Do hot drinks like tea or coffee affect breast cancer risk? And what about drinking such beverages when a breast cancer patient is undergoing chemotherapy? At the Breast Cancer Conference in Amsterdam, speakers and participants addressed these topics, among others. We report four studies in nutrition, mastectomy, and cardiac dysfunction after cancer therapy.

A study from the Netherlands addressed the question of how breast reconstruction should be timed after mastectomy [1]. The participating patients underwent mastectomy with subsequent breast reconstruction using implants. In one group, mastectomy and implantation (supported by an acellular dermal matrix) were performed one-stage, in the other group two-stage. A total of nearly 120 patients from eight hospitals in the Netherlands were included in the study, and the primary endpoint was quality of life. The interventions were performed between April 2013 and May 2015. Mastectomy and breast reconstruction were performed one-stage in 59 patients (91 breasts) and two-stage in 59 patients (87 breasts).

This showed that in the group with a single-stage procedure, the course was significantly worse: there were more frequent medical complications (38.5% vs 10.3%; OR=6.28; p=0.001), reoperations occurred more frequently (32.6% vs 9.6%; OR=3.96, p=0.009), and the implants had to be removed more frequently (27.0% vs 2.4%; OR=15, p=0.001). Based on these results, the authors recommend being very cautious when considering a single-stage procedure.

Cardiac dysfunction in women after breast cancer therapy.

Chemotherapy and radiotherapy for breast cancer increase survival but can have a side effect of impairing cardiac function. The prevalence of cardiac dysfunction in breast cancer survivors is unknown.

A Dutch study included 350 women whose breast cancer treatment with chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy was at least five years old [2]. These former patients were compared with a control group of 350 women who did not have cancer. Systolic or diastolic dysfunction, defined as an ejection fraction below 54%, was sought. The breast cancer patients were divided into two groups: Those treated with chemotherapy (as monotherapy or in combination with radiotherapy) (n=175) and those treated with radiotherapy only (n=173). Cardiovascular risk factors were similarly prevalent in all groups (former patients as well as control group). The average duration of follow-up was nine years (5-33 years).

Systolic dysfunction was present in 14.7% of patients in the chemotherapy group, 16.6% in the radiotherapy group, and 6.6% in the control group. The corresponding distribution of diastolic dysfunction was 46.8% (chemotherapy), 40.6% (radiotherapy), and 39% (control group). For the women after chemotherapy or radiotherapy, the risk of developing systolic dysfunction was increased by a factor of 2. The risk of diastolic dysfunction was the same as in the control group.

Does mate tea protect against breast cancer?

The consumption of mate tea (infusion from the plant Ilex paraguariensis) is widespread in South America (Fig. 1) . Various studies indicate that mate tea may increase the risk of some cancers, especially esophageal cancer. Whether mate tea may also play a role in the pathogenesis of breast cancer has not yet been investigated. Therefore, the present study was carried out in Montevideo, the capital of Uruguay [3].

Participants were divided into two groups: 111 had breast cancer and 222 had a normal mammogram. The women completed a questionnaire on their dietary habits, and were also asked about other sociodemographic and medical aspects (including lifestyle). The study focused on the consumption of hot beverages (coffee, tea, etc.).

In the third of women with the highest consumption of mate tea or normal tea (infusion from Camellia sinensis) , the risk of developing breast cancer was significantly reduced; in women who drank a lot of mate tea and a lot of normal tea, the risk of breast cancer was even lower (additive effect). High coffee consumption was not associated with an increased risk of breast cancer.

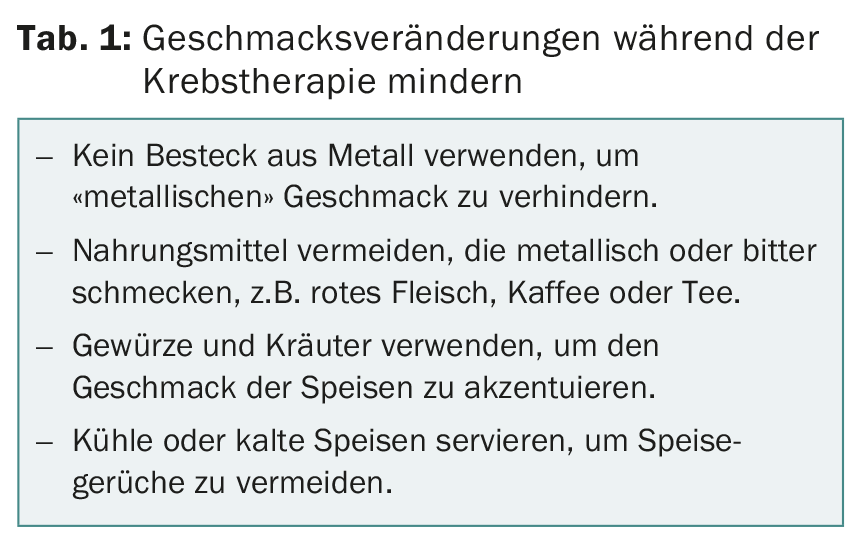

Altered taste perception during chemotherapy

Many cancer patients experience changes in their perception of smells and tastes during chemotherapy. For the affected patients, these changes are not only distressing, but they also frequently impair food intake. In the present small study, a total of 60 women were examined and interviewed: 30 underwent chemotherapy for newly diagnosed breast cancer, and 30 women were healthy. The average age of the participants was 52 years.

Taste and smell functions of the study participants were tested before the start, at the middle, and one to three weeks after the end of chemotherapy. At the same time, they were asked about their food preferences. In the process, the women were able to select appropriate sweet and salty foods, which were presented to them as pictures on the computer. It was found that the patients could taste less during chemotherapy than the women in the comparison group; there were no changes in the function of the sense of smell. This results in practical recommendations for the everyday life of cancer patients (Tab. 1).

Source: European Breast Cancer Conference, March 9-11, 2016, Amsterdam.

Literature:

- Dikmans R, et al: Two-stage implant-based breast reconstruction is safer than immediate one-stage implant-based breast reconstruction augmented with an acellular dermal matrix: a multicentre randomized controlled trial. European J of Cancer 2016; 57, suppl. 2 (abs 1LBA).

- Boerman LM, et al: Long-term outcome of cardiac dysfunction in a population-based cohort of breast cancer survivors. European J of Cancer 2016; 57, suppl. 2 (abs 2LBA).

- Ronco A, et al: Hot infusions and risk of breast cancer: A case-control study in Uruguay. European J of Cancer 2016; 57, suppl. 2 (poster 114).

- De Vries Y, et al: Taste, smell and food preferences during chemotherapy in breast cancer patients. European J of Cancer 2016; 57, suppl. 2 (Poster 182).

- Hong J, et al: Taste and Odor Abnormalities in Cancer Patients. J Support Oncol 2009; 7:58-65.

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2016; 4(3); 31-32.