Viral infections of the skin organ often show a pathognomic clinic as well as a characteristic course. This usually allows a rapid diagnostic classification and an immediate start of therapy. This review is limited to macroscopically detectable disease patterns of the integument caused by herpes simplex virus, molluscum contagiosum virus, and varicella zoster virus.

The rapid recognition of a virus-related infection of the skin organ helps to relieve the patient of his suffering or to minimize the symptoms by means of an adequate treatment started immediately, to avoid complications due to a delayed or insufficient therapy and to counteract a passing on of the pathogen. Clinically manifest lesions and/or positive evidence of pathogens should always prompt a search for co-infections with other pathogens. It makes sense to search for the origin of the infection as part of an environmental examination, as well as to identify persons who may already be infected by the patient and – if the findings are appropriate – to provide them with suitable treatment.

Herpes simplex virus: clinical manifestation [1,2,4,6,7,9,11,12]

The herpes simplex virus (HSV), a double-stranded DNA virus, is capable of infecting skin and mucous membranes. Subsequently, the virus may remain in sensory ganglia to form clinical lesions again upon reactivation. Situations that may induce reactivation include. a.o. Conditions involving immunosuppression, UV light exposure, changes in serum sex hormone concentrations (e.g., premenstrual), emotionally stressful moments (“stress”), and neurosurgical procedures on ganglia. Genital lesions due to HSV may be due to type 1 and, more commonly, type 2. Extragenital infections of the skin, on the other hand, are v.a. conditioned by type 1.

Initial contact with HSV predominantly leads to subclinical infection. The manifest primary infection predominantly affects the oral or genital mucosa. Endogenous (e.g. immune status) and exogenous (e.g. UV light exposure) factors determine whether an asymptomatic virus carrier remains or whether clinically palpable lesions become manifest once or repeatedly. Primary infection with HSV has an incubation period of 3-7 days. This is followed by the formation of erythema, in which grouped, itchy-burning, painful vesicles with water-clear contents appear (Fig. 1) . The contents of the vesicles quickly become cloudy, dry off and crust over. Concomitant lymphadenitis, fever, headache, and general ill feeling may occur.

Primary HSV infection is followed by at least one symptomatic relapse in approximately 85% of patients, although the frequency of relapse varies widely. In chronic recurrent HSV infection, prodromal symptoms typically include a feeling of tightness, pulling pain, and/or tickling-itching burning at the site of the lesion. Often, the affected area is smaller and symptoms are milder and less prolonged than in primary HSV infection. The most important complications are HSV encephalitis and eczema herpeticatum (disseminated HSV infection in atopic eczema).

HSV: diagnosis, therapy and prophylaxis

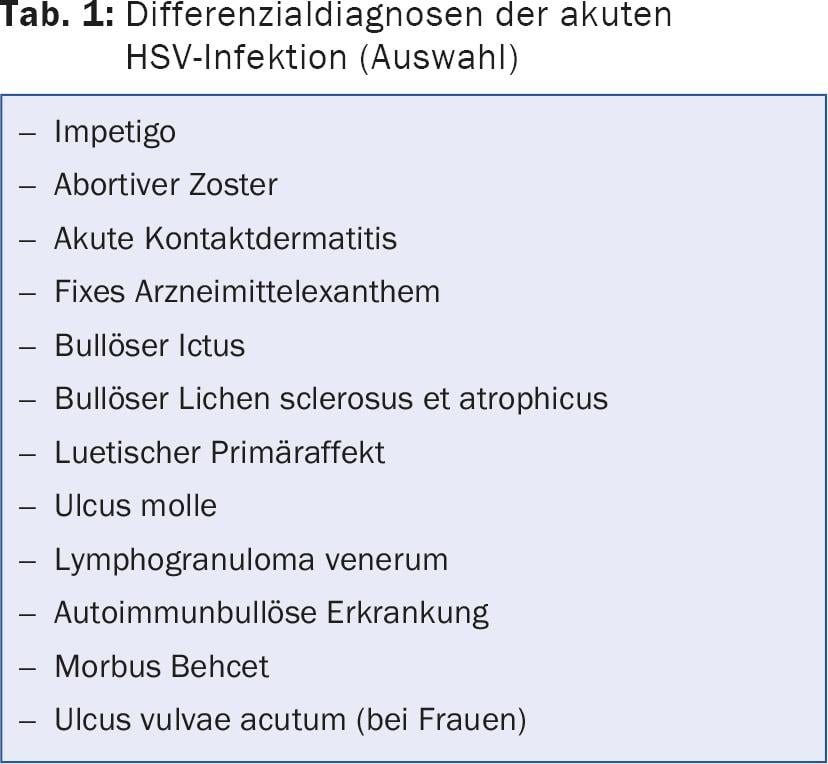

The diagnosis can often already be made clinically. If the picture is unclear, direct pathogen detection can be attempted. Here, the bladder contents collected by smear are subjected to direct antigen detection, e.g., by fluorescently labeled antibodies or polymerase chain reaction. Viral culture is considered the gold standard, but appears too laborious for routine clinical use. Using the Tzanck test, a vesicle base smear can be screened by light microscopy for the presence of ballooned epithelial cells and multinucleated giant cells after Giemsa-Wright staining. A disadvantage is that the sensitivity is low and it is not possible to distinguish between HSV1, HSV2 and VZV. Possible differential diagnoses are listed in Table 1 .

