Cough in a child usually has a harmless cause, but can be very stressful for the patient and the whole family. If the cough occurs as the sole symptom, asthma is unlikely to be a diagnosis. To evaluate for a chronic cough, the primary steps are a chest x-ray and spirometry (in children older than five years).

Coughing is a physiological reflex with the aim of clearing the mucous membranes of the respiratory tract of foreign bodies or accumulations of mucus. In this sense, the cough is on the one hand a sign of pathology in the respiratory tract, but on the other hand it is also an important mechanism of defense. This duality is crucial for deciding the right therapy.

If the cough is a disruptive factor leading to insomnia and thus fatigue, and if it maintains the mucosal lesion in a vicious circle of inflammation and repair, antitussive therapy is indicated. However, if cough is an important factor in mobilizing secretions, protussive therapy is indicated. This article is limited to the much more common issue of antitussive therapy in daily practice.

Cough in children: disturbing and alarming

Cough is one of the most common symptoms of consultations in general medical and pediatric practice. Parents present their child mainly for three reasons: First, usually the whole family suffers from insomnia and irritability due to the disturbing cough; second, the attacks are often very impressive, especially in young children, and the parents fear that their child may suffocate; third, especially in the case of a long-lasting cough, there is a fear that the child may suffer from a serious illness.

Asthma: often a misdiagnosis

The differential diagnosis of cough is broad, with acute cough being a viral infection or an acute noninfectious event, such as foreign body aspiration. When a cough persists for a long time, the attending physician still thinks predominantly of asthma or bronchial hyperreactivity, a common and popular, but unfortunately usually incorrect diagnosis.

Asthma presenting with cough alone and without expiratory whistling (wheezing and/or humming) and/or dyspnea is extremely rare. In other words, children with asthma may have a cough, but cough as the sole symptom leads to overdiagnosis of asthma. This finding is supported by several facts: Recurrent cough as a sole symptom is not clearly associated with bronchial hyperreactivity or atopy, cough without whistling is not affected by salbutamol or beclomethasone inhalations, i.e., antiasthmatic therapy, and there is no correlation between cough and asthma severity.

Classification according to duration and leading symptoms

For clinical understanding, cough is subdivided, either by duration (acute cough <2 weeks, subacute cough 2-4 weeks, chronic cough >4 weeks) or by specificity (specific or nonspecific cough).

- In specific cough, the cough characteristics indicate certain clinical pictures: staccato cough in chlamydial infections in infants, paroxysmal cough in pertussis and parapertussis, barking cough in viral laryngotracheitis or upper respiratory tract anomaly (tracheomalacia), honking cough with asymptomatic sleep in psychogenic cough.

- The non-specific cough is often classified according to its characteristics into a so-called dry cough (irritant cough) or a moist or wet cough (productive cough). This subdivision may be important for therapy, as a dry cough predominantly indicates mucosal damage with irritation of the cough receptors and a moist cough indicates an inflammatory, hypersecretory process.

