The most common infections affect the skin and genitourinary tract. Infections occur more frequently above an HbA1c >8.5%. SGLT2 inhibitors are effective in the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus, but good hygiene must be discussed with the patient before starting therapy. Diabetic foot can be prevented by regular foot inspection and good foot self-inspection instruction. Treatment is always interdisciplinary.

Diabetes mellitus is an increasingly common disease, which in its chronic course can lead to various complications if not adequately controlled.

Currently, we are experiencing a radical change in therapeutic options, and the topic of obesity and its consequences (including diabetes) is also widely discussed in the lay press.

This overview is intended to provide information on the current links between elevated blood glucose and the risk of infectious diseases.

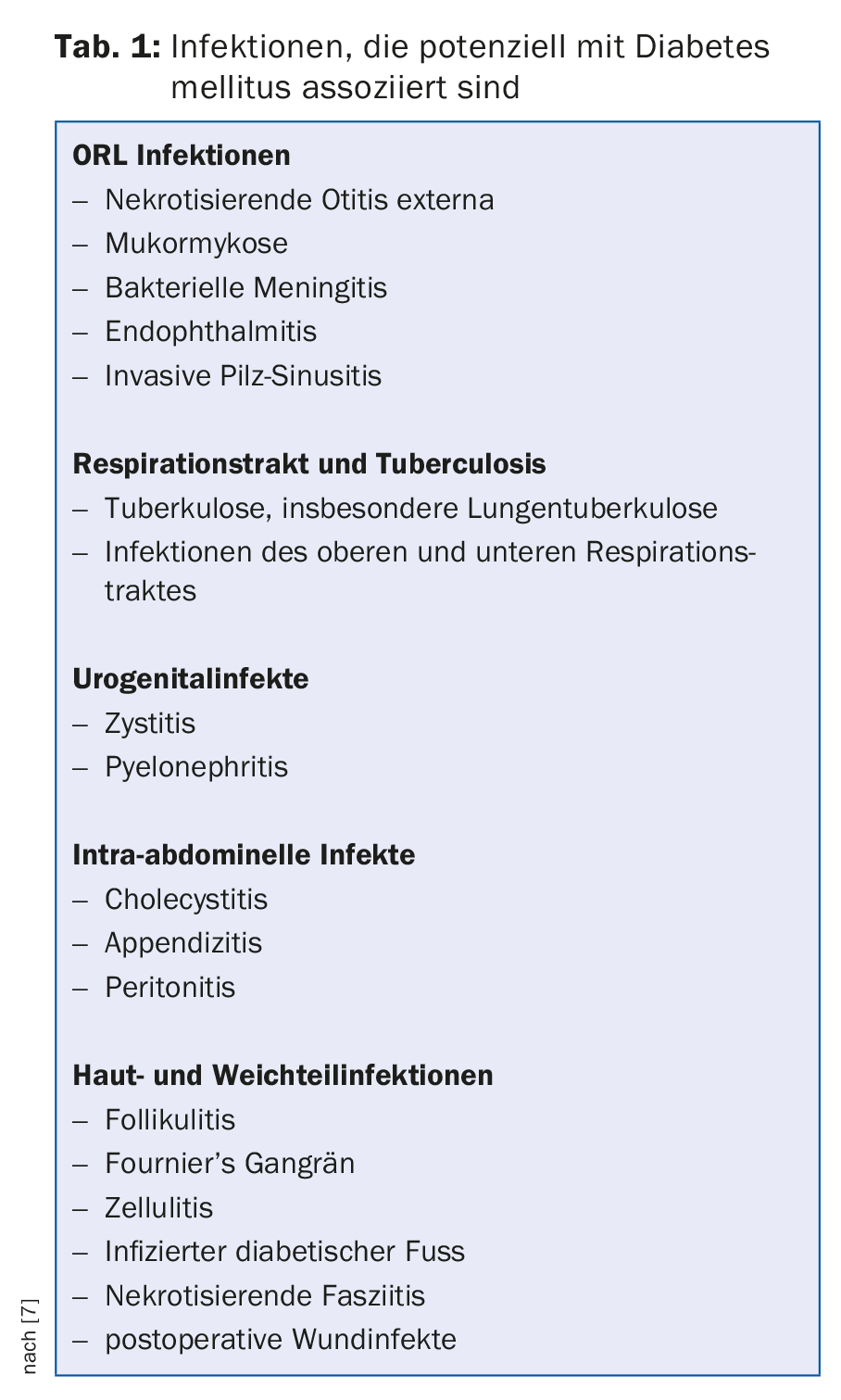

Various infections can be favored by diabetes (tab. 1) . The infections most frequently affected are those of the skin and the urogenital tract. The latter have occurred more frequently since the introduction of blood glucose-lowering therapy with SGLT2 inhibitors.

The following is a first part reporting on general infection risk considerations. In a second part, individual regions are examined in more detail.

