The novel CGRP receptor antibody erenumab could usher in a new era in migraine therapy. Initial results from Phase II studies are encouraging.

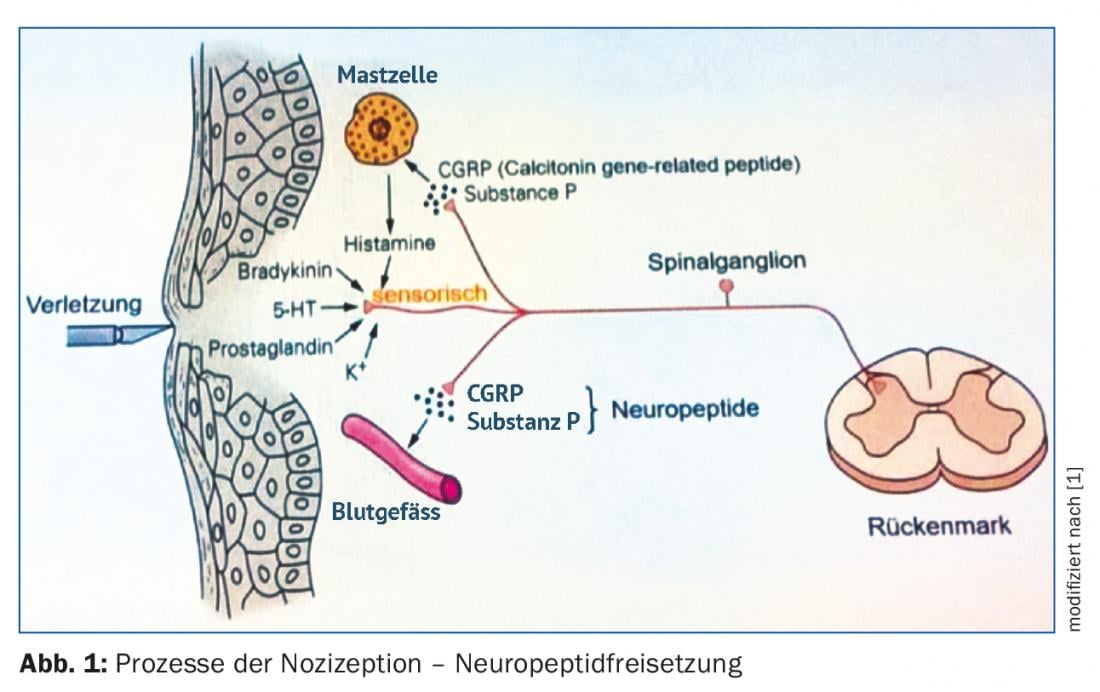

The “calcitonin gene-related peptide” (CGRP) plays an important role in the development of headache disorders, probably because it functions primarily as a potent vasodilator and neuromodulator. Although CGRP has already been shown in studies to be associated with headache and migraine, its exact origin and underlying mechanism of action are not yet conclusively understood.

A possible relationship between CGRP, as a component of the trigeminovascular system, and headache disorders has been intensively discussed since 1988. Based on this assumption, the first CGRP antagonists were developed, which should find their application especially in acute pain therapy. However, the use of these small peptides led to an increase in serious liver problems, which ultimately meant the end of CGRP antagonists in a potential migraine therapy.

The CGRP receptor in the brain

CGRP is actually a splice variant of the calcitonin gene, which gives rise to a small neuropeptide that is involved in processes including nociception. CGRP is produced and released primarily as a result of pain stimuli (Fig. 1). It causes very effective vasodilation of vessels, which makes it partly responsible for the frequently occurring pain erythema. However, the original task of CGRP-mediated vasodilation is quite different: The primary aim is to initiate repair of possible damage that causally triggered the pain stimulus.

Further studies also showed that CGRP was elevated, for example, in the jugular venous plasma of migraine patients. Very likely, the peptide also played a role in the respective pain symptomatology. The source of the peptide within the brain, however, remained unclear.

The peptide CGRP has been detected immunohistochemically in brain structures such as the dura mater, trigeminal ganglion, and medulla oblongata. Its partner, the CGRP receptor, has also been shown to be found in these brain sections. However, the receptor is only formed in those nerve cells that do not themselves produce and release the ligand, CGRP. In addition, the CGRP receptor is found in arterial vessels of the dura mater and in mononuclear cells of the immune system.

After binding of the ligand to its receptor, the receptor is activated, which in turn leads to an intracellular increase in cAMP concentration, a major effector of signal transduction in cells. This process was successfully prevented experimentally both by blocking the ligand CGRP and by inhibiting the CGRP receptor.

Conclusion: CGRP and its receptor are found in brain areas that are thought to be partly responsible for the development of headache disorders and migraine. In addition, both can be specifically inhibited and thus subsequent reactions can be stopped. Both together made CGRP an interesting candidate for the development of potential antibody therapies in migraine prophylaxis.

