Antibiotics are a very important pillar of modern medicine for the purpose of prophylaxis and control of bacterial infections. But used too often or over too long a period of time, the emergence and spread of resistant pathogens is favored. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), antibiotic resistance is one of the greatest threats to health today. What are the implications of this in clinical practice?

There has been an increase in infections with antibiotic-resistant bacteria worldwide. The excessive use of antibiotics creates selection pressure: bacterial strains that have resistance to the antibiotic can continue to multiply and spread. Infections caused by extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing enterobacteria, carbapenem-resistant enterobacteria, and vancomycin-resistant enterococci are increasingly difficult to treat [1]. In the clinical context, this means that the effectiveness of existing therapies is decreasing and, as a consequence, morbidity and mortality are increasing. To address the problem of antibiotic resistance, various national initiatives have been launched, including the Swiss Center for Antibiotic Resistance (ANRESIS), which continuously monitors the domestic resistance situation [2]. The most important data are published monthly in the Bulletin of the Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH). While resistance in Gram-negative bacteria such as Escherichia coli (E. coli) is increasing sharply in Switzerland, infections with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) have decreased [3]. This is primarily due to a reduction in hospital-acquired MRSA infections, with advances in infection prevention, including improved hygiene measures, to thank for this [4,5]. “The situation with regard to MRSA has improved greatly,” explains Prof. Philip Tarr, MD, Co-Chief Physician and Head of Infectious Diseases and Hospital Hygiene at the Baselland Cantonal Hospital, Bruderholz [6].

Targeted and criteria-driven use of antibiotics

The main reasons for antibiotic resistance are an increase in antibiotic consumption in animal fattening and excessive antibiotic use in human medicine. The more antibiotics are prescribed, the more resistance develops. In human medicine, about 75% of all antibiotics are prescribed in primary care practices, according to Prof. Tarr [6]. Up to 50% of these are not indicated, or an antibiotic with too broad an effect is prescribed, or the duration of treatment is too long [6,7]. Between 2000 and 2015, global antibiotic consumption increased by 65% [8]. In the UK, one in five antibiotics is prescribed unnecessarily; in the USA, the figure is as high as one in three [7]. Targeted use of antibiotics is an important approach to reducing antibiotic resistance and is advocated by current guidelines from various professional societies. In addition to the guidelines for the treatment of infectious diseases of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID), the Swiss Society of Infectious Diseases (SSI) has published recommendations adapted to specific circumstances in Switzerland [9,10].

Short duration of antibiotic treatment and avoidance of quinolones.