Part 1: Overview of the “Diabetes Mellitus and Infection” Connection

Epidemiology and current study situation: In daily clinical practice, a frequent occurrence of infections in diabetic patients is seen.

Studies to date are unclear regarding the exact extent of a coincidence of diabetes and the occurrence of infection. Many studies are inconsistent, underpowered, or not controlled for confounders.

Observational studies show a strong association between high HbA1c and the risk of developing an infection. This applies to people with diabetes mellitus type 1 as well as type 2. Thus, a review article from 2011 [1] showed that there is a substantial increase in risk regarding infection-related mortality in diabetics.

Randomized-controlled trials show that microvascular and macrovascular benefits result from better glycemic control. A problem with many such trials is that older patients are often not included. However, in these, mortality from infections is similar to that from secondary complications of diabetes.

To date, no studies have conclusively demonstrated (even beyond age limits) that hyperglycemia is an independent risk factor for infection.

Many studies have also addressed postoperative mortality after coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) and general surgery. For example, a retrospective study showed a clear association between the presence of diabetes and the increased risk of postoperative wound infection (so-called “surgical site infection”) [2]. A linear relationship was found between the extent of blood glucose elevation and the risk of surgical site infection. However, the study was retrospective and did not show the same results in vascular interventions.

Early on, one of the most important epidemiological studies, the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT), showed increased infections in people with diabetes mellitus (all with type 1) [3]. For example, the incidence of vaginal infections among women in the intensified therapy group was reduced by almost half. Similarly pronounced results were obtained regarding the recurrence of diabetic foot infections and foot ulcers. At the end of the DCCT trial, the study became part of the Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications (EDIC) study as a follow-up. In one subanalysis-the Uro-EDIC study-the risk of pyelonephritis was statistically significantly reduced in intensified control (although the study was underpowered) compared “regular versus intensified” glycemic control.

More recently, a large UK cohort study on the association of glycemic control with infection incidence in people with type 2 diabetes was published in August 2016 [4]. The setting was family practices, infections such as upper respiratory tract infections, bronchitis, pneumonia, intestinal infections, herpes simplex, cutaneous as well as urogenital infections were studied. Patients were categorized as well controlled (HbA1c <7%), moderately controlled (7-8.5%), and poorly controlled (>8.5%). There were 34 278 patients included in 2014. The control group was 613,052 patients without diabetes. As expected, the incidence of all infections was higher in people with type 2 diabetes (except for herpes simplex).

Are there risk factors for infection in diabetes mellitus? The following host-specific factors are known:

- Suppression of immune response due to hyperglycemia. Further details in the excursus “Immunology”.

- Peripheral arterial occlusive disease as a secondary complication of long-standing poorly controlled diabetes leads to local tissue ischemia. This, in turn, may promote the growth of microaerophilic and anaerobic organisms while suppressing the oxygen-dependent bactericidal function of leukocytes. In addition, the tissue penetration of antibiotics may be reduced.

- Peripheral polyneuropathy can lead to skin ulceration from minor trauma, which in turn results in more frequent diabetic foot infections. Unfortunately, skin aging is not noticed or noticed too late by patients with reduced sensitivity.

- Urinary retention may occur in patients with diabetes-associated autonomic neuropathy. This stasis can lead to increased urinary tract infections.

- Diabetics have an increased colonization of the skin with Staphylococcus aureus and Candida species. The colonization is asymptomatic. Due to the impaired barrier function of the skin, invasive infections (with bacteremia u/o fungemia) may occur.

- Infections such as vulvovaginal candidiasis are more common in women with poorly controlled diabetes than in euglycemic patients.

- In addition, there are various organism-specific factors that predispose diabetics to infections, e.g., glucose-induced proteins can promote the adhesion of Candida albicans in an acidic environment (ketoacidosis).

Part 2: Illumination of individual regions

Certain infections (“signal infections”) are pathognomonic for diabetes, such as emphysematous pyelonephritis, necrotizing otitis externa, mucormycosis, and Fournier’s gangrene.

Upper respiratory tract infections: Necrotizing (“malignant”) otitis externa and rhinocerebral mucormycosis are two infections that occur almost exclusively in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Necrotizing otitis externa is seen mainly in patients over 35 years of age. Otorrhea and ear pain are the initial symptoms. Etiologically, a Pseudomonas aeruginosa is usually found. The infection can spread from the external ear canal to the surrounding soft tissue and into the cartilage and also into the bone. Surgical remediation and consequently early referral to an ORL specialist is essential.

Rhinocerebral mucormycosis most commonly presents in patients with very poorly controlled blood glucose. The molds of the order Mucorales primarily attack the paranasal sinuses and can also spread to the cerebrum via bone. Periorbital and perinasal pain/pressure sensation as well as swelling and redness are the early symptoms. CT to balance the infestation, surgical debridement followed by antifungal treatment appropriate for resistance are the mainstays of management.

