An upside-down stomach, also called a thoracic stomach, is relatively rare. Mostly older people are affected, but not exclusively. It often takes a long time before the correct diagnosis is made and appropriate therapy is initiated. Like the other paraesophageal hernias, the upside-down stomach requires surgical intervention.

Many diseases as causes of dysphagia have already been discussed. Upside-down stomach may be another, certainly not so common, cause of this symptomatology. This change represents the most pronounced form of paraesophageal hernia, which has also been documented previously in this series. The cause of gastric dislocation is a weakness of the ligamentous band apparatus of the gastroesophageal junction.

Defined upside-down stomach is subtotal or total herniation of the stomach into the posterior mediastinum [3,7]. The symptoms are, mostly in older patients, relatively unspecific and thus the correct diagnosis can often be made only late. Shortness of breath, bloating, regurgitation, and retrosternal pressure sensation may also indicate age-related physiologic changes. Iron deficiency anemia, due to malabsorption and chronic mucosal hemorrhage, and syncope are the primary symptoms in about 30% of affected individuals. In extreme cases, the small intestine, colon, or other organs may also herniate and form enterothorax [1,4,9,10]. Bleeding and acute volvulus with obstruction and perforation can also cause the symptoms of acute abdomen.

However, upside-down stomach is not a condition limited to adulthood. Publications on neonatal cases show that intrathoracic volvulus of the stomach can also occur in early infancy [2]. Affected neonates are conspicuous immediately postnatally by respiratory insufficiency; sonographically, a displacement of abdominal organs to intrathoracic is demonstrable [6]. The incidence is approximately 1:2000-5000. Boys are affected twice as often as girls. With more than 90% of the cases, the left side clearly dominates over the right.

X-rays of the thorax in two planes with retrocardiac air collection, sometimes with recognizable secretion, indicate gastric hernia. In enterothorax, the air-containing intestinal loops are also delineable. Oral contrast of the gastrointestinal tract demonstrates the thoracic stomach [5]. It provides information about the positional relationship of the esophagus, cardia, and stomach and the functional situation of the inflow and outflow of the contrast medium. This examination is essential for surgical planning.

