At the KHM Congress in Lucerne, Prof. Gregor Hasler, MD, University Hospital of Psychiatry Bern, led an interesting workshop on “Cognition in Depression”. Memory problems, reduced concentration and slowing down are symptoms that both doctors and patients pay little attention to in depression – even though they massively restrict the quality of life and ability to work.

Cognitive impairment in depression can occur in four subdomains of cognition: memory, attention, processing speed, and executive functions. Typical problems that patients describe are difficulty concentrating, impaired attention and difficulty focusing, problems with “multitasking,” poor short-term memory, slowing down, and also difficulty tackling and completing tasks. Both “hot” and “cold” cognition are disturbed. Hot cognition is thinking under strong emotional involvement, e.g., an argument with the boss; cold cognition is thinking under low emotional involvement, e.g., watching a TV movie or making a shopping list.

Persistent symptoms with severe limitation of quality of life

Cognitive symptoms are often forgotten in the workup and treatment of depression, by both physicians and patients. In routine clinical assessment of depression, questions are traditionally asked only about the three complexes of emotional symptoms, physical symptoms, and additional symptoms (irritability, pain, tearfulness, anxiety, exaggerated fears about physical health). Cognition is also rarely an issue in classic depression questionnaires and scales. Patients, in turn, often do not perceive the concentration and memory impairment as part of the disease.

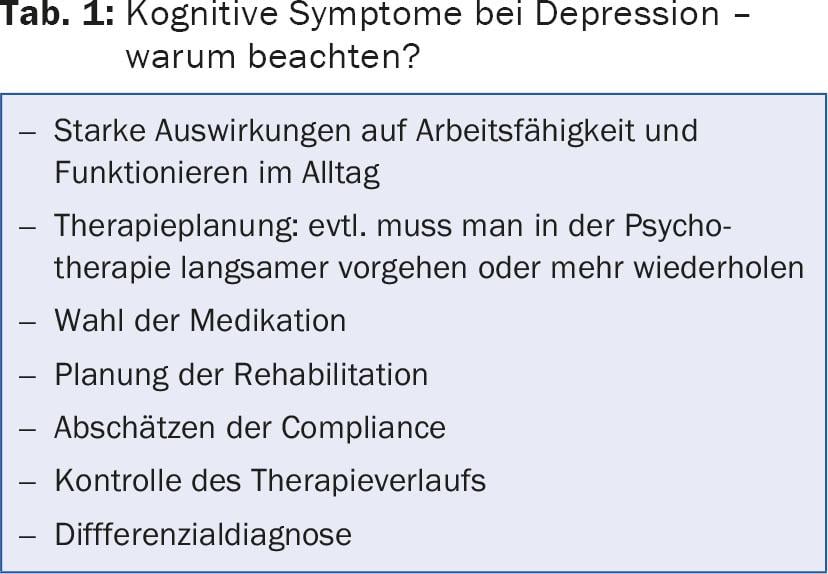

This disregard in diagnosis is inversely proportional to the importance that cognitive dysfunction has on function in everyday life. After the symptom “sad mood”, concentration disorders are the second most important symptom affecting the everyday life of depressed patients. Depressive symptoms also exhibit a high degree of fluctuation – patients report bad days and good days. Cognitive symptoms, on the other hand, are very persistent, hardly fluctuate, and often persist even after the depression has subsided. Prof. Hasler therefore pleaded for more attention to be paid to these symptoms, as they have a strong impact on quality of life and therapy (Tab. 1).

Increased energy expenditure during thinking

A neuropsychological assessment is not always helpful, because it is not the patient’s current cognitive performance that is important, but the change compared to the past. If an academic in a management position suddenly finds himself unable to meet the demands of his job, he may still perform normally on neuropsychological testing. In addition, depressed patients can usually function normally on short tasks, but they have to expend more energy to do so than healthy people, which leads to severe fatigue.

