In recent years, a wide range of Internet-based interventions for mental health problems and disorders have been developed. This presentation will provide an overview of the different types of services offered and the current state of research on their effectiveness and acceptance by patients. Specifics, advantages and disadvantages, legal aspects as well as the role of the therapeutic contact and the therapeutic relationship are addressed.

“When I tell colleagues about being involved in e-mental health with a focus on online interventions, many say, ‘That’s definitely the future.’ That future has already begun.” With these words, Prof. Dr. Thomas Berger, University of Bern, introduced his keynote address at the SGPP Annual Congress, citing examples of Internet-based routine practice in psychotherapeutic intervention.

Online interventions are already very common in Sweden. For example, at Karolinska University in Stockholm, Internet Psychiatry – a dedicated department that has developed Internet interventions – has been around for about ten years. Routine patients with mental disorders can choose between conventional psychotherapy and online intervention. The number of patients choosing online intervention increased from an initial 30% to approximately 50% over the past five years [1].

Another example: In Australia, there is the government-funded, virtual MindSpot Clinic. The public can access free online self-study interventions for anxiety disorders and depression.

The Netherlands also relies on Internet-based support. Currently, 70% of psychotherapy/psychiatric institutions combine conventional psychotherapy with Internet-based interventions [2]. This means that face-to-face psychotherapy and online intervention are conducted in an interlocked manner.

The different approaches in the countries are clear: In Sweden, patients are first diagnosed in a face-to-face interview. You must appear in person. If there is a tool for the diagnosed disorder, the patient can choose. In Australia, there is no face-to-face meeting for diagnostics either, but telephone interviews are integrated into the concept. In the Netherlands, patients keep meeting therapists during the online intervention.

Status Switzerland

For the last two years or so, psychiatries have been very interested in the topic of e-mental health. The Swiss Psychology Federation FSP presented for the first time at the SGPP the “Quality Standards for Counseling and Therapeutic Activities on the Internet” [3], recently approved by the Board. Health insurance companies have begun offering such interventions. The general trend toward digital solutions only partly accounts for these developments. It’s a well-known problem: in the population, one-third of people develop a mental disorder within a year. Even in Switzerland, which has a very good care system, at most half seek professional help at [4,5]. Internet interventions can reach more people.

What is Internet Intervention?

On the one hand, digital media offer communication possibilities via e-mail, chat, video telephony. “We now know that therapists are increasingly emailing or skyping with patients, although the research is scarce here,” the speaker pointed out. Self-help programs, self-learning content, or apps that do not involve contact with clinics are also used to provide helpful information.

