Congenital syndromes may show ocular involvement. These include Down syndrome, Marfan syndrome, myotonic dystrophies, metabolic diseases with lysosomal storage disorders, and neurofibromatosis. The ophthalmological examination is of great relevance, on the one hand to confirm the diagnosis, on the other hand to control or correct pathologies of the eye.

Congenital syndromes may show ocular involvement. These include Down syndrome, Marfan syndrome, myotonic dystrophies, metabolic diseases with lysosomal storage disorders, and neurofibromatosis. In this context, the ophthalmolo-gical examination is of great relevance, on the one hand to confirm the diagnosis, and on the other hand to control or correct pathologies of the eye.

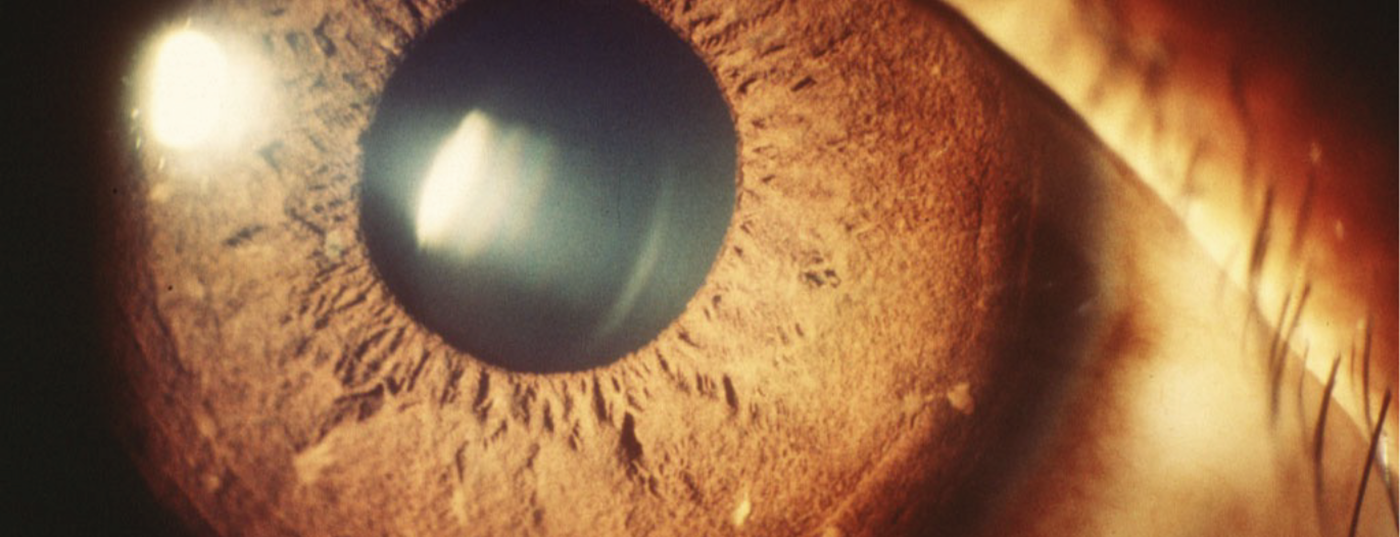

Neurofibromatosis is one of the common hereditary diseases with an incidence of 3:10,000. Ocular manifestations in neurofibromatosis may involve the eyelids, iris, orbit, and optic nerve. The so-called Lisch nodules are considered the main diagnostic criterion in screening for neurofibromatosis, as they are present in more than 95% of patients over 6 years of age and the test for this is non-invasive. These are small, roundish, sharply circumscribed hamartomas of the iris that can be detected by examination with a slit lamp (Fig. 1).

