Addictive behaviors are more common in patients with bipolar disorder than in the general population. Not only the risk for alcohol and tobacco addiction, but also for behavioral addictions such as gambling addiction, sex addiction, shopping addiction or Internet addiction is significantly increased in this population. To what extent do the comorbid conditions influence each other and how can bipolar patients be helped to get away from addiction? Are different therapeutic measures indicated here than for otherwise “healthy” addicts?

“In the prospective epidemiological Zurich study (1978-2008), we found a cumulative incidence of 34% for severe (major) affective disorder according to DSM IV from 20 to 50 years of age,” said Prof. Jules Angst, MD, Psychiatric University Hospital Zurich. However, bipolar disorders are vastly underestimated by DSM and ICD criteria compared to depressive disorders. “Using DSM IV diagnostics, we identified 32.5% major depressive disorder (MDD), but only 1.2% bipolar I and 2.2% bipolar II disorders. DSM 5 diagnostics also show significant deficiencies in this regard. Modifying the DSM 5 criteria, the ratio comes to about 4:6 (bipolar/unipolar depressive disordered) in those under 50 years of age – this is shown by not yet published data.”

Addictions significantly more common than in the general population

Between the ages of 30 and 40, alcohol abuse was found in a quarter of the bipolar patients (according to DSM IV) in the Zurich study; at the age of 50, the figure even rose to a third. Alcohol abuse is consequently a serious problem in this population with increasing age and is reflected in an approximately eightfold increase in risk compared to the normal population (depressives have an approximately threefold increased risk in this regard). Bipolarity also plays a role in the abuse of cannabis and sedatives. Prevalence rates are higher than for depressed individuals. “Bipolar patients also smoke significantly more frequently than the general population and also than MDD patients. However, in the Zurich study, we were able to observe a significant drop in the one-year prevalences, probably not least due to the public fight against smoking since 1999,” explained Prof. Angst. Between 1999 and 2008, rates decreased from 54% to 26% for bipolar patients, from 40% to 11% for MDD patients, and from 23% to 7% for controls.

Tobacco addiction

Tobias Rüther, M.D., Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Ludwig Maximilian University, Munich, Germany, also confirmed that the risk for tobacco dependence is significantly increased in bipolar patients compared to the general population. According to a meta-analysis of 51 studies from 16 countries, the odds ratio for current smoking is 3.5 (95% CI 3.39-3.54) [1]. Research also shows that nearly one in two cigarettes in the U.S. is smoked by people with a psychiatric disorder. The tobacco industry is aware of this target group and addresses them specifically. “Smoking is the leading preventable cause of death from psychiatric illness. It leads to a loss of 25 years of life in this population (compared to ten years in people without psychiatric comorbidity) and markedly reduces quality of life. It is also a predictor of suicidality, even when controlling for possible confounders,” Dr. Rüther said.

The relationship between tobacco smoking and bipolar disorder is bidirectional and multifactorial. First, underlying vulnerability to affective disorders (including bipolar disorder) may be caused by a permanent change in neurophysiology as a result of tobacco use. On the other hand, in smokers with bipolar disorder:

- an earlier onset of the first depressive or manic episode

- more suicide attempts in the past

- comorbidly frequent anxiety disorders and substance abuse

- a longer duration of illness with more severe symptoms (longer hospitalization).

“In some studies, tobacco smoking also correlates with rapid cycling, more affective episodes, and increased risk for psychotic episodes,” the speaker said. “What you have to remember when dealing with these patients is that the motivation to stop smoking is basically the same in mentally ill patients as it is in mentally healthy patients.”

Where does addiction come from?

The main reason for continuous smoking is nicotine addiction. “Smokers smoke because of nicotine and die from the products of combustion,” Dr. Rüther noted. Nicotine binds to nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the brain. By activating these receptors, it triggers the release of various neurotransmitters, including dopamine, norepinephrine, glutamate, serotonin, GABA, and β-endorphin. These in turn influence perception and behavior. Among other things, they lead to feelings of happiness, satisfaction, alertness, increased cognitive performance, appetite inhibition, and the reduction of anxiety, tension, fear, and pain. Thus, the body is “rewarded” for nicotine use and at the same time “punished” with withdrawal symptoms if the next cigarette does not follow. The “reward” is less pronounced than, for example, with cocaine, heroin or alcohol, but nicotine causes greater difficulties in achieving abstinence compared to the other substances. This is mainly due to the extremely strong psychological dependence. Addiction-associated cues, i.e. key stimuli such as stops, etc., can be found everywhere in everyday life and lead to a veritable “neuronal fireworks display” in the brain of smokers in nicotine withdrawal.

How to fight addiction?

Advice and support from a specialist are therefore mandatory. It is important to specifically address smoking cessation during the consultation. Even minimal medical consultation (“Do you smoke? Have you considered quitting?”) achieves significantly higher abstinence rates than standard consultation. Intensive consultation is even more effective. However, the greatest effect in terms of abstinence is achieved through counseling combined with pharmacotherapy. According to guidelines, all physicians should recommend that their smoking patients quit tobacco use (level of evidence A).

