Despite the known demographic trends, we currently know too little with regard to old or even very old patients whether and how we can adapt and individualize radiotherapy (RT), especially if it is part of a multimodal therapy concept. Screening such as the G8 may be useful to detect early the increased “vulnerability” of an elderly patient. Interdisciplinary cooperation and close involvement of the patient and his family in the decision-making processes are the basis for viable therapy concepts. New technical developments in radio-oncology open up very good options, especially for the patient group of the elderly and with relevant comorbidities, so that curative approaches can also be pursued.

The phenomenon of an aging population is observed in all developed countries: In Switzerland, average life expectancy increased by 5.1 years to 85.2 years for women and by as much as 7.6 years to 81.0 years for men between 1984 and 2014. Since for very many tumor entities the incidence of disease increases with age, we must expect to see a higher absolute number of cancer cases in the future. In the United States, the number of cancer cases is expected to increase by 45% between 2010 and 2030, and this increase will be almost exclusively in the age group >65 years [1]. There are differences between the sexes: For men, the rate of disease in the designated age group in Switzerland is described to be almost twice as high as for women, whereas it is exactly the opposite for <55-year-old patients [2].

Are assessments useful?

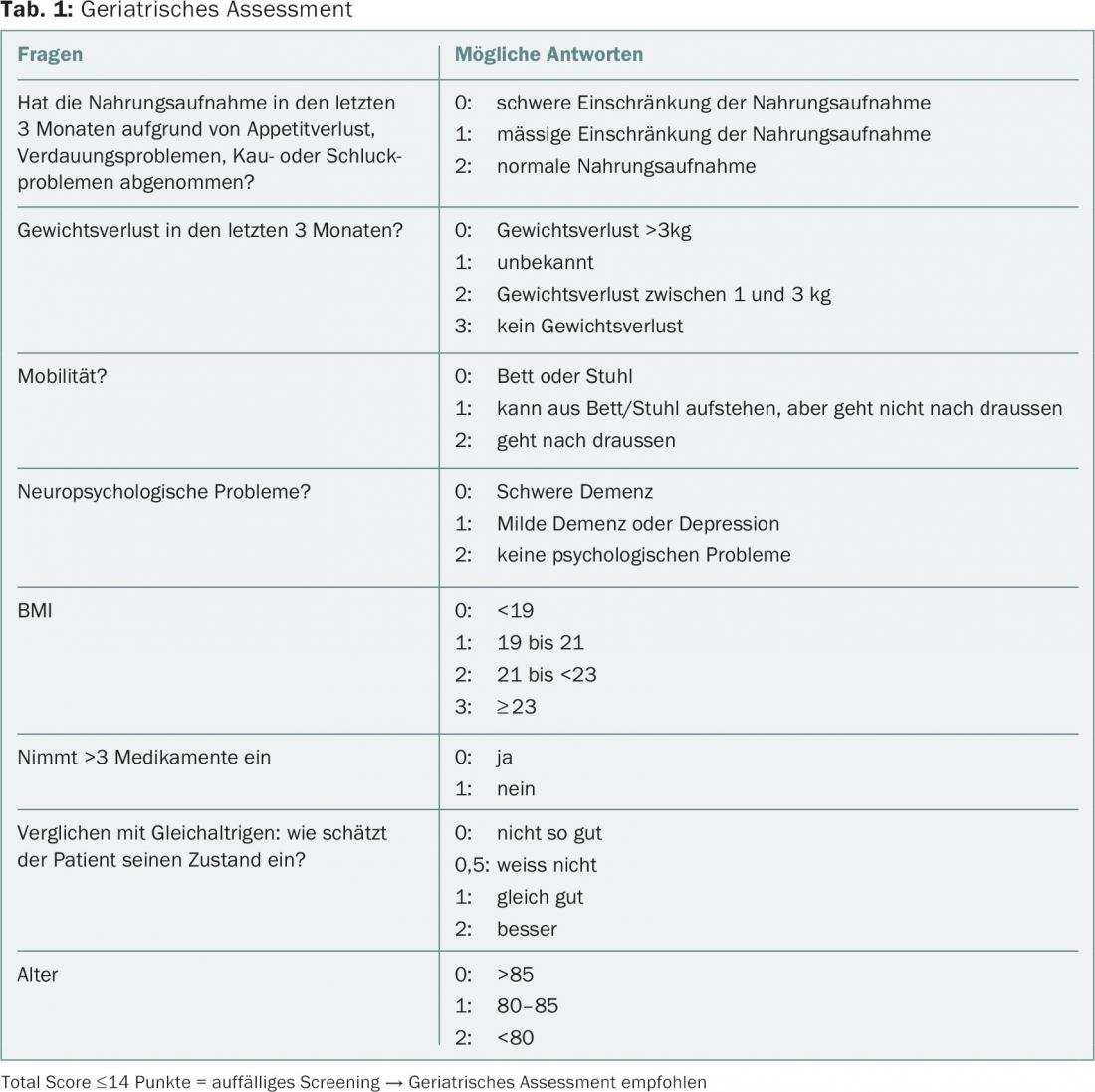

The question of when a patient is an elderly patient has not yet been defined in a binding manner. Geriatricians generally choose the age limit of 70 years because it is assumed that people of this age are likely to have increased vulnerability on average. However, we know that a person’s biological age can differ significantly from his or her chronological age. A study last year showed a variance in biological age from 28 to 61 years in 38-year-olds [3]. It is therefore often not easy to decide whether an “older” patient can be assumed to have an individually increased risk of relevant side effects due to oncological therapy. Geriatric assessments can help to collect objective and relevant parameters on function and cognition, but are time-consuming and therefore unsuitable for non-specific use in clinical practice in all patients of a defined age group. The International Society of Geriatric Oncology (SIOG) therefore recommends the use of screening tools that can indicate whether a patient might benefit from a detailed assessment, in addition to recording performance status and co-morbidities. Because of its high sensitivity for detecting “frailty,” the G8 (Table 1) is given a slightly higher priority than other brief assessments [4].

What about the evidence?

Another problem with regard to treatment decisions in elderly patients is the lack of evidence, because studies usually systematically exclude these patients. A 2015 study showed that 47% of all patients at a Seattle radiation oncology clinic had treatment decisions made without level I evidence based on randomized trials [5]. Direct applicability of study results generated in younger populations to an older patient population is not immediately possible for many reasons. For numerous tumor entities it has been shown that patient age and concomitant comorbidity have an impact on: 1) the survival prognosis as well as the natural history of the disease; 2) the tolerability of radiotherapy or multimodality treatment in terms of quality of life, morbidity, and mortality; 3) the efficacy of radiotherapy and multimodality therapy related to survival and freedom from recurrence; 4) the indication of us oncologists and radio-oncologists [9 –11]. The following is an example of how age factors into current clinical decisions for the four most common tumor diseases.