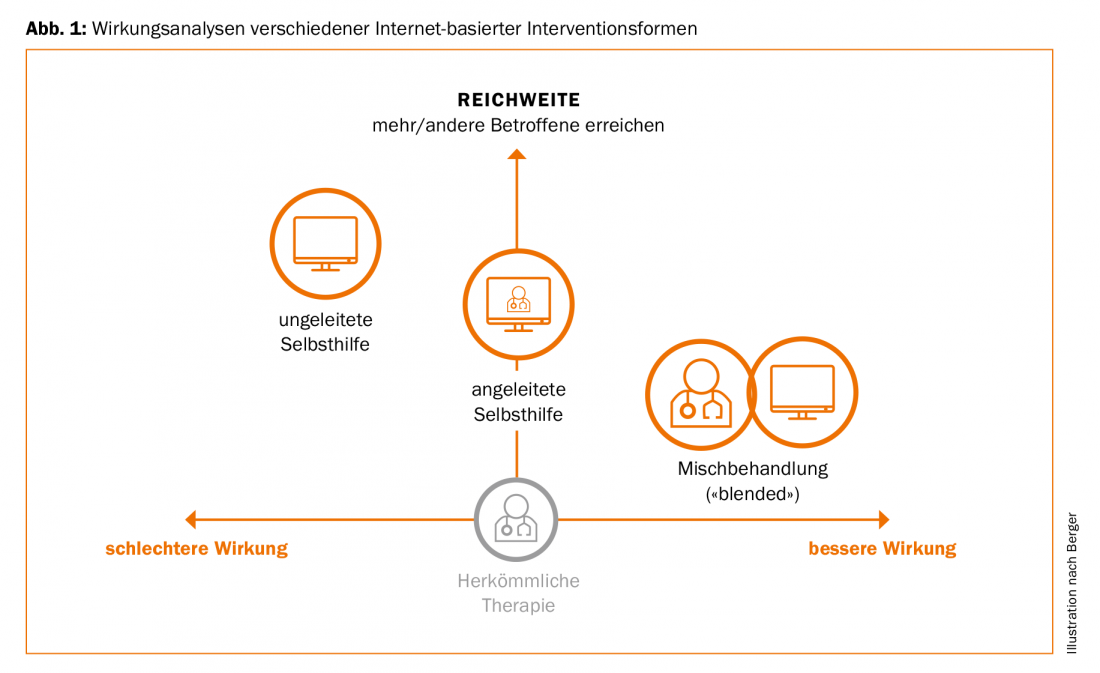

The combination of a self-help program and personal care is called guided self-help. This means that patients get access to self-help tools while being supported by therapists via email. Blended treatments are Dutch-style treatments that mix regular face-to-face meetings with self-help applications. These forms are also the most researched today, Berger said.

These self-help programs are mimics of disorder-specific therapies. Sessions are held, patients have to work through certain modules in a certain time, there is homework, there is psychoeducation, exercises or regular assessments. This usually provides patients and therapists with feedback on symptoms and changes. Many applications can now also be used via cell phone (M-Mental-Health). Typically, these solutions are in a screen-neutral “responsive design”. Therapists have an overview of patients and their completed sessions, mood barometers or assessments via the so-called therapist cockpit.

State of research on the effect

For mixed treatments, there are still few studies that are controlled randomized. This means that in the Netherlands a model has been adopted in routine care that has not been empirically proven. In a pragmatic randomized trial conducted with the German Psychotherapists Association [6], depression inventory after twelve weeks and six months of treatment with additional Internet intervention was significantly lower than with conventional psychotherapeutic treatment. As a mixed treatment, the therapy was more effective.

