It looks harmless, but it is cancer – a skin lymphoma. It develops when immune cells multiply uncontrollably in the skin, outside the lymph nodes. With one new case per 100,000 inhabitants per year, this form of skin cancer is relatively rare, but diagnosis is often not easy. Lymphomas are considered a chameleon in dermatology because they can look like other skin diseases.

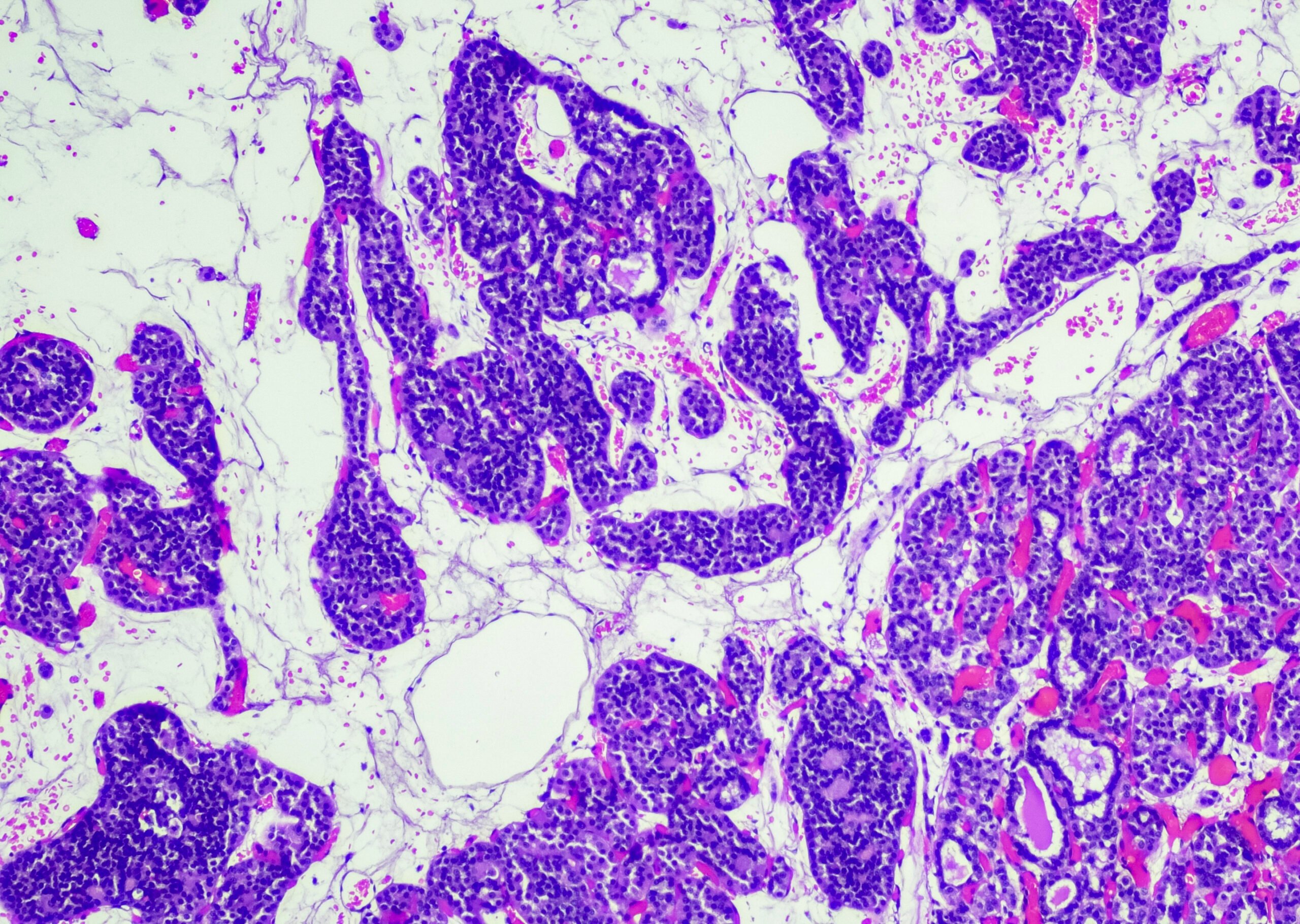

(red) In cutaneous lymphomas, uncontrolled immune cells multiply in the skin, usually starting from mature B or T cells. Cutaneous lymphomas comprise a broad spectrum of prognostically different subtypes, with T-cell lymphomas representing the most common subgroup. A careful clinicopathologic correlation is crucial for the final diagnosis. The most common skin lymphoma is mycosis fungoides, a cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Mycosis fungoides presents clinically with erythematous patches and plaques as well as tumors, the latter especially with prolonged persistence. Systemic dissemination to the blood, lymph nodes and internal organs is rare, but is associated with a significantly poorer prognosis.

While in the early stages of mycosis fungoides, skin-directed therapy measures are usually sufficient (topical steroids/topical chloromethine, light therapy) and the prognosis is good, in advanced stages and in Sézary syndrome (clinical features: erythroderma, lymphadenopathy and blood involvement), systemic therapies or multimodal (e.g. combination with radiotherapy or extracorporeal photopheresis) and interdisciplinary therapy concepts are indicated. System therapies for mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome include bexarotene and methotrexate or targeted therapy options such as brentuximab vedotin and mogamulizumab, in individual cases also bone marrow transplantation.