Current data from phase II studies

Initial study results on the CGRP receptor antibody erenumab are indeed quite promising, such as data from a phase II study of 483 patients with episodic migraine who were divided into four treatment arms and received either placebo or the antibody (doses: 7 mg, 21 mg, and 70 mg, respectively). CGRP receptor antibody was administered subcutaneously every four weeks for a period of three months [2].

Only at the dose of 70 mg did erenumab have a significant effect compared to placebo – at weeks 9-12, the number of migraine days decreased by 3.4 days vs. 2.3 days in the verum group compared to baseline (p=0.021) [2]. The 50% responder rate was also higher in the verum group (46%) than with placebo (30%) [1]. Adverse side effects occurred in about half of the patients in both groups in this study, mainly in the form of nasopharyngitis, fatigue, and headache [2].

Just as for episodic migraine, erenumab may be helpful for patients with chronic migraine. In a phase II trial (AMG 344) with 667 participants, they received either 70 mg or 140 mg of the antibody or an equivalent placebo preparation subcutaneously every four weeks for three months [2]. The primary endpoint of the study was the change in the number of migraine days per month within treatment weeks 8-12 compared with baseline. Both antibody groups (70 mg, 140 mg), compared with the placebo group, achieved a reduction in headache days of 6.6 days per month vs. 4.2 days on placebo (Fig. 2) [3].

In addition, the result in patients with excessive use of medication for migraine is particularly interesting: In the study (AMG 344), these patients apparently benefited from prophylactic antibody therapy – and this even without prior detoxification [3].

Cardiovascular safety of antibody therapy.

Since CGRP receptors are found in very many tissues and organs of the body, in addition to the nervous system, for example, also in the heart, concerns arose very early that inhibition of CGRP signaling to the heart in CHD patients might block cardioprotection in acute ischemia (myocardial infarction) [4]. However, this could not be shown in animal studies so far; on the contrary, no effect on heart rate or arterial blood pressure was found previously, e.g. in healthy rats [5]. Thus, at present, subcutaneous antibody therapy for migraine is thought to carry only a small acute cardiovascular risk-but the long-term effects of CGRP blockade, as well as the protective mechanisms possibly mediated by CGRP, need to be further investigated in the future.

Antibodies versus established migraine therapies.

A major problem in headache prophylaxis – which is why new forms of therapy are currently urgently needed – is poor patient compliance. While up to 66% of patients still follow the treatment plan when taking the prophylactic medication once a day, this figure is significantly lower at only 30% when taking it several times a day. Nearly one in five patients also discontinues prophylaxis prematurely due to substance-related side effects. All this ultimately leads to the fact that nowadays every fourth to every second migraine patient (25-50%) discontinues prophylaxis before reaching the planned duration or dosage. Less than 25% of patients take oral migraine prophylaxis for more than one year. In the second and third prophylaxis, adherence after six months is even only about 16% [6–9].

In contrast, the new therapeutic approach using CGRP receptor monoclonal antibodies, such as erenumab, may offer the following advantages over conventional migraine therapy:

- Higher specificity

- s.c./i.v. application, thus eliminating the need for tablets, which could increase therapy adherence

- Fewer side effects

- Immediate onset of action

- Dosage titration is not required.

Conclusion for practice

Many headache or migraine patients are not adequately treated with the currently available medication. Side effects and a mostly resulting lack of therapy adherence favor this. Therefore, the call for new therapeutic approaches that have fewer side effects and are more specifically effective is becoming louder and louder.

Since CGRP plays a very large role in the pathophysiology of primary headache, CGRP receptor antibodies could play a key role in the therapy of both episodic and chronic migraine in the future. Initial clinical data from phase II trials support the efficacy of antibody therapy based on a significant reduction in migraine days per month. Thus, CGRP receptor antibodies may indeed become a promising therapeutic option for migraine patients in the near future.

Source: IS07 “Monoclonal antibodies against CGRP – for migraine-specific prophylaxis” (Organizer: Novartis), German Pain Congress 2017, October 13, 2017,

Mannheim (D)

Literature:

- Kandel ER, et al: Principles of Neural Science; 2000; 4th edition, New York: Mcgraw-Hill Professional.

- Sun H, et al: Lancet Neurol 2016; 15(4): 382-390.

- Tepper S, et al: Lancet Neurol 2017; 16(6): 425-434.

- MaassenVanDenBrink A, et al: Trends Pharmacol Sci 2016; 37(9): 779-788.

- Zeller J, et al: Br J Pharmacol 2008; 155(7): 1093-1103.

- Evans & Linde: Headache 2009; 49: 1054-1058.

- Gracia-Naya, et al: Rev Neurol 2011; 53: 201-208.

- Hepp, et al: Cephalagia 2015; 35: 478-488.

- Mulleners, et al: Cephalalgia 1998; 18: 52-56.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2017; 12(11): 36-38