The early detection of Barrett’s esophagus is of great importance.

This is why reflux patients with alarm symptoms should be endoscoped at an early stage. In the presence of an endoscopically and histologically confirmed Barrett’s esophagus, guidelines recommend regular monitoring depending on the risk profile (especially Barrett’s length) and the patient’s symptoms. Special attention must be paid to quality standards for control endoscopies, according to a recent analysis of registry data.

Barrett’s esophagus (box) is currently the only detectable precursor lesion for esophageal adenocarcinomas. The progression rates are given as approximately 0.1-0.4% per year [1–3]. In recent decades, a general increase in the incidence of adenocarcinomas has been recorded in Europe, North America and Australia, and the proportion of adenocarcinomas that occur predominantly at the junction with the stomach has also risen [19]. As the prognosis of esophageal adenocarcinomas is strongly related to the stage at diagnosis, screening of high-risk individuals is recommended and patients diagnosed with Barrett’s esophagus should be monitored regularly [4–6]. Data analyses show that most esophageal adenocarcinomas occur at an advanced stage with a worryingly low 5-year survival rate [7]. Against this background, the question arises as to whether there is room for improvement in current screening and monitoring strategies.

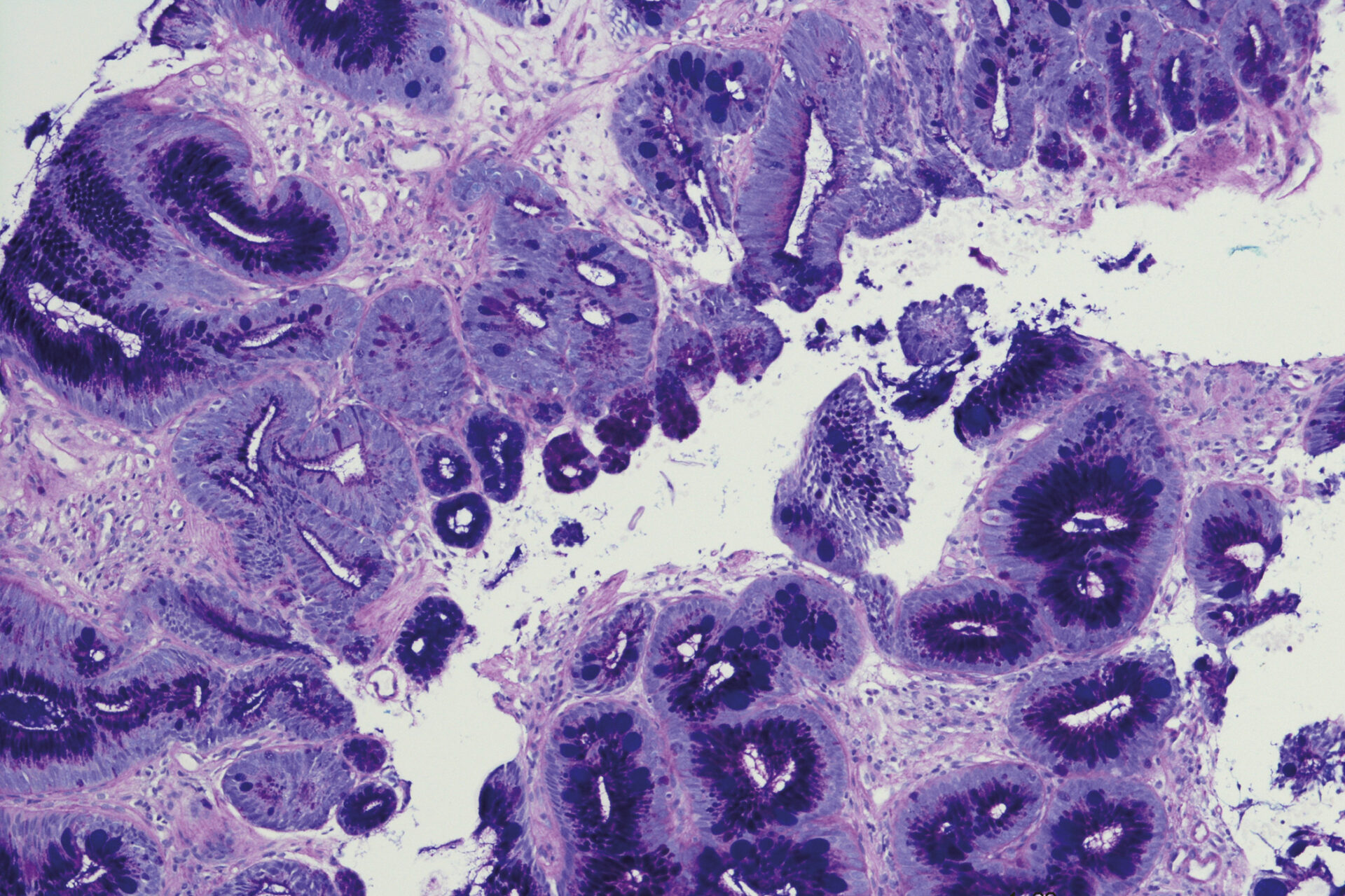

| In Barrett’s esophagus, the normal squamous epithelium of the esophagus is replaced by thin intestine-like surface tissue. This intestinal change, also known as Barrett’s metaplasia, can be a precancerous condition for Barrett’s carcinoma. Risk factors for the development of Barrett’s esophagus include a positive family history, male gender, smoking and obesity, as well as long-term reflux disease. The incidence of Barrett’s esophagus increases with age and men are two to three times more likely to be affected than women. |

Post-endoscopic adenocarcinomas