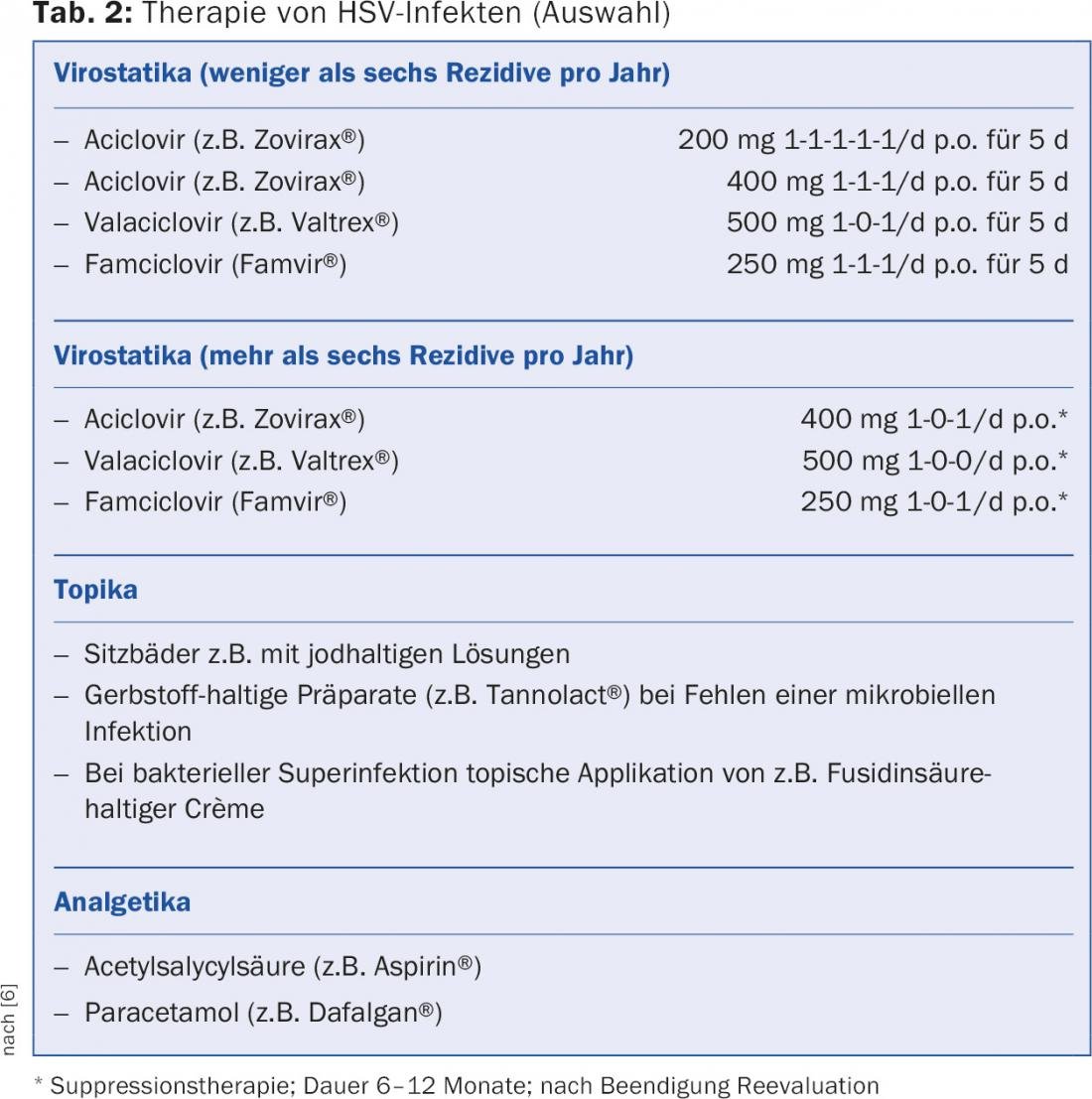

Therapy is multimodal (antiviral and analgesic systemic therapeutics, topical agents) and takes into account the frequency of the lesions that occur. In mild cases, initial infections are primarily treated symptomatically (e.g., mouth rinses, sitz baths, local anesthetics, etc.). Table 2 provides an overview.

