Depression not infrequently goes unrecognized in older patients because typical depressive symptoms take a back seat to physical symptoms. Depression is not a normal consequence of aging, but it can adversely affect and complicate it in a lasting way. Treatment of depression is also promising in seniors, but must carefully consider their particular vulnerabilities (cognitive performance, physical comorbidity, polypharmacy). For milder depression, psychotherapeutic interventions may be sufficient. For more severe depression, a combination with medication is usually indicated. For pharmacotherapy, SSRIs are the first choice. These – as well as other possible antidepressants – should be dosed according to the principle “start low, go slow” based on efficacy and tolerability. An effective antidepressant medication should be maintained at unchanged dosage for a longer period of time – several months – to avoid relapses.

Point prevalence for major depressive episodes in seniors varies from 5% to 10%, and for mild to moderate episodes from 5% to 35%. The great variability is due, among other things, to different populations. For example, the prevalence of depression is 10 to 20 times lower in independent seniors integrated in the community than in nursing homes [1]. Contributing to low prevalence rates may be the sometimes limited acceptance of the diagnosis and the apparent misunderstanding that depression is a normal consequence of aging.

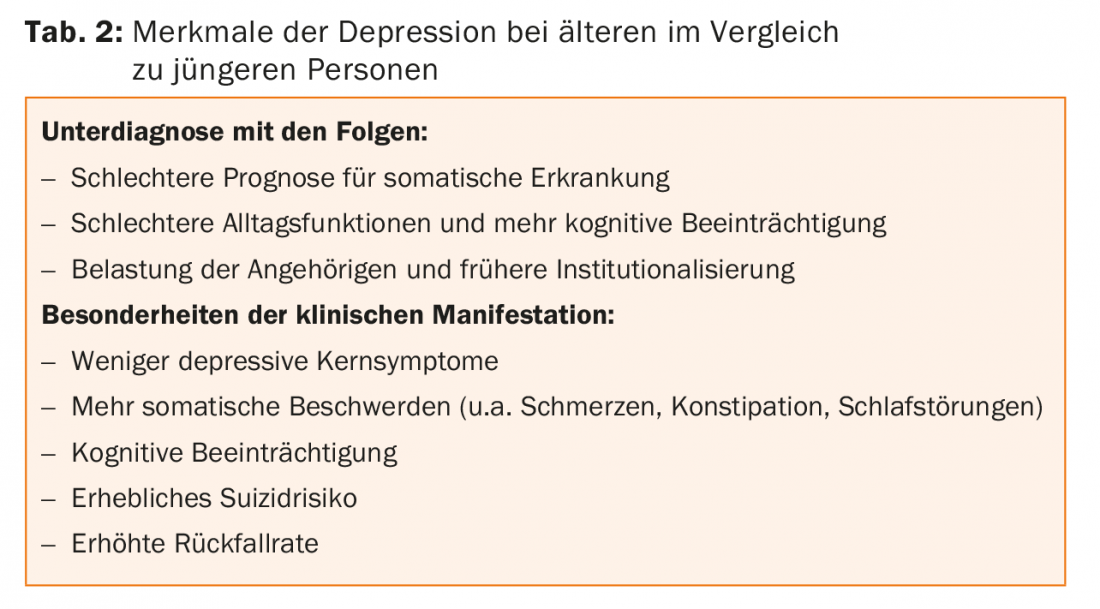

Compared with younger depressives, the main differences lie in the interaction between depression and the aging body, namely the accompanying somatic and psychological comorbidities or consequent polypharmacy. The age-associated biological, social and psychological factors influence diagnosis and therapy. Aging can be accompanied by drastic social changes, such as the loss of a spouse or a move due to illness. Such changes may promote the development of depression in vulnerable people.

