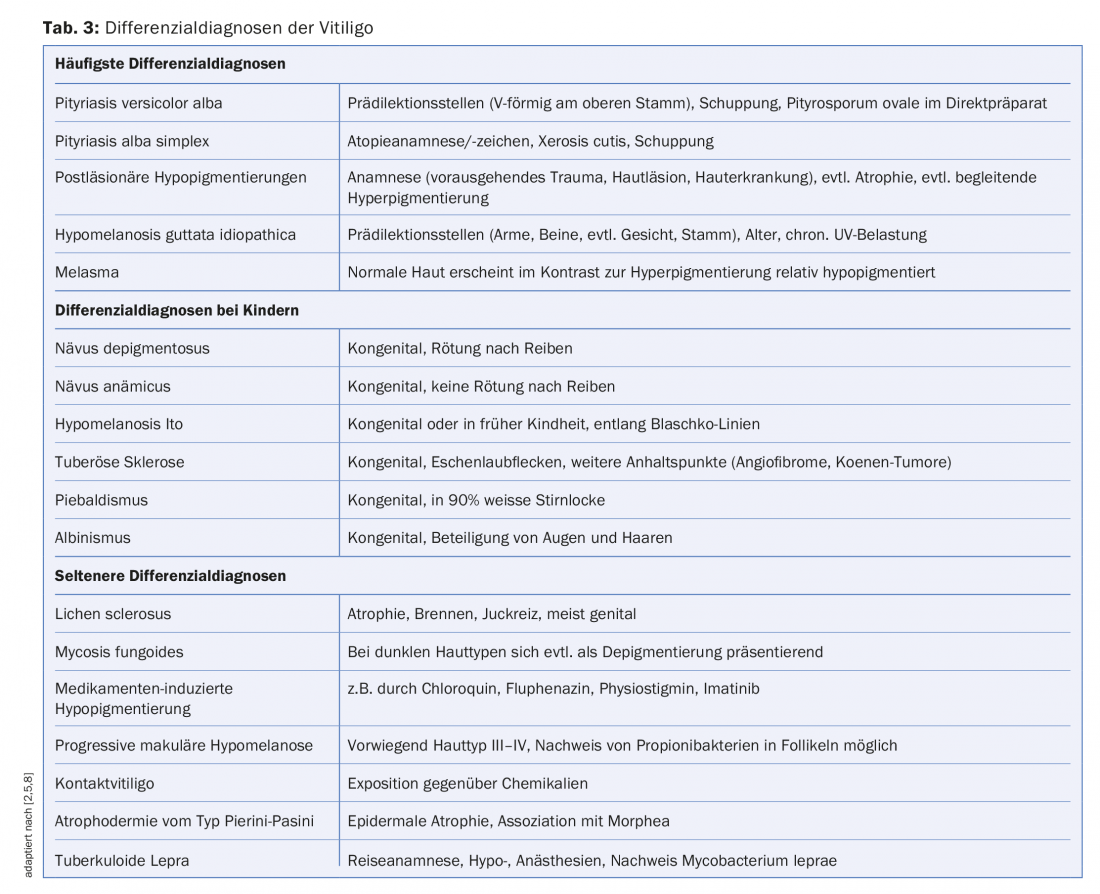

Other diseases leading to hypo- and depigmentation may mask vitiligo and should be excluded (Tab. 3). This is especially true for the diagnosis of focal vitiligo forms [1].