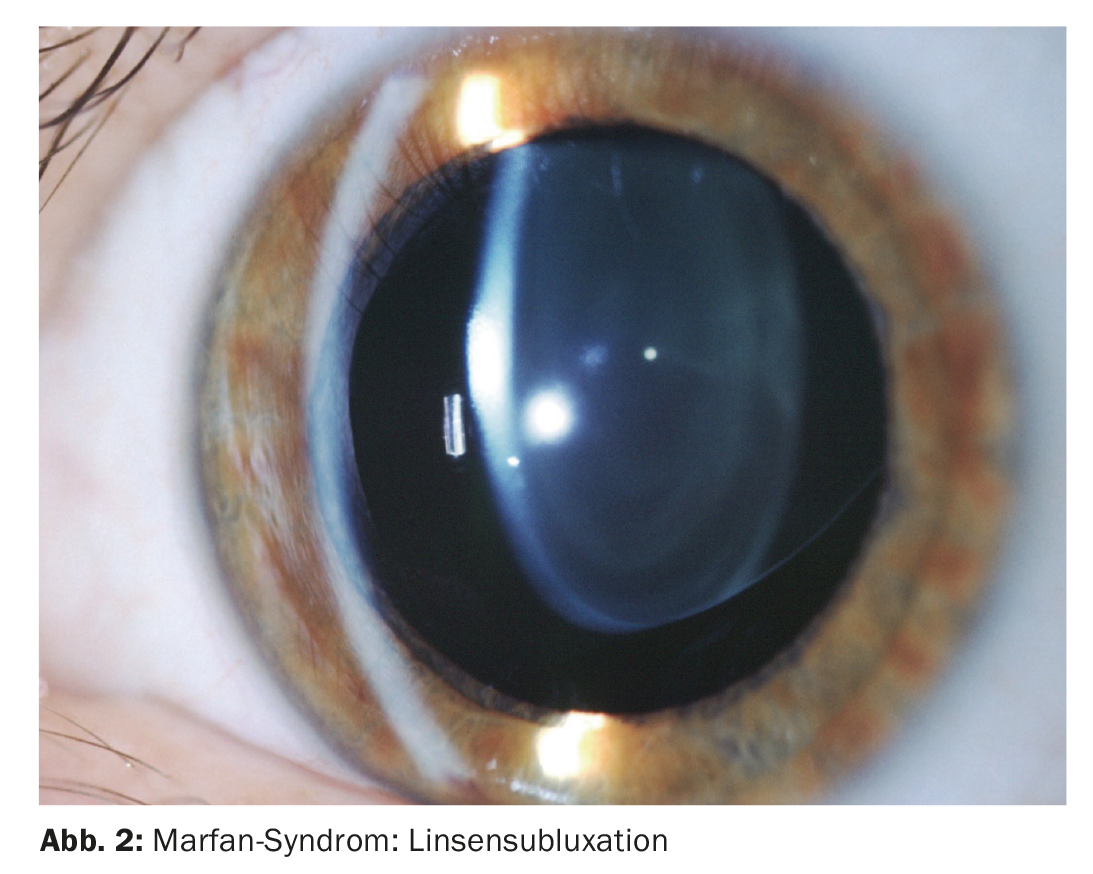

In Marfan syndrome, lens dislocation occurs bilaterally and symmetrically. Because the zonular fibers are often intact, accommodation is maintained in these patients. Other ocular involvement in Marfan syndrome includes chamber angle abnormalities with consecutive glaucoma, retinal detachment due to retinal weak spots, cornea plana, and strabismus (Fig. 2) .

Vascular diseases

Basically, a distinction is made between arteriitic and non-arteriitic occlusions. In non-arteritic retinal artery occlusion , the cause is usually due to an embolus, which may lead to a perfusion defect in the ophthalmic artery, central retinal artery, or in a branch of the central artery. The perfusion disturbance with consecutive visual loss may be transient or permanent. In the elderly, the most common sources of emboli are fibrin and cholesterol from ulcerated plaques in the wall of the carotid artery. Other causes of retinal vascular occlusion include vascular constriction, aneurysm dissecans, reduced perfusion in circulatory failure, and vasculitis. Cardiac causes are more common in younger patients (<45 years).