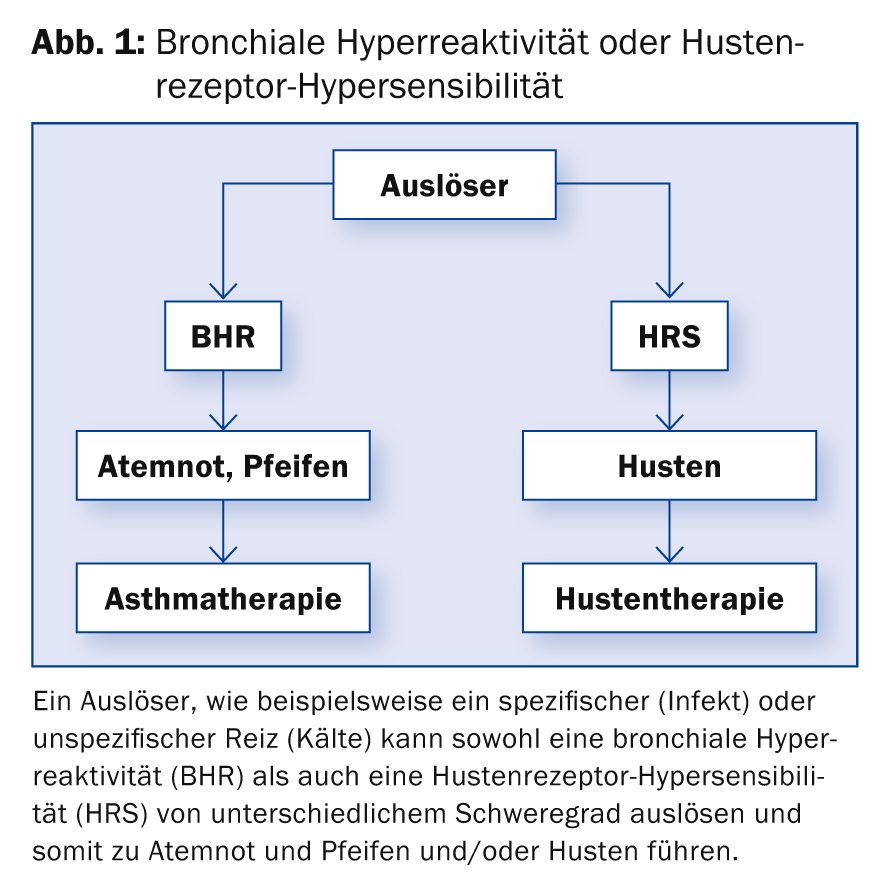

These definitions determine the further diagnostic and therapeutic procedure. Importantly, cough is not synonymous with bronchial hyperreactivity and therefore cough is often unresponsive to asthma therapy (Fig. 1).

Rather, there is damage to the mucosa and irritation of the cough receptors. Therefore, symptomatic therapy has the goal of mucosal repair and immobilization of peripheral cough receptors and the central cough center.

Medical history and physical examination

Important anamnestic questions arise:

- In addition to the cough, is there also a whistling (wheezing, humming)?

- If so, are the parents really describing a whistling sound or is it a non-specific sound?

- Are there signs of an upper respiratory problem (snoring, rhinitis, sinusitis)?

- Have the symptoms been present since birth?

- Did the symptoms start abruptly or are they chronic?

- Is there a predominantly productive cough (sputum)?

- Is the cough affected by food intake or is it position dependent?

- Are there other signs of chronic immunodeficiency?

- How is the cough during sleep?

Physical examination specifically looks for some points that are diagnostically helpful: Clock glass nails and at most already drumstick fingers, weight loss, failure to thrive, upper respiratory pathology, thoracic deformities (Harrison sulcus, barrel chest), fixed monophonic or asymmetric whistling, stridor, signs of cardiac or systemic disease.

The acute cough can usually be explained by an acute influence, primarily a viral infection or, depending on the history, a foreign body or toxic substance (inhalation, ingestion). Therefore, if the history and status are unremarkable, an adapted therapy and no further investigations are indicated for the time being.