Therapy

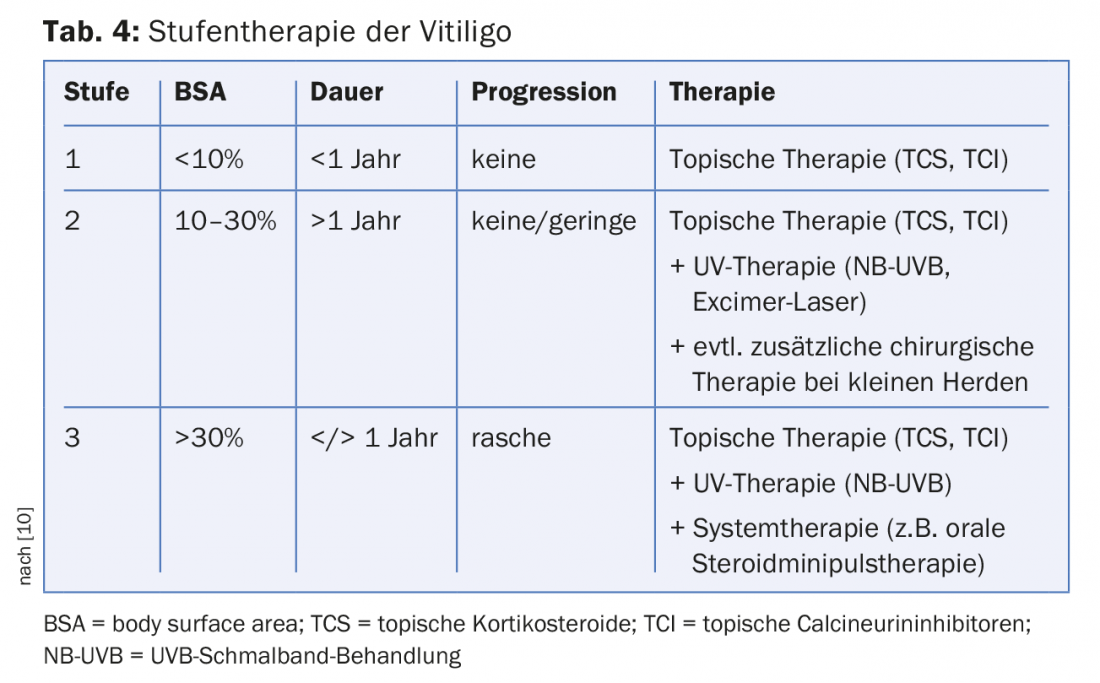

The therapy should be adapted to the individual suffering of the patient, because up to now no curative and permanent repigmentation is possible [10]. However, satisfactory partial success can often be achieved, with the best results expected in the face, followed by the trunk and extremities [2]. The acras usually show only a slight response to treatment. The goals of therapy are to stop the disease process, to achieve a cosmetically flawless skin appearance and to reduce the psychological suffering. It is recommended to adjust the treatment to the extent, duration and activity of vitiligo. Recently, a review [10] described the stepwise therapy for initial therapy seen in Table 4. Recurrences are usually treated as in the second or third stage. Since the response of segmental vitiligo to topical treatments is usually rather poor, it is recommended to proceed according to the second stage.

General measures [12]: In general, avoidance of physical stimuli, sun protection measures (reduction of contrast), camouflage, permanent make-up, self-tanning products and, due to the often great, occasionally also culturally related suffering, psychological co-care should be mentioned.

Topical corticosteroids (TCS) [10,12]: In the eyelid area or on the face, TCS of drug classes I-II (e.g. hydrocortisone, prednicarbate) can be used for three to a maximum of six weeks. For extrafacial vitiligo, 1-times-daily use of potent TCS of drug classes III-IV (e.g., mometasone fuorate, clobetasol propionate) for a maximum of three months or as interval therapy (once daily for 15 days/month) for a maximum of six months is recommended. Local skin side effects such as skin atrophy, telangiectasia, hypertrichosis, acneiform lesions, and striae should be noted.

Topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCI) [10]: Vitiligo lesions on the face in particular can be treated effectively with TCI (tacrolimus, pimecrolimus) with fewer side effects. Extrafacial lesions usually respond worse to TCI. The application, which is an off-label indication, should be twice daily for six months; in addition, mild sun exposure may be recommended. In case of improvement, the preparation should be used for a longer period of time (e.g. >1 year). Common side effects may include burning, itching, and redness.