Unfortunately, the treatment of arterial occlusion is not satisfactory. In clinical practice, treatment measures such as acute lowering of intraocular pressure and bulbar massage are recommended to improve retinal perfusion. Few patients show improvement in visual acuity in the spontaneous course.

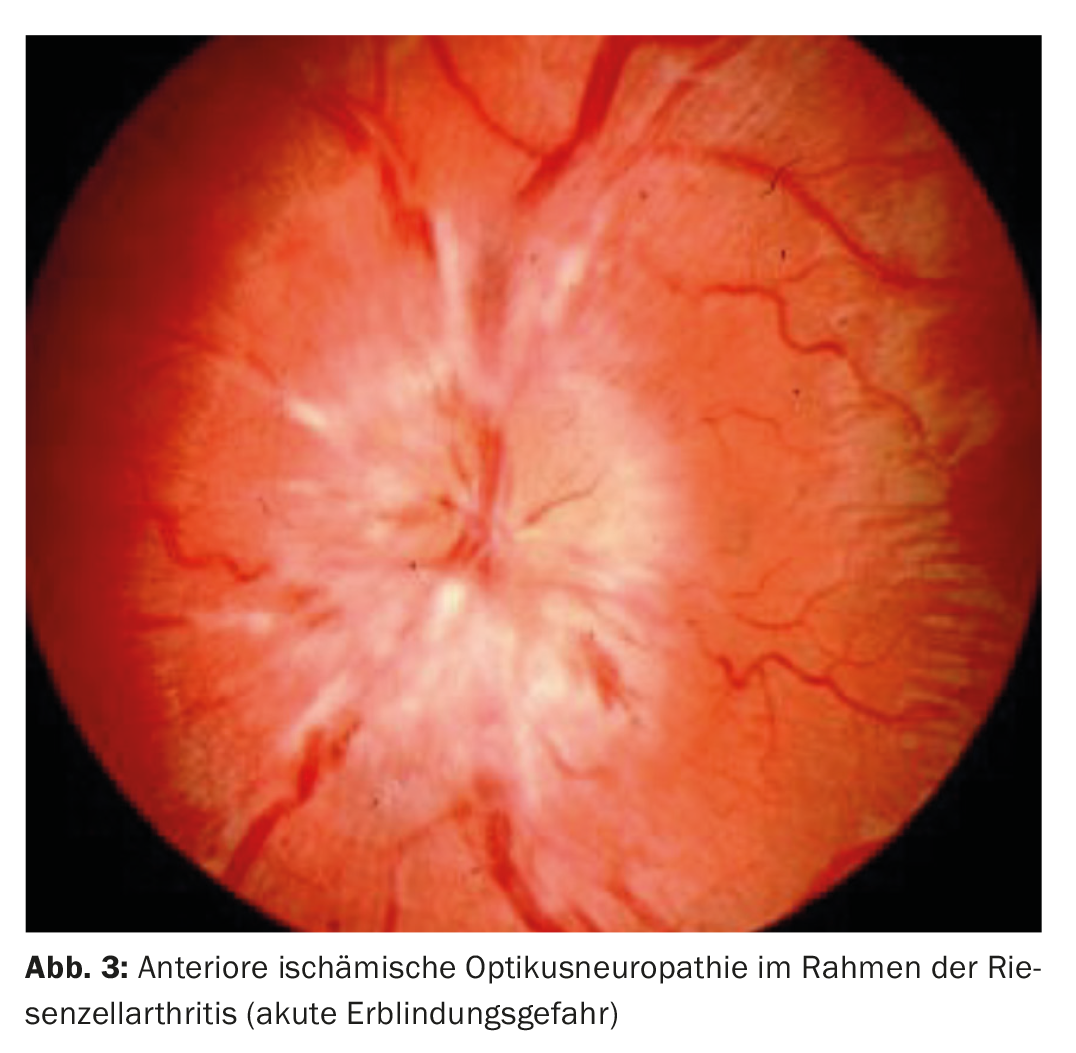

The arteriitic cause is Horton’s arteritis temporalis, also known as giant cell arteritis. Although it underlies central retinal artery occlusion as a cause in only 1 to 4%, it is the most common systemic vasculitis in those over 50 years of age. The ocular manifestation is expressed as granulomatous inflammation of the arterial wall of the ophthalmic or retinal artery. Giant cell arteritis may more commonly lead to anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (Fig. 3).