Interactions between depression and somatic diseases

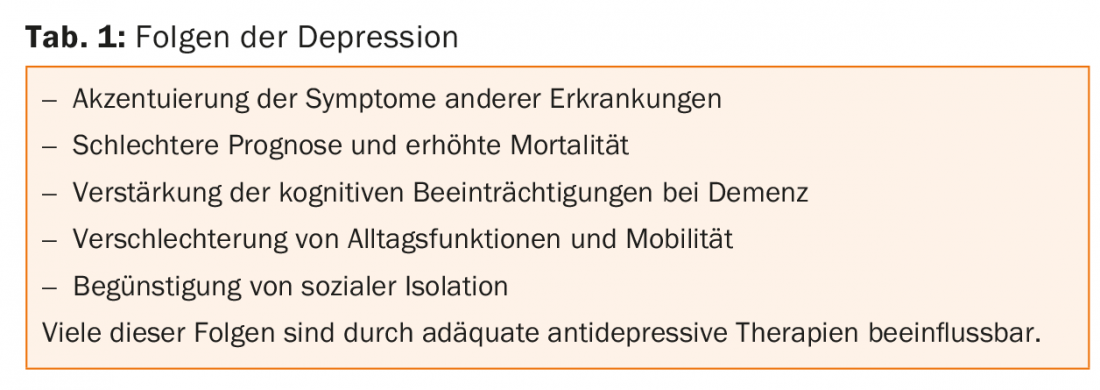

Depression can be both a risk factor for and a consequence of somatic illness. Such interactions impair prognosis and increase mortality from depression and physical illness (Table 1). These interactions exist, for example, between depression and chronic renal failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and cerebrovascular or cardiovascular disease [2]. Good antidepressant therapy can minimize unfavorable interactions.

The links between depression and dementia are many. There is evidence that depression earlier in life is a possible risk factor for age-associated dementia [3]. In addition, depression can be a prodrome of dementia, especially if the first depressive episode occurs after the age of 60. Finally, depression also occurs in the course of dementia, which can lead to additional losses in cognition or everyday functions. In dementia patients, the clinical distinction between depression and apathy is often difficult: sometimes only a pragmatic therapy attempt with an antidepressant helps here.

Cognitive impairment is found in 30-40% of seniors with depression. Attention deficits, impairments in processing speed and executive functions are typical. Severe executive dysfunction in the context of depression is often associated with a worse prognosis [4]. For the most part, the cognitive performance profiles of depressed individuals are not very informative when compared to the normal population because cognition is nonspecifically impaired. Many depressives have great difficulty staying motivated and focused during cognitive testing. They give up quickly in the test situation or they express themselves nihilistically. This must be taken into account when interpreting cognitive findings. However, a cognitive screening examination at the beginning of antidepressant therapy helps to assess progression and differentiate between depression and dementia.

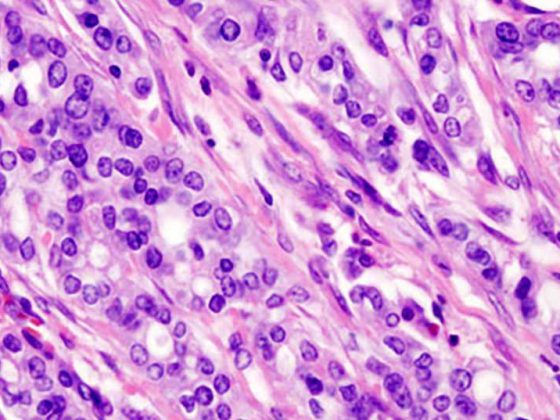

Pathophysiology of depression in older age.

Stress-associated disorders and their effects on the regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis also play a role in depression genesis in the elderly. In addition, functional and structural imaging reveals changes in the frontal brain and its connection to the limbic or striatal systems. These are typically atrophic changes in gray matter or microvascular changes in white matter, some of which correlate with the severity of clinical symptoms, e.g., severity of executive dysfunction [4]. The links between vascular changes and depression are complex and not conclusively understood.

Clinical presentation of depression in the elderly

The ICD-10 depression criteria do not take age into account. Older patients report less dejection and more frequently emphasize physical symptoms such as digestive complaints, pain, sleep disturbances or fatigability (table 2) . Others are conspicuous by surly, grumpy behavior. Cognitive impairment and agitated states are more common in seniors than in younger patients. Especially in elderly patients, depression is one of the suicide risk factors: suicide attempts are rather rare in seniors, whereas completed suicides are more frequent, especially in men. The physical and social changes can promote hopelessness and suicide [5].

Diagnostics

The anamnesis (possibly supplemented by an external anamnesis) is of particular importance in the diagnosis, with which the initial complaints, their development and the current complaints are inquired. The anamnesis enables the assessment of the course of the disease (unipolar vs. bipolar or first episode vs. recurrent course). In the medical history, risks, especially suicidality, medical and psychiatric comorbidities, substance abuse (benzodiazepines or alcohol), and current medication are asked.

