About two-thirds of all patients with epilepsies can become seizure-free without intolerable side effects with appropriate and regularly taken antiepileptic pharmacotherapy. Regular medication adherence is most likely to be achieved with the patient as an autonomous acting partner in the doctor-patient relationship in terms of the concepts of adherence and concordance. Repeated routine as well as postictal determinations of serum concentrations of antiepileptic drugs and their appropriate interpretation can support the detection of adherence deficiencies and the optimization of intake practices.

The epilepsies are a group of very numerous and very different chronic brain diseases that have in common the occurrence of unprovoked epileptic seizures.

In most cases, therapy is exclusively symptomatic, i.e., it does not affect the epileptogenic brain pathology itself, but aims at suppressing the symptom “epileptic seizure”.

With antiepileptic pharmacotherapy, approximately two-thirds of all affected individuals can become seizure-free without intolerable side effects [1]. From the patient’s perspective, this means taking one or more medications regularly every day for many years, often for life. Missing a dose even once can lead to the occurrence of a seizure with all the medical and social consequences (injuries, loss of fitness to drive, inability to work). Thus, the success of epilepsy therapy, as well as that of the treatment of other chronic diseases, depends on adherence to therapy as a result of cooperation between patient and physician, which was formerly described by the term compliance, and later and most recently by the terms adherence and concordance.

In the following, the definitions of the three terms will be explained first, and then the term adherence will be used in particular. Hereafter, the importance and causes of poor adherence in the treatment of epilepsy will be discussed. Detection of poor adherence is often not straightforward in practice; in addition to careful and cautious history taking, determinations of serum antiepileptic drug concentrations may play a role, and their use will be explained. Ways are then shown for practice to achieve stable adherence and thus freedom from seizures as a prerequisite for the maximum possible social participation of an affected person.

Since the adherence of an individual patient therefore also has a social dimension (especially in the assessment of fitness to drive or the ability to work and reintegrate), its assessment has a role to play in the socio-medical assessment/appraisal of epilepsy patients, which will be discussed in conclusion.

Definitions

Compliance is the extent to which a patient follows the physician’s instructions. In relation to a prescribed regular intake of medication, compliance thus means the frequency with which a prescribed medication is taken. This makes it a measurable variable, e.g. in the form of a percentage value, which can be used in studies.

The newer term adherence now takes more account of the patient’s perspective in that participation in therapy is based on a conscious decision by the patient. In other words, it is about the extent to which the patient consciously consents to a proposed therapy and then carries it out. The patient is therefore no longer seen merely as an executor of medical prescriptions, but as a person who decides independently about his or her therapy. For this to be possible, however, the patient must be informed in detail by the physician about the advantages, disadvantages and alternatives of a particular proposed treatment. This aspect is now taken into account with the term concordance . This indicates the extent to which a treatment regimen is adhered to through open doctor-patient communication involving the patient’s ideas in the decision-making process. Thus, concordance implies the whole process between physician and patient, which aims at convincing the patient of a proposed treatment in order to reliably carry it out [2].

The three concepts explained thus reflect an evolution in the understanding of the doctor-patient relationship in the implementation of long-term therapies, which must also find its reflection in the medical care of epilepsy patients, as will be shown below.

Epidemiology, significance and causes of poor adherence.

Up to 50% of all patients with chronic diseases who require drug therapy do not take it according to the doctor’s prescription, usually taking less than the prescribed amount. This not only has adverse effects on individual patients, but also unfavorable economic effects on the entire health care system. According to a Swedish study examining the economic relevance of poor adherence, this leads to unnecessary additional expenditure of 40-50% of total expenditure on medicines, depending on the model used. This does not take into account the costs incurred as a result of medical interventions (such as emergency hospitalization) that became necessary as a result of poor adherence [3].

Unfortunately, there are no epidemiological studies that have systematically investigated the frequency and relevance of adherence deficiencies in epilepsy. Only small-scale studies suggest the considerable extent of this phenomenon and its importance in patients who do not become seizure-free despite adequately prescribed medication. In one study, for example, 20 epilepsy patients were given a box of tablets fitted with an electronic device that registered each opening. In this context, opening in accordance with the prescription was shown to be 88% immediately before and 86% immediately after a consultation, and only 67% one month later [4].

That adherence deficiencies are likely to be frequently responsible for the occurrence of seizures is supported by a study in which postictal serum concentrations were compared with the mean of two routinely determined values in 52 patients with 61 seizures. In 44.3% of seizures, postictal serum concentrations were more than 50% lower than the mean of routinely obtained values, which was considered to be a consequence of inadequate medication [5]. Adherence deficiencies are also likely to play a role in triggering status epileptici or sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP) [6,7].

No systematic studies exist to assess the causes of poor adherence. In the above-mentioned publications, various factors are discussed that promote the occurrence of poor adherence and that can often occur in combination in a patient. These are side effects, cognitive dysfunction, psychiatric comorbidities (e.g., adjustment disorders, depression, psychosis, personality disorders), a non-somatic disease concept, primary, secondary, and tertiary disease gain.

