At the moment, both dermato-oncologists and allergologists feel addressed by the term “immunotherapy”. Admittedly, the pathways of action of the corresponding therapies from the two disciplines have nothing to do with each other, but “immunotherapy” continues to attract attention in both oncology and allergology. Last fall, for example, a sublingual form of immunotherapy was approved for the first time for house dust mite allergy. In children in particular, exposure prophylactic measures can also be effective, according to a recent report by the American Pediatric Academy.

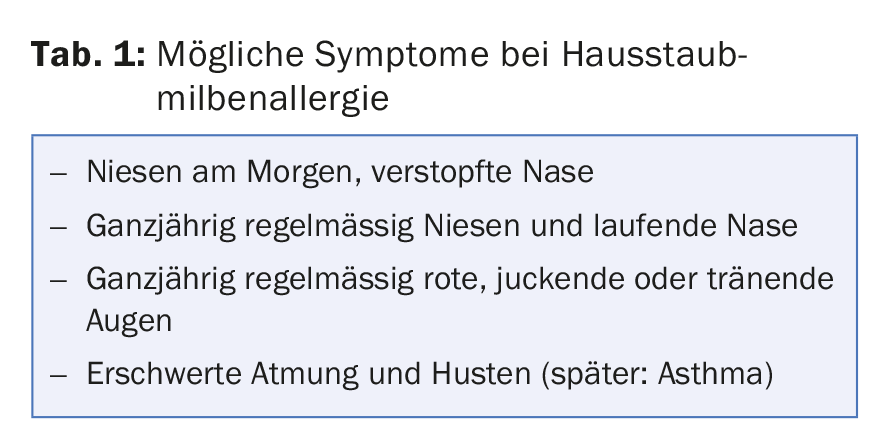

The house dust mite, a genus of mites belonging to the arachnids that likes to live in damp environments, is one of the most common causes of allergies worldwide. Allergens of the two most important species Dermatophagoides farinae and Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus are Der f 1 and Der p 1. Although similarly widespread as grass pollen allergy, house dust mite allergy is much less recognized, which is not least due to the fact that initial symptoms such as morning sneezing and a stuffy nose are not properly classified by the affected persons themselves. The possible signs of the disease in the nose, lungs and eyes increase during the heating period, but are generally found throughout the year (Tab. 1) . The insufficient clarification and associated late diagnosis (often several years pass) cause a high conversion rate to allergic asthma (floor change). Those affected often only receive a diagnosis when the symptoms have already deteriorated decisively.

This is despite the fact that early diagnosis would be crucial for therapy. Compared to pollen allergy, significantly fewer house dust mite allergy sufferers receive specific treatment. The allergic cause of the disease is not recognized or is only treated symptomatically (whereby in many cases moderately severe symptoms remain permanently with corresponding effects on the quality of life). Inadequate treatment threatens exacerbation resulting in allergic asthma.

Specific treatment options – new dosage form approved

Specific immunotherapy (SIT) is the only causal approach in this context. It is based on the (clinically supervised) administration of allergenic proteins. Tolerance to allergens can be achieved through SIT. In addition, the development of new sensitizations and bronchial asthma can be prevented. Basically, SIT is indicated in patients with seasonal and perennial rhinoconjunctivitis allergica (pollen, house dust mites, possibly animal epithelia) and allergic bronchial asthma, if the symptoms cannot be controlled despite drug therapy with e.g. topical steroids as well as topical and systemic antihistamines and exposure prophylactic measures (or if there are contraindications or aversions to the use of corresponding drugs).

Subcutaneous (SCIT) and sublingual (SLIT) preparations are available for performing SIT. While a sublingual form has been approved for grass pollen allergy for some time, the corresponding therapy for house dust mite allergy was still limited to subcutaneous administration until the end of 2016. This may be associated with increased patient inhibition. Since November 2016, a self-administered, sublingual form called Acarizax® has also been available here. Approved is the standardized allergen extract from house dust mites for adult patients (18-65 years) for the treatment of moderate to severe allergic rhinitis, provided that cumulatively the following three conditions are met: Based on the medical history, the symptoms are triggered and maintained by house dust mite exposure, there is positive evidence of sensitization to house dust mites (prick test and/or specific IgE), and the symptoms cannot be adequately controlled despite symptom-relieving therapy [1].