Cutaneous T-cell lymphomas also include indolent subtypes with mostly solitary skin manifestations such as CD4-positive lymphoproliferation or acral CD8-positive lymphoproliferation, as well as rare aggressive entities such as peripheral T-cell lymphoma or aggressive epidermotropic T-cell lymphoma. The latter is characterized by high disease dynamics with the rapid appearance of mostly multiple plaques/tumours, a limited response to therapy and a poor prognosis.

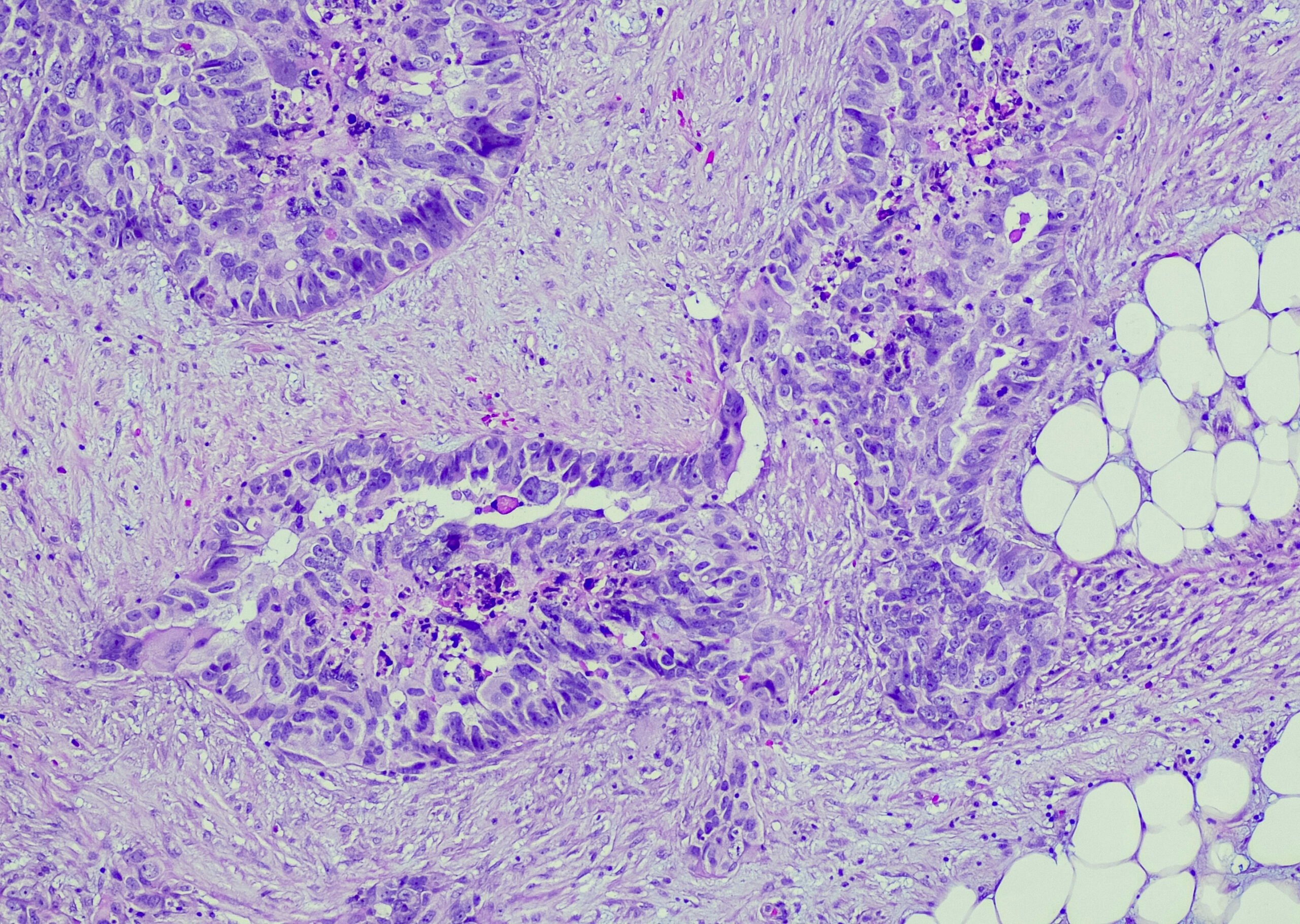

Cutaneous B-cell lymphomas are much rarer than cutaneous T-cell lymphomas. While the life expectancy of cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma and cutaneous follicular B-cell lymphoma (clinically slow-growing papules/tumors) is virtually unimpaired – despite frequent cutaneous recurrences during the course of the disease – cutaneous large B-cell lymphoma exhibits a more aggressive biological behavior (rapid appearance of large skin tumors) with an increased risk of systemic dissemination.

Conclusion: Cutaneous lymphomas comprise a broad spectrum of different entities with a highly variable clinical presentation on the skin organ and a subtype- and stage-dependent prognosis. The clinical-pathological correlation is decisive for the diagnosis.

Skin cancer is still the most common cancer with the highest rate of increase – despite the immense medical progress made in recent years. The number of new cases has doubled in the last ten years to around 308,800 per year. UV-related skin damage due to intensive sun exposure in childhood and adolescence is partly responsible for this. Every year, there are 160,700 new cases of basal cell carcinoma, 105,800 new cases of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and 42,300 new cases of melanoma.

Source: Prof. Dr. med. Marion Wobser, Department of Dermatology at the University Hospital of Würzburg, in the run-up to the German Skin Cancer Congress from September 25 to 28 in Würzburg (D), 26.09.2024.

InFo ONKOLOGIE & HÄMATOLOGIE 2024; 12(5): 20 (published on 24.10.24, ahead of print)