Continuous and effective pharmacotherapy is essential for patients with schizophrenia, as they are at high risk for developing a severe mental illness. But what constitutes successful medication therapy management? This is because the treatment situation is complex and multiple patients are not uncommon. In addition, undesirable effects place an additional burden on the adherence of the per se difficult clientele.

It is estimated that around 80,000 people in Switzerland suffer from schizophrenia. The probability of developing this disease is about 1% in the course of life. This makes schizophrenia one of the most common forms of non-organic psychosis [1]. The expression and severity of the complex disease vary greatly. However, there is a high risk of developing a serious mental illness. High-quality and continuous pharmacotherapy is therefore an obligatory prerequisite for most patients to achieve remission, relapse prevention, and lasting recovery, as reported by Prof. Martin Lambert, MD, Hamburg (DE). Pharmacotherapy for schizophrenia must be evidence-based according to guidelines. This increases the likelihood of achieving the effectiveness goals of pharmacotherapy.

A prerequisite for adequate treatment management is a long-term design with a combination of psychosocial therapy and pharmacotherapy. Attention must be paid to the often combined risk factors of genetics, dreams, and multimorbidity. However, the psychosocial burdens and consequences, the often severe and long episodes, complex treatment requirements, and high morbidity and mortality are also challenges that must be considered.

Addressing the acute phase of schizophrenia

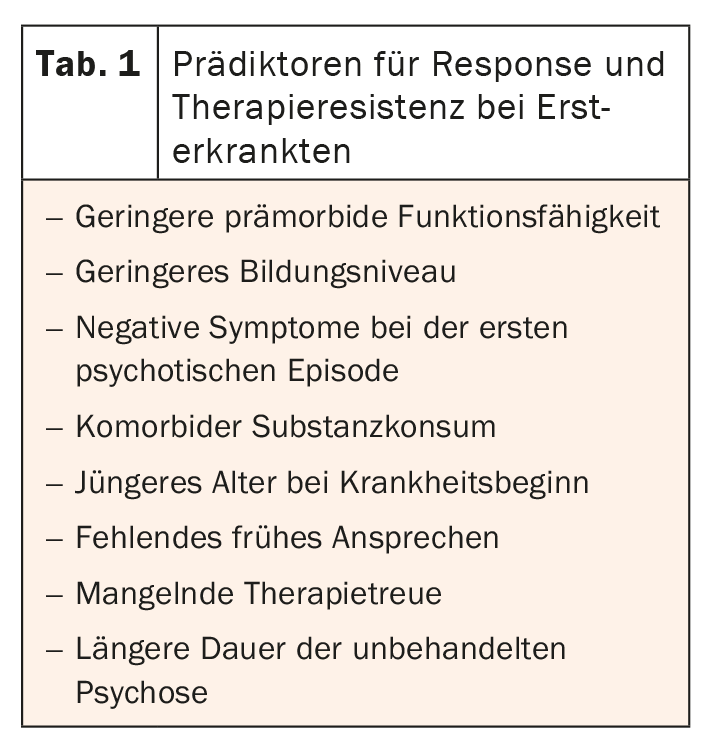

For treatment in the acute phase in first-episode patients, it has become apparent that 2nd-generation antipsychotics are preferable to those of the first generation. Moreover, they should be administered as monotherapy at a low dose [2]. The goal is to achieve remission with the lowest possible dosage. Furthermore, it should be noted that response rates in untreated sufferers are significantly better at 81.3% (≥20% PANSS) than in pretreated patients at 65.8%, according to the expert [3]. In addition, it is important to use predictors of response and treatment resistance to estimate the prognosis of treatment in order to be able to adapt therapy at an early stage if necessary ( Table 1) [4]. In general, it can be assumed that therapy management should be switched if response (≥20% PANSS) at optimal dose fails within two weeks, Lambert summarized. Antipsychotics are also the drugs of choice for multiple patients.

Because positive symptoms are so dominant in acute therapy, the frequency of negative symptoms is sometimes underestimated. In this context, 60% of patients show at least one negative symptom and in almost one-third these symptoms persist [5]. It is also frightening that 20% have deficit syndrome, the speaker underlined. In these cases, good pharmacotherapy is even more important. First-generation antipsychotics and stimulation procedures have not been shown to be effective. In contrast, second-generation antipsychotics, antidepressants, or combinations of these are well suited.

The long haul is what counts

Long-term therapy focuses on which treatment management is most appropriate for the patient. Choices include no therapy, intermittent therapy, or continuous antipsychotic therapy. Studies have demonstrated that continuous relapse prophylaxis is highly significantly superior to the other two measures [6]. In this regard, the affected person should be treated at a standard dosage, as low or very low dosages are associated with significantly higher relapse rates and discontinuation of therapy [7].

The biggest problem in long-term treatment is antipsychotic adherence. Meta-analyses show that nonadherence is the strongest predictor of relapse, increasing the likelihood by 400%, Lambert cautioned. This is because the consequences are manifold, including disease progression, worsening insight into the disease, symptom increase, reduced antipsychotic response, and increased risk of suicide.

Drug-induced side effects in view

But no effect without a side effect. Due to the high efficacy of antipsychotics, many adverse drug reactions must be considered. In principle, an optimal drug has a very low number needed to treat (NNT) and a very high number needed to harm (NNH). In clinical practice, however, things are often different. Unfortunately, the effectiveness often corresponds with undesirable side effects, Prof. Dr. med. Alkomiet Hasan, Augsburg (DE) pointed out. With respect to the endpoints of relapse prevention and reduction of psychotic symptoms, antipsychotics are highly effective preparations. Conversely, however, this also means that relevant side effects can occur. However, the expert also emphasized that the differences in efficacy between the individual preparations are significantly smaller than the differences in tolerability. Therefore, the goal should be individualized antipsychotic treatment based on side effects with the lowest possible dose.

In particular, side effects such as early dyskinesia, acute dystonia, or parkinsonoid are very distressing and occur predominantly with drugs with strong D2 blockade. Second-generation antipsychotics such as risperidone or amisulpride may also be affected. Preventively, a slow increase in dose or the use of alternative preparations can be considered. The patient should be explicitly asked about akathisia, which can generally occur with all antipsychotics. Here, too, as in all therapy management, a slow increase in dose is recommended. If needed, switch to another antipsychotic.

Even before starting antipsychotic treatment, people with schizophrenia are at increased risk for obesity and diabetes. As the disease progresses, this risk continues to increase and is a major factor in increased cardiovascular mortality. Basically, this is a multifactorial process. Still, preparations with antihistaminergic or antimuscarinic properties, for example, are among the high-risk drugs, Hasan said. Partial antagonists, for example, appear to be well suited here.

Congress: DGPPN

Literature:

- www.gesundheit.bs.ch/gesundheitsfoerderung/psychische-gesundheit/krankheitsbilder/psychose/schizophrenie.html (last accessed 03.03.2022)

- Zhang J, et al: Int J Neuropsychopharmacology 2013; 16: 1205-1218.

- Zhu, et al: Eur Neuropsychopharmacology 2017; 27: 835-844.

- Bozzatello, et al: Front Psychiatry 2019; 10: 67.

- Bobes, et al: J Clin Psychiatry 2011; 72(7): 1017.

- De Hert, et al: CNS Drugs 2015; 29(8): 637-658.

- Højlund M et al. Lancet Psychiatry 2021; 8(6): 471-486.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2022; 20(2): 24-25.