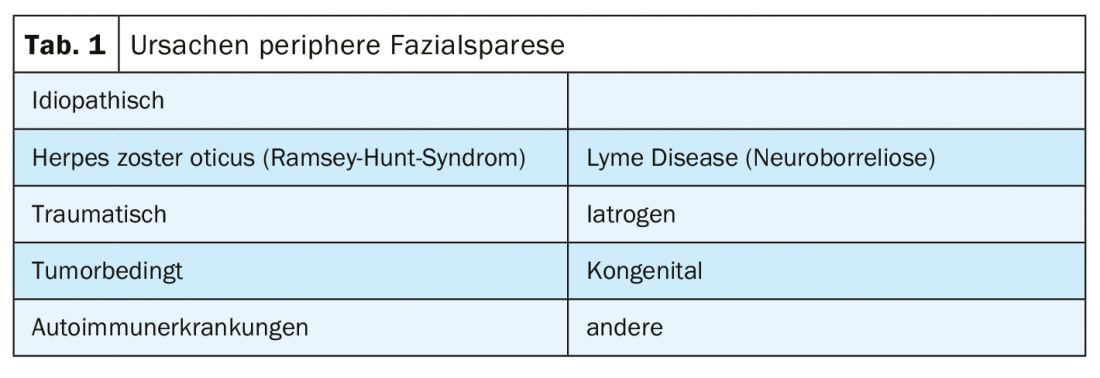

Peripheral facial nerve palsy is the most common isolated cranial nerve palsy and can have a variety of causes. The idiopathic form represents the largest group of facial paresis, accounting for over 70%. Some researchers suspect a connection with an infection caused by herpes simplex viruses.

In peripheral paresis, absent or weakened facial expressions of the entire face are noticeable, whereas in central paresis, the mobility of the forehead and eye closure are preserved. The typically drooping corner of the mouth and incomplete eyelid closure with positive bark phenomenon are symptoms of failure of the motor portions of the facial nerve. Acute peripheral facial nerve palsy is often accompanied by other symptoms. These occur due to damage to the sensory, gustatory and secretory fibers of the seventh cranial nerve: Patients experience reduced salivary secretion (submandibular and sublingual glandula), loss of taste (anterior two-thirds of the tongue), failure of the stapedius reflex and consequent hyperacusis, and reduction of lacrimal secretion from the affected half of the face, depending on the level of nerve damage.

Although in 70-85% of cases acute Bell’s palsy recovers completely, pareses of other causes often recover incompletely or develop noticeable or even painful symptoms of defect healing [1]. In both the acute and chronic phases, paresis leads to functional limitations in speech (dysarthria), eating (remnants in the cheek pouches), drinking (anterior drooling), vision (failure to clean the ocular surface), or expressing emotions (facial expressions). Patients suffer from a significantly reduced quality of life and the risk for the occurrence of mental disorders such as depression is significantly increased in individuals with peripheral facial nerve palsy, especially in female patients, compared to healthy subjects [2].

In the early phase of facial nerve paresis, depending on the cause of the paralysis and the severity of the nerve damage (neuropraxia, axonotmesis or neurotmesis), it can be estimated whether and when a complete recovery can be expected or whether a chronic paresis with defect healing will develop. For patients who cannot be guaranteed a full recovery, both expert interviews and studies indicate that waiting or practicing with nonspecific templates are contraindicated. If the patient practices smiling or whistling in front of the mirror independently and without instruction during the paralytic phase, asymmetry of the facial features may develop due to hyperactivity of the healthy half of the face even with a good prognosis. In patients with an unfavorable prognosis, early and undifferentiated motor training increases the expression of chronic paresis and secondary sequelae (e.g., synkinesias).

Regardless of the prognosis, practical counseling of patients in the acute phase regarding eye protection and assistance for everyday life is essential. Eye protection in cases of limited eyelid closure is a key treatment focus and is also strongly recommended in the guidelines [3]. Patients experience practical tips on dry eye care, proper application of the watch glass dressing, or cleaning residuals in the drooping lower eyelid as helpful as advice on chewing without biting the cheek or drinking without drooling. In the early stages, many patients are unsure of what behaviors are beneficial to their recovery or what they should avoid. Detailed answers to questions about staying in the sun, wind, dust, showering, or whether chewing gum is favorable or unfavorable usually do not find a place in the consultation with the family doctor or in the emergency room. This is where a consultation with a therapist can fill a gap.

