The option of sequential PET computed tomography (PET) scans opens up new possibilities in the treatment of Hodgkin lymphoma. Current standard therapy in low-risk patients consists of two cycles of ABVD and 20 Gy of radiation. PET-guided, radiotherapy-free primary therapy is also being tested. PET-guided therapeutic regimens are also becoming increasingly established in patients with intermediate-risk or advanced disease. Hope for improved survival rates also lies in new substances such as brentuximab vedotin or nivolumab.

Because of the uniqueness of biology and incidence, Hodgkin’s lymphoma remains the best characterized lymphoma entity. According to the Global Burden of Cancer Working Group, incidence decreased between 1990 and 2013. During the same period, the incidence of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma has increased significantly. This article focuses on treatment options in Hodgkin lymphoma.

Reduction of therapy intensity thanks to PET

Until recently, the plethora of studies focused on maximizing the therapeutic index of initial therapy. The focus was on achieving the highest possible rates of disease-free and overall survival. The option of sequential PET computed tomography (PET) scans opens up new possibilities. PET results have not only prognostic but increasingly predictive value. Interim PET can potentially reduce the total cytostatic dose and partially omit radiotherapy. What is quite new is that this is being done in part at the cost of lower initial therapy efficiency. In case of failure of the initial therapy, the effect of intensive salvage therapy is relied upon.

What is the opinion of patients? A colleague affected 50 years ago wrote: “I think most people will choose a greater certainty of cure over the uncertainty of future effects. If they live long enough to have sequelae, it may still seem like the right choice” [1]. Does this statement correspond to today’s reality? Not quite: more and more patients with early-stage germ cell tumors are now opting for a “wait and watch” approach. These patients accept a risk and, in the worst case, accept more intensive chemotherapy. Physician and patient must be absolutely convinced that the overall survival is identical with both therapy strategies.

The following discussion of treatment options in classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma is devoted to three patient groups: Low-risk patients, intermediate-risk patients, and patients with advanced disease. The treatment of nonclassical, CD20-positive, lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma leans toward the treatment of classical Hodgkin lymphoma, especially in the advanced stages. The 10-20 patients newly diagnosed with this condition each year in Switzerland should be presented at regional tumor conferences.

Low-risk Hodgkin’s lymphoma

For staging Hodgkin lymphoma, PET but not bone marrow examination is required according to the revised Ann Arbor system 2014 [2]. Low stages should have low blood sedimentation, no bulk (see section on intermediate risk for definition), a maximum of two lymph node stations, and no extranodal (E) lesions, according to the German Hodgkin Study Group (GHSG) guidelines used in Switzerland. The current standard therapy was established in the HD10 trial [3]. With two cycles of ABVD and 20 Gy of radiation, over 90% of patients are disease-free and over 95% survive after an observation period of five years. The long-term toxicity of this regimen is not yet known. In pediatric studies, 20 Gy also shows toxicity.

Radiation therapy-free primary therapy with mostly increased doses of chemotherapy has been tested for some time. The PET examination seems to bring a breakthrough here. The H10 study of the EORTC/Lysa and the RAPID study of the British [4] show the same picture. If a PET is ABVD negative after a few cycles, radiation can be omitted. In the RAPID trial, progression-free survival at three years was 95% in the radiotherapy group and 92% in the chemotherapy-only group. The H10 trial was stopped early after one year of observation due to a PFS difference of 97.3% vs. 94.7%. However, there was absolutely no difference in survival in either study. In the RAPID study, 25% of patients were PET positive. They received local radiotherapy and 88% were disease-free after five years.