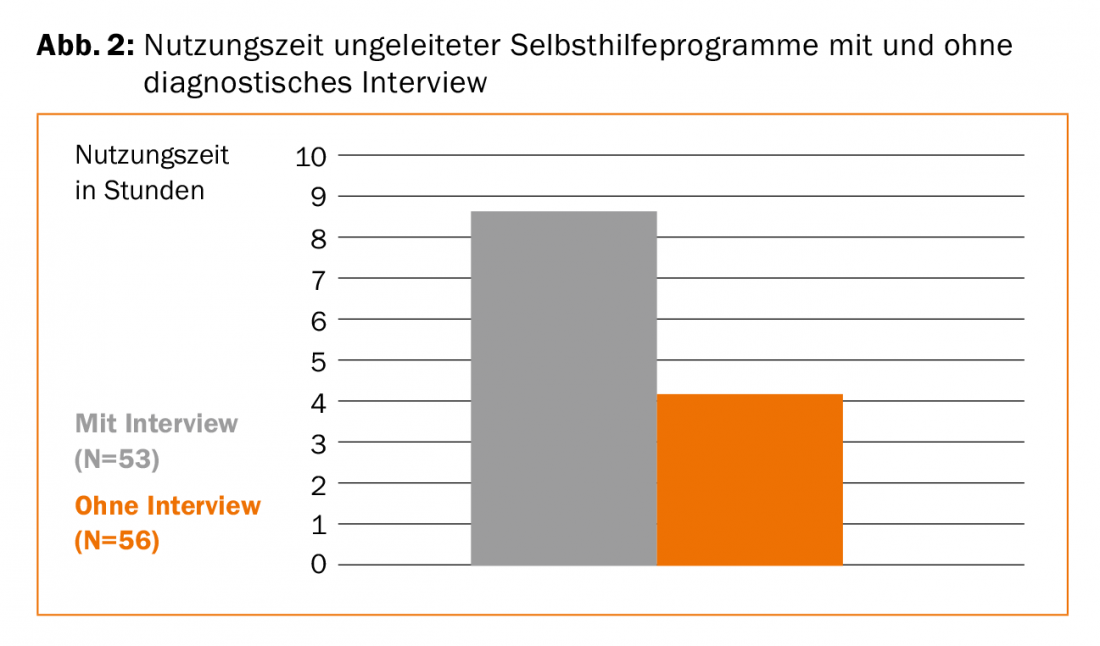

For unguided and guided self-help programs and apps, the study situation is quite different. The number of efficacy studies have increased exponentially in recent years to more than 200; meta-analyses also exist. These often showed a similar picture, the speaker elaborated. The unguided self-help programs were often less effective and participants were more likely to drop out [7]. Guided programs are comparably effective as conventional therapies. Direct comparisons have also been made in various disorders, and most studies are available on anxiety disorders and depression. Five-year analyses showed that changes were maintained (currently several meta-analyses). The effectiveness of self-help programs with or without contact (i.e., guided or unguided) is markedly different: only small effects are generated without a diagnostic interview [8]. These increase when there is no diagnostic interview but there is monitoring. When an interview takes place and accompaniment is present, effectiveness is highest. In summary: Effectiveness increases the more personal interaction takes place. This is also shown by our own study [9]: In anxiety disorder patients, the utilization time of an unguided self-help program was twice as long in patients who received a face-to-face diagnostic interview as in patients without an interview (Fig. 2). Thus, the context in which such programs are administered, i.e., diagnostic interviews, clinic contact, etc., appears to have consequences for their effectiveness.

Opportunities for Internet-based intervention

Many therapists have a deficit-oriented view and reject Internet-based interventions wholesale because of psychological distance, reduced or lack of immediacy of exchange. Berger points out, however, that these deficits are also compensated for. For example, patients have been found to communicate their feelings more when they write [10]. Also, there is a greater openness of patients when they communicate with the therapist via the Internet [11]. They get to the point faster. A common question concerns the therapy relationship. Here, studies using the same measurement tools show that patients and therapists rate them equally. However, this research does not examine specific aspects of the online relationship. Therapy outcome research is inconsistent: therapy relationship varies in importance by patient and disorder. For some people, the relationship is much more important than for others – another open research topic.

Challenges and outlook

To date, online interventions have been developed at individual institutions. Since there were no regulations, it was possible to act very quickly. There are countless studies that show the effectiveness of Internet-based intervention. However, implementation in routine practice has not yet taken place. So far, you can’t assign patients who ask. Clarifications on legal, data security and quality standards aspects have been taking place for about two years now.

Overview URLs

- Internet Psychiatry Sweden

http://web.internetpsykiatri.se - MindSpot Clinic, Australia

https://mindspot.org.au - Silicon Valley startup Joyable

https://joyable.com

Source: SGPP Annual Congress, 13-15.09.2017, Bern

Literature:

- Statement of the speaker

- Ruwaard J, Kok RN: Wild west eHealth: Time to hold our horses? European Health Psychologist 2015; 17; 45-49.

- Position Paper Psychiatric Service Delivery through Modern Communications, FMPP July 2017, www.psychiatrie.ch/fmpp/stellungnahmen-und-publikationen/positionspapiere-und-stellungnahmen-fmpp

- Kessler RC, et al: The global burden of mental disorders: an update from the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) surveys. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences 2009; 18 (1): 23-33.

- Stocker D, et al: Versorgungssituation psychisch erkrankter Personen in der Schweiz. Büro für arbeits- und sozialpolitische Studien BASS 2016.

- Krieger T, et al: Evaluating an e-mental health program (“deprexis”) as adjunctive treatment tool in psychotherapy for depression: design of a pragmatic randomized controlled trial. BMC psychiatry 2014; (14) 1: 285.

- Hedman E, Ljótsson B, Lindefors: Cognitive behavior therapy via the Internet: a systematic review of applications, clinical efficacy and cost-effectiveness. Expert review of pharmacoeconomics & outcomes research 2012; 12 (6): 745-764.

- Johansson R, Andersson G: Internet-based psychological treatments for depression. Expert review of neurotherapeutics 2012.

- Boettcher J, Berger T, Renneberg, B: Does a Pre-Treatment Diagnostic Interview Affect the Outcome of Internet-Based Self-Help for Social Anxiety Disorder? A Randomized Controlled Trial. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy 2012; 40 (5): 513-528. doi:10.1017/S1352465812000501

- Berger T: Internet-based interventions for mental disorders. Hogrefe Verlag, Bern 2015.

- Suler J: The online disinhibition effect. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2004; 7 (3): 321-326.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2017; 15(6): 43-45.