The “15item Geriatric Depression Scale” can be used as a screening tool for depression [6]. Because many sufferers have diurnal variations, depression may be more difficult to grasp on exploration in the evening. Therefore, follow-up examinations are useful.

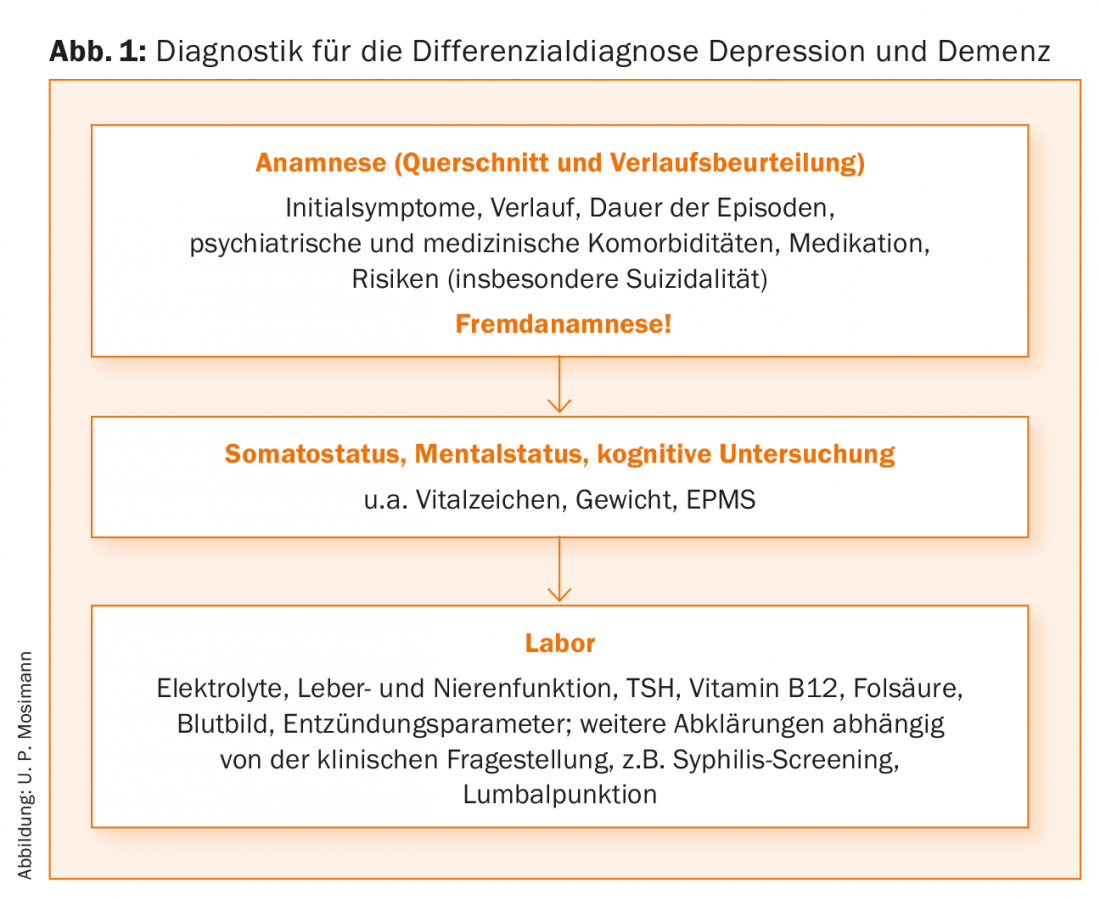

The medical history is supplemented by a somato- and psychostatus as well as a cognitive screening, e.g. with the Mini Mental Status (MMS) [7] or the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MOCA) [8]. The MMS is less effective at quantifying executive dysfunction than the MOCA. Laboratory tests help to identify somatic comorbidities (Fig. 1).

Principles of antidepressant treatment

The treatment of depression in seniors is too complex to be comprehensively recounted here. Currently, a group of experts in Switzerland is developing new evidence-based guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of depression in the elderly. At this point, only a few essential points in the treatment are summarized.