In practice, it may be useful to estimate cognitive function by asking simple questions: Do you have more trouble deciding when shopping? Do you find it harder to concentrate when working? Are you worse at tackling and completing tasks (motivation)?

An important problem is also the emotional rumination resp. Rumination, in which patients repeatedly return to negative, self-centered thoughts. These patients may not have trouble focusing on the negative thoughts, but lack concentration on other cognitive tasks. Furthermore, there is a tendency to reflect past events in a non-specific negative way (“I never loved my husband”, “I was never happy in this job”).

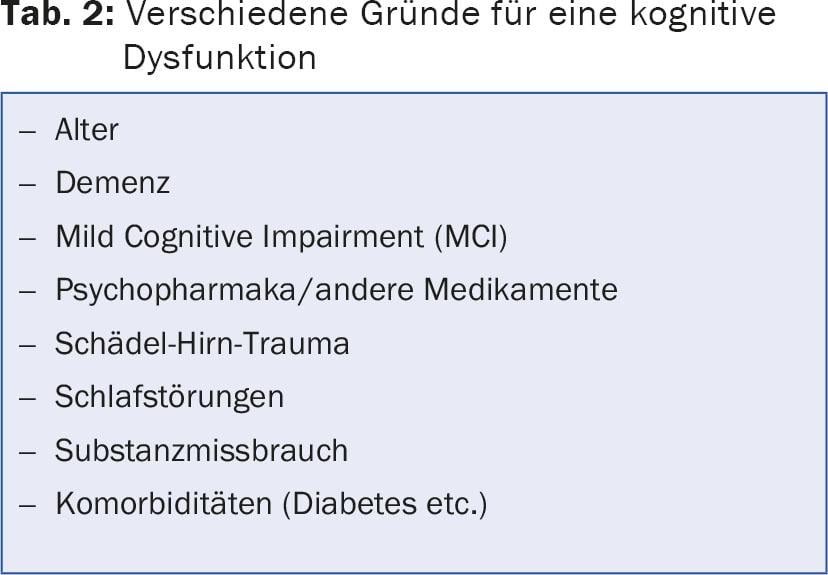

Observe differential diagnoses

During the assessment, it is important to pay attention to the differential diagnoses of cognitive dysfunction (tab. 2). An attempt should be made to assess whether the cognitive complaints subjectively experienced by the patient correspond to the observed deficits. Further, it must be noted whether the deficits are limited or diffuse, subtle or gross. If a side effect or misuse of medication is suspected, the dose should be reduced or, if possible, the medication should be replaced. Diagnostics also include neurological status and basic laboratory (iron status, thyroid parameters, etc.).

Work as a means of rehabilitation

In the past, when dealing with patients who had difficulties in the workplace, the rule was “first train, then place”: first therapy and rehabilitation of the patient, then the search for a new job. This has now been abandoned, as it has become accepted that rehabilitative measures can run parallel to normal work and that work itself can serve as a means of rehabilitation: “First place, then train”. In the USA, such an approach is even required by law. Because the health insurance premiums are paid by the employers, they are more interested in ensuring that the employees do not become ill or that they do not suffer from illness. quickly return to work. In Switzerland, the situation is different, and since companies have little interest in sick employees returning to work as soon as possible, the principle of “first place, then train” has not yet caught on.

One option for vocational rehabilitation of depressed patients is functional re-mediation: the patient practices skills such as communication, planning, control of attention, and problem solving in various modules that are completed in parallel with vocational work. This is a good way to improve learning ability, for example, but slowing down is not. Cognitive training can be dangerous for depressives because if the patient fails the tasks, he or she feels like a failure. More useful are exercise therapies as well as the use of psychotropic drugs, which also improve cognitive abilities. Donepezil and cholinesterase inhibitors, which show some effect in dementia, unfortunately do not work in depressed patients.

Source: KHM Congress, 25-26 June 2015, Lucerne

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2015; 10(9): 43-44