Interventions for exposure prophylaxis

In addition to symptomatic pharmacotherapy and immunotherapy, allergen avoidance or elimination is the third pillar of treatment for allergic diseases. Here, too, there is news or, more precisely, a current catalog of tips from US pediatricians on how to reduce indoor allergens – summarized in a recent report in the journal “Pediatrics” [2]. The focus here is on so-called tertiary prevention, i.e. the aim is to prevent young patients with already manifest asthma from experiencing a worsening of symptoms or long-term course due to contact with certain allergens or pollutants (a comprehensive updated review in the form of an S3 guideline was published about two years ago on the primary prevention of allergy and asthma [3]).

House dust mite allergens have been repeatedly associated with worsening asthma in children with house dust mite sensitization. Conversely, reduction of allergens has shown a corresponding improvement in several studies [4–7]. The study situation is not entirely clear. For the approximately 30-62% of children with persistent asthma who have sensitization to dust mite allergens, it is certainly a possible starting point. The decisive factor is that the allergens and exposure are actually reduced by the measures and that those affected actually suffer from a house dust mite allergy. Only then is there a corresponding effect on asthma, as demonstrated by the most recent meta-analysis on the subject [8]: Of 15 studies in dust mite-sensitized children that included a bed cover as an intervention, 14 measured allergen exposure and seven found at least an 80% reduction. Of these, at least five studies were able to record an improvement in asthma in the intervention group.

As always, the quality of the studies also plays a decisive role. In the review above, there was harsh criticism from the Cochrane authors for this. Admittedly, the design, standardization, and control of experimental conditions in such interventions is challenging.

What interventions are there in the first place?

While pet exposure is relatively easy to determine from the medical history, this is not the case for dust mites, which are invisible to the eye. In part, the indoor climate surveyed can be used to draw such a conclusion (warm and humid, moreover, mites are found more often in rooms with mold). Various test systems and measurement methods are available to actually measure exposure at home, including commercially available measurement kits for self-measurement. Together with the measurement of allergen-specific IgE antibodies in serum or the performance of an allergy skin test, a valuable overall picture is obtained.

When increased exposure is detected, strategies are employed that focus either on removal of the mites themselves or on removal of the allergens, i.e.:

- Bedside interventions (frequent washing of all bedding in hot water; applying a cover/cover to mattress and pillows that are impermeable to allergens, called “encasing”).

- Interventions on other allergen reservoirs (vacuum cleaner, removing carpets and cuddly toys from the bed).

- Use of miticides (acaricides) or allergen-denaturing agents.

The latter measures are cumbersome and proved to be less effective. In addition, there are certain risks associated with the use of chemicals and pesticides in an indoor environment (which is less relevant when used properly, but should be included in the consideration). The reduction of humidity is difficult to achieve and the removal of an integrated carpet can be expensive (again, the benefit is also unclear). Therefore, the authors recommend mainly “encasing” the bed and washing the bed linen regularly. As a “first-line” intervention, these measures are said to be highly effective in reducing dust mite allergens in bed (after all, they feed mainly on dander, which is particularly abundant in bed). Air filtration, on the other hand, would have no relevant effect.

Literature:

- Specialized information on Acarizax®, see swissmedicinfo.ch

- Matsui EC, et al: Indoor environmental control practices and asthma management. Pediatrics 2016; 138(5).

- Schäfer T, et al: S3 Guideline Allergy Prevention – Update 2014. www.%C3%

- Gruchalla RS, et al: Inner City Asthma Study: relationships among sensitivity, allergen exposure, and asthma morbidity. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2005 Mar; 115(3): 478-485.

- Morgan WJ, et al: Results of a home-based environmental intervention among urban children with asthma. N Engl J Med 2004 Sep 9; 351(11): 1068-1080.

- Carswell F, et al: The respiratory effects of reduction of mite allergen in the bedrooms of asthmatic children – a double-blind controlled trial. Clin Exp Allergy 1996 Apr; 26(4): 386-396.

- Halken S, et al: Effect of mattress and pillow encasings on children with asthma and house dust mite allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2003 Jan; 111(1): 169-176.

- Gøtzsche PC, Johansen HK: House dust mite control measures for asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008 Apr 16; (2): CD001187.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2017; 27(1): 26-29