The majority of skin cancers can be diagnosed and treated with simple biopsies and excisions in the office. An overview of biopsies, simple excisions, incision guidance, defect closure, flap plasty and skin grafting, mircrographically controlled excision with classic Mohs surgery or two-stage excision.

Due to the massive increase of skin cancer in our latitudes [1], dermatosurgery is also becoming increasingly important. A majority of skin cancers can be diagnosed and treated with simple biopsies and excisions in the office. Thus, these patients can be cared for at very low cost compared to treatment in the hospital, as long as simple dermatosurgical procedures are appropriately reimbursed by outpatient rates. Successful treatment of patients with skin cancer in the office includes mastery of simple surgical techniques as well as experience with other, non-surgical treatment procedures and knowledge of when referral for more involved procedures such as incision margin-controlled excision (Mohs surgery) is necessary.

Biopsies

Usually, if a skin tumor is suspected, a biopsy is performed first. For small tumors, the simplest approach is to perform an excisional biopsy; if malignant melanoma is suspected, total excision should be attempted whenever possible. Earlier concerns that incisional biopsy would promote possible metastasis have now not been confirmed in several studies [2], but complete excision of these lesions allows much more reliable histologic diagnosis and assessment of depth of invasion or tumor stage.

In cases of clinical suspicion of basal cell carcinoma or to differentiate actinic keratosis (precancerous lesion) from spinocellular carcinoma, a punch or shave biopsy is sufficient in most cases. Punch biopsy can be performed rapidly; for adequate histologic evaluation, the largest possible punch, but at least a 4-mm punch, should be used. The defects can be closed with single button sutures. As a time-saving trick, punch holes can also be closed with a single stitch that is doubled crosswise. It is important that the skin site where the punch biopsy is performed is drawn broadly, across the skin cleavage lines, resulting in an oval defect that is much easier to close.

For the histological diagnosis of an epithelial tumor, a shave biopsy is also sufficient in many cases. This can be done, for example, with a ring curette or with a flexible blade (Dermablade). Hemostasis is then performed with aluminum chloride solution 30% or with iron III solution. This technique is time-saving; however, care must be taken to obtain a sufficiently large biopsy specimen for histologic evaluation. Pigmented tumors and nevus cell nevi can in principle also be completely excised by means of shave excision, which gives even better cosmetic results in certain areas of the body (e.g. back). However, this technique should be reserved for physicians trained in it, otherwise there is a great risk that the lesion will not be removed in toto basally. On the one hand, this complicates the histological evaluation and, on the other hand, leads to recurrences which may be difficult to distinguish histologically from a pseudomelanoma.

Simple excisions

The majority of skin tumors can be treated curatively by simple excision with a safety margin. There is no consensus in the literature about the size of the necessary safety distances. This depends primarily on the type of tumor and its location. In the case of nodular basal cell carcinoma, a safety margin of 4 mm in healthy tissue is usually sufficient on all sides. For infiltrative growing tumors (e.g., cirrhotic basal cell carcinoma, micronodular basal cell carcinoma, etc.), the safety margin for 95% cure rates would need to be 13-15 mm [3]. In these cases, it is usually more advisable to perform micrographically controlled surgery. For spinocellular carcinoma, the lateral safety distance should be 6-10 mm, depending on the degree of differentiation [4]. Pigmented skin tumors should be totally excised with a close safety margin; if a malignant melanoma is then histologically revealed, further post-excision should be performed with 1-2 cm safety margin depending on the depth of penetration of the melanoma [5]. Even in cases of high clinical suspicion of malignant melanoma, excision should not be performed primarily with a safety margin, as this would make any sentinel lymph node biopsy impossible or more difficult and less precise.

Cutting

For spindle-shaped excisions, the incision should always be placed in the direction of the skin split lines. Different textbooks sometimes contain different schemes with these skin cleavage lines. It is therefore always advisable to check with the fingers in which direction the highest tension is present before injecting the local anesthetic. In case of doubt, it is advisable to excise the finding along its border and to add to a spindle-shaped defect only afterwards, when it becomes obvious in which direction the round excision will be elongated. In the vicinity of free edges (e.g. mouth, nostrils, eyelids) it is extremely important that the incision is made perpendicular to this free edge, otherwise it will be distorted, which would result in aesthetically very unfavorable results.

Defect closure

Defect closure is usually multilayered in spindle-shaped excisions. A subcutaneous suture is placed first, which strictly speaking is actually more of a subcutaneous/cutaneous suture and has as its main purpose to reduce tension. The selection of the appropriate suture material is important here – in areas where wide scars often result from skin tension, an absorbable suture with a long resorption time should be selected. This may allow the scar to be further along in the healing and maturation process until the subcutaneous suture no longer helps to reduce tension.

This is followed by fine adaptation of the wound edges with a cutaneous suture, which also serves to stop bleeding. For beautiful cosmetic results, it is crucial that the wound edges are precisely adapted with the cutaneous suture without steps and that the puncture is made close to the wound edge. In addition, in many areas of the body, more beautiful results are obtained when the wound edges are inverted during closure. On the one hand, this can be achieved by the correct positioning of the subcutaneous suture, on the other hand also by different suture techniques (e.g. Donati suture or mattress suture) (Fig.1). As healing progresses, each scar contracts, so a primarily flat wound closure often results in a retracted scar, while an inverted, primarily somewhat bulging wound closure ultimately results in a flat scar. If the wound is already closed without tension by the subcutaneous suture, the skin suture can be performed with a continuous suture in many cases. This technique is primarily time-saving and often gives nice cosmetic results, especially when the suture is placed intracutaneously. There are also continuous suture techniques that allow good hemostasis of the wound edges by looping the suture around the wound (Fig. 2). However, any complications (suture dehiscence, wound infections, postoperative bleeding) are more difficult to treat with continuous suture techniques, as the entire suture usually has to be opened.