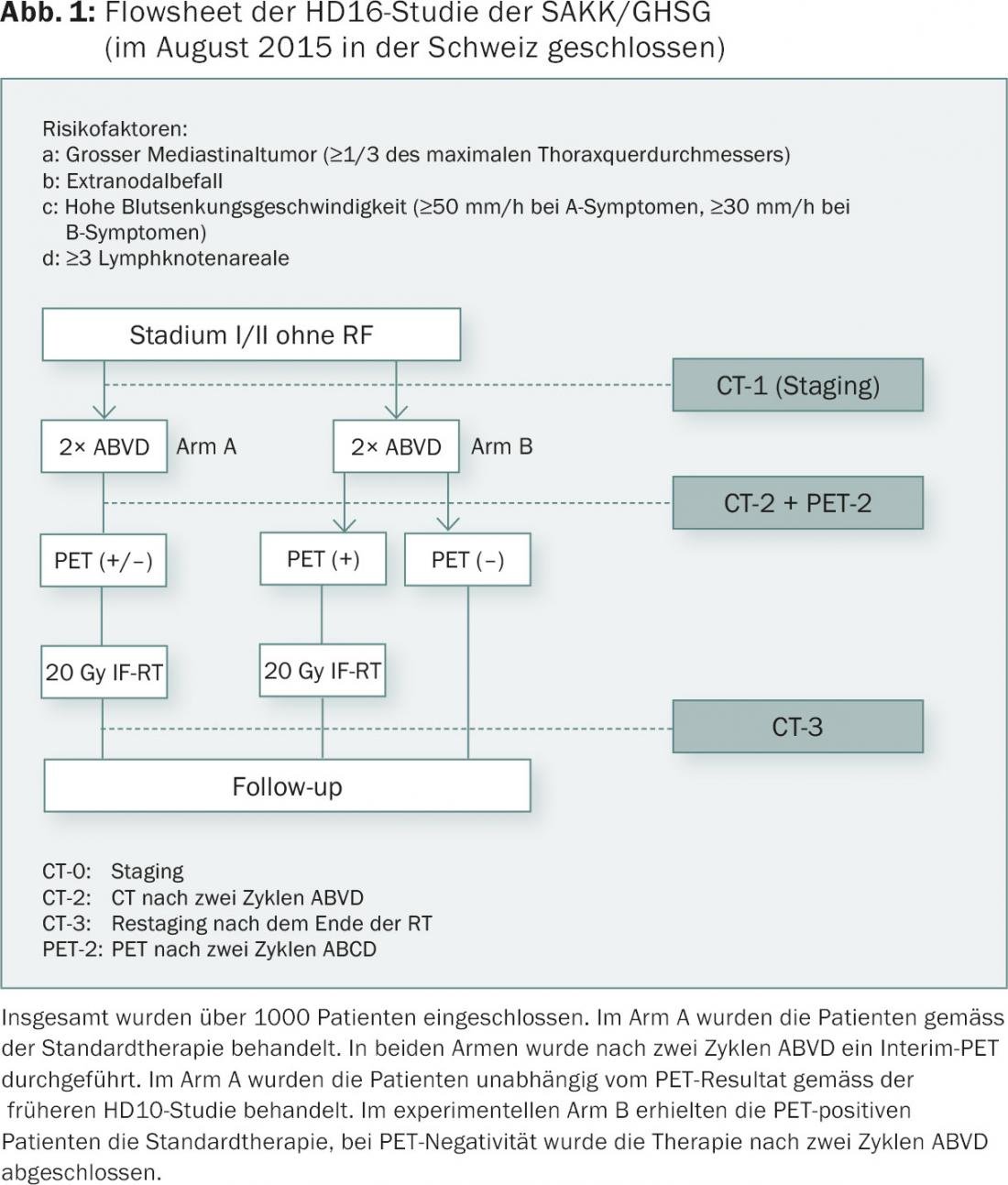

Should patients be offered this PET-guided therapy for low-risk Hodgkin lymphoma today? Isn’t the observation time much too short? How many cycles of chemotherapy are needed? Four, as suggested by the Vancouver group or the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN)? Three as in the RAPID study? Two as in the just completed HD16 study (Fig. 1) of the German Hodgkin Study Group (GHSG)? HD16 included over 1000 patients and was not stopped prematurely. So the two-cycle concept can’t be too far off the mark. Fact is, currently in North America, only half of low-risk Hodgkin’s patients receive radiation therapy!

What does PET-positive mean in interim PET?

The assessment of an interim PET must be performed according to the 5-point scale of the Deauville score. Score 1 and 2 are usually considered complete remission. In Hodgkin, this is independent of morphologic remission according to Barrington [5]. Deauville scores of 4 and 5 are considered insufficient remission. Each new lesion is considered a progression until proven otherwise. Rebiopsies are often necessary. A score of 3 is handled differently. In both the RAPID and H10 studies, a score of 3 was considered PET positive; in the RATHL study mentioned later, patients with a Deauville 3 were considered PET negative.