UV therapies [2,7,10,12]: Whole- or partial-body narrow-band UVB (NB-UVB, 311 nm) is the treatment of choice for active or extensive vitiligo, as it appears to be more effective than other UV therapies. It has an immunosuppressive effect as well as a direct effect on melanocyte proliferation. Primarily, exposure can be performed two to three times a week for 3-6 months; if successful (>25% repigmentation), treatment can be performed as long as progressive repigmentation is evident or for a maximum of 1-2 years (for skin type I-III max. 200 therapy sessions). Accompanying local therapy with TCS or TCI can be performed on the days without radiation (Fig. 4). Side effects are usually limited to dose-dependent erythema. A potential risk for non-melanocytic skin cancer has not been described with UVB narrowband treatment, but cannot be excluded with absolute certainty. UV treatment is not recommended for children.

For localized vitiligo foci, excimer laser treatment (UVB 308 nm) is an option, with good results reported especially for segmental vitiligo. Other UV therapies (e.g. PUVA) have rather less importance in vitiligo treatment.

Systemic Steroids [10,12]: In cases of extensive vitiligo, rapid progression and insufficient response to UV therapy, the implementation of oral steroid minipulse therapy for 3-6 months may be considered (e.g., dexamethasone 4 mg p.o. on two consecutive days of the week). This may stop disease activity, but induction of repigmentation is unlikely. Side effects may include weight gain, sleep disturbances, agitation, acne, menstrual irregularities, and hypertrichosis. At the same time or subsequently, the implementation of a UVB narrowband treatment may make sense.

Surgical therapies [4,10,12,13]: The goal of surgical interventions is to replace melanocytes in vitiligo areas with those from normally pigmented autologous skin. This possibility can be evaluated especially in segmental vitiligo (e.g., leukotrichia due to lack of melanocyte reservoir) and in circumscribed vitiligo forms stable for more than one year. Different methods are known, such as the introduction of donor melanocytes or stem cells via “punchgrafting”, “microneedling”, suction bladders and from in vitro cultures. Often surgical therapies are combined with another treatment (e.g. UV therapy).

Other or experimental therapies [10,12]: Regarding other topical therapies (e.g., prostaglandin E2 [Melanozytenwachstumsfaktor], melagenin [Extrakt der menschlichen Plazenta], topical phenylalanine, topical L-dopa, tar, anacarcin forte, topical minoxidil), there are few conclusive studies. Possibly, their effect is based on an increase in light sensitivity.

Topical or systemic antioxidants (e.g., pseudocatalase, vitamin C, vitamin E, coenzyme Q10, lipoic acid, Polypodium leucotomos, catalase/superoxide dismutase, Ginkgo biloba) are used singly or in combination, often accompanied by UV therapy. However, clear evidence of efficacy is lacking and studies are limited.

In combination with UVB narrowband treatment, the α-MSH analog afamelanotide was studied, and the combination treatment was superior to UV therapy alone.

For contraindications to oral steroid minipulse therapy, methotrexate can be evaluated, which was found to be equally effective at a low dose of 10 mg p.o. in a study [14]. Other immunosuppressive drugs (e.g., cyclophosphamide, ciclosporin, azathioprine) and biologics (e.g., TNF-α blockers) have been less well studied and their use is not recommended in practice. Possibly oral Janus kinase inhibitors represent a future therapeutic option for vitiligo, in a recent casuistry [15] significant repigmentation under treatment with tofacitinib was reported.

The indication for depigmentation treatment (hydroquinone derivatives) of pigmented residual foci arises only in universal vitiligo and should be given with great caution.

Forecast

The course of vitiligo is basically unpredictable, but there are some factors that worsen the prognosis. This includes an onset of the disease at a young age (childhood), a longer duration of the disease (>3-5 years) and a large area of the skin surface affected (>30% BSA). Progression or concomitant symptoms such as Köbner’s phenomenon and leukotrichia are also considered prognosis-deteriorating factors [10].