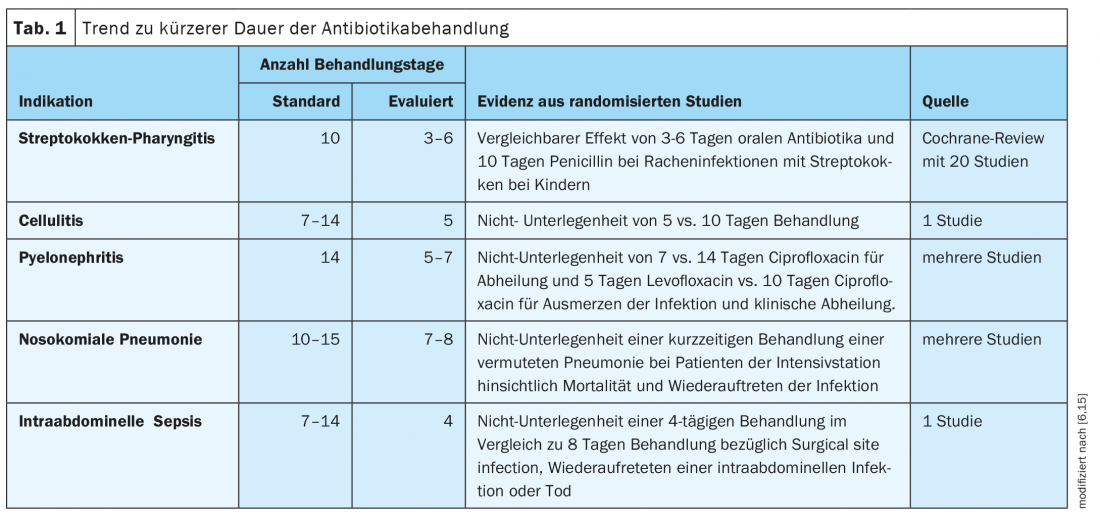

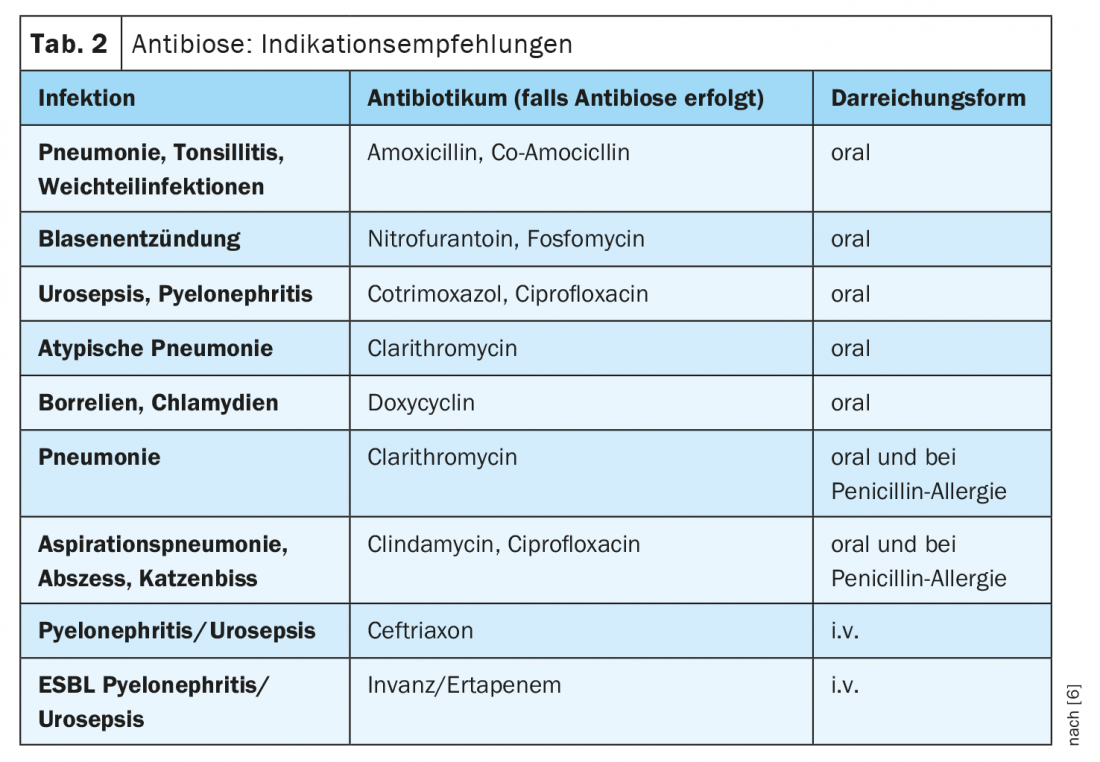

The longer the period of antibiotic treatment, the more selection pressure is generated in the direction of resistance development. Therefore, the motto is to rather give antibiotics short and hard, explains Prof. Tarr. This is an evidence-based trend (Table 1) [6]. “Today, people treat for a shorter period of time than they did 10 or 20 years ago,” summarizes the infectiologist. For both pneumonia and cellulitis, it is recommended that antibiotic administration be limited to 5 days, and for pyelonephritis, 5-7 days [6]. Exceptions are possible, for example when dealing with severely immunosuppressed patients. Regarding the choice of the appropriate antibiotic, Prof. Tarr’s recommendations for indications are summarized in Table 2 [6].

Quinolone resistance in E. coli has been increasing for several years. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) recommends that quinolones no longer be used for mild or moderately severe infections, such as recurrent lower urinary tract infections (UTIs), if other recommended antibiotics can be used [11].