Sick persons are generally advised to avoid skin or mucous membrane contact with third parties. Importantly, viral transmission can occur even with macroscopically unremarkable skin and mucosal findings. Proper use of a condom is considered the best way to counteract passing on a genital HSV infection. Studies targeting HSV vaccination are underway [1,2,4,6,7,9,11,12].

Molluscum contagiosum virus [1,2,4,11]

Molluscum contagiosum virus belongs to the group of DNA poxviruses. Transmission occurs via skin-to-skin contact. The virus replicates in the cytoplasm of infected epithelial cells. The incubation period is 14-50 days. After 6-9 months, dell warts induced by the virus may spontaneously regress.

Centrally bifurcated, skin-colored hemispherical papules or nodules 1-10 mm in diameter are characteristic (Fig. 2) . They are often found grouped or loosely disseminated, usually excluding the hairy head and the palmae and plantae. Occasionally, there are complaints of lesional pruritus. Typical complications are scratch excoriations due to itching with scarring healing, impetiginization as well as stigmatization with exclusion (kindergarten, school, etc.).

The clarification can mostly be limited to the macroscopic findings. Histologic confirmation is rarely required in cases of clinical doubt. Differential diagnoses are milia, histiocytomas and pedunculated soft fibromas.

Due to the self-limiting nature of the disease, a wait-and-see approach is occasionally adopted. We favor removal of mollusks as soon as possible to counteract autoinoculation, infection of third parties, social exclusion, and possible complications. Different therapeutic procedures are in use: after topical anesthesia (e.g. EMLA® cream) lesional expression of the highly contagious molluscum via central porus with egg skin forceps, excochleation with the sharp spoon, flat ablation by means of Curette as well as therapy with the pulsed dye or CO2 laser. Other suitable methods include topical application of potassium hydroxide solution (InfectoDell®), application of Immiquimod (Aldara®) or cryotherapy.

Varicella zoster virus (VZV) [1-5, 8-11]

After chickenpox, reactivation of the virus persisting in the glial cells of the dorsal root ganglia may result in a unilateral painful sensation with the appearance of characteristic zoster lesions in the corresponding dermatome (“shingles”). People aged 50 and over, people under immunosuppression, people after previous surgical measures on the spinal ganglia, and local trauma are particularly affected. Initial segmental pain is characteristic. Subsequently, after 3-5 days, grouped, segmentally arranged vesicles appear on a reddened base, which heal crustily (Fig. 3 and 4) . In the acute stage v.a. HSV infection, erysipelas, acute contact dermatitis, impetigo, and bullous ictus should be excluded. Typical complications include ocular involvement (e.g., conjunctivitis, corneal ulcer, iritis with secondary glaucoma), Ramsay-Hunt syndrome (facial nerve palsy, vertigo, hearing loss), postzosteric neuralgia a.o.

The clinical picture often allows a reliable diagnostic classification. If the picture is unclear, direct pathogen detection can be attempted. Here, the bladder contents collected by smear are subjected to direct antigen detection (e.g. fluorescence-labeled antibodies, polymerase chain reaction). Furthermore, there is the possibility of serological verification (VZV-IgM) and other procedures analogous to HSV detection.