Urinary tract infections: The increased rate of infections in the setting of the new oral antidiabetic agents (SGLT2) will not be discussed further here. I refer to the review article by Wiesli et al. in the Swiss Medical Forum [9].

Diabetics have an increased risk of suffering from bacteriuria and associated ascending urinary tract infections. Treatment selection is the same as for patients without diabetes, but the duration should be adjusted.

The treatment of pyelonephritis is also the same, but the threshold for hospitalization should be set lower, as complications are more frequent.

Emphysematous pyelonephritis is a very rare, necrotizing, gas-forming kidney infection caused by E. coli or Klebsiella pneumoniae. The presentation is identical to uncomplicated pyelonephritis and the diagnosis can be made if gas is detected on a conventional radiograph or CT or ultrasound. Therapeutically, antibiotics must be administered empirically on the one hand, and surgical debridement up to nephrectomy is usually indicated on the other.

Skin infections: These occur more frequently because diabetics with poorly controlled blood sugar over many years usually suffer sensory impairments in the feet. Polyneuropathy limits the sensory function and therefore the defensive function of the feet. Delayed healing occurs due to arterial occlusive disease. We will not discuss the diabetic foot here, but this deletive complication is very exemplary of the risk of infection in diabetics [10].

Bullosis diabeticorum is a spontaneous, non-inflammatory blister formation that occurs only in people with diabetes. Spontaneous healing is common, but cases of bacterial superinfection are not uncommon.

Soft tissue infections (including bacteremia depending on severity) can make any wound a complex challenge. The choice of antibiotic should be discussed with an infectious disease specialist. Necrotizing infections of the skin and subcutaneous tissue are usually polymicrobial in origin. Streptococci, S. aureus, Enterobacteriaceae and anaerobes can frequently be detected. For severe infections, management should be discussed on an interdisciplinary basis.

Osteomyelitis: Of course, infections of the skin and/or soft tissues can always lead to an infection of the underlying bone. Osteomyelitis has been found in up to 68% of cases in diabetic ulcers. The MRI and not the conventional X-ray should be consulted for diagnosis. In the case of osteomyelitis, empiric antibiotic therapy without collection of deep bacteriologic specimens is contraindicated. The resistance-appropriate antibiotic therapy duration should be parenterally administered for two weeks initially; usually followed by ten weeks of oral therapy.

Also feared as a complication of sternotomy is sternal infection in diabetic patients. A recent review (2016) [11] postulates risk factors for such infections: Female gender, diabetes mellitus, obesity, bilateral internal mammary artery grafts, reoperation, blood transfusion.

Conclusion

The association between diabetes mellitus and poor glycemic control with increased incidence of infections now appears to be confirmed in several recently published studies. An increased risk exists with HbA1c values above 8.5%, but even below this level there can be an increased incidence of infections and complicated courses of infections.

The increasing aging of our society makes it necessary to conduct more studies that include diabetics at an older age. The “thin line” between relaxed HbA1c targets (hypoglycemia) and clustered infections when glycemic control is too relaxed should be investigated in further prospective studies.

Acknowledgments: I would like to express my sincere thanks to Adrian Schibli, MD, FMH Infectiology, Zurich, for his valuable and critical review of the manuscript.

Literature:

- Seshasai SR, et al: Diabetes mellitus, fasting glucose, and risk of cause-specific death. N Engl J Med 2011; 364: 829-841.

- Ata A, et al: Postoperative hyperglycemia and surgical site infection in general surgery patients. Arch Surg 2010; 145(9): 858.

- McMahon MM, Bistrian BR: Host defenses and susceptibility to infection in patients with diabetes mellitus. Infect Dis Clin North Am 1995; 9(1): 1-9.

- Hine JL, et al: Association between glycaemic control and common infections in people with Type 2 diabetes: a cohort study. Diabet Med 2016 Aug 22. doi: 10.1111/dme.13205. [Epub ahead of print]

- Tessier D: Optimal glycaemic control in the elderly: where is the evidence and who should be targeted? Aging Health 2011; 7: 89-96.

- McGovern AP, et al: Infection risk in elderly people with reduced glycaemic control, Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2016; 4(4): 303-304.

- Pearson-Stuttard J, et al: Diabetes and infection: assessing the association with glycaemic control in population-based studies. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2016; 4(2): 148-158.

- Stegenga ME, et al: Hyperglycemia enhances coagulation and reduces neutrophil degranulation, whereas hyperinsulinemia inhibits fibrinolysis during human endotoxemia. Blood 2008; 112: 82-89.

- Wiesli P, et al: Diabetes and urogenital infections under SGLT2 inhibitors. Switzerland Med Forum 2016; 16(16): 363-368.

- Bowling, FL et al: Preventing and treating foot complications associated with diabetes mellitus. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2015; 11: 606-616.

- Balachandran S, et al: Risk Factors for Sternal Complications After Cardiac Surgery: A Systematic Review. Ann Thorac Surg 2016 Aug 20. [Epub ahead of print]

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2016; 11(12): 8-11