Proton pump inhibitors (PPI) are still the first choice for acute treatment, but long-term use should be avoided. H2 antihistamines also suppress gastric acid secretion. Antacids and alginates can also reduce reflux symptoms. At the same time, lifestyle measures can help to alleviate symptoms. Fundoplication may be an option if there is no response to drug therapy. In patients with alarm symptoms, it is recommended to endoscope promptly and in individual cases pH-metry is useful.

In gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), the reflux of stomach contents leads to disturbing symptoms and/or complications [1]. Established risk factors for the development of GERD include genetic predisposition, an elevated body mass index (BMI), nicotine abuse and hiatal hernia [2,3]. There is no gold standard for diagnosing reflux disease, explained PD Dr. med. Christoph Schmidt, Gastroenterology Practice, Bonn. “If there is a reasonable suspicion of reflux, treatment can initially be given on a trial basis,” said the speaker [4]. However, in the event of alarming symptoms, endoscopy should be performed quickly, and in individual cases a computer tomography (CT) scan may also be useful, Dr. Schmidt explained [4].

Endoscopic classification

The following criteria suggest an endoscopy:

- Dysphagia

- Odynophagia

- Indications of gastrointestinal bleeding (including iron deficiency anemia)

- Anorexia

- Unintentional weight loss

- Recurrent vomiting

- Family history of gastrointestinal tumors

“If the endoscopy is unremarkable, you have to think about whether you should perform pH-metry or nanometry to quantify the reflux events,” reported Dr. Schmidt [4]. The current guideline emphasizes that the Los Angeles (LA) classification, in contrast to other endoscopic classifications such as Savary-Miller or MUSE, has been substantially validated and correlates with the results of functional diagnostic examinations [1]. Therefore, the Lyon consensus also refers to this classification [5]. According to the Lyon consensus, an erosive reflux lesion Los Angeles C or D, a Barrett’s esophagus (histologically >1 cm), a peptic stenosis or a pathological pH-metry with an acid exposure time >6% are considered to be conclusive evidence for the diagnosis of GERD [1]. With LA grade B and typical reflux symptoms, the diagnosis of GERD can be made with a high degree of probability [6]. Low-grade reflux esophagitis LA grade A may be an incidental finding, but the presence of typical reflux symptoms suggests GERD [1].