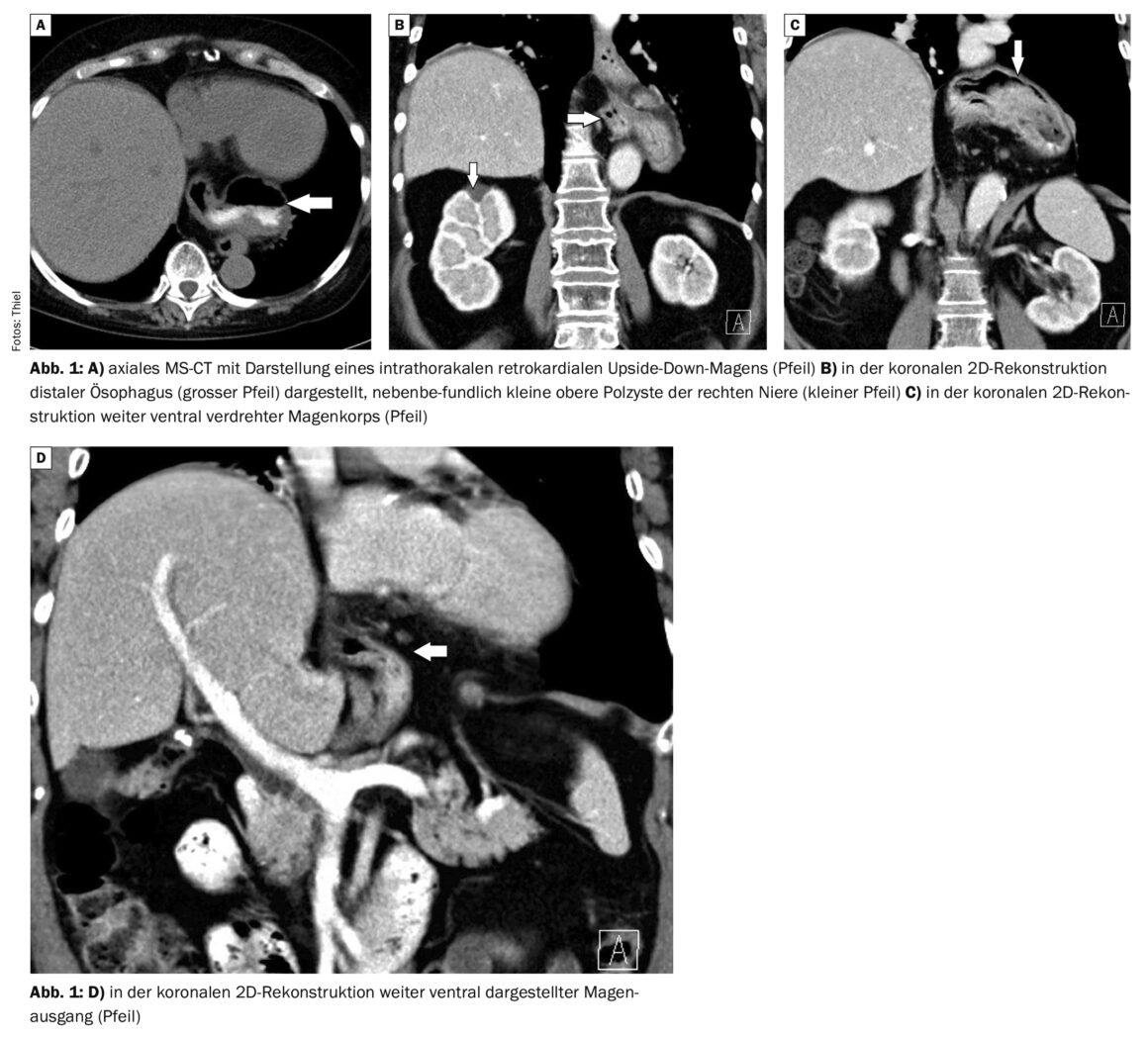

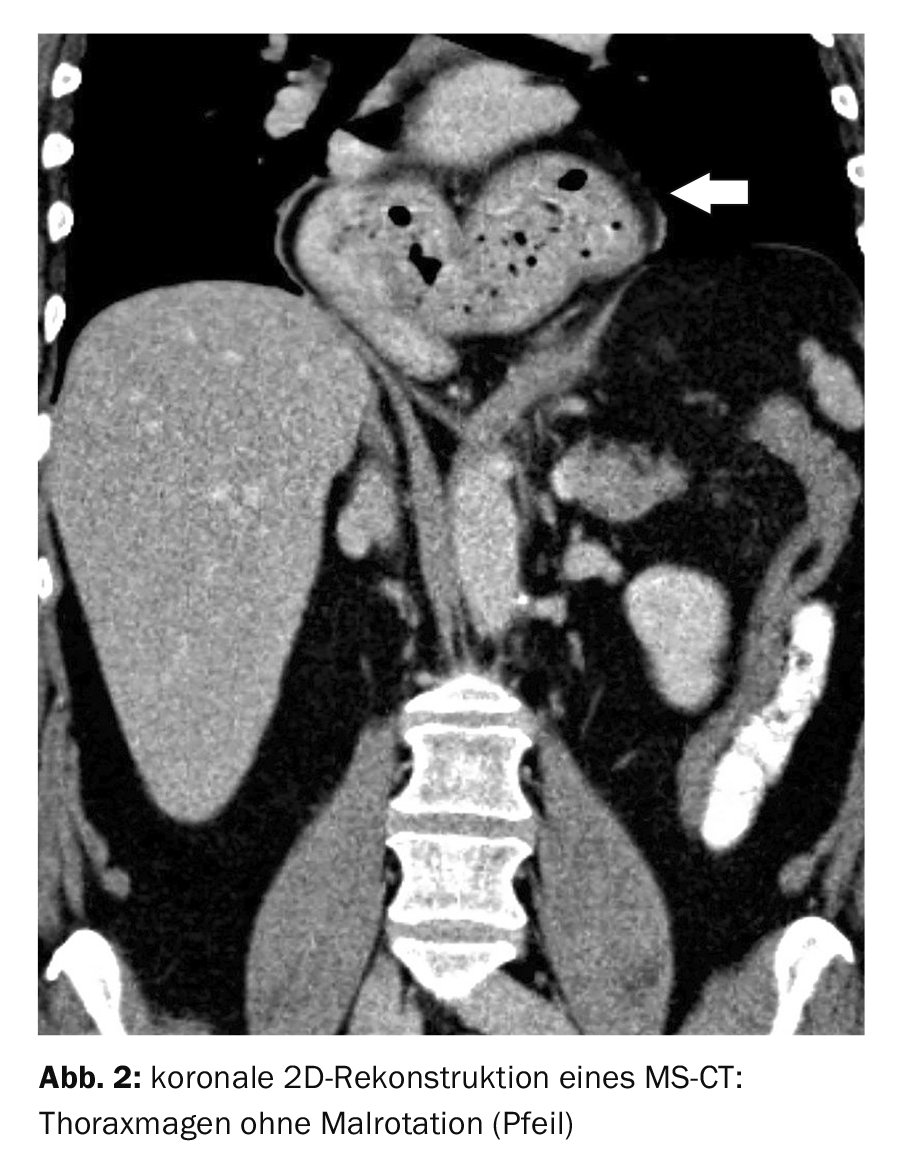

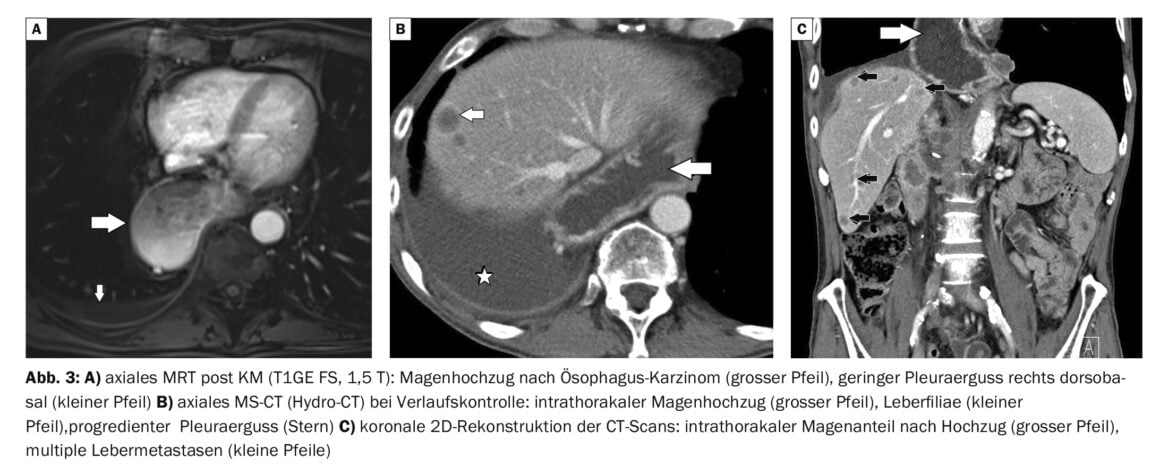

Computed tomographic examinations safely visualize gastric malposition in both axial scans and 2D reconstructions [8]. An advantage of CT is prior oral contrasting with positive (barium sulfate) contrast medium or also with water (hydro-CT) with the advantage of dilating the stomach with better delineation and also functional assessment.

Magnetic reson ance imaging of the positional anomaly of the stomach is also problem-free, the method guarantees the absence of radiation exposure, but has a longer examination time with increased susceptibility to respiratory artifacts.

Case studies

Case report 1 documents an upside-down stomach in a 68-year-old female patient, exhibiting the typical 180° rotation. In the three exemplary 2D coronal reconstructions selected, the feeding esophagus, gastric corpus, and gastric outlet can be well delineated (Fig. 1A to 1D). She complained of a retrosternal feeling of pressure and pain in the upper abdomen. Cholecystolithiasis was also demonstrated (not documented here pictorially).

Case report 2 shows, for comparison, a retrocardiac thoracic stomach with a large diaphragmatic gap in a 62-year-old female patient without the upside-down criteria (Fig. 2).

Case example 3, also for comparison, shows a condition after partial resection of the esophagus for carcinoma with gastric elevation (hydro-CT). Compared with the first two cases, the location of the intrathoracic portion of the stomach is different (MRI, Fig. 3A). Unfortunately, a CT scan 1 year later also revealed a right pleural effusion and hepatic filiae in the 61-year-old patient (Fig. 3B and C).

Take-Home Messages

- Upside-down stomach represents the most pronounced form of paraesophageal hernia.