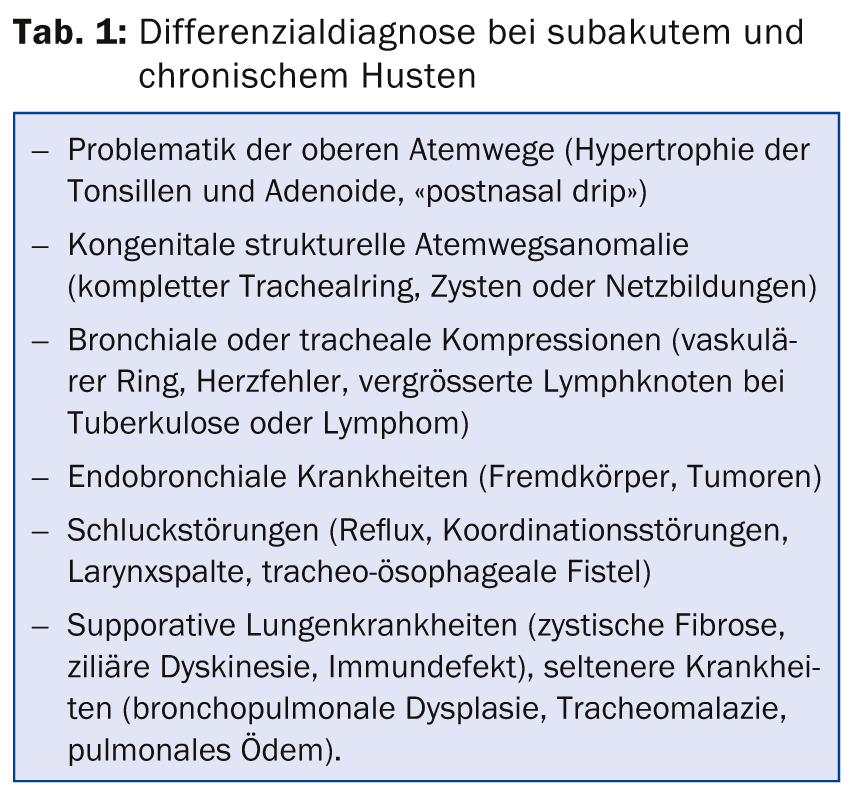

The clinical diagnosis in subacute and chronic cough is broader, although often, with an otherwise unremarkable history and status, it is a prolonged, either dry or wet postinfectious cough. In this case, it must also be connected to further resp. rarer diseases should be considered (Table 1).