As soon as the first micromovements become visible, patients with an unfavorable prognosis should be guided to perform targeted movements while maintaining symmetry. That therapeutic treatment can achieve positive effects is demonstrated by various studies such as the reviews by Pereira et al. [4] or Cardoso et al. [5] according to. Conservative facial rehabilitation is provided by speech therapists, physical therapists, or occupational therapists with appropriate additional training. Successful rehabilitation aims at regaining all facial movements and achieving symmetrical facial features. At the same time, it acts preventively against the development of secondary damage or reduces it in order to achieve the greatest possible patient satisfaction and quality of life. Mime therapy according to Beurskens [6] or neuromuscular training according to Diels [7] are among the possible treatment approaches. While biofeedback with mirrors or surface EMG have beneficial effects, electrical muscle stimulation should only be used with completely denervated muscles. Used nonspecifically, electrostimulation can exacerbate secondary damage in the chronic phase.

Successful therapy concepts that have been studied for their effectiveness include the following building blocks:

- Consultation and education

- Neuromuscular training adapted to the degree of regeneration of the nerve

- Massage and self-massage, possibly lymphatic drainage

- Relaxation techniques

- individual home training program

From the acute phase onwards, work can be done on facial symmetry and, by targeting isolated muscle movements or coordination exercises, mobility can be promoted and the development of synkinesias can be prevented as best as possible. In the chronic phase, symptoms of defect healing such as synkinesias, contractures, autoparalysis, or painful spasms can be relieved by central learning.

Medical education teaches the classification of peripheral facial nerve palsy into six degrees of severity according to the House Brackmann Score developed in 1985. From a therapeutic point of view, grading systems that are as easy and time-saving to use as House Brackmann scoring, but additionally evaluate the different facial regions individually, take static and dynamic assessments into account, and include secondary consequences such as synkinesias or contractures, are preferable [8]. The Sunnybrook Facial Grading System [9], developed in Canada, fulfills all of the above criteria, while providing good inter- and intrastriate reliability, and maps changes during therapy or through surgical correction. A differentiated assessment of severity can provide an initial assessment in the early phase of whether and how intensively the affected person will need support in their recovery process and can document the healing process by a score of 0 – 100 (a score of 100 corresponds to normal facial function).

|

Take-Home Messages for the Practitioner

|

Following the WHO directive to define health not as the absence of disease but as a state of physical, mental and social well-being, questionnaires are used to assess quality of life in many disease conditions. For facial paralysis, this can be done using the Facial Disability Index and the Facial Clinimetric Evaluation (FaCE) questionnaire in a German version by Volk et al. [10] be used to record subjective sensitivities and assessments. The two questionnaires can be used to document the course of therapy and to clarify the need for therapy.

During the initial contact with a trained therapist, after a careful examination, a decision can be made together with the patient whether counseling is sufficient or whether therapy on a low-threshold or intensive scale is necessary. Although early intervention is recommended by many experts, improvement can be achieved with conservative therapy even in the chronic stage.

Literature:

- Thielker J, et al: Surgery for lesions of the facial nerve. Laryngorhinootology, 2018. 97(6): 419-434.

- Huang B, et al: Psychological factors are closely associated with the Bell’s palsy: a case-control study. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technolog Med Sci, 2012. 32(2): 272-279.

- Baugh, R.F., et al: Clinical practice guideline: Bell’s palsy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 2013. 149(3 Suppl): S1-27.

- Pereira LM, et al: Facial exercise therapy for facial palsy: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical rehabilitation, 2011. 25(7): 649-658.

- Cardoso JR, et al: Effects of exercises on Bell’s palsy: systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Otol Neurotol, 2008. 29(4): 557-560.

- Beurskens CH, Heymans PG: Mime therapy improves facial symmetry in people with long-term facial nerve paresis: a randomised controlled trial. Aust J Physiother, 2006. 52(3): 177-183.

- Diels HJ: Facial paralysis: is there a role for a therapist? Facial Plast Surg, 2000. 16(4): 361-364.

- Fattah, A.Y., et al: Facial nerve grading instruments: systematic review of the literature and suggestion for uniformity. Plastic and reconstructive surgery, 2015. 135(2): 569-579.

- Neumann T, et al: Validation of a German version of the Sunnybrook Facial Grading System. Laryngo- rhino- otology, 2017. 96(3): 168-174.

- Volk GF, et al: Facial Disability Index and Facial Clinimetric Evaluation Scale: validation of the German versions. Laryngo- rhino- otology, 2015. 94(3): 163-168.

FAMILY PRACTICE 2019; 14(9): 38-39