In temporal arteritis, typical clinical symptoms include headache, chewing pain, neck pain, paresthesias at the temple, fever, and weight loss. Acute phase reaction testing with erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, and platelets are diagnostic. A biopsy of the temporal artery is diagnostic, but unfortunately a negative result of the biopsy does not exclude temporal arteritis with certainty, so that in some cases immunosuppressive therapy must still be given to prevent further occlusions, especially in the fellow eye. Arteritis temporalis is an emergency, as there is a risk that the partner eye may also be affected without prompt therapy.

Amaurosis fugax is a special situation. This results in a sudden, severe, painless and temporary loss of vision. Amaurosis fugax is a transient ischemia of the retina (arteria centralis retinae) or the optic nerve head (Aa. ciliares posterior), which then causes a temporary visual deterioration. These attacks usually last for about 2-3 minutes. Subsequently, visual acuity returns to normal. A transition to manifest arterial occlusion is possible. Both in complete retinal artery occlusion and in amaurosis fugax, an internal or neurological evaluation is mandatory.

Ophthalmologic controls after arterial occlusion are necessary to detect and treat secondary diseases like retinal neovascularization as well as neovascular secondary glaucoma in time.

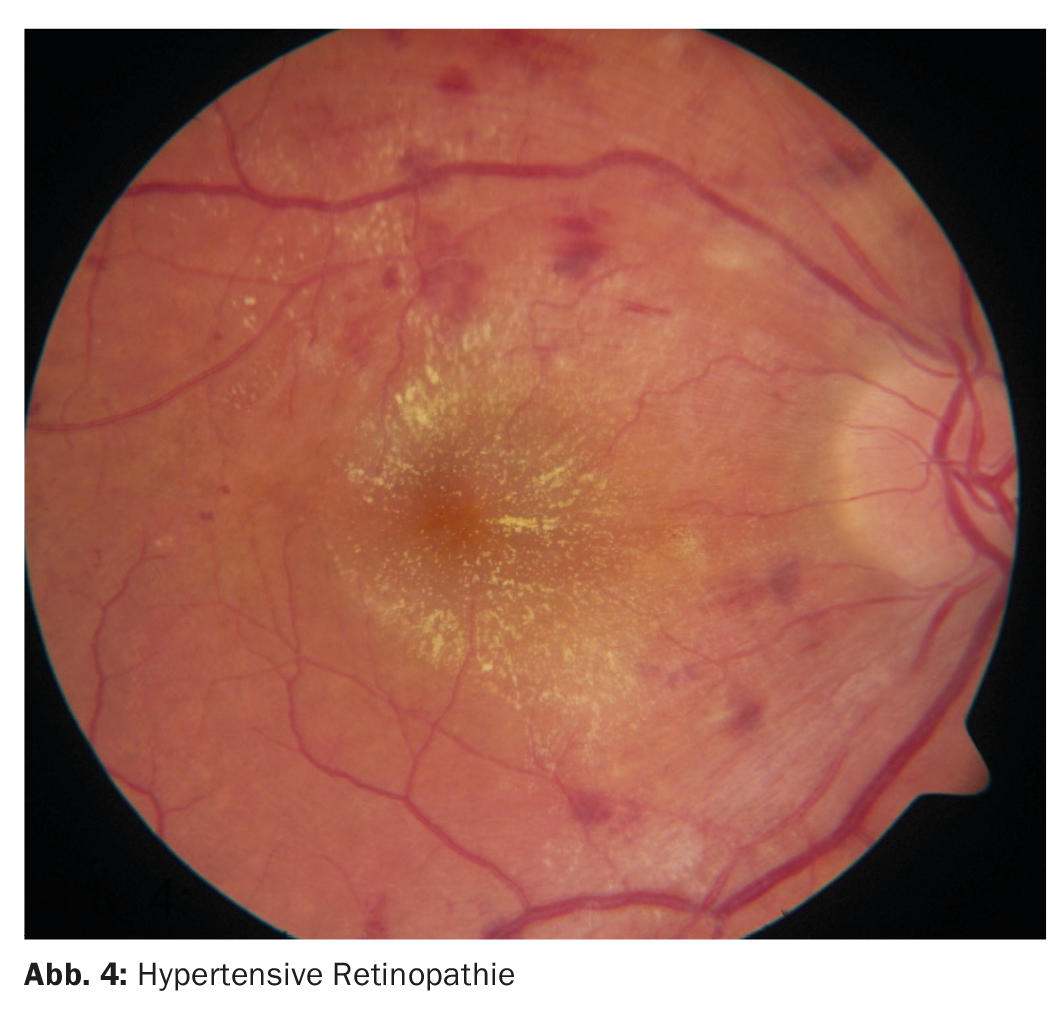

Hypertensive retinopathy

Arterial hypertension can affect the perfusion at the retina, choroid as well as at the optic nerve and thus lead to pathological changes. The extent depends on the severity and duration of hypertension.

Hypertensive changes in the retina are manifested by flame-like hemorrhages in the superficial layers of the retina and Cotton-Wool spots as signs of occlusion of the capillary arterioles and ischemic infarction of the inner retinal layers. Longstanding hypertension is made visible by sclerotically altered vessels called copper and silver wire arteries. Another sign of chronic hypertension is lipid exudates, which occur due to vascular permeability disturbance of the vessels (Fig. 4) .

