Young people with first-time knee swelling often seek advice from their primary care physician. Among the possible causes, one should think of patellar luxation. This is preceded by a sports accident that is usually not very spectacular. Diagnosis is relatively clearly systematized; treatment remains controversial. Conservative or immediate surgery?

It should be clear that “knee distortion” is not a sufficient diagnosis. Thus, in the case of appropriate acute trauma from sports, it is always a matter of meticulously searching for the exact lesion (or lesions). With knee joint effusion (hemarthrosis) present, the most common injuries are those to the anterior cruciate ligament, peripheral meniscal tears, fractures, especially of the tibial plateau, and patellar luxation. Somewhat less common are injuries to the lateral collateral ligaments, osteochondral lesions, and patellar fractures. Even rarer are extensor injuries and complete knee dislocations, but one does well not to forget them.

In the absence of joint effusion, injuries to the medial collateral ligaments and central meniscal tears are the first to come to mind; posterior cruciate ligament injuries and cartilage injuries are somewhat less common. It is also important to consider growth plate injuries in young patients with incomplete growth.

Combinations of different injuries are possible and even common (up to 75% depending on the data). With this list of differential diagnoses in mind, one can now approach the history and examination.

Patellar luxation clinic

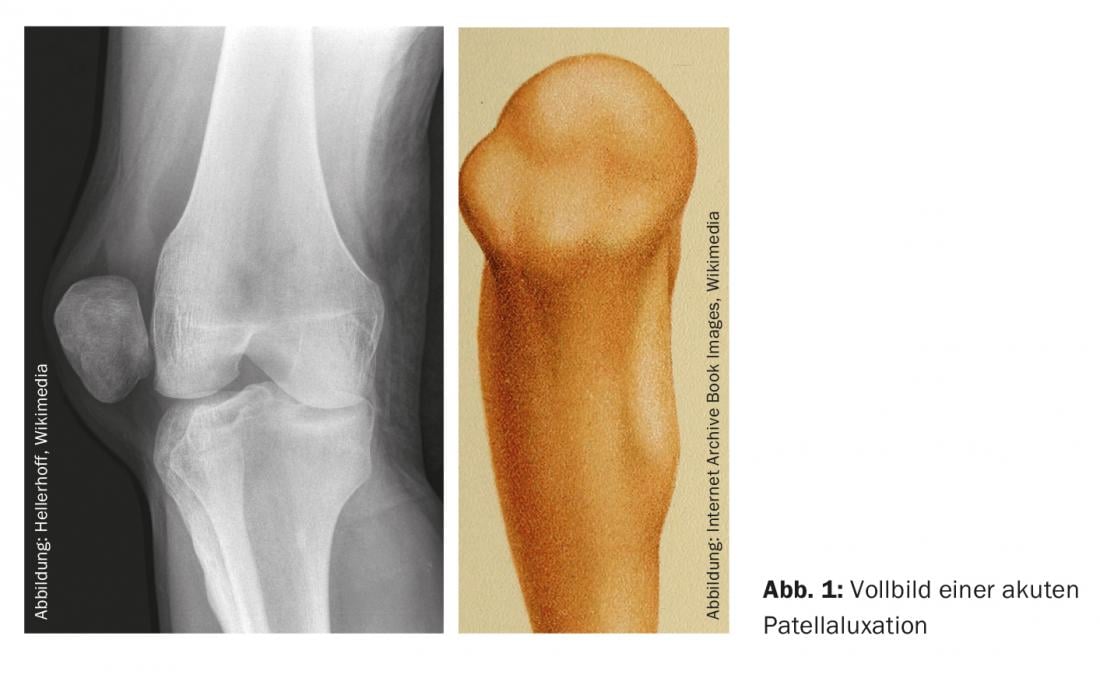

If one were always to encounter the classic clinical (and additionally radiological) full picture of acute patellar luxation, the diagnosis of this clinical picture would probably be one of the simplest in medicine at all ( Fig. 1). The classic deformity of the affected knee joint with the clearly visible lateral elevation actually leaves no room for doubt. And the axial patella radiograph is self-explanatory.