Breast Cancer

In breast carcinoma, radiotherapy of the residual breast including local tumor bed saturation (boost) significantly reduces the local recurrence rate regardless of age; however, the absolute local recurrence risk also decreases with increasing age. Therefore, with increasing age and favorable tumor prognostic parameters (e.g., tumor size, grading), the impact of local control and thus local radiotherapy on survival becomes smaller. Therefore, irradiation should be critically evaluated in older patients without tumor-specific risk factors and concomitant relevant concomitant diseases. Radiation should be hypo-fractionated in only 20 treatment sessions instead of 25. Similarly, tumor bed resaturation can be omitted in older patients without risk factors. Another approach could be partial breast irradiation in this high-risk group; however, long-term results on this question are still pending [12].

Prostate Cancer

Elderly patients with moderate to severe comorbidity very rarely die from prostate cancer when it is detected without risk factors (high PSA value, high Gleason score, capsular overgrowth) [13]. In this case, an “active surveillance” strategy makes sense. On the other hand, elderly patients with little comorbidity and an intermediate or high-risk tumor stage benefit from radiotherapy in combination with short-term hormonal therapy (HT). In severe comorbidity, the benefit from HT in the intermediate- and high-risk groups disappears [14].

Bronchus carcinoma

In elderly patients with locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer, RT has a high value because these patients are often inoperable. Simultaneous radiotherapy and chemotherapy improves overall survival but is associated with significantly increased acute toxicity. In select patients, RT can still be combined with low-dose concomitant chemotherapy [15]. In a Japanese study, life expectancy was significantly improved by combined treatment, without increased treatment-related mortality.

Rectal Cancer

In rectal cancer, preoperative radiotherapy improves locoregional recurrence rates regardless of tumor stage and also age. Thus, in elderly patients in very good performance status, multimodal therapy should not be abandoned without good reason [16]. However, if relevant comorbidities are present, a differentiated approach should be adopted, which may well allow rectal resection to be omitted in cases of clinically complete remission after radio(chemo)therapy on MRI and rectoscopy. In the clinic, combined radiochemotherapy (45-50 Gy in 1.8 Gy fractions combined with capecitabine p.o.) or, alternatively, the short regimen consisting of 5 sessions of 5 Gy each is used for locally advanced tumors and should be preferred in the elderly patient for the same oncologic outcome and comparable quality of life [17].

Place of precision radiotherapy in the elderly patient.

Today, technical and methodological developments in radio-oncology make it possible to focus the radiation dose on the tumor while sparing the surrounding normal tissue. Stereotactic radiation therapy in the body stem region (SBRT) bundles this technical progress and enables highly precise tumoricidal radiation within a few treatment sessions. Such therapy is particularly suitable for elderly patients due to its favorable toxicity profile, lack of invasiveness, and brief outpatient therapy.