Flap plastic surgery and skin grafts

If a defect can be closed by addition to a spindle-shaped defect and direct adaptation of the wound edges without distorting surrounding structures, this is the preferred method. Direct wound closure makes the treatment the fastest and most comfortable for the patient; it is the most cost-effective and usually gives the best aesthetic results. However, if defect closure is no longer possible due to the size of the defect or the aesthetic result, flap plasty or skin grafts are used. Many simple flap plasty procedures can certainly be performed in the office if the patient has the appropriate experience. These include defects in the area of the forehead, for example, which can be closed with an O-Z plasty or an O-T plasty. Or defects in the temporal region, which can be closed with rotational plasty or transpositional plasty. Full-thickness skin grafting can also be performed well in the office. In many localizations, a full-thickness skin graft gives a quite good aesthetic result, for example in the area of the tip of the nose or the temple. Full-thickness skin grafts usually become less beautiful in convex areas such as the cheek or forehead.

Micrographically controlled excision

For many tumors, it is more appropriate to treat them primarily with micrographically controlled surgery. On the one hand, classical Mohs surgery can be used for this. In this procedure, the tumor is excised, and immediately thereafter histologically processed by frozen section examination according to a special procedure in such a way that the entire lateral and deep incision margin can be histologically evaluated. Histological evaluation is performed by the dermatosurgeon himself, which allows the highest precision in the localization of any margin-forming tumor components, which in turn results in the smallest possible excision defects. However, this technique is reserved for specialized centers, which have the possibility of surgical treatment and histological examination under one roof.

On the other hand, there is the option of two-stage excision, in which the excisional defect is treated with a placeholder dressing while the excised tissue is processed by a dermatohistopathology laboratory under incision margin control. Re-excision or wound closure is performed a few days after this result is available. This technique should be reserved primarily for tumors that are difficult to evaluate histologically, for melanocytic tumors on the face, and in situations when referral to a center specializing in Mohs surgery is not possible.

Common to both methods of micrographically controlled excision is that complete examination of the entire incision margin can significantly reduce the tumor recurrence rate [7]. In nodular basal cell carcinoma, for example, cure rates of approximately 95% are found with simple excision with a 4-mm safety margin [7]. Incision margin-controlled surgery can increase this to 99% [7].

The difference is even more pronounced with regard to recurrence rates for recurrent tumors: Here, recurrences occur in up to 17% of cases with normal excision with a 4-5 mm safety margin, whereas these can be reduced to 3-4% with Mohs surgery [8]. At the same time, the use of incision margin-controlled surgery results in smaller excision defects because primarily smaller safety distances can be selected. This advantage comes into play especially in classic Mohs surgery, where the excisions can be assessed by the dermatosurgeon himself and the post-excisions can be made with corresponding precision.

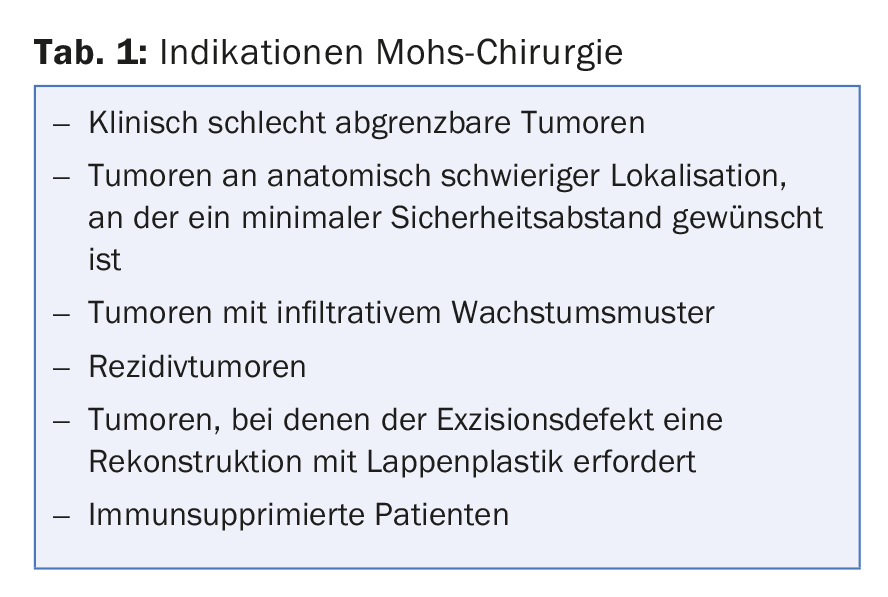

Because of the additional expense of incision margin-controlled surgery, it cannot be performed on every epithelial tumor. It should be used primarily when the difficult localization of the tumor or the need for reconstruction with a flapplasty necessitates the smallest possible but certainly tumor-free excision defect, in tumors that are clinically very difficult to delineate, or in tumors that show a particularly aggressive growth pattern or tend to recur more frequently (e.g., infiltrative basal cell carcinomas, perineural invasion, localization in the H zone of the face, diameter greater than 2 cm, etc., see Table 1). For such tumors, surgical treatment in the office is probably less appropriate and referral to a dermatosurgical center should be considered.

Literature list at the author

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2017; 27(4): 30-33