However, this clinical situation is rather rarely encountered, so it is important not to miss the not so rare pathology, as it requires specific treatment. We want to discuss the way to get there.

In the acute event on the sports field and if the patellar dislocation is not spontaneously reduced, the primary care provider will find a patient with severe pain as well as a knee that is usually fixed at approximately 45° of flexion. On closer examination, this joint will show the typical lateral deformity, which must be reduced as quickly as possible. As with the shoulder, the closer the event, the easier this is accomplished; sometimes all that is needed is external rotation of the leg and careful extension. A gentle elevation of the medial patellar rim can be additionally beneficial in this regard. Initial care should be supplemented with bandaging, ideally splinting, and the PECH protocol. In certain situations, reduction must be performed under either brief sedation or local anesthesia.

This is followed by the more detailed clarification, as it should also take place in practice. We assume that the dislocation has been reduced.

Medical history

In the anamnesis, the usually young person, according to statistics often female, will rather rarely speak of a relevant trauma. In the case of skiers, it can be a blow with the inside of the knee against a pole; in contact sports such as soccer and handball, for example, it can be a banal collision with the opponent’s leg, again against the inside of the knee; in the case of basketball players, it can be a change of direction when dribbling with a more or less fixed foot (leg in external rotation and knee in valgus position, almost in extension). Upon close analysis, a powerful quadriceps strain was involved.

The popping out of the kneecap as well as the return to the normal position are clearly noticed by the patient – sometimes as an internal pop (“double clicking pop”). The whole affair was painful and the knee swelling is rapid.

Investigation

During the examination – usually taking place in a sitting or even lying position on the examination couch due to disability – the clear effusion will be noticeable. The extension should actually be normal except for the cast-related disturbance, but the flexion is usually limited and even painful in the final degree. The stability test battery for all bands will be normal. For this, the careful patellar palpation medially will be quite painful. If the patellar stability test is performed carefully in the early phase, a clear reaction will be observed during the lateralization test (“positive lateral patellar apprehension test”).

It goes without saying that, despite a fairly typical history, the injured joint is fully examined to rule out injuries of a similar character to rupture of the quadriceps or patellar tendon (usually without joint effusion).

Treatment

The joint effusion, which is almost always present, invites (comfort-enhancing) puncture. This is recommended, but may only take place after radiographic clarification has been performed, since a bone lesion is an almost absolute contraindication to puncture. Thus, an a.p., lateral knee as well as an axial patellar radiograph should be obtained to rule out a bony avulsion at the medial patellar rim or an osseous condylar injury. In the absence of such lesions, puncture may be performed under absolute sterility. In case of doubt, it should rather be dispensed with.

Fractures are considered an absolute indication for surgery according to certain authors. If such are present, we recommend a specialist referral (orthopedist).

A compression bandage, the fitting of a jeans or mekron splint in extension, the recommendation to apply ice packs regularly throughout the day for 10-15 minutes, crutches for partial to full relief according to pain sensation, pain medication or NSAID if necessary, a physiotherapy prescription with the recommendation of progressive mobilization of the joint and activation of the patella-stabilizing musculature, possibly with electromyostimulation, as well as an application for MRI clarification conclude the initial consultation.

Imaging should be more or less rapid. Follow-up visits to assess progress, discuss images, and determine further action will take place immediately thereafter.

Patella stabilization

During dislocation, the patella shifts 6-7 cm, almost exclusively laterally, so it is not difficult to imagine what happens to the medial soft tissue structures. These must be overstretched to the same extent – and injured accordingly.

In recent years, much research and writing has been done on medial patella stabilizing structures. The MPFL (“medial patellofemoral ligament”) is a thin reticular tissue that extends femorally between the adductor tuberosity and the medial epicondyle to the patellar medial aspect of the inferior layer of the vastus medialis obliquus (VMO) muscle. Already only passively, this structure accounts for 50-60% of the stabilizing forces against lateral displacement of the patella. The connection to the VMO additionally confers dynamic stabilization.