Diagnostics for acute cough

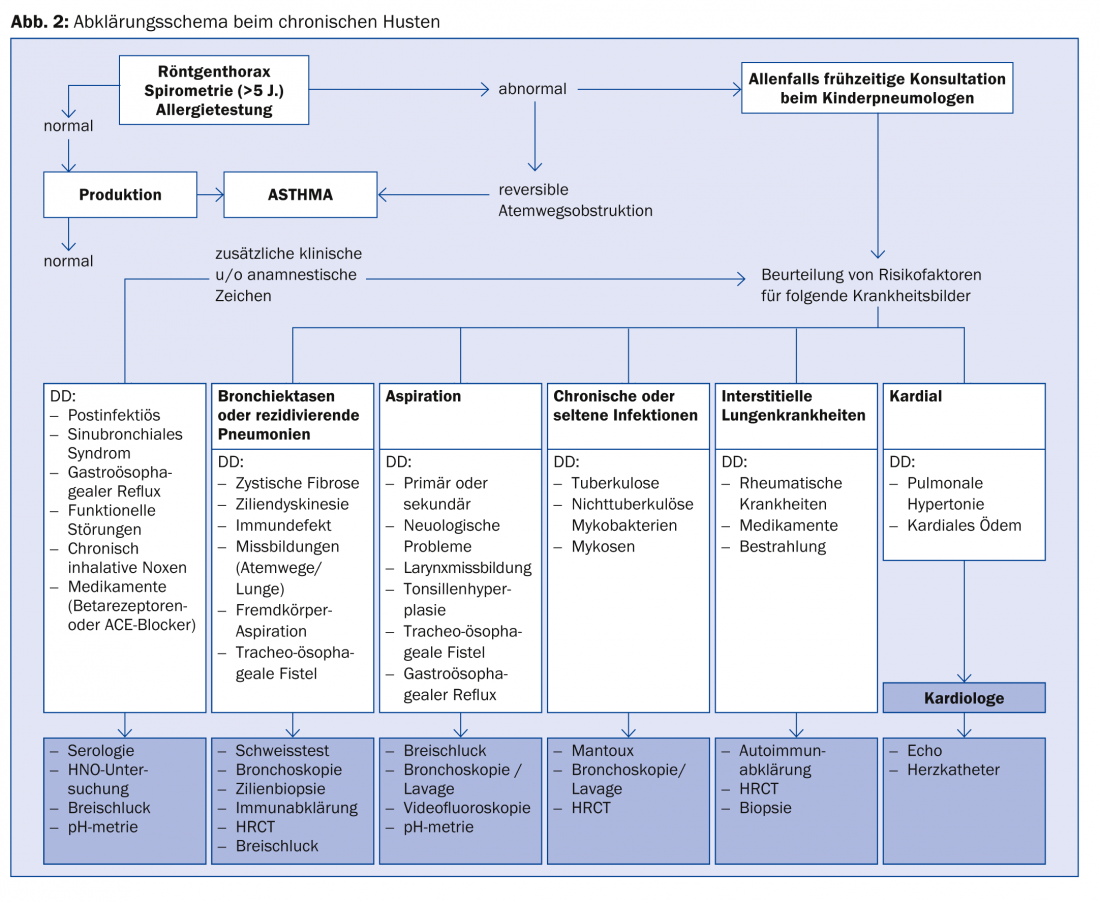

A work-up according to Figure 2 is recommended if the following signs are present anamnestically or clinically:

Failure to thrive, thoracic deformity, clock glass nails, hemoptysis, recurrent pneumonia, chronic respiratory distress, effort-dependent respiratory distress, pathologic auscultation findings, cardiac abnormalities, or immunodeficiency. In the absence of these signs, the question arises as to the characteristics of the cough (see Leading symptoms). In the absence of the above signs and a specific cough, it is useful to look for diagnostic signs of possible etiologies:

- Acute upper resp. lower respiratory tract infection: fever, rhinitis, sneezing, muscle pain, sore throat, tachypnea.

- Foreign body aspiration: aspiration followed by gagging, cough, +/- whistling breaths, stridor, tachypnea, cyanosis.

- Asthma: whistling breathing, dyspnea, atopy, response to bronchodilators.

- Inhalation injury: acute exposure to smoke or irritant gases.

- Embolism (rare!): Hypoxia, chest pain, known risk factors (coagulation disorder).

Diagnosis of subacute and chronic cough

The primary evaluation is as shown in Figure 2 with chest X-ray and spirometry (children >5 years). If one of these examinations is pathological, further clarification is performed. If both examinations are normal, it is possible to wait and observe, as the most likely diagnosis is a postinfectious cough or prolonged bronchitis.

The child should be given either intensive antitussive (dry cough) or anti-inflammatory (wet cough) therapy according to the nonspecific cough characteristics and reassessed in one week. In case of additional symptoms or increase of complaints, clarification should be made according to the scheme. In chronic cough, if the history and status are unremarkable, the focus is usually on a dry or wet postinfection cough. However, whenever possible, a chest x-ray and, if necessary, spirometry are indicated prior to trial therapy.

