Modern asthma therapy is phenotype-based. Long-term treatment goals are good symptom control and minimization of the risk of exacerbations. However, symptom control does not equate to asthma severity.

Asthma is a heterogeneous, multifactorial often chronic inflammatory or eosinophilic disease of the airways, usually with bronchial hyperresponsiveness and/or variable airway obstruction. Modern asthma therapy is phenotype-specific, which requires a correspondingly differentiated diagnosis. Long-term goals of asthma management are primarily good symptom control and minimizing the risk of exacerbations and drug side effects. For good symptom control, the following criteria should be met: Use of a short-acting β2-agonist (SABA) is not required more than twice weekly, and normal physical activity (including daily exercise) does not cause cough and dyspnea. The Asthma Control Test (ACT®) [1] is a structured diagnostic tool that can be used to assess symptoms by asking specific questions.

Symptom control does not equal severity

Good control of severe asthma is possible with extended therapy, but severe symptoms may be present in a patient with mild asthma – for example, in the case of inadequate therapy, exposure to allergens, or in the setting of a viral airway infection. Exacerbations can occur even with good symptom control and are characterized by more frequent dyspnea, an increasing need for short-acting β2-agonists, and a significant decrease in peak flow, respectively. For objective findings, the primary care physician can collect spirometric control of FEV1 and determination of the blood eosinophil count in the differential blood count. In the context of a pneumological clarification, further conclusions can be drawn on the basis of the measurement of FeNO. It is important to control FEV1 not only in symptomatic phases but also in symptom-free phases. This allows for the individual best FEV1 on which long-term therapy is based, among other things.

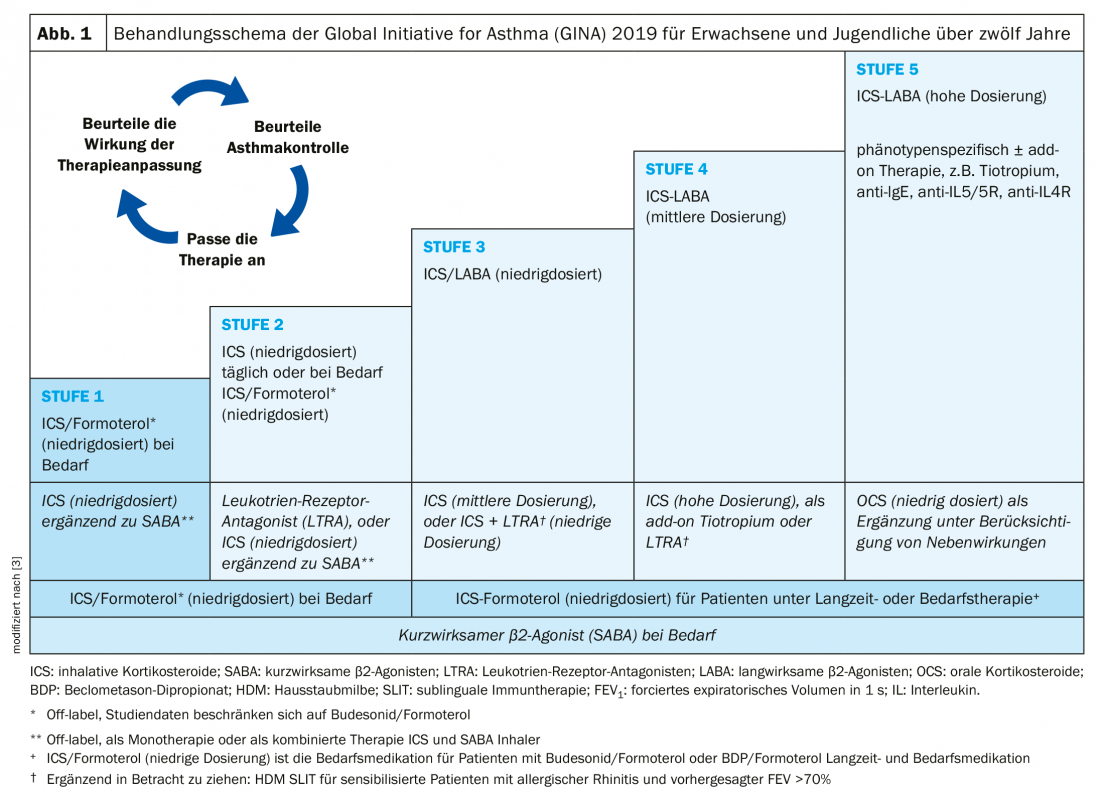

Asthma medications are divided into long-term therapeutics (“controllers”) and as-needed medications (“relievers”). Therapy is based on a stepwise scheme according to international GINA asthma guidelines [2] (Fig. 1):

- Stage 1: Therapy is given only with a short-acting β2-agonist (SABA) when needed, which should be no more than twice a week.