MRI allows assessment of the condition of the MPFL, which according to the literature is injured in 50-94% of acute patellar dislocations. MRI will also be able to detect cartilage injuries (osteochondral fractures) – another surgical indication according to the majority of authors. Rupture of the MPFL is still a relative indication for surgical suture or reconstruction for this (more the trend today).

Second consultation hour

The second meeting with the patient should have very clear goals:

- Discussion of the results of the MRI

- Clinical reevaluation, especially search for favoring factors

- Determination of the further therapy strategy

As seen by experienced radiologists, MRI should clearly show the presence of osteochondral lesions (“flake-fracture”) not detected on radiography, free joint bodies, cartilage damage, and the condition of the medial fixation system (retinaculum mediale, MPFL). Information should also be provided on the architecture of the trochlea (trochlear dysplasia) and the entire patellofemoral joint (patella alta), which, in addition to the radiograph, provides important information regarding risk factors.

The renewed clinical examination should now also be able to take place in the standing position, comparing sides. In addition to checking the primary findings noted (effusion, flexion-extension, stability, etc.), predisposing factors such as the position of the leg axis (genua valga), torsional abnormalities (increased femoral anteversion, external tibial torsion), tibial tuberosity malposition, Q-angle elevation greater than 15°, muscle weaknesses (VMO), patellar instability, and general ligamentous laxity are checked.

If referral to specialists is recommended in the presence of structural damage (exclusive tears of the MPFL) and clearly predisposing factors, the treatment established in the first encounter may be continued in the event of re-dislocation.

It may be that a second joint puncture is useful. At best, the knee brace can be replaced by a special “patella-stabilizing” bandage and the patient can be carefully and progressively moved to full weight-bearing without crutches.

Disagreement regarding therapy

In acute traumatic patellar dislocation – not to be confused with habitual dislocation – there is consensus regarding diagnosis. This does not apply to therapy. The reason is the risk of recurrence, which is estimated to be up to 50% without surgery according to various studies. Nevertheless, it seems to be generally accepted to adopt conservative therapy at the first event without bone or cartilage damage (as described above). The duration of this controlled treatment should be approximately six weeks. In young active individuals with reasonably normal skeletal architecture of the patellofemoral joint, it produces satisfactory results. Conversely, with significant shape variations, the risk of recurrence increases significantly.

MPFL

As mentioned above, the MPFL is currently a major research focus. The exact location of the injury to this stabilizer – patellar, mid, femoral – also seems to play a role. The area with the best chance of scarring (equating to better stabilization) is where the MFPL and VMO overlap, and the area with the worst chance is at the femoral approach.

When it comes to surgery, today’s trend is reconstruction rather than suturing the injured ligament. However, this procedure is not yet part of the orthopedic routine and is therefore performed only by specialists in the problem.

Conclusion

General practitioners or pediatricians are repeatedly confronted in their consultation hours with (mostly) young persons who seek advice because of a first-time knee swelling (after a usually not very spectacular sports accident). Among the possible causes of such a disorder, patellar luxation should also be considered. Along with anterior cruciate ligament rupture and acute meniscal tear, it is the most common cause of joint effusion. The difficulty in making the diagnosis clinically lies in the fact that after acute dislocation, reduction very often occurs spontaneously.

The situation is different if the colleague acts as a sports event supervisor (an absolutely rewarding activity) or occasionally works in an emergency ward (also quite an interesting activity). In this setting, the likelihood of a full clinical and even radiographic picture of the problem would increase. According to the literature, the incidence is 6 per 100,000 in the entire population, 29 per 100,000 in 10-17 year olds, and as high as 104 per 100,000 active young women. So the suffering is not so rare.

If the diagnosis of acute patellar luxation is relatively clearly systematized, its treatment currently remains controversial. Conservative or immediate surgery? Opinions differ on this. Nevertheless, there are good guidelines for both paths, and after a conservative strategy has not led to success, it is still possible to resort to the surgical solution in case of any recurrence problems.

Finally, it should be pointed out that the management of habitual patellar luxation should be guided by other criteria.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2017; 12(6): 4-6