Drug therapy options include bupropion (Zyban®, contraindicated for patients with bipolar disorder), varenicline (Champix®), and therapeutic nicotine (long-acting such as 16- or 24-hour patches or short-acting such as gum, lozenges, microtabs, and inhalers). A combination of the active ingredients is possible. “With varenicline, we achieve abstinence rates of about 33%. Patches in the dosage of 25 mg bring rates of 27% and combinations of 37%. Bupropion, which is not approved for bipolar disorder, is in the same range, with abstinence rates of 24%,” the expert explained. The effects of smoking cessation on mental health are at least as good, and in some cases better, than those of antidepressants [2]. A randomized controlled trial by Evins et al. [3] showed that maintenance therapy with varenicline and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) can achieve continuous tobacco abstinence in patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder (the difference from placebo plus CBT remained significant until the end of follow-up at week 76).

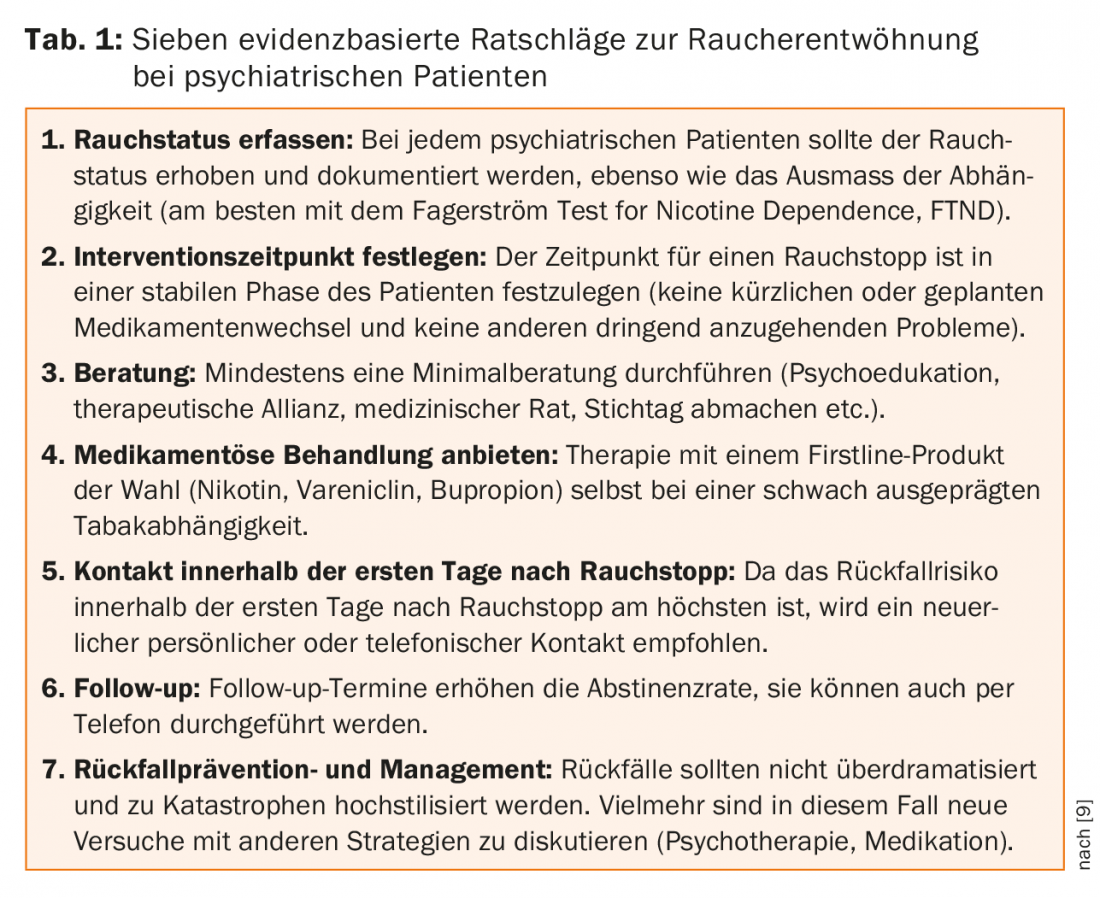

The above points can be summarized in seven pieces of evidence-based advice (Table 1).

Bipolar disorder and behavioral addictions

Whether “behavioral addictions” such as gambling addiction, Internet addiction, shopping addiction, or sex addiction can really be considered addictive disorders, and what relevance the “addictive” component has compared to the compulsive and impulsive components, has been the subject of repeated controversy in the past, which is reflected in the currently differing classifications of such disorders. In principle, in the case of non-substance-related addictions, it can be assumed that the psychotropic effect is produced by the body’s own biochemical changes (and not by externally supplied substances). These processes are triggered by a specific excessive rewarding behavior. According to Prof. Dr. med. Michael Rufer, Clinic for Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, University Hospital Zurich, behavioral addiction can often be interpreted as a kind of “self-medication”. It can be a coping attempt for guilt and stressful life experiences, or a distraction from stress and anxiety for lack of tolerance for negative affect, used to compensate for feelings of inferiority, or to regulate negative emotions such as depression or boredom.