Spontaneous partial repigmentation may occur in approximately 20% of cases in vitiligo [4]. Repigmentation rates of 40-100% have been reported under UVB narrowband treatment, depending on the location of the lesions [7]. However, recurrence can be expected in approximately 30-40% of cases within one year [10].

Prophylaxis

Topical calcineurin inhibitors can be used for recurrence prophylaxis after repigmentation. A recent study [16] has confirmed the effectiveness of twice-weekly use of tacrolimus 0.1%.

Take-Home Messages

- Vitiligo is a multifactorial and polygenetic condition that results in circumscribed depigmentation due to the destruction of melanocytes.

- The etiological basis of (non-segmental) vitiligo is assumed to be autoimmune pathogenesis in combination with maladaptation of melanocytes to oxidative stress in the presence of genetic predisposition. In the segmental variant, a neuronal cause as well as a genetic mosaic seem to play a role.

- If there is an increased tendency for autoimmune diseases, a corresponding thyreopathy should be excluded by laboratory tests.

- The therapy should be adapted to the individual suffering and be appropriate to the stage. The efficacy of monotherapy is usually limited to the face, so that UVB narrowband treatment is often required in addition at other sites.

- Because recurrence is common after successful repigmentation, prophylactic topical calcineurin inhibitors may be used.

Literature:

- Boniface K, et al: Vitiligo: Focus on Clinical Aspects, Immunopathogenesis, and Therapy. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2018; 54(1): 52-67.

- Hartmann A: Vitiligo: diagnosis, differential diagnosis and current therapy recommendations. Dermatologist 2009; 60: 505-515.

- Ezzedine K, et al: Multivariate analysis of factors associated with early-onset segmental and nonsegmental vitiligo: a prospective observational study of 213 patients. Br J Dermatol 2011; 165: 44-49.

- Park JH, et al: Clinical Course of Segmental Vitiligo: A Retrospective Study of Eighty-Seven Patients. Ann Dermatol 2014; 26: 61-65.

- Schild M, et al: Vitiligo – clinic and pathogenesis. Dermatologist 2016; 67: 173-188.

- Ezzedine K, et al: Revised classification/nomenclature of vitiligo and related issues: the Vitiligo Global Issues Consensus Conference. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res 2012; 25(3): E1-13.

- Rodrigues M, et al: Current and emerging treatments for vitiligo. J Am Acad Dermatol 2017; 77: 17-29.

- Taïeb A, et al: Vitiligo. N Engl J Med 2009; 360: 160-169.

- Paradisi A, et al: Markedly reduced incidence of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer in a nonconcurrent cohort of 10,040 patients with vitiligo. J Am Acad Dermatol 2014; 71: 1110-1116.

- Meurer M, et al: Therapy of vitiligo. Dermatologist 2016: 249-264.

- Taïeb A, Picardo M; VETF Members: The definition and assessment of vitiligo: a consensus report of the Vitiligo European Task Force. Pigment Cell Res 2007; 20(1): 27-35.

- Taïeb A, et al: Guidelines for the management of vitiligo: the European Dermatology Forum consensus. BJD 2013; 168: 5-19.

- Ezzadine K, et al: Vitiligo. Lancet 2015; 386: 74-84.

- Singh H, et al: A randomized comparative study of oral corticosteroid minipulse and low-dose oral methotrexate in the treatment of unstable vitiligo. Dermatology 2015; 231(3): 286-290.

- Craiglow BG, et al: Tofacitinib Citrate for the Treatment of Vitiligo: A Pathogenesis-Directed Therapy. JAMA 2015; 151: 1110-1112.

- Cavalié M, et al: Maintenance therapy of adult vitiligo with 0.1% tacrolimus ointment: a randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled study. J Invest Dermatol 2015; 135: 970-974.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2018; 28(2): 10-16

DERMATOLOGY PRACTICE 2020; 28(3): 8-13