Detection of poor adherence

Again, there are no studies evaluating or even comparing the different detection methods. Based on the author’s many years of experience, the most important tool in identifying an adherence problem is a careful and cautious medical history. It is not enough to ask (casually) if the medication is taken regularly. Rather, the intake practice must be inquired about in detail. If no intake aids are used, it must be clarified how a possible medication gap could be noticed. The indication that regular medication intake without aids such as weekly dosettes or electronic alarms could be difficult to achieve even for a physician, if he is a patient himself, also gives the patient room for critical reflection on his intake practice.

Of course, side effects must also be specifically asked about, in addition to which the above-mentioned factors and comorbidities and, above all, the social situation must be kept in mind.

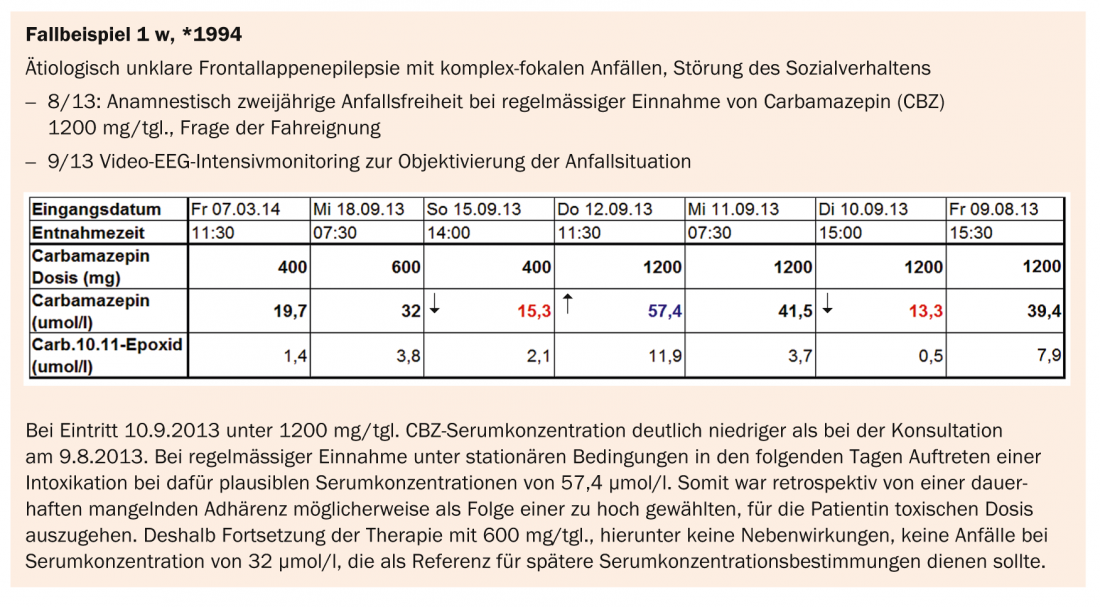

Furthermore, the above-mentioned comparison of postictal serum concentrations with routinely obtained values plays a major role in the author’s daily paxis. A single value, if it is not below the detection limit and significant resorption problems are excluded, usually does not allow a reliable statement on adherence. However, under a constant dose, serum concentrations of a drug should not vary too much with repeated measurements (see case study 1).

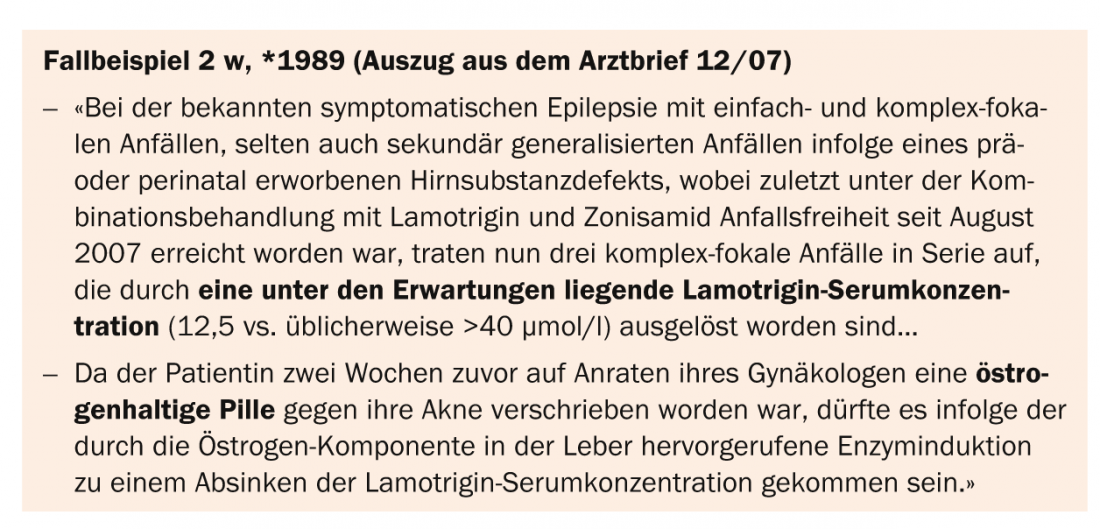

However, stronger fluctuations are not always due to adherence deficiencies, but can also be caused by interactions with changing concomitant medications (see case study 2). Thus, for the assessment of adherence, it is usually not relevant whether a serum concentration determined at a certain point in time is within the so-called reference range of a laboratory or not [8].