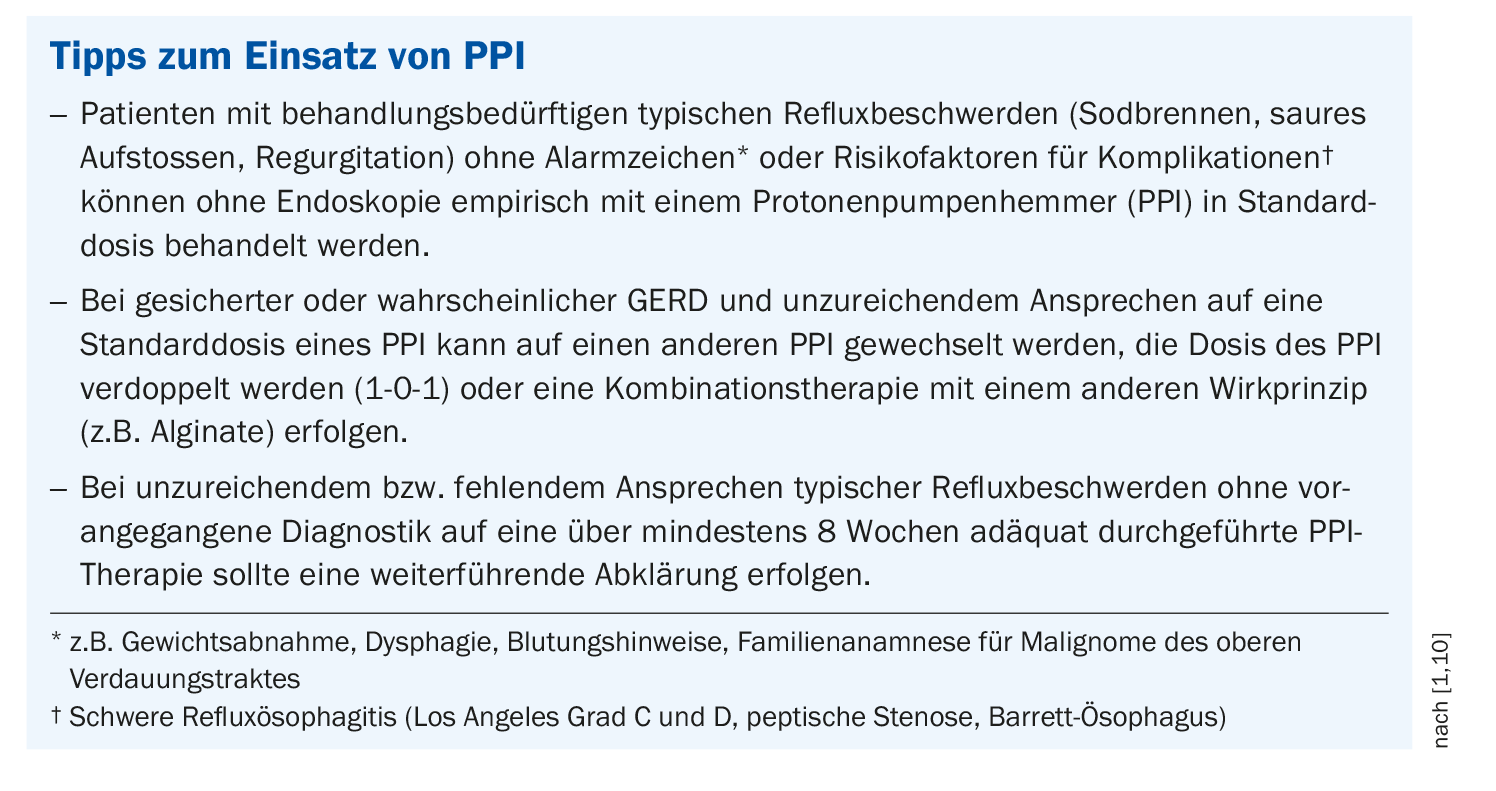

PPI as proven acute therapy

For typical symptoms without “red flags” and without risk factors (e.g. negative family history of oesophageal cancer), proton pump inhibitors (PPI) for four weeks are the treatment of choice (box) . Alternatively, an H2 blocker such as famotidine or ranitidine can be used. For mild symptoms, healing clay, antacids or alginate may also provide relief. “As a rule, we use PPIs,” Dr. Schmidt qualified [4]. If the patient is symptom-free for 4 weeks (Los Angeles A and B) or 8 weeks (Los Angeles C and D) after full-dose PPI therapy, this is a good predictor of healing of the esophageal lesions [1]. The PPI should be taken on an empty stomach (30-60 minutes before a meal). “They should never be discontinued abruptly, as this leads to excessive acid production, an acid rebound,” emphasized Dr. Schmidt [4]. The current s2k guideline takes the following position on reports of alleged or actual adverse effects of PPIs, which have been increasingly cited in recent years: the absolute risk of side effects for PPIs is low or, in the case of GERD, the benefit outweighs the risk [1]. The speaker confirmed that PPIs are generally well tolerated and that side effects are rare [4]. Occasionally, iron deficiency or magnesium deficiency can occur and some patients react with diarrhea or headaches. In addition, the risk of infection is slightly increased when gastric acid production is inhibited and, as PPIs are metabolized via CYP450, interactions with other medications may occur. Continuous PPI therapy is only necessary in rare cases, in which case intermittent use as required is recommended [4].

What options are there if there is no response to PPI?

If patients do not respond to a double-dose acid blocker for 4 weeks, one could change the PPI and/or consider a combination with alginate, Dr. Schmidt recommended [4]. If symptoms persist despite adequate, high-dose PPI therapy lasting up to 8 weeks, it is first necessary to clarify whether they are really typical reflux symptoms. Patients with GERD may have concomitant diseases such as coronary heart disease (CHD), an irritable stomach or irritable bowel syndrome. It is also not uncommon for a somatization disorder to be present, which can be suspected or identified on the basis of a variety of symptoms that often cannot be attributed to one cause [7]. For this reason, all symptoms should be recorded and explicit questions asked about which symptom(s) do not respond to PPI. As an alternative to drug therapy, surgery in the form of a fundoplication can be performed, but this is the exception rather than the rule, the speaker reported [4].

It should be borne in mind that chronic reflux esophagitis and Barrett’s syndrome increase the risk of esophageal cancer. Barrett’s syndrome usually occurs at an advanced age. According to the s2k guideline, a “once-in-a-lifetime” endoscopy is recommended for chronic reflux patients in order to detect or rule out Barrett’s esophagus [1].