- Stage 2: If an emergency medication is needed more frequently, low-dose inhaled steroids (ICS) must be prescribed fixed.

- Stage 3: Inhaled steroid dose must be increased and/or long-acting β2-agonists (LABA) added fixed for adequate asthma control.

- Stage 4: Regular use of high-dose inhaled steroids (ICS) in combination with long-acting β2-agonists (LABA) is required.

- Stage 5: Therapy must be further supplemented, for example with biologics or daily oral corticosteroids.

Asthma of mild severity is when the disease is controllable with levels 1 or 2, respectively. If level 3 is necessary, moderate-severe asthma is present. Therapy intensity of level 4 or 5 is required for severe asthma. Severe asthma includes cases requiring level 4 or 5 treatment (high-dose inhaled corticosteroids in combination with a second long-acting β2-agonist), including patients who achieve inadequate symptom control despite good adherence and adequate inhalation technique [2].

According to the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA), the classification into uncontrolled, difficult-to-treat, and severe asthma is based on the following distinguishing criteria [2]:

- Uncontrolled asthma is present when one or both of the following criteria are met: 1) Poor symptom control (frequent symptoms or need medications, asthma-related limitations of daily activities, nighttime awakenings; 2) frequent exacerbations (≥2 per year) and appropriate use of oral corticosteroids (OCS) or serious exacerbations (≥1 per year) followed by hospitalization.

- Criteria for difficult-to-treat asthma are: Lack of symptom control and occurrence of exacerbations despite treatment according to GINA level 4 or 5, e.g. with moderate or high-dose inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) with a second long-term therapeutic agent; maintenance therapy with OCS). In many cases, asthma appears difficult to treat because of various modifiable factors such as incorrect inhaler technique, inadequate adherence, smoking, or comorbidities, or because the diagnosis is inaccurate.

- The severe asthma category subsumes various forms of asthma that are difficult to treat. It means that inadequate symptom control is achieved despite adherence with maximally optimized therapy as well as treatment of other disease-relevant factors, or a worsening of the condition with a reduction in high-dose treatment.

Clarification algorithm for difficult to treat asthma

At this time, “severe asthma” is a retrospective classification. Sometimes it is referred to as severe refractory asthma, as treatment resistance to high-dose inhaled therapies is a criterion. Since the market approval of biologics, however, there is no longer any talk of refractoriness. In difficult-to-treat asthma, the following clarification algorithm is suggested [2].

- Verify diagnosis: Is it really asthma? If there is any uncertainty after examination, including spirometric determination of FEV1, referral to a pulmonologist or physician should be made. other specialists are made. Possible differential diagnoses include infectious or cardiac causes or bronchioectasis.

- Are there other modifiable factors that affect symptoms and exacerbations? (e.g., incorrect inhalation technique; inadequate adherence; comorbidities including anxiety and depression, obesity, chronic rhinosinusitis, laryngeal obstruction, GERD, COPD, obstructive sleep apnea, bronchioectasis, cardiac disease, osteoporotic kyphosis); triggers (e.g., smoking, environmental factors, etc); overuse of SABA; anxiety, depression, social and financial problems; medication side effects.

- Can the therapy be optimized by one/more of the following measures? Patient education; long-term inhaled therapy; treatment of comorbidities and risk factors; complementary non-pharmacological therapy e.g. smoking cessation, diet, exercise); complementary non-biologic agents to moderate to high dose ICS e.g.: LABA, tiotropium, leukotriene; high dose ICS if only low dose previously.

- Evaluate response after 3-6 months: How have the following parameters developed? Symptom control, exacerbations, medication side effects, inhalation technique and adherence, pulmonary function, patient satisfaction and concerns.

If the asthma is still uncontrolled despite optimization of therapy, it can be assumed to be severe asthma. The patient should be referred to a specialist or to a clinic specializing in asthma treatment if this has not been done before. If asthma is well controlled after implementation of the measures described, downgrading of therapy may be considered. This means initially reducing any OCS, and later omitting other therapies and reducing ICS dosage (do not discontinue ICS completely). There is detailed guidance on how to do this in the GINA 2019 guidelines [2].