Ocular ischemia syndrome is a rare condition involving chronic hypoperfusion of the eye. This occurs as a result of marked stenosis of the internal carotid artery. Patients with ocular ischemia syndrome may also have a history of amaurosis fugax secondary to retinal emboli. Most often, patients complain of slow visual loss that persists for weeks or even months.

Both the anterior and posterior segments of the eye are affected. Fundus examination reveals narrowing of the arterioles, dilatation of the veins, hemorrhage especially in the periphery, and cotton wool foci. In advanced stages, retinal neovascularization and neovascularization of the iris and the chamber angle may occur, resulting in vitreous hemorrhage as well as secondary glaucoma.

Diabetes mellitus can cause visus-threatening changes in the eye. Diabetic retinopathy is the most common cause of reduced visual acuity in working-age individuals. There are two stages of the disease: At the beginning it is called non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy. This can progress after years into proliferative diabetic retinopathy, which without adequate treatment can lead to blindness (Fig. 5) .

Ophthalmological check-ups and treatment depend on the stage of the disease. In the presence of macular edema, a drug called a vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) inhibitor is injected into the vitreous cavity. Advanced diabetic retinopathy with retinal neovascularization is treated by panretinal laser photocoagulation. Already ischemic areas of the retina are treated and “switched off” with the treatment. By eliminating the diseased tissue, their need for oxygen is reduced, and thus, on the one hand, the healthy retinal areas can be better supplied with oxygen, and on the other hand, less VEGF is then produced, thus preventing the formation of new vessels.