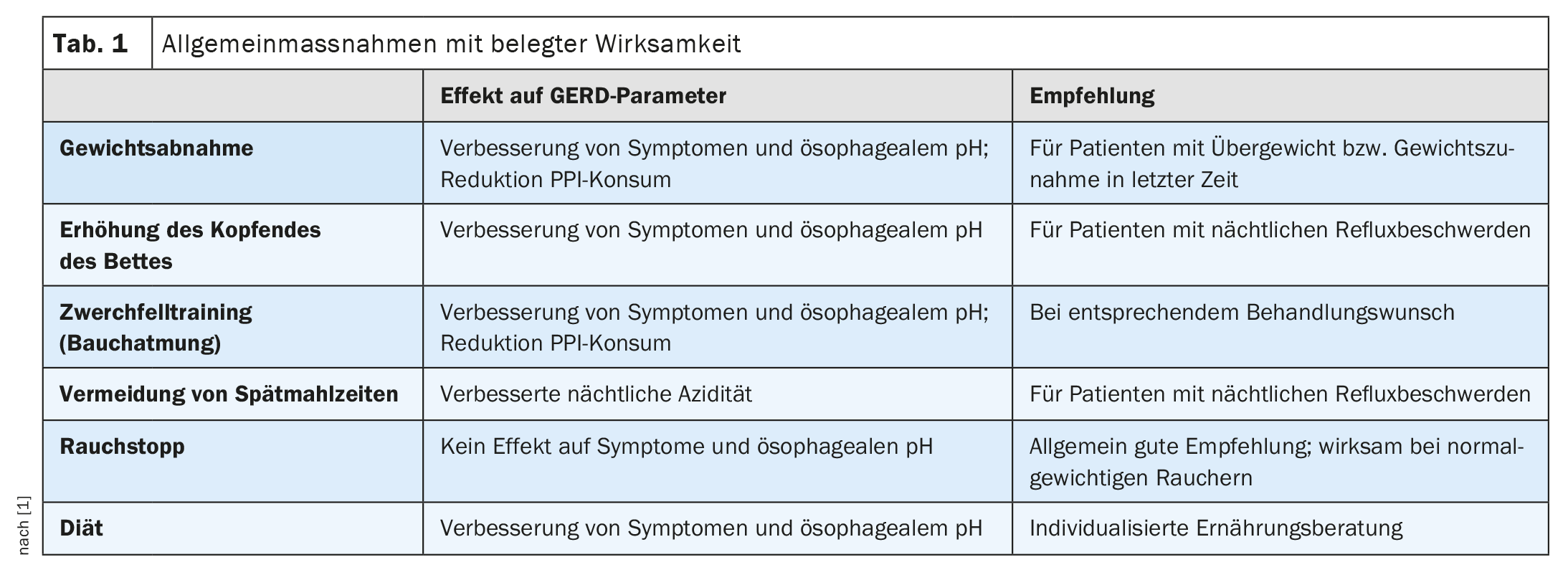

What lifestyle measures are there?

As general measures (Table 1) , Dr. Schmidt mentions weight normalization, sleeping with the upper body slightly elevated (left-sided position is more favourable), avoiding late meals, stopping smoking, diaphragm training and, if necessary, avoiding certain foods [4]. However, the latter is not supported by evidence, the speaker said, adding: “Cutting out coffee, mineral water, citrus fruits and spicy foods can be helpful in individual cases, but you should not prescribe too many dietary measures” [4]. However, there is scientific evidence on the other factors: in the HUNT study, for example, weight loss was associated with an improvement in reflux symptoms and there are several randomized controlled trials on the recommendation to raise the head of the bed in patients with nocturnal reflux symptoms [1,8]. There is also supporting evidence from two case-control studies and one randomized controlled trial for not eating late meals [9,10]. The left-sided position is a plausible explanation for reduced nocturnal reflux for anatomical reasons. In a population-based cohort study, smoking cessation led to an improvement in symptoms in patients of normal weight [8]. Tight clothing or tightly buckled belts should be avoided, as they lead to an increase in reflux.

Congress: FomF General Medicine Refresher

Literature:

- S2k guideline Gastroesophageal reflux disease and eosinophilic esophagitis of the German Society for Gastroenterology, Digestive and Metabolic Diseases (DGVS), March 2023, AWMF register number: 021-013. Z Gastroenterol 2023; 61(7): 862-933.

- Eusebi LH, et al: Global prevalence of, and risk factors for, gastro-oesophageal reflux symptoms: a meta-analysis. Gut 2018; 67: 430-440.

- Liu L, et al: Relationship between esophageal motility and severity of gastroesophageal reflux disease according to the Los Angeles classification. Medicine 2019; 98:e15543-e15543

- “Down with pain, up with burning: Dysphagia and reflux”, PD Dr. med. Christoph Schmidt, FomF General Medicine Refresher, Cologne, 19.01.2024.

- Gyawali CP, et al: Modern diagnosis of GERD: the Lyon Consensus. Gut 2018; 67: 1351-1362.

- Rusu RI, et al: Validation of the Lyon classification for GORD diagnosis: acid exposure time assessed by prolonged wireless pH monitoring in healthy controls and patients with erosive esophagitis. Gut 2021; 70: 2230-2237.

- Fuchs KH, et al: Foregut symptoms, somatoform tendencies, and the selection of patients for antireflux surgery. Dis Esophagus 2017; 30: 1-10.

- Ness-Jensen E, et al: Weight Loss and Reduction in Gastroesophageal Reflux. A Prospective Population-Based Cohort Study: The HUNT Study. American Journal of Gastroenterology 2013; 108: 376-382.

- Ness-Jensen E, et al: Lifestyle Intervention in Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2016; 14: 175-182.e

- Katz PO, Gerson LB, Vela MF: Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. American Journal of Gastroenterology 2013; 108: 308-328.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2024; 19(2): 34-35 (published on 19.2.24, ahead of print)