The feet are the most mechanically stressed parts of the body: By the age of 78, a person has traveled an average of 200,000 km. Foot problems, which are common in athletes, must be distinguished between acute injuries and slowly increasing pain. The more active the athlete, the more generously and quickly the diagnosis should be carried out in order to be able to make a quick surgical indication if necessary. A clear regimen must be developed for treatment that specifies the type and duration of immobilization, stress and activity, extent of analgesia and thromboprophylaxis, and frequency of follow-up visits. At the latest in the case of delayed progression, further imaging diagnostics must be performed.

In our latitudes, the desire for physical activity, especially in leisure time, has increased sharply in recent years. Increased physical activity or sport is nowadays also practiced more and more by older people. The demand for a well-functioning musculoskeletal system, even in old age, is increasing, especially if you feel mentally fit. This creates a discrepancy between the aging musculoskeletal system and the demands placed on its resilience. Nowhere can this be better illustrated than on the foot, because this part of the body, mechanically speaking, is probably subjected to the most stress in the course of life. It is important that each person or patient becomes primarily aware of what the foot does throughout life. A person takes about 10,000 steps per day in transit, which is equivalent to about 7 km. So, at about 78 years of age, a person has traveled a distance of 200,000 km. For very athletic individuals, this number is much higher. This stress on the feet adds up every day, and much like a car tire that is “worn out” after years of wear and tear, the feet will also be “worn out” one day.

Most common acute injuries to the feet

Foot problems that occur during sports are divided into acute injuries and slow-onset injuries or pathologies. In the case of acute injuries, an accident is usually the cause. Here, for example, a distinction is made between anatomical and osseous injuries (usually fracture), osteochondral lesions, and ligamentous or tendinous lesions. Among osseous lesions around the foot, malleolar fracture remains the most common, followed by fractures at the Lisfranc joint line with base fractures at the metatarsal-V or a lesion at the metatarso-phalangeal(MTP) joint. Osteochondral lesions most commonly affect the upper ankle joint (OSJ), and second most commonly the MTP-I joint. The OSG also leads in ligament injuries, followed by capsular ligament injuries at the Lisfranc joint line and around the MTP joints. The Achilles tendon lesion remains the most common tendon lesion on the foot, probably followed by the peroneal tendon injury. The most commonly missed primary injuries are capsular ligament injuries at the Lisfranc joint line and the tibialis anterior lesion, but the tibialis posterior lesion is less common .

In case of clinical suspicion of these lesions, imaging by MRI should be performed as soon as possible and with appropriate presentation to the specialist when the diagnosis is confirmed (Fig. 1) . The symptoms of the more acute injuries are always similar to those of classic inflammation with tumor, dolor, rubor, calor or functio laesa.

Most common causes of slowly increasing pain

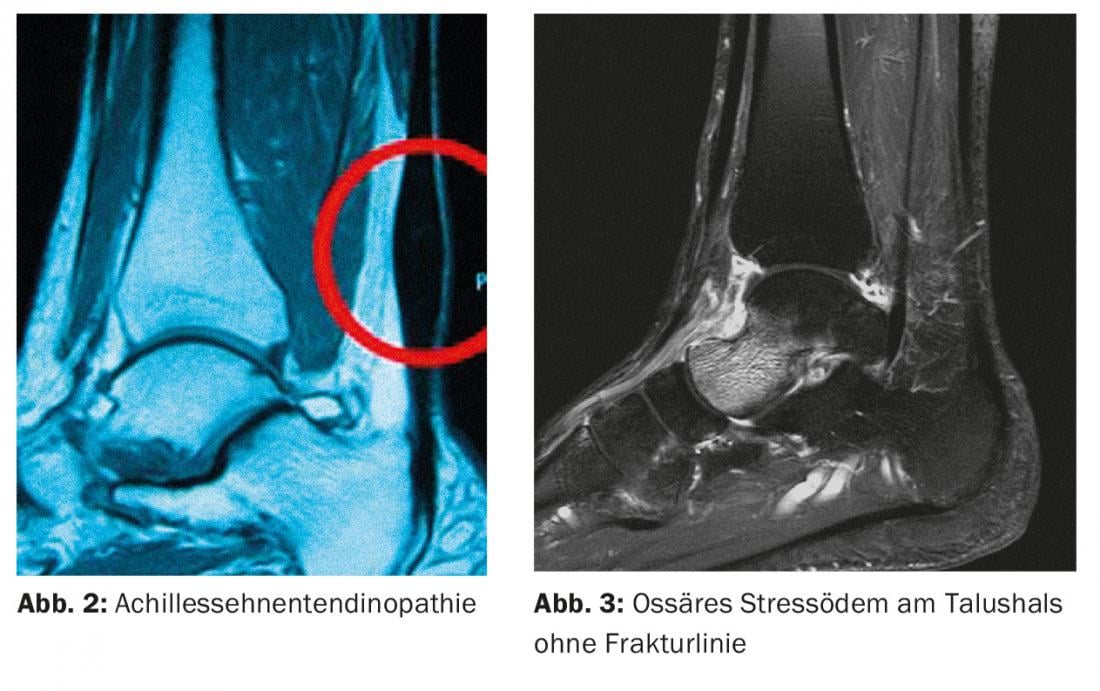

The occurrence of sudden or slowly increasing pain without trauma is more commonly seen in athletes than acute injuries. For these long-standing conditions, the treating physician should be familiar with the most common differential diagnoses. In bone, this is the osseous stress response, often referred to radiologically as a stress fracture. In tendons, this is tendinitis or tendinopathy, which is primarily degenerative and occurs due to microlesions (Fig. 2). Joint pain is most often triggered by joint instability, an osteochondral lesion, or a so-called arthropathy, e.g., a mechanical overload reaction, incipient or activated osteoarthritis, or even the onset or relapse of a rheumatic condition.