In stage I NSCLC, SBRT already has a firm place in international guidelines (ESMO, NCCN) when surgical flap resection is not safely possible due to age and comorbidities. SBRT can be used safely and effectively even in patients aged >80 years: In >300 patients with median age of 79-85 years, not a single SBRT-induced grade V toxicity has occurred and grade III-IV toxicities have been observed in <3% of patients. Very good tolerability combined with high local tumor control have led to a significant improvement in the prognosis of these patients by SBRT despite old age or comorbidities [18]. In a recently highly published analysis of two phase III trials, SBRT was established as a possible alternative to surgery even in the operable setting. It is also essential that these excellent results of SBRT could be confirmed outside of prospective studies in German-speaking countries in 582 patients [19].

Even though such high evidence is so far only available for early-stage NSCLC, this experience may well be extrapolated if local therapy is generally indicated based on the oncologic evaluation. In the context of so-called oligometastasis, SBRT represents a gentle, noninvasive, and locally highly effective therapy that has been successfully used for lung, liver, adrenal, and lymph node metastases [20]. Further indications such as primary stereotactic irradiation of prostate carcinoma, primary liver tumors and small renal cell carcinomas in cases of inoperability are currently being scientifically evaluated.

Literature:

- Smith BD, et al: Future of cancer incidence in the United States: burdens upon an aging, changing nation. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27(17): 2758-2765.

- Federal Statistical Office (FSO), National Institute of Cancer Epidemiology and Registration (NICER), Swiss Childhood Cancer Registry (SCRC). Swiss Cancer Report 2015. Status and developments. Neuchâtel 2016.

- Belsky DW, et al: Quantification of biological aging in young adults. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2015; 112 (30): E4104-E4110.

- Decoster L, et al: Screening tools for multidimensional health problems warranting a geriatric assessment in older cancer patients: an update on SIOG recommendations. Ann Oncol 2015; 26: 288-300.

- Apisarnthanarax S, et al: Applicability of randomized trials in radiation oncology to standard clinical practice. Cancer 2013; 119(16): 3092-3099.

- Poortmans PM, et al: Internal Mammary and Medial Supraclavicular Irradiation in Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med 2015; 373(4): 317-327.

- Whelan TJ, et al: Regional Nodal Irradiation in Early-Stage Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med 2015; 373(4): 307-316.

- Bradley JD, et al: Standard-dose versus high-dose conformal radiotherapy with concurrent and consolidation carboplatin plus paclitaxel with or without cetuximab for patients with stage IIIA or IIIB non-small-cell lung cancer (RTOG 0617): a randomised, two-by-two factorial phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol 2015; 16(2): 187-199.

- Elomrani F, et al: Management of early breast cancer in older women: from screening to treatment. Breast Cancer (Dove Med Press) 2015; 7: 165-171.

- Blanco R, et al: A review of the management of elderly patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol 2015; 26(3): 451-463.

- Droz JP, et al: Management of prostate cancer in older patients: updated recommendations of a working group of the International Society of Geriatric Oncology. The lancet oncology 2014; 15(9): e404-414.

- Vaidya JS, et al: Risk-adapted targeted intraoperative radiotherapy versus whole-breast radiotherapy for breast cancer: 5-year results for local control and overall survival from the TARGIT-A randomised trial. Lancet 2014; 383(9917): 603-613.

- Daskivich TJ, et al: Overtreatment of men with low-risk prostate cancer and significant comorbidity. Cancer 2011; 117(10): 2058-2066.

- Nguyen PL, et al: Radiation with or without 6 months of androgen suppression therapy in intermediate- and high-risk clinically localized prostate cancer: a postrandomization analysis by risk group. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2010; 77(4): 1046-1052.

- Atagi S, et al: Thoracic radiotherapy with or without daily low-dose carboplatin in elderly patients with non-small-cell lung cancer: a randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial by the Japan Clinical Oncology Group (JCOG0301). Lancet Oncol 2012; 13(7): 671-678.

- Bhangu A, et al: Survival outcome of operated and non-operated elderly patients with rectal cancer: A Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results analysis. European journal of surgical oncology : the journal of the European Society of Surgical Oncology and the British Association of Surgical Oncology 2014; 40(11): 1510-1516.

- Guckenberger M, et al: Comparison of preoperative short-course radiotherapy and long-course radiochemotherapy for locally advanced rectal cancer. Radiotherapy and oncology : organ of the German Radiological Society [et al] 2012; 188(7): 551-557.

- Haasbeek CJ, et al: Early-stage lung cancer in elderly patients: A population-based study of changes in treatment patterns and survival in the Netherlands. Ann Oncol 2012; 23(10): 2743-2747.

- Guckenberger M, et al: Safety and efficacy of stereotactic body radiotherapy for stage i non-small-cell lung cancer in routine clinical practice: a patterns-of-care and outcome analysis. J Thorac Oncol 2013; 8(8): 1050-1058.

- Widder J, et al: Pulmonary oligometastases: metastasectomy or stereotactic ablative radiotherapy? Radiother Oncol 2013; 107(3): 409-413.

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2016; 4(7-8): 6-10.