In a population-based study with a total of 73,335 reflux patients, 5.6% of those examined had Barrett’s esophagus [8]. The current reflux guideline of the German Society for Gastroenterology, Digestive and Metabolic Diseases (DGVS) recommends endoscopy for reflux patients with the following alarm symptoms: Dysphagia, odynophagia, gastrointestinal bleeding, unintentional weight loss, recurrent vomiting, positive family history for GI tumors [9]. As there was increasing evidence in the specialist literature of Barrett’s esophagus-associated high-grade dysplasia (HGD) and esophageal adenocarcinoma occurring after a negative endoscopy result, an international panel of experts introduced the terms post-endoscopic adenocarcinoma (PEEC) and post-endoscopic esophageal neoplasia (PEEN) [10]. Recent meta-analyses and cohort studies suggest that a high proportion of high-grade dysplasia and esophageal adenocarcinoma associated with Barrett’s esophagus are detected within the first year after endoscopy at which Barrett’s esophagus was diagnosed [11,12].

Large-scale register study

This observation was confirmed in the population-based cohort study Nordic Barrett’s Esophagus Study (NordBEST), reported Dr. med. Franz Ludwig Dumoulin, Chief Physician Internal Medicine, Community Hospital Bonn [20]. The NordBEST study included 20,588 patients with a first diagnosis of Barrett’s esophagus [13]. The average age of the participants was 64.6 years, 32.8% were women, and the median follow-up time was 4.5 years (interquartile range, 2.1-7.7; maximum follow-up time 14.9 years). The primary endpoints were rates of PEEC and PEEN. PEEC was defined as esophageal adenocarcinoma detected within 30 to 365 days of the index endoscopy at which Barrett’s esophagus was diagnosed, and PEEN was defined as high-grade dysplasia (HGD) or esophageal adenocarcinoma detected 30 to 365 days after the index endoscopy.

The overall documented 1-year incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma was 1.4%, which is largely consistent with epidemiologic data in the literature (Table 1). A time trend analysis revealed that among patients with a first diagnosis of Barrett’s esophagus, almost a quarter of all esophageal adenocarcinomas were discovered within one year of a supposedly negative endoscopy. The time trend analysis of the incidence rates (IR) over the three calendar periods (2006-2010, 2011-2015 and 2016-2020) showed an increasing incidence of PEEC (p=0.002) with unchanged incidence rates for incidences of esophageal adenocarcinoma (p=0.09). Similar results were found when evaluating the incidence rate ratios ( IRR) of PEEC compared to incisional esophageal adenocarcinomas. Older age and male gender were associated with PEEC.