Phenotype-based therapy: consider alternatives to oral steroids

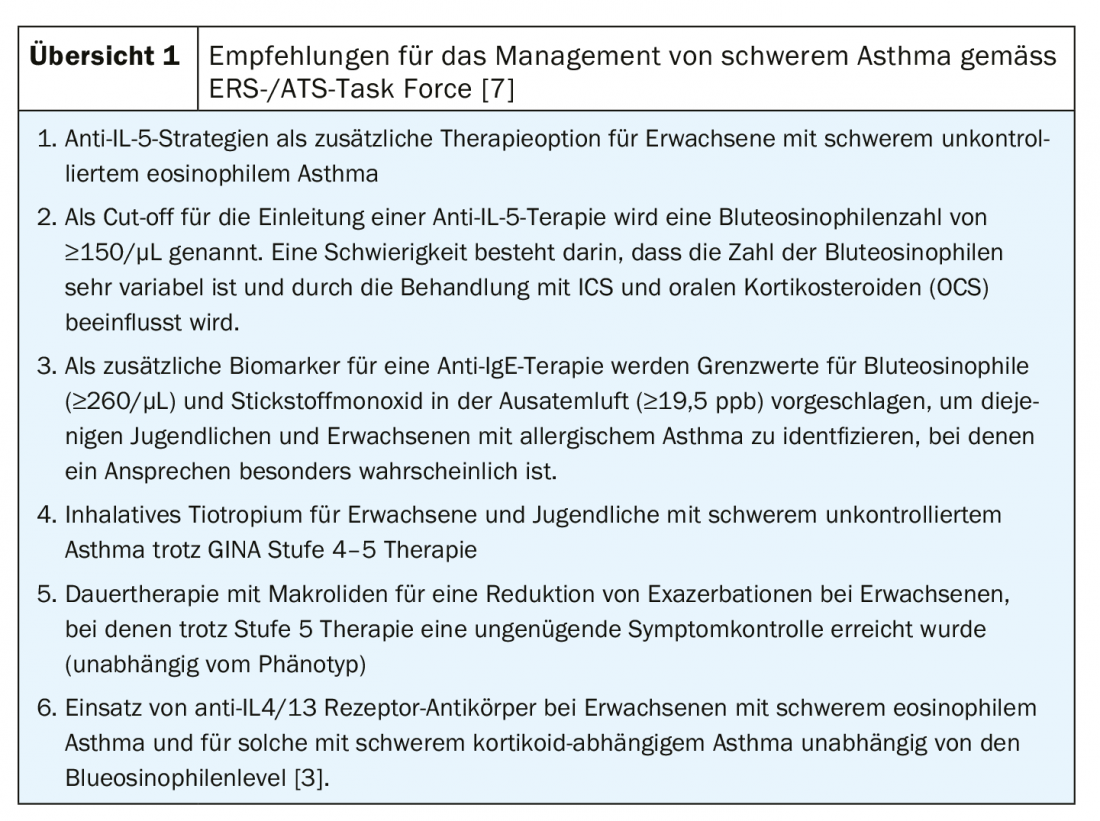

Overuse of oral steroids remains common in patients with severe asthma as shown by data from the Netherlands presented at the 2019 ERS Congress [4]. The reasons for this are assumed to be, on the one hand, suboptimal inhaler use and, on the other hand, restrained prescription of biologics. Prior to any prescription for oral corticosteroids, physicians should verify that the patient is adherent to and correctly using his or her inhaled therapy. In addition, the possibility of a biologic should be considered [4]. Initiation of therapy with biologics from level 5 requires the criteria of severe asthma. The therapeutic goal, in addition to improving asthma control, is to reduce OCS and prevent exacerbations [5]. Five biologics are now available for the treatment of severe asthma when symptom control is not achieved despite continuous therapy with high-dose ICS and a long-acting betamimetic. The monoclonal antibody dupilumab is an IL-4/13 receptor antagonist. Mepolizumab, reslizumab, benralizumab are antibodies against IL-5 and the IL-5 receptor, respectively. The large cohort study IDEAL showed a strong correlation between IL-5 and eosinophils in severe asthma [6]. A task force of ERS and ATS evaluated the evidence on these and other new therapeutic options (azithromycin, tiotropium) in meta-analyses and derived six recommendations for the management of severe asthma [7] (review 1).

Literature:

- Asthma Control Test, www.asthmacontroltest.com

- Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA): 2019 Difficult-to-treat and severe asthma, https://ginasthma.org/severeasthma

- Reddel HK, et al: GINA 2019: a fundamental change in asthma management, European Respiratory Journal 2019; 53: 1901046; DOI: 10.1183/13993003.01046-2019.

- Eger K, et al: Overuse of oral corticosteroids in asthma – modifiable factors and potential role of biologics, Abstract OA5334, presented at ERS 2019.

- Powitz F: Bronchial asthma. Update 2019, MMW Advances in Medicine, Special Issue 1/2019, www.springermedizin.de/asthma-bronchiale/kindliches-asthma/asthma-bronchiale/16574534

- Müllerova H, et al: Associations of blood cytokines and eosinophils in severe asthma. PA633, ERS Congress, September 10, 2017.

- Holguin F, et al: ERS and ATS guideline Six new recommendations for severe asthma, Eur Respir J. 2019: Management of Severe Asthma: a European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society Guideline. Eur Respir J 2019 Sep 26. pii: 1900588. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00588-2019. [Epub ahead of print]

GP PRACTICE 2020; 15(1): 23-25.