Intermediate risk Hodgkin’s lymphoma

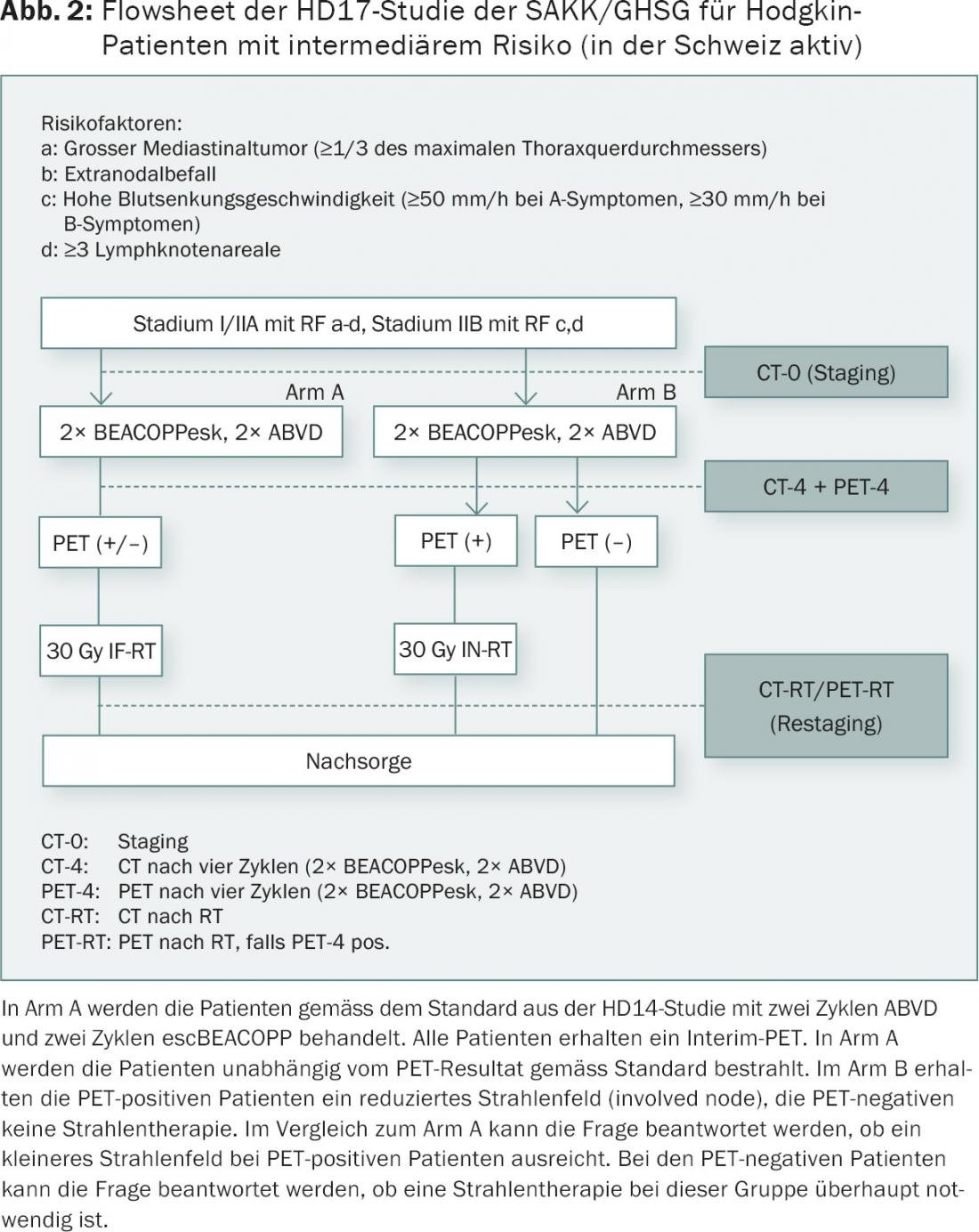

An intermediate risk is defined slightly differently. Basically, these are patients with locoregionally advanced disease but still confined to one side of the diaphragm. A bulk is common and is reported as >10 cm or greater than one-third of the transthoracic diameter according to the revised Ann Arbor criteria. A conventional chest radiograph is no longer required for this purpose. These criteria are in contrast to the definition of a bulk in the HD17 study of the SAKK/GHSG (Fig. 2). A bulk is specified here as >5 cm on CT, a mediastinal bulk as more than one-third of the thoracic diameter measured on a conventional chest radiograph.