Causal or symptomatic therapy

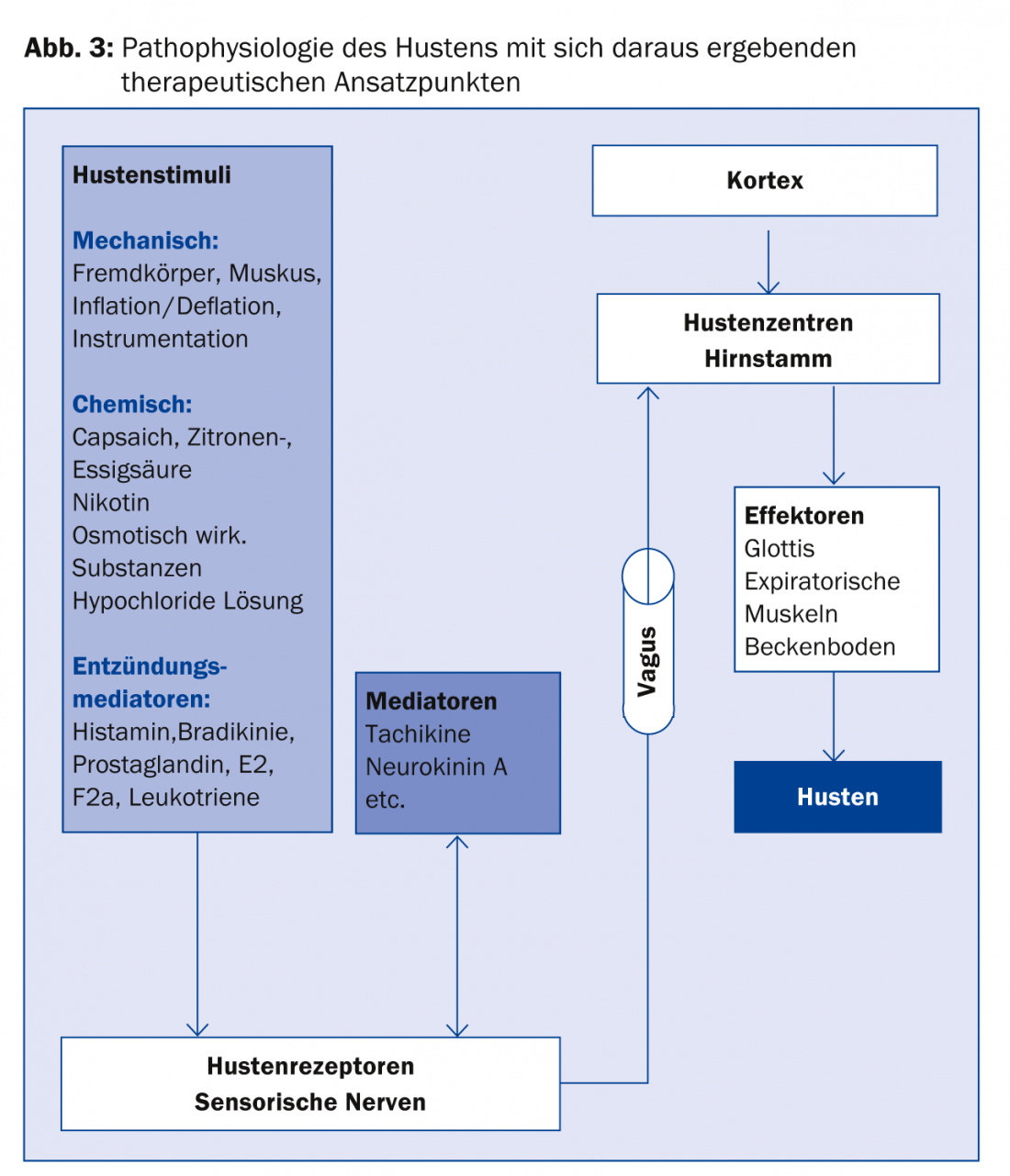

Causal therapy depends on the underlying diagnosis; treatment by the pediatric pulmonologist should be considered early. Symptomatic therapy for cough starts at different stages according to the pathophysiology of cough (Fig. 3).

As mentioned above, on the one hand, there is the possibility of treatment that controls or eliminates the cough as an annoying symptom (antitussive therapy); on the other hand, the cough can be supported as an important defense mechanism (protussive therapy). Protussive therapy is generally indicated only for bronchiectasis, cystic fibrosis, atelectasis, and pneumonia at most.