Even in seniors, the combination of psychopharmacological and psychotherapeutic therapy is of superior efficacy in the acute treatment of moderate to severe depression. For milder depression, psychotherapy may be superior to pharmacotherapy. With reference to age and cognitive impairment, psychotherapeutic interventions are used too cautiously, although methodological adaptations in this regard are quite available. Life review or problem-solving interventions have been shown to be effective in studies.

Antidepressants are effective in the elderly, although somewhat higher treatment resistance is to be expected. Medication management may be complicated by interactions with physical comorbidities, side effects, or drug-drug interactions resulting from polypharmacy or altered pharmacokinetics and dynamics. Before starting a new antidepressant therapy, the current medication should be carefully reviewed to minimize the number of medications and interactions and to rule out drug-caused depressive states.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) or antidepressants with dual (serotoninergic and noradrenergic) effects (SNRIs) are often used in acute treatment. Both groups are considered the first choice due to good tolerability. However, with noradrenergic substances, among other things, the possible increase in blood pressure must be taken into account as a side effect. It is possible that syndromes of inadequate ADH secretion (SIADH) and consequent electrolyte disturbances are more common in seniors than in younger patients. The classic tricyclic antidepressants are not first-line therapy because of anticholinergic side effects (micturition difficulties, constipation, orthostatic dysregulation, accentuation of cognitive deficits).

A common cause of lack of remission is reluctance to phase out antidepressant therapy. The recommended starting antidepressant dose for seniors is often lower than for younger patients (in the spirit of “start low, go slow”), but the dosage should be carefully increased if well tolerated and symptom persistent before alternatives such as switching, augmentation, or combination therapies are considered. The duration of antidepressant therapy cannot be determined at the beginning of therapy. If well tolerated, the antidepressant should be continued at unchanged dosage in remission (“the dose that gets you well, keeps you well”).

In seniors, the relapse rate is high and when the dose is reduced or the medication is stopped, the risk of relapse increases. Long-term studies indicate that maintenance therapies are effective for more than three years after remission [9].

Lithium prophylaxis is effective for bipolar disorder even in older age. Long-term studies show that bipolar disorder does not become asymptomatic with age. Unfortunately, recommendations on when to discontinue lithium prophylaxis in chronic renal failure are lacking. Some patients with bipolar disorder develop severe relapses after stopping prophylaxis, so a very careful risk-benefit analysis is appropriate when making this decision.

In a large study, no differences were found between verum and placebo treatment of dementia patients with depression with sertraline and mirtazapine [10]. However, it cannot be concluded from such results that depression should not be treated in the context of dementia, as studies show antidepressant effects with all treatments, and depression in dementia patients is associated with decreased quality of life or accentuation of impairment.

Literature:

- Chapman DP, Perry GS: Depression as a major component of public health for older adults. Prev Chronic Dis 2008; 5(1): 1-9.

- Teply RM, et al: Treatment of Depression in Patients with Concomitant Cardiac Disease. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2015 pii: S0033-0620(15)30022-0 [Epub ahead of print].

- Diniz BS, et al: Late-life depression and risk of vascular dementia and Alzheimer’s disease: systematic review and meta-analysis of community-based cohort studies. Br J Psychiatry 2013; 202(5): 329-335.

- Baldwin R, et al: Treatment response in late-onset depression: relationship to neuropsychological, neuroradiological and vascular risk factors. Psychol Med 2004; 34(1): 125-136.

- Minder J, Harbauer G: Suicide in old age. Swiss Archives of Neurology and Psychiatry 2015; 166(3): 67-77.

- Sheikh JI, Yesavage JA: Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS): recent evidence and development of a shorter version. In Clinical Gerontology: A Guide to Assessment and Intervention, ed. TL Brink, pp. 165-73. New York: The Haworth Press, 1986.

- Folstein MF, et al: Mini-Mental State (a practical method for grading the state of patients for the clinician). Journal of Psychiatric Research 1975; 12: 189-198.

- Nasreddine ZS, et al: The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: A brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. JAGS 2005; 53: 695-699.

- Reynolds CF 3rd, et al: Maintenance treatment of major depression in old age. N Engl J Med 2006; 354(11): 1130-1138.

- Banerjee S, et al: Sertraline or mirtazapine for depression in dementia (HTA-SADD): a randomised, multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2011; 378(9789): 403-411.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2016; 14(3). 28-30