The authors suggest that most cases of PEEC/PEEN are due to overlooked high-grade dysplasia and esophageal adenocarcinomas, but point out that rapid progression of carcinomas due to accelerated neoplasia pathways is also a possible explanation [14,15]. Factors contributing to missed lesions at endoscopy include lack of adherence to the Seattle biopsy protocol, limited mucosal sampling, inadequate inspection time of the esophageal barette segment, and inadequacy in recognizing subtle findings of early neoplasia [16–18]. The Seattle biopsy protocol involves taking 4-quadrant biopsies at 1 to 2 cm intervals [21].

Congress: Internists Update

Literature:

- Hvid-Jensen F, et al: Incidence of adenocarcinoma among patients with Barrett’s esophagus. NEJM 2011; 365(15): 1375.

- Codipilly DC, et al: The Effect of Endoscopic Surveillance in Patients With Barrett’s Esophagus: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 2018; 154(8): 2068-2086.e5.

- Harris E: Most People With GERD Don’t Have Increased Esophageal Cancer Risk. Published online September 27, 2023. doi: 10.1001/jama.2023.18744.

- Shaheen NJ, et al: Diagnosis and management of Barrett’s esophagus: an updated ACG guideline. Am J Gastroenterol 2022; 117: 559-587.

- Codipilly DC, et al: The effect of endoscopic surveillance in patients with Barrett’s esophagus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 2018; 154: 2068-2086.e5

- Qumseya B, et al: ASGE guideline on screening and surveillance of Barrett’s esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc 2019; 90: 335-359.e2

- Thrift AP: Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma: how common are they really? Dig Dis Sci 2018; 63: 1988-1996.

- Lin EC, et al: Low Prevalence of Suspected Barrett’s Esophagus in Patients With Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease Without Alarm Symptoms. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2019; 17: 857-863.

- Madisch A, et al: S2k guideline Gastroesophageal reflux disease and eosinophilic esophagitis of the German Society of Gastroenterology, Digestive and Metabolic Diseases (DGVS), March 2023 – AWMF registry number: 021-013.

- Wani S, Gyawali CP, Katzka DA: AGA clinical practice update on reducing rates of post-endoscopy esophageal adenocarcinoma: commentary. Gastroenterology 2020; 159: 1533-1537.

- Sawas T, et al: Magnitude and time-trend analysis of postendoscopy esophageal adenocarcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022; 20: e31-e50.

- Vajravelu RK, et al: Characterization of prevalent, post-endoscopy, and incident esophageal cancer in the United States: a large retrospective cohort study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022; 20: 1739-1747.

- Wani S, et al: Magnitude and Time-Trends of Post-Endoscopy Esophageal Adenocarcinoma and Post-Endoscopy Esophageal Neoplasia in a Population-Based Cohort Study: The Nordic Barrett’s Esophagus Study. Gastroenterology 2023; 165(4): 909-919.e13.

- Sawas T, et al: Identification of prognostic phenotypes of esophageal adenocarcinoma in 2 independent cohorts. Gastroenterology 2018; 155: 1720-1728.e4

- Jammula S, et al: Identification of subtypes of Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma based on DNA methylation profiles and integration of transcriptome and genome data. Gastroenterology 2020; 158: 1682-1697.e1

- Qumseya B, et al: ASGE guideline on screening and surveillance of Barrett’s esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc 2019; 90: 335-359.e2

- Wani S, et al: Post-endoscopy esophageal neoplasia in Barrett’s esophagus: consensus statements from an international expert panel. Gastroenterology 2022; 162: 366-372.

- Wani S, et al: Endoscopists systematically undersample patients with long-segment Barrett’s esophagus: an analysis of biopsy sampling practices from a quality improvement registry. Gastrointest Endosc 2019; 90: 732-741.e3

- “Esophageal carcinoma”, www.onkopedia.com,(last accessed 04.01.2023).

- “Esophagus: Barrett’s metaplasia”, Dr. med. Franz Ludwig Dumoulin, DGIM-Internisten-Update-Seminar, 10-11.11.2023, Wiesbaden/Livestream.

- Shaheen NJ, et al: American College of Gastroenterology. ACG Clinical Guideline: Diagnosis and Management of Barrett’s Esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol 2016; 111: 30-50; quiz 51.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2024; 19(1): 16-17 (published on 18.1.24, ahead of print)