The feet and therefore their skin and toenails are stressed every day. There is an interaction between the foot and the shoe. Wearing closed-toe shoes alone can contribute to the appearance of skin lesions and diseases. Malpositions can further accentuate this through uneven pressure distribution when walking, punctual pressure loads in the shoe and particularly narrow spaces between the toes. The therapy often requires an interdisciplinary thinking of the treating physician in the sense of a direct treatment of the skin change and a removal of the cause from an orthopedic point of view.

Since we always sweat in closed shoes, the skin is macerated more quickly, which can lead to mechanical deterioration and the occurrence of infections, especially keratoma sulcatum (Fig. 1), Gram-negative foot infections and mycoses. Even though modern materials, especially of sports shoes, are supposed to wick sweat away from the skin, leather as a natural material is often most suitable as a shoe material in everyday life. Regardless of its ability to absorb sweat, a worn shoe should dry for one to two days before being worn again.

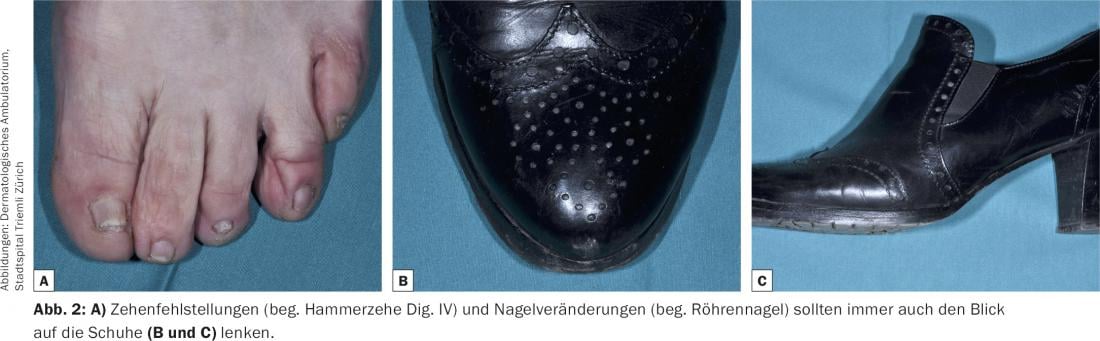

Narrow, pointed shoes and high heels, for their part, contribute to mechanical stress and, in the course of time, to the development of secondary deformities (Fig. 2). However, not only women or men with – depending on the respective fashion – very pointed shoes are at risk in this respect, but also wearers of quite ordinary ready-made footwear. The physiological hallux valgus angle is usually less than 15°. However, ready-made shoes often already have inner foot rim angles of 15-20°, which means that the medial side of the first ray is exposed to increased pressure and is pushed further and further into a valgus position as it progresses. Finding a balance between fashion demands and foot orthopedic health is difficult for the patient and especially for the consultant.

Acute and chronic sequelae

Acute and chronic skin lesions may result. Mechanically, bullae at pressure points and, at most, hematomas at heels (“black heel”) and toes (“runners toe”) are observed in poorly fitting shoes (Fig. 3) . Chronic mechanical stress physiologically leads to a thickening of the horny layer. Depending on the degree and extent of stress, this can lead to callus formation or clavi (corns). The latter in particular are caused by punctate pressure loads (Fig. 4) . Clavi are often misdiagnosed as verrucae plantares, although the two diagnoses can be well differentiated clinically. When the keratosis is removed with a scalpel blade, a homogeneous glassy keratosis is seen in clavus, whereas black stipples corresponding to capillary thrombosis due to neovascularization are seen in verruca. Unlike the clavus, the verruca interrupts the regular pattern of dermatoglyphs.

Hyperkeratosis can also occur between the toes as a result of increased pressure. Since this is soft due to the increased maceration there, it is also referred to as a heloma molle. Finally, a pressure ulcer (malum perforans) may occur if there is a predisposition such as polyneuropathy (diabetes mellitus!).

Common to all pressure-related skin changes is the fact that topical dermatological therapy is only supportive. First and foremost, the local pressure loads, including those caused by incorrect footwear and malpositions, must be analyzed.

Hallux valgus

A frequently observed deformity is hallux valgus, accompanied by a splay foot and the formation of hammertoes. In addition to unsuitable footwear (with a hard sole and lateral constriction of the foot), genetic factors as well as comorbidities (e.g. obesity) also seem to be possible causes.

As a result, pressure-related skin changes occur in the area of the pseudoexostosis at the base of the big toe (Fig. 5), in the area of the interphalangeal joints dorsally due to the hammertoe malposition of the toes, and very often in the area of the metatarsal II/III heads plantar due to the resulting splayfoot. The latter in particular is often accompanied by painful callus formation (so-called. Transfer metatarsalgia, Fig. 6) and may be misdiagnosed as clavus.

Diagnostically, a foot pressure measurement or gait analysis with and without footwear should be performed by the orthopedic technician in any case or, if necessary, an orthopedist should be consulted in the course.

Fighting the causes comes first

In order to eliminate the cause of the incorrect loading and thus the cause of the skin changes, all conservative therapy options should first be exhausted. In addition to wearing adequate footwear, orthopedic inserts, night positioning splints, or even special shoes should be discussed, among other options. Surgical intervention should be considered ultima ratio.

Nail changes

Subungual hematomas may also be observed on the nails, or transverse grooves, trachyonychia, or dystrophy may be observed with chronic pressure. In maximum consequence, complete nail loss may occur, with the risk of retronychia if the nail has not yet fallen out but is completely onycholytic with further pressure from the shoe. Unguis incarnatus is usually caused by a disproportion between the width of the nail insertion and the available width of the nail bed. Chronic pressure can accentuate this imbalance as a result of additional narrowing of the nail bed. Tubular nails (“pincer nails”) may also be contributed by the gait with less stress on the big toe.

Exostoses or bone sequestra (after fractures) press against the nail from below, causing deformation. Therefore, before a biopsy is performed for a suspected subungual tumor, an x-ray examination should always be performed to exclude osseous causes.

Further reading:

- Singh D, Bentley G, Trevino SG: Callosities, corns, and calluses. BMJ 1996; 312: 1403-1406.

- Freeman DB: Corns and calluses resulting from mechanical hyperkeratosis. Am Fam Physician 2002; 65: 2277-2280.

- Coughlin MJ: Common causes of pain in the forefoot in adults. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2000; 82: 781-790.

- Kosaka M, et al: Morphologic study of normal, ingrown, and pincer nails. Dermatol Surg 2010; 36: 31-38.

- Sano H, Shionoya K, Ogawa R: Foot loading is different in people with and without pincer nails: a case control study. J Foot Ankle Res 2015; 8: 43.

DERMATOLOGY PRACTICE 2015; 26(1): 6-9