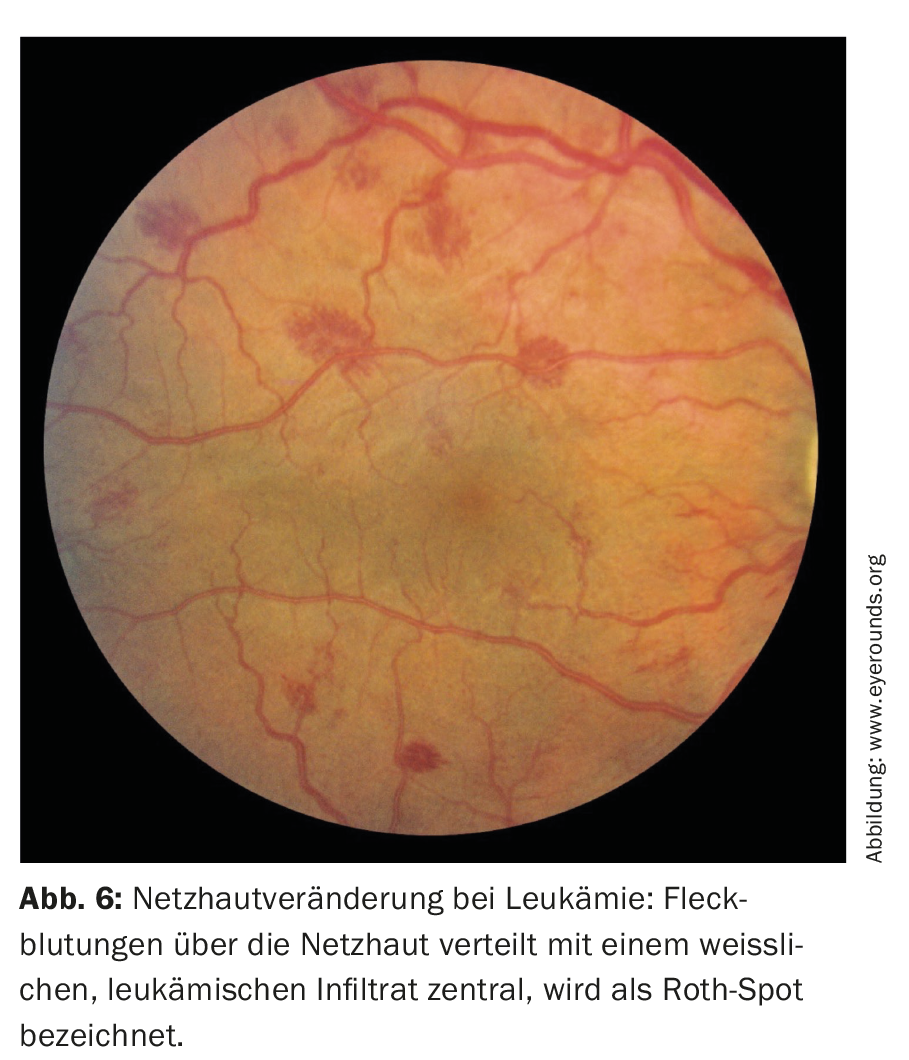

Blood diseases

Various blood disorders, which is also known as blood dyscrasias, can result in varying degrees of eye involvement. These include hyperviscosity, thrombocytopenia, all forms of anemia including sickle cell anemia, and leukemia.

In anemia, retinal hemorrhage may occur with low hemoglobin or thrombocytopenia. Symptoms in the form of visual loss or spot perception depend on both the location and severity of the hemorrhage.

Sickle cell retinopathy is most common in the HbSc form of the disease, but it can also occur in the HbSS form. This leads to occlusion of the retinal vessels, especially in the periphery of the retina. Due to the resulting ischemia of the retinal periphery, retinal neovascularization may occur.

Patients with Sichercell anemia should remain under regular ophthalmologic control, since due to the peripheral findings, patients remain asymptomatic for a long time. If left untreated, this can lead to further complications such as hemorrhage into the vitreous cavity or tractional retinal detachment resulting in blindness. Once retinal neovascularizations form, laser treatment of the ischemic areas of the retina is necessary to induce regression of these and avoid further complications.

Patients with hyperviscosity syndromes such as polycythemia, multiple myeloma, dysproteinemia, and leukemia may experience fundus changes such as venous dilatation, retinal hemorrhage, and optic disc swelling due to direct infiltration of the optic nerve. Patients with leukemia show additional leukemic infiltrates called Roth spots (Fig. 6).