The HD17 study will be conducted in intermediate stage patients (AA stage I, II with bulk, high subsidence, extranodal involvement, three or more lymph node stations). Tests will be conducted to determine whether radiation therapy can be omitted in negative PET and whether the radiation field can be reduced in PET-positive patients. The baseline chemotherapy regimen used is the 2+2 regimen (2 ABVD+2 escBEACOPP) according to the HD14 study of the GHSG. The use of the escBEACOPP regimen in this setting is controversial. However, fertility and secondary tumors are likely to be less of a problem compared with six cycles. In the EORTC H10 trial, intermediate-stage patients-40% with mediastinal bulk-were scheduled for PET after two cycles of ABVD. The PET-negative patients received an additional four cycles of ABVD, and the PET-positive patients received escBEACOPP twice and radiation. The study was terminated early due to predefined criteria. Solid results are not expected until 2016/17.

Advanced Hodgkin’s lymphoma

AA Stages III and IV are generally considered advanced. The GHSG also includes stages IIB with large mediastinum or E lesions here. The ABVD/escBEACOPP controversy has been discussed at length elsewhere. All randomized trials have shown significantly better disease-free survival, and the HD15 trial was arguably the best treatment outcome ever published in advanced Hodgkin lymphoma [6]. However, evidence of the survival advantage of escBEACOPP over ABVD was shown only indirectly in the HD9 trial or in a mathematical model in a Cochrane analysis.

With sequential PET, this discussion is becoming increasingly obsolete. Initial results from the HD15 trial established PET-guided radiotherapy with a PET scan at the end of chemotherapy. Overall, only 10% of all patients were still irradiated. Results from the UK RATHL study were shown at the 13th ICML Congress in Lugano in 2015. For the first time, meaningful interim PET data from a large phase III trial are available. A negative PET after two cycles of ABVD allows omission of bleomycin for the additional four cycles with significant reduction in bleomycin toxicity. It is debatable whether a disease-free survival of 84% at three years in PET negativity is a good benchmark. Thus, even with negative PET, almost one in six patients had to undergo a second therapy. In the HD15 study, which was non-PET-guided with respect to BEACOPP, only one in ten patients had received a second therapy after five years of observation. Several research groups are studying treatment escalation from ABVD to escBEACOPP in patients with positive interim PET. These data are not yet mature.

In the treatment of advanced Hodgkin’s lymphoma, we are currently in a dilemma in Switzerland. HD18 is closed. The new Hodgkin study (HD21) with implementation of brentuximab vedotin has been delayed until 2016. Viviani’s concept of generally performing ABVD-based therapy and treating all “failures” with high-dose salvage therapy, if possible, sounds tempting [7]. This would mean that at least 20% of patients would need to receive high-dose chemotherapy within five years of diagnosis. In reality, in these cases, one-third of patients choose not to receive high-dose chemotherapy, and the fact is that high-dose chemotherapy is curative in only half of the cases. Much hope lies in new substances such as Brentuximab Vedotin, Nivolumab etc.. A lot of patience is still required here.

Conclusion

In summary, all the evidence suggests that about 80% of Hodgkin’s patients face significantly less toxicity with mostly ABVD-based and PET-guided therapy compared with current standards. The remaining 20% will need more intensive therapies. Patients and clinicians will accept such a concept only if survival is maximally preserved.

Literature:

- Bishop G: PET-Directed Therapy for Hodgkin’s Lymphoma (correspondence). New Engl J Med 2015; 373: 392.

- Cheson BD, et al: Recommendations for initial evaluation, staging, and response assessment of Hodgkin and Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma: The Lugano Classification. J Clin Oncol 2014; 32: 3059-3067.

- Engert A, et al: Reduced treatment intensity in patients with early-stage Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med 2010; 363: 640-652.

- Radford J, et al: Results of a trial of PET-directed therapy for early-stage Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 1598-1607.

- Barrington SF, et al: Role of imaging in the staging and response assessment of lymphoma: Consensus of the international conference on malignant lymphomas imaging working group. J Clin Oncol 2014; 32: 3048-3058.

- Engert A, et al: Reduced-intensity chemotherapy and PET-guided radiotherapy in patients with advanced stage Hodgkin’s lymphoma (HD15 trial): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 non-inferiority trial.Lancet 2012; 379: 1791-1799.

- Viviani S, et al: ABVD versus BEACOPP for Hodgkin’s lymphoma when high-dose salvage is planned. Engl J Med 2011; 365: 203-212.

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2015; 14(5): 18-21.