At both the individual and population level, there is a strong association between consumption and resistance [12]. In addition, quinolones cause more severe damage to the intestinal microbiome compared with other antibiotics, Prof. Tarr said. He said there is good data that with each microbiome damage induced by antibiotics, the defense function of the healthy microflora is weakened. And in recent years, numerous side effects of quinolones have become known.

Angina and uncomplicated cystitis: antibiotic-free therapy as an option

Using the example of a patient with uncomplicated cystitis, the speaker illustrated that in the absence of alarm signs (e.g., poor general health, elevated CRP), antibiotic-free therapy can often be an option. The decision should be made in the context of “shared decision making”, with patients being informed about the advantages and disadvantages. That cystitis develops into secondary pyelonephritis without antibiotic treatment is very rare, the speaker said. It affects at most 1:100 of affected women, he said. Regarding streptococcal angina, the guidelines officially allow for primarily antibiotic-free treatment since 2019 [13]. This does not mean that it always works. If fever and sore throat worsen after two to three days, delayed antibiotics may also be prescribed, he said.

In the pediatric field, the Association of Cantonal Physicians in Switzerland 2020 decided that children with streptococcal angina and scarlet fever are no longer excluded from attending kindergarten or school if they feel well [14].

Congress: Forum for Continuing Medical Education 17-20.11.2021

Literature:

- FOPH: Antibiotic Resistance Strategy Human Domain, www.bag.admin.ch/bag/de/home/strategie-und-politik/nationale-gesundheitsstrategien/strategie-antibiotikaresistenzen-schweiz.html (last accessed Dec. 21, 2021).

- ANRESIS, www.anresis.ch/de (last accessed Dec. 21, 2021).

- Renggli L, et al: Combating antibiotic resistance in Switzerland. Primary And Hospital Care – General Internal Medicine 2020; 20(11): 352-355.

- Knight GM, EL Budd, Lindsay JA: Large mobile genetic elements carrying resistance genes that do not confer a fitness burden in healthcare-associated meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Microbiology 2013; 159(Pt 8): 1661-1672.

- Landelle C, K Marimuthu, S Harbarth: Infection control measures to decrease the burden of antimicrobial resistance in the critical care setting. Curr Opin Crit Care 2014; 20(5): 499-506.

- Tarr P: Common infections and the most important antibiotics in practice. Prof. Philip Tarr, MD, Forum for Continuing Medical Education, Nov. 17, 2021

- Schwenke J, Schaub R, Tarr P: Antibiotic resistance update 2018 for the practice. Primary and Hospital Care 2018, DOI:10.4414/PHC-D.2018.01839.

- Global Antibiotic Research & Development Partnership (GARDP), https://gardp.org/uploads/2020/05/GARDP-brochure-2020-de.pdf (last accessed 12/21-21).

- ESCMID, www.escmid.org (last accessed 12/21-21).

- Swiss Society for Infectious Diseases, https://ssi.guidelines.ch, (last accessed 12/21/21).

- European Medicines Agency (EMA), www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/press-release/fluoroquinolone-quinolone-antibiotics-prac-recommends-restrictions-use_en.pdf, (last accessed 12/21/21).

- Gasser M, Schrenzel J, Kronenberg A: “Current trends in antibiotic resistance in Switzerland,” Swiss Med Forum 2018; 18(46): 943-949. https://medicalforum.ch/de/detail/doi/smf.2018.03404 (last accessed 12/21-21)

- Swiss Society for Infectious Diseases, Pharyngitis Guidelines, https://ssi.guidelines.ch/guideline/2408, (last accessed 12/21-21).

- Association of Cantonal Physicians of Switzerland, www.vks-amcs.ch/fileadmin/docs/public/vks/Schulausschluss__def_20200505_d.pdf (last accessed 12/21/21).

- Llewelyn MJ, et al: The antibiotic course has had its day. BMJ 2017 Jul 26; 358:j3418.

- World Health Organization (WHO), www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/antibiotic-resistance (last accessed 12/21/21).

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2022; 17(1): 44-45