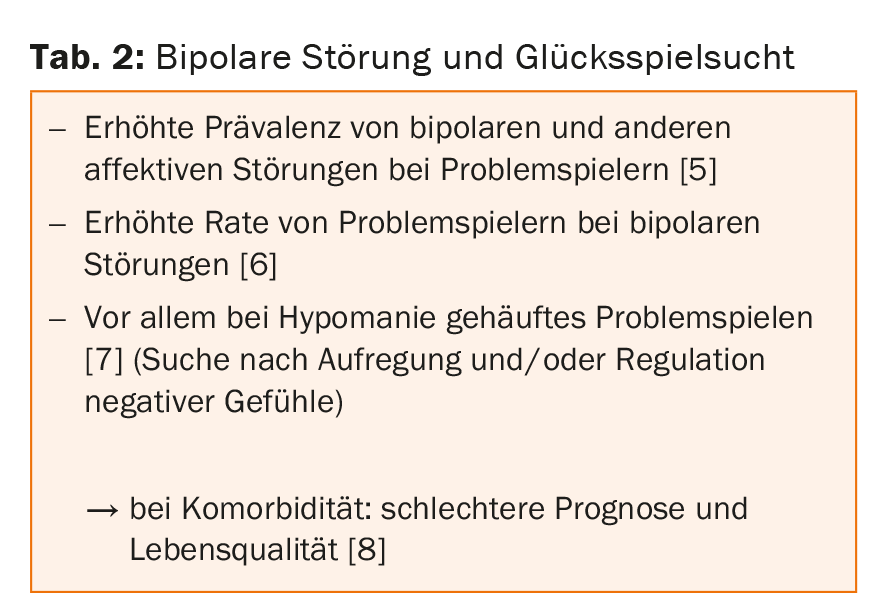

The overlap between bipolar disorder and behavioral addictions is large. This is illustrated by the example of “gambling disorder” ( tab. 2). According to the DSM 5 criteria, one component of the definition of this addiction is: “Gambling cannot be better explained by a manic episode.

In the case of excessive gambling during a manic episode, the diagnosis of “gambling disorder” is only made if the gambling cannot be explained by the manic episode, i.e., if it also occurs outside of manic episodes.

And vice versa: the behavior of a person with a “gambling disorder” may resemble a manic episode, with such features no longer observable once the gambling phase is over.

Since behavioral addictions are often comorbid to bipolar disorder on the one hand, but on the other hand may only be an expression of an underlying bipolar disorder, diagnostic screening is recommended [4].

Cognitive behavioral therapy is gold standard

With behavioral addictions, it is important to target motivation to change in the patient. A personal explanatory model (e.g., an individualized assessment of the excessive behavior as an attempt to cope with other problems) as well as a concrete naming of the symptomatology can help here. But be careful: Talking about “addiction” does not always have to be motivating, but can just as well serve the patient as a reason to remain passive (“I am at the mercy of my addiction”). The environment should be included if possible. Depending on the nature of the excessive behavior, abstinence may not be the goal of therapy.

Evidence level Ia has multimodal cognitive behavioral therapy, which can be more symptom- or cause-oriented. The presence of comorbid bipolar disorder does not argue against targeted therapy for behavioral addiction (given stability of bipolar disorder and consideration of possible functional correlates). Serotonin reuptake inhibitors, opiate receptor antagonists, and mood stabilizers (especially in comorbid bipolar disorder) are recommended with level Ib evidence.

Source: 11th Annual Interdisciplinary Meeting of the Swiss Society for Bipolar Disorders, October 24, 2015, Zurich.

Literature:

- Jackson JG, et al: A combined analysis of worldwide studies demonstrates an association between bipolar disorder and tobacco smoking behaviors in adults. Bipolar Disord 2015 Aug 4. [Epub ahead of print].

- Taylor G, et al: Change in mental health after smoking cessation: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2014 Feb 13; 348: g1151.

- Evins AE, et al: Maintenance treatment with varenicline for smoking cessation in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2014 Jan 8; 311(2): 145-154.

- Wölfling K, et al: Bipolar spectrum disorders in a clinical sample of patients with Internet addiction: hidden comorbidity or differential diagnosis? J Behav Addict 2015 Jun; 4(2): 101-105.

- Petry NM, Stinson FS, Grant BF: Comorbidity of DSM-IV pathological gambling and other psychiatric disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry 2005 May; 66(5): 564-574.

- McIntyre RS, et al: Problem gambling in bipolar disorder: results from the Canadian Community Health Survey. J Affect Disord 2007 Sep; 102(1-3): 27-34.

- Jones L, et al: Gambling problems in bipolar disorder in the UK: prevalence and distribution. Br J Psychiatry 2015 Oct; 207(4): 328-333.

- Kennedy SH, et al: Frequency and correlates of gambling problems in outpatients with major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder. Can J Psychiatry 2010 Sep; 55(9): 568-576.

- Rüther T, et al; European Psychiatric Association: EPA guidance on tobacco dependence and strategies for smoking cessation in people with mental illness. Eur Psychiatry 2014 Feb; 29(2): 65-82.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2016; 14(1): 42-44.