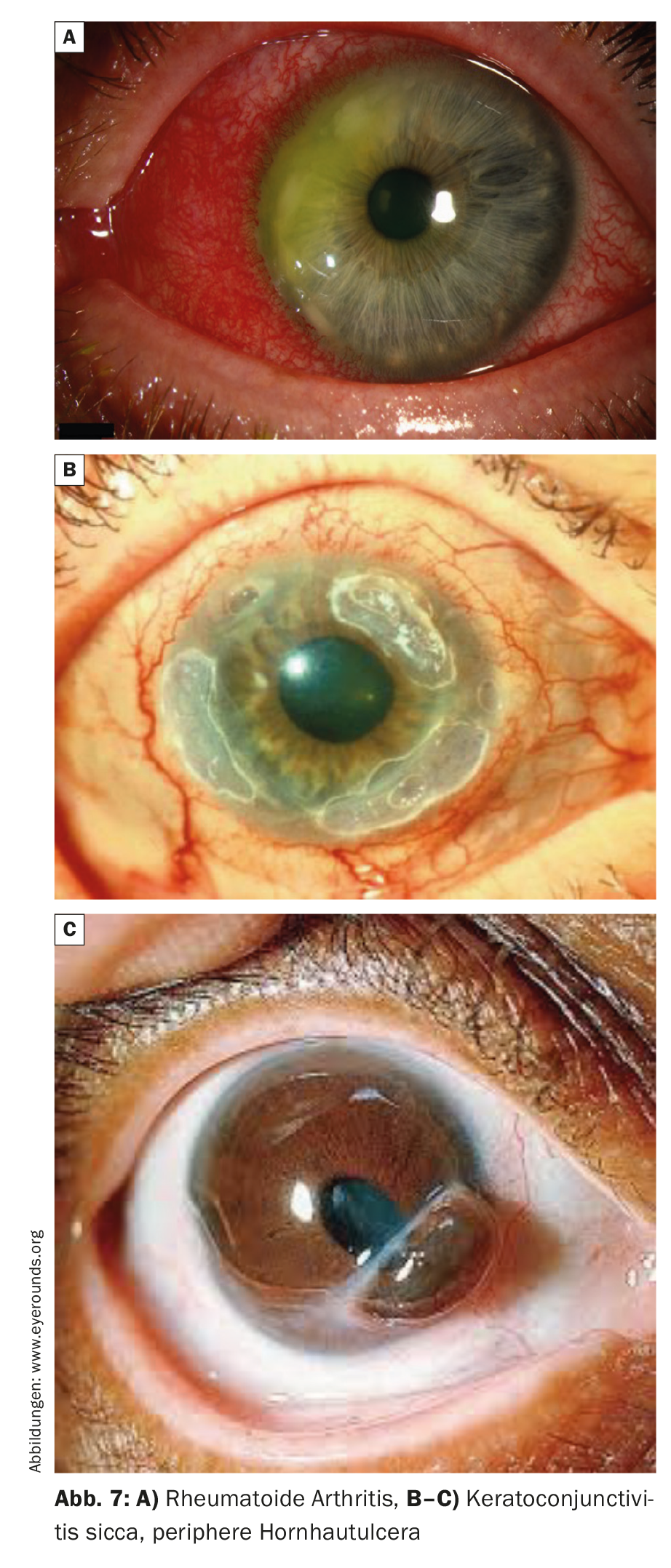

Autoimmune diseases

Spondyloarthropathies: Up to 25% of patients with spondyloarthropathies develop intraocular inflammation affecting the anterior segment of the eye, termed anterior uveitis. Patients usually complain of photophobia, redness, and decreased vision. In this case, evaluation by an ophthalmologist should be urgent, as treatment with topical steroids and dilating agents of the pupil is necessary to prevent long-term damage. Topical steroid therapy should also be monitored by an ophthalmologist, as it may be associated with side effects such as cataract formation and increased intraocular pressure.