Antitussive therapy

Antitussive therapy is indicated for acute viral infections of the upper and lower respiratory tract and for subacute and chronic nonspecific postinfectious cough. Mainly medicinal measures are taken, but if possible stimuli such as passive smoking should also be avoided

be

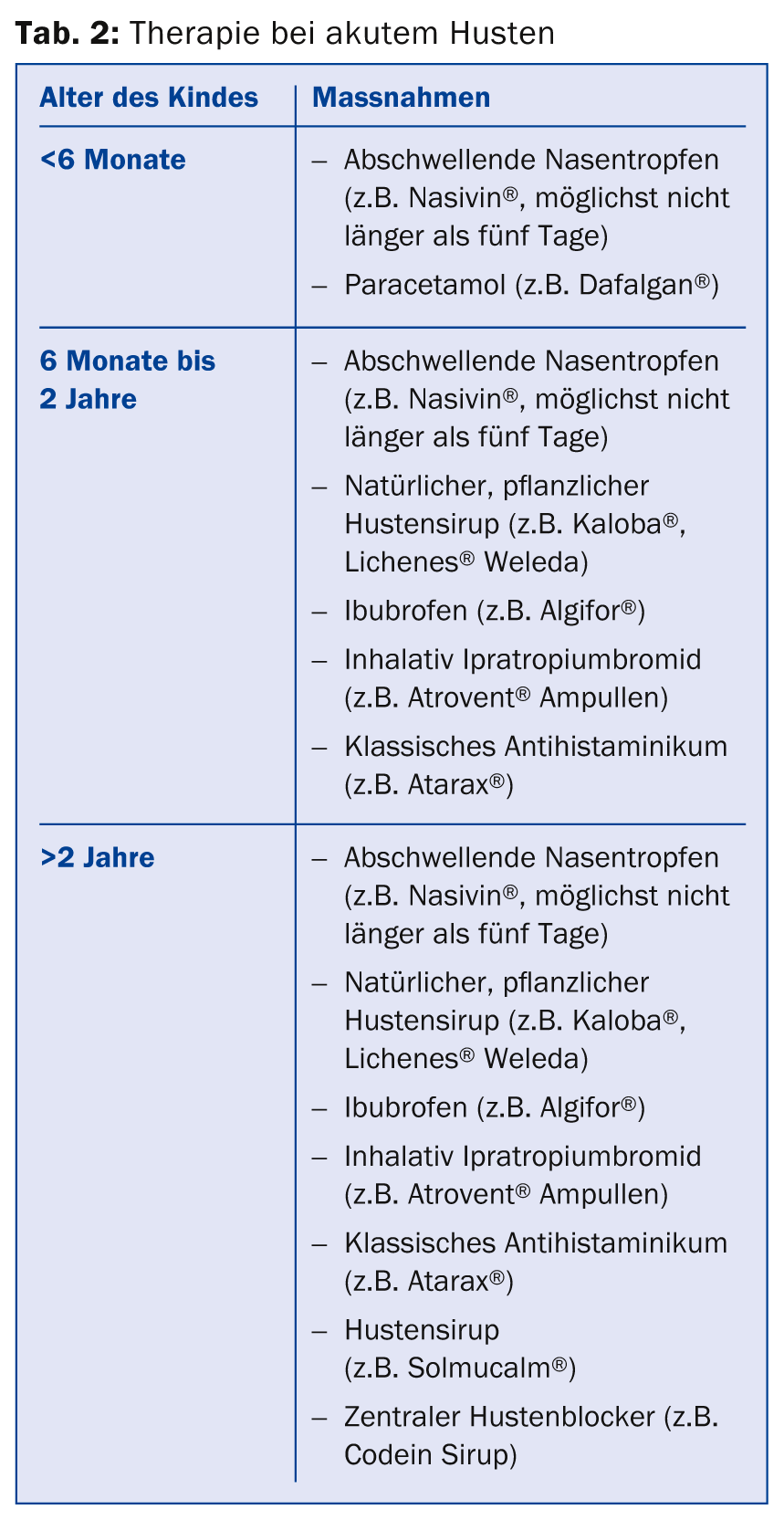

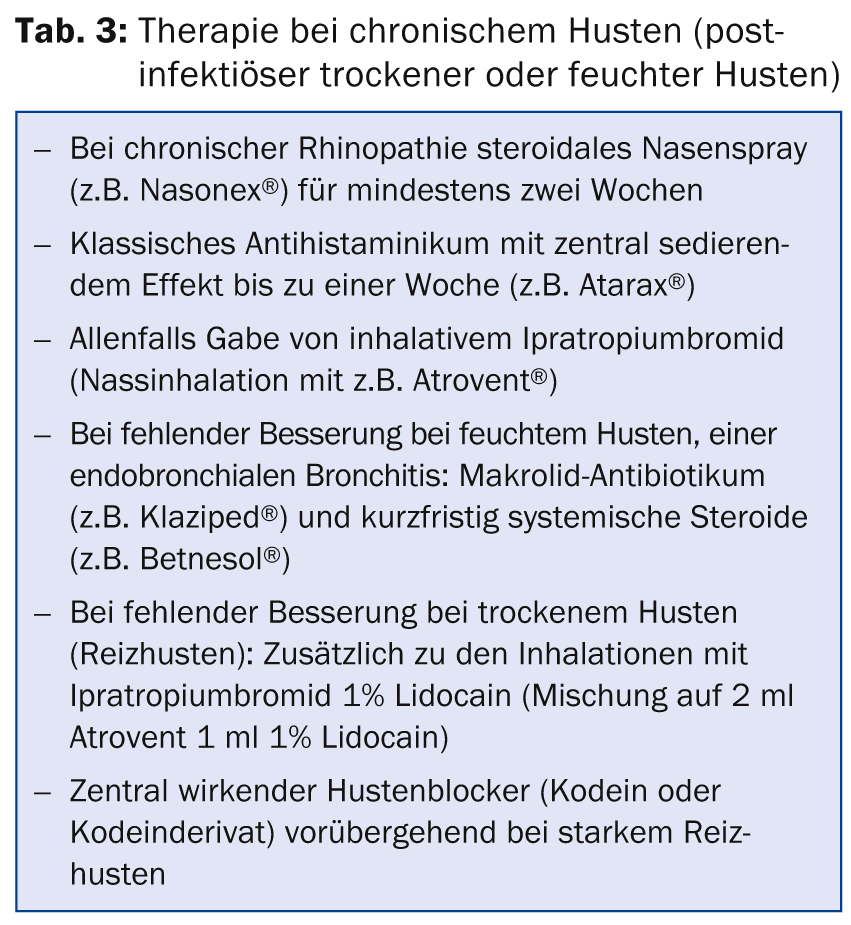

Although cough is so common, there is basically little evidence from studies; the younger the child, the less evidence. Therapeutic recommendations are therefore based predominantly on pathophysiological considerations and many years of experience. In symptomatic antitussive therapy, especially home remedies (e.g., honey) and herbal-based medications have proven to be well effective and tolerated. Different antitussive therapy is used depending on the age of the child (tables 2 and 3).

Conclusion for practice

- Always rule out an underlying disease requiring specific therapy before symptomatic cough therapy.

- Cough as the sole symptom argues against asthma.

- Symptomatic antitussive therapy is based on avoidance of the trigger, mucosal repair, peripheral immobilization of cough receptors, and central attenuation.

Further reading:

- Gruber W, Eber E, Zach M: How effective is symptomatic therapy of cough in common colds? Monatsschr Kinderheilkd 2000; 148: 156-164.

- Seidenberg J: Cough in childhood. Monatsschr Kinderheilkd 1993; 141: 893-906.

- Chang AB: Cough. Pediatr Clin N Am 2009; 56: 19-31.

- Rau M: Cough in specific medical conditions. Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine 2013(5); 13: 322-327.

- Nagel F, von Mutius E: Cough and asthma. Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine 2013; 13: 328-334.

- Irnstetter A, Griese M, Kappler M: Chronic productive cough in childhood. Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine 2013(5); 13: 335-341.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2015; 10(1): 44-46