- It is subtotal or total herniation of the malrotated stomach into the posterior mediastinum.

- In addition to asymptomatic cases, shortness of breath, bloating, regurgitation, and retrosternal pressure sensation may define the clinical symptoms.

- Chronic mucosal bleeding and malabsorption occasionally lead to iron deficiency.

- The change can occur in all age groups.

- Radiological imaging, X-ray examinations or also computed tomography, in each case with oral contrast, offer good detection conditions.

Literature:

- Abboud B, et al: Intrathoracic transverse colon and small bowel infarction in a patient with traumatic diaphragmatic hernia. Case report and review of the literature. J Med Liban 2004; 52(3): 168-170.

- Bawa M, et al: A case of “an upside down stomach”. Hernia 2012; 16(4): 489-492.

- Elzarek A, et al: Colon in the chest: an incidental dextro-cardia: a case report. Case Reports Medicine 2015; 94(6): e507.

- Geissler B, Schäfer P, Anthuber M: Upside-down stomach and thoracic stomach. Diagnosis, surgical indication and technique. CHAZ 2019; 20 (3): 143-147.

- Gupta A, et al: Congenital intrathoracic stomach can be safely managed laparoscopically. Pediatr Surg Int 2020; 36(2): 165-169.

- “Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia,” https://viamedici.thieme.de/lernmodul/8675970/4958922/kongenitale+diaphragmatic-hernia, (last accessed Jan. 13, 2023).

- German Medical Science, www.egms.de, (last accessed Jan. 13, 2023).

- Jain V, et al: Transposed intrathoracic stomach: functional evaluation. Afr J Paediatr Surg 2012; 9(3): 210-216.

- Kohn GP, Price RR, DeMeester SR, et al: SAGES Guidlines Committee (2013). Guidlines for the management of hiatal hernia. Surg Endosc 27: 4409-4428.

- Munteanu AC, Munteanu M, Surlin V, Dilof R. Upside-down stomach and hiatal hernia. Chirurgia (Bucur) 2012; 107(3): 399-403.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2023; 18(2): 42-44