Medical history, clinical examination and imaging

The symptoms, clarifications as well as forms of therapy described below apply to acute injuries as well as to other pathologies. The most frequent reason for consultation remains pain, less frequently restricted function or even a deformity with an altered gait pattern. In the case of a nonspecific clinic, it is important anamnestically to elicit the mechanism and force involvement. The patient’s bone quality, age and also previous injuries must be taken into account. This information already gives a clear indication of the structures that may have been violated.

In the clinical examination, one goal is to assign the pain to an anatomical structure. Now a tentative diagnosis can be made. In most cases, however, further diagnostics are necessary in the case of foot injuries or prolonged courses of pain. This can already be performed primarily or, in the case of a non-satisfactory course, secondarily despite having started therapy.

At the ankle joint, at least one x-ray of the OSG ap and lateral is needed, and for midfoot injuries, a conventional x-ray of the foot dp/ oblique/lateral. If this does not confirm the diagnosis, referral to a foot specialist may be appropriate. In most cases, the physician will primarily prescribe an MRI of the hindfoot or forefoot. Additional computed tomography or even spect tomography is only used if there is a clear suspicion of an osseous lesion or joint affliction. Ultrasound-trained examiners can often avoid further evaluation by MRI or CT.

Precisely defined load buildup

When treating the injury, a clear scheme should be worked out if possible. This should answer questions such as type and duration of immobilization, stress and activity, extent of analgesia and thromboprophylaxis, and frequency of follow-up visits. If there is any uncertainty, it may also be worthwhile at this stage to briefly check with a specialist or even refer the patient.

The treatment of active athletes or even professional athletes is basically no different from that of non-athletes. Basically, however:

- The more active the athlete, the more generously and quickly the diagnosis should be carried out in order to be able to make a quick surgical indication if necessary.

- The better the patient’s compliance, the more functional the follow-up treatment should be aimed at.

- The more professionally a sport is practiced, the more often the athlete benefits from accompanying physiotherapy and close-meshed care.

In the case of professional athletes, incapacity for work must also be defined on a regular basis. As athletes progress, they often need more education and a more defined load buildup.

How to proceed in case of delayed progression?

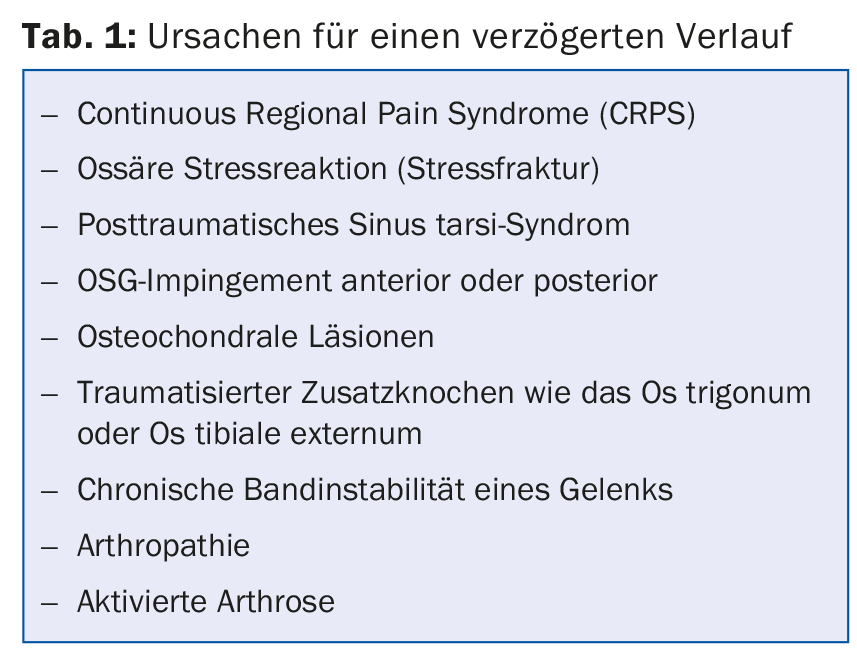

At best, an injury heals after a few weeks. The accompanying physician should be able to recognize the reasons and signs of delayed progression. These can also be described as complications after trauma (Tab. 1) . Further image diagnostics must be performed at the latest in the event of delayed progression. Most of the causative diagnoses can be further treated conservatively on a primary basis. If there is insufficient knowledge of these diagnoses, referral to a specialist is certainly advisable here as well, often simply because the patient is unsettled by the delayed course. This makes it all the more important to monitor the patient closely and to provide advice and support in cases of delayed progression. If the attending physician realizes that the patient is not completely satisfied with the actions and information provided, referral to a specialist is warranted.

Prognoses about the course or the final result are only possible on an individual basis. Bone edema, for example, can last weeks to months. The more acute and vigorous it is seen on imaging, the more likely it is to be symptomatic (Fig. 3) . However, there are more often asymptomatic bone edemas on the foot at physiological loading sites, especially in active athletes. Accordingly, statements about the significance of edema must be cautious.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2016; 11(4): 16-18