The electronic tablet containers mentioned in the above-mentioned studies or even the comparison of prescribed and purchased medication cannot, of course, be applied in daily practice.

Measures to improve adherence – concordance

In the absence of relevant studies, only general indications can be given here, but they can all be derived from the above-mentioned concepts behind the terms adherence and concordance [9]. At the beginning of a successful drug treatment of epilepsy, there is the well-informed patient, who is convinced of the benefit of the intended treatment and consciously agrees to it. The dosing regimen should be as simple as possible, taking into account the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the selected medication (for most antiepileptic drugs, distribution over two single doses is quite sufficient).

The use of aids such as weekly dosettes (with removable day sliders) and/or electronic alarm clocks should be encouraged.

The patient should handle all management of obtaining and taking medications themselves, unless there are cognitive limitations that do not allow this. Already at the beginning of the treatment it should be pointed out that intake irregularities may occur and that these can and must be discussed openly again and again both on the part of the physician and the patient, otherwise there is a risk that the patient will take more medication with the risk of more side effects than is actually necessary.

Once an ingestion error leads to a seizure or the results of serum concentration determinations suggest adherence deficiencies, this should not be discussed with the patient in an atmosphere in which he or she feels like a convicted offender. Rather, after careful analysis of the intake practice, it must then be a matter of jointly seeking solutions to improve adherence. After a seizure triggered by an ingestion error, expansion of the medication is usually prohibited. In cases where psychiatric comorbidity affects adherence, it should be addressed with appropriate therapy, if necessary.

Socio-medical evaluation of poor adherence.

In the socio-medical evaluation/assessment of a patient with active epilepsy affecting the ability to work and reintegrate, it must be assumed that antiepileptic pharmacotherapy is a reasonable treatment that the patient must adequately perform within the scope of his duty to cooperate and mitigate damages [10]. At first glance, this view may seem to run counter to the atmosphere of goodwill and mutual trust called for above in order to achieve concordance, taking into account the patient’s views in the doctor-patient relationship and reducing the patient to the executor of medical orders, but ultimately it appeals to the social responsibility of the responsible patient in our very efficient solidarity-based insurance system. Therefore, in terms of the concept of adherence, it may well be communicated at the beginning of antiepileptic treatment and thus become the basis of a patient’s consent to antiepileptic pharmacotherapy.

Conclusions

Regular medication is an important prerequisite for freedom from seizures. As with other chronic diseases, it cannot be assumed to be always present. Comprehensive information about the advantages and disadvantages as well as alternatives of a proposed pharmacotherapy and a reproach-free discussion about possible adherence deficiencies are of central importance. Antiepileptic pharmacotherapy is a reasonable treatment in the sense of the obligation to cooperate and mitigate damages in social insurance or pension insurance.

Thomas Dorn, MD

Literature:

- Brodie MJ, Kwan P: Staged approach to epilepsy management. Neurology 2002; 58(8 Suppl 5): 2-8.

- De las Cuevas C: Towards a clarification of terminology in medicine taking behavior: compliance, adherence and concordance are related although different terms with different uses. Curr Clin Pharmacol 2011; 6: 74-77.

- Hovstadius B, Petersson G: Non-adherence to drug therapy and drug acquisition costs in a national population – a patient-based register study. BMC Health Serv Res 2011; 28: 326.

- Cramer JA, Scheyer RD, Mattson RH: Compliance declines between clinic visits. Arch Intern Med 1990; 150: 1509-1510.

- Specht U, et al: Postictal serum levels of antiepileptic drugs for detection of noncompliance. Epilepsy Behav 2003; 4: 487-495.

- DeLorenzo RJ, et al: A prospective, population-based epidemiologic study of status epilepticus in Richmond, Virginia. Neurology 1996; 46: 1029-1035.

- Lathers CM, et al: Forensic antiepileptic drug levels in autopsy cases of epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 2011; 22: 778-785.

- Patsalos PN, et al: Antiepileptic drugs–best practice guidelines for therapeutic drug monitoring: a position paper by the subcommission on therapeutic drug monitoring, ILAE Commission on Therapeutic Strategies. Epilepsia 2008; 49: 1239-1276.

- Faught E: Adherence to antiepilepsy drug therapy. Epilepsy Behav 2012; 25: 297-302.

- Dorn T: The assessment of work and rehabilitation capacity in epilepsy. Epileptology 2008; 25: 174-181.

InFo Neurology & Psychiatry 2014; 12(4): 10-14.