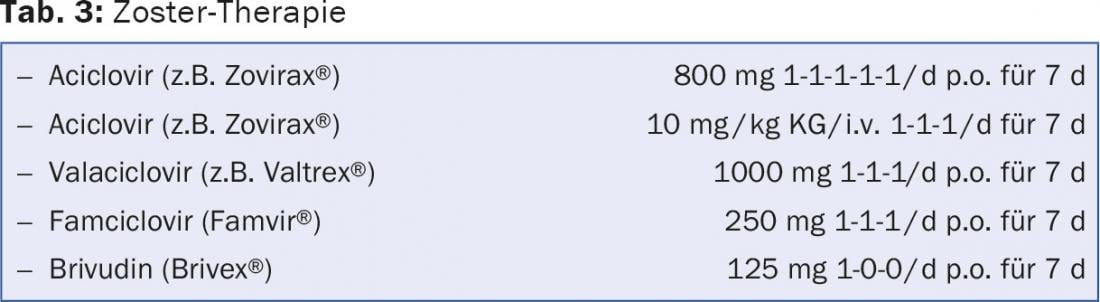

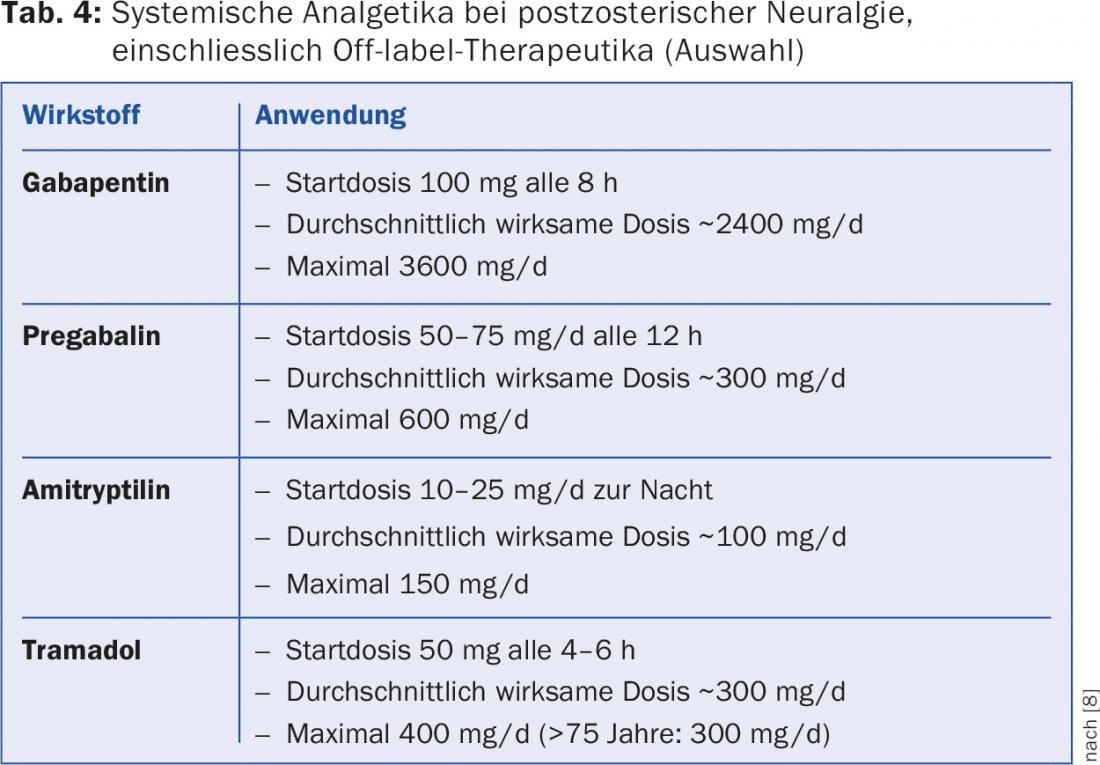

In general, zoster disease requires systemic antiviral therapy – especially in patients over 50 years of age, in lesions on the head and neck, in severe forms on the trunk and/or extremities, in immunodeficient individuals, and in patients with atopic eczema. Therapy should be initiated as early as possible, i.e. if possible within 72 hours after the onset of skin symptoms (Tab.3). Treatment of postzosteric neuralgia includes topical (e.g., preparations containing lidocaine and capsaicin) and systemic therapeutics (e.g., gabapentin, pregabalin, tricyclic antidepressants) (Tab.4). Opioids are used occasionally, but there is uncertainty about the benefit-risk assessment of long-term use. In extreme cases, ganglion blockade may be indicated.

The Federal Office of Public Health recommends protecting everyone from varicella who has not had it in childhood. Vaccination is therefore recommended in Switzerland for all persons aged 11 to 39 years with no previous history of chickenpox. Recent studies in zoster-negative subjects over 50 years of age have demonstrated a reduction in the incidence of zoster as well as zoster neuralgia.

Literature:

- Abeck D, et al: Common skin diseases in childhood. 4th ed., Springer, 2014.

- Bowden FJ, et al: Sexually transmitted infections: new diagnostic approaches and treatments. MJA 2002; 176: 551-557.

- Cunningham AL, et al: Efficacy of the herpes zoster subunit vaccine in adults 70 years of age or older. NEJM 2016; 375: 1019-1032.

- Dayan L, et al: The sexually transmitted infection “check up”. From Fam Phys 2003; 32: 297-304.

- Eckert N, et al: Varicella and herpes zoster. Ther Umsch 2016; 73: 247-252.

- Gross G: Herpes simplex virus infections. Dermatologist 2004; 55: 818-830.

- Hoeller Obrigkeit D, et al: Vaccines against herpes simplex virus infections. Dermatologist 2007; 58: 465-466.

- Johnson RW, et al: Postherpetic neuralgia. NEJM 2014; 371: 1526-1533.

- Orlova Urman C, et al: New viral vaccines for dermatologic disease. JAAD 2008; 58: 361-370.

- Oxman MN, et al: A vaccine to prevent herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia in older adults. NEJM 2005; 352: 2271-2284.

- Petzoldt D, et al: Diagnostics and Therapy of Sexually Transmitted Diseases. Springer, Berlin, 2001.

- Stanberry LR, et al: Glycoprotein D-adjuvant vaccine to prevent genital herpes. NEJM 2002; 347: 1652-1661.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2016; 11(11): 16-21