Rheumatoid arthritis: Ocular manifestation of rheumatoid arthritis is most commonly observed in patients with more active and severe forms of the disease and in patients with extra-articular involvement. Apart from dry eyes, which is a common manifestation in various rheumatoid diseases, other ocular pathologies can be observed. Common inflammatory manifestations include episcleritis, scleritis, peripheral corneal ulcers, and uveitis (Fig. 7).

Episcleritis is inflammation of the superficial tissue overlying the sclera. Patients usually complain of mild to moderate pain. Morphologically, there is localized or diffuse redness of the eye.

Scleritis can sometimes appear clinically similar to episcleritis. However, severe, deep pain is a distinguishing feature of scleritis. In the pronounced case, scleromalacia perforans may occur, where melting of the sclera to blubus perforation may occur.

Peripheral corneal ulceration is another manifestation of rheumatoid arthritis that leads to ocular perforation. Patients with rheumatoid arthritis who have peripheral corneal ulceration or scleritis are at increased risk for developing potentially fatal systemic vasculitis. Primary care physicians should monitor patients with active rheumatoid arthritis for symptoms and signs of episcleritis, scleritis, corneal ulceration. Patients presenting with these ocular conditions should be referred for ophthalmologic care.

Systemic lupus erythematosus: Patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) have ocular manifestations similar to those seen in rheumatoid arthritis. These include dry eye, scleritis, and peripheral corneal ulceration. Nevertheless, patients with systemic lupus erythematosus may have more severe manifestations such as retinal vasculitis. Lupus vasculitis may also affect the optic nerve and lead to ischemic optic neuropathy. Evidence of retinal vasculitis may precede the diagnosis of SLE in some cases.

Ocular side effects of systemic drugs

Some medications can cause side effects to the eye if used chronically. These should be detected in time, as most can lead to irreversible changes. The pathologies may manifest in different localizations of the eye:

Cornea: Cornea verticillata (vortex keratopathy) is characterized by a whorl-like corneal epithelial deposition. This change usually does not cause visual deterioration, even if the deposits are located in the area of the visual axis. However, some patients perceive halos around lights. Medications that cause cornea verticillata include amiodarone and antimalarials such as chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine .

Lens: Lens opacification may be caused by cataractogenic drugs. These include primarily steroids, both in local and systemic application. Chlopromazine causes dose-dependent opacification of the lens capsule. Allopurinol also causes dose-dependent lens opacification.

Retina: Antimalarials, chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine, can cause retinopathy, especially at the macula, in rare cases. Both the daily dosage and the total duration of ingestion play a role. Since the drug is often used in chronic diseases (such as rheumatoid diseases) and the toxicity to the retina is irreversible, regular screening is recommended.

Tamoxifen can cause ocular complications in the form of crystalline deposits in the inner retinal layers. In the later course, atrophic changes may occur, which may be accompanied by limitation of central visual acuity.

Optic nerve: Ethambutol may cause optic neuritis, color vision disturbance, and visual field defects as ocular side effects. Toxicity is dose and therapy duration dependent.

Amiodarone may also cause optic neuropathy due to demyelination. Initially, there is bilateral optic disc swelling, which persists for a prolonged period of time even after discontinuation of the drug and may lead to atrophy of the nerve fiber and, accordingly, may be associated with a temporary or permanent visual field defect.

Take-Home Messages

- Systemic diseases can lead to eye involvement. Ophthalmological examinations are relevant in the case, firstly to confirm the main diagnosis, and secondly to control or remedy the eye condition by early detection.

- Vascular diseases of the eye can have different causes. Inflammatory genesis is an ophthalmic emergency. The primary goal here is to avoid blindness from the partner eye.

- Autoimmune diseases can also affect the eye. Pathologies usually manifest as intraocular inflammation (uveitis), scleritis, corneal ulcer, or even vascular pathologies (vasculitis or occlusions).

Literature:

- Scheie HG, et al: Ocular manifestations of systemic diseases 1971; 17 (2): 1-51.

- Cho H: Ocular Manifestations of Systemic Diseases: The Eyes are the Windows of the Body. Hanyang Med Rev 2016.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2021; 16(9): 10-14