After ischemic stroke of noncardioembolic etiology: early aspirin treatment is extremely effective in preventing recurrence. Atrial fibrillation should be treated with one of the new oral anticoagulants because of the more favorable benefit-risk profile. Control of blood pressure and lipid status remain cornerstones of secondary prevention. New promising lipid-lowering agents of the PCSK9-AK class are currently undergoing clinical trials. Symptomatic ICA stenoses: fastest possible clarification and therapy within an interdisciplinary treatment setting.

Permanent disability and loss of independence in everyday life are catastrophic consequences of a stroke for those affected and their relatives. About 150 out of 100,000 people suffer a stroke per year in Switzerland; 20-30% of these are recurrences. Fortunately, the number of deaths from stroke in Switzerland has decreased significantly in recent years; worldwide, the incidence is decreasing in people over 60 years of age of Caucasian origin. Significant advances in the acute treatment of stroke patients and in the management of typical complications are reducing mortality. Fewer new cases were achieved by improving secondary prevention. Good and effective secondary prevention is not equally accessible to all people because of the unavailability or poor availability of medicines and the lack of widespread education. Therefore, stroke rates are increasing in some regions, such as Latin America or the Middle East [1,2].

Secondary prevention after ischemic stroke is based on several pillars: risk factor modification and secondary prophylaxis with medication. Measures and important new developments are summarized below.

Antiplatelet agents (TAH)

Antiplatelet agents represent the basis of secondary drug prevention of noncardioembolic strokes. The benefit of aspirin, especially in early secondary prevention, was impressively demonstrated in a recently published meta-analysis (over 15,000 patients): the risk of stroke recurrence in the first six weeks is reduced by approximately 60% by early aspirin administration [3]. The effect is most pronounced after TIA and milder strokes. However, the known long-term benefit of ASA is much lower (approximately 10% risk reduction). After an ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA), aspirin should be started as soon as possible at a dose of 100 mg/d. If oral intake is not possible, this should be done intravenously or via a nasogastric tube. There is less evidence for dipyridamole+ASS and clopidogrel; however, a similar secondary preventive effect can be assumed, so these substances can be considered as second-line agents after ASA or in case of recurrence under ASA. However, there are no studies showing superiority of this approach compared with maintaining ASA. It is important to thoroughly search again for the cause of stroke after a recurrence and especially to exclude intermittent atrial fibrillation [4].

Based on positive results from CHANCE (data collected in China in patients with mild stroke symptoms) and SAMMPRIS (patients with intracranial vascular stenosis), dual antiplatelet therapy with ASA 100 mg/d and clopidogrel 75 mg/d may be temporarily considered in certain patient populations [5,6]. Despite the good effect during a short treatment period in the acute phase, one should not lose sight of the increased risk of bleeding in long-term dual therapy. In certain stroke subtypes such as microangiopathic (“lacunar”) insults, no benefit of dual therapy was shown; the risk of bleeding increased significantly [7]. The TAH ticagrelor was recently tested against aspirin in early secondary prophylaxis for noncardioembolic mild stroke or TIA (SOCRATES trial), showing a trend toward reduction in stroke but no superiority [8].

Anticoagulation

To date, no clinical trial demonstrates that anticoagulation is superior to aspirin therapy in the acute phase after cardioembolic stroke because any potential benefit is outweighed by an increased risk of bleeding [9]. It is crucial to accurately select those patients who could benefit. However, in patients with atrial fibrillation or another cardiac source of embolism with a high risk of embolism, anticoagulation in the acute phase may be considered under benefit-risk assessment, depending on the size of the insult and other comorbidities (age, vascular leukoencephalopathy, diabetes, other sources of bleeding). Initially, continuous heparin infusion is preferred over other forms of anticoagulation because of its good controllability. Because of their favorable benefit-risk profile, the new anticoagulants (DOAKs) such as dabigatran (direct thrombin inhibitor), rivaroxaban, apixaban, and edoxaban (factor Xa inhibitors) are increasingly used directly for smaller lesions or TIAs. DOAKs are at least equivalent to Marcoumar for the prevention of systemic embolism and have a significantly lower risk of bleeding, especially intracranial bleeding. Therefore, when nonvalvular atrial fibrillation is detected as a cause of stroke, these agents should be used primarily. The four DOAKs currently approved in Switzerland have somewhat different pharmacodynamic profiles. Renal function, patient age, co-medication, and gastrointestinal history should be considered when choosing a DOAK. TAH should be prescribed for secondary prevention of stroke or TIA with atrial fibrillation only when an alternative (eg, cardiac) indication exists. In the AVERROES trial, it was shown that even patients in whom bleeding complications were considered too high for the prescription of vitamin K antagonists benefited significantly from the DOAK apixaban compared with aspirin, without suffering significantly more bleeding complications. If the risk of bleeding is still considered too high, atrial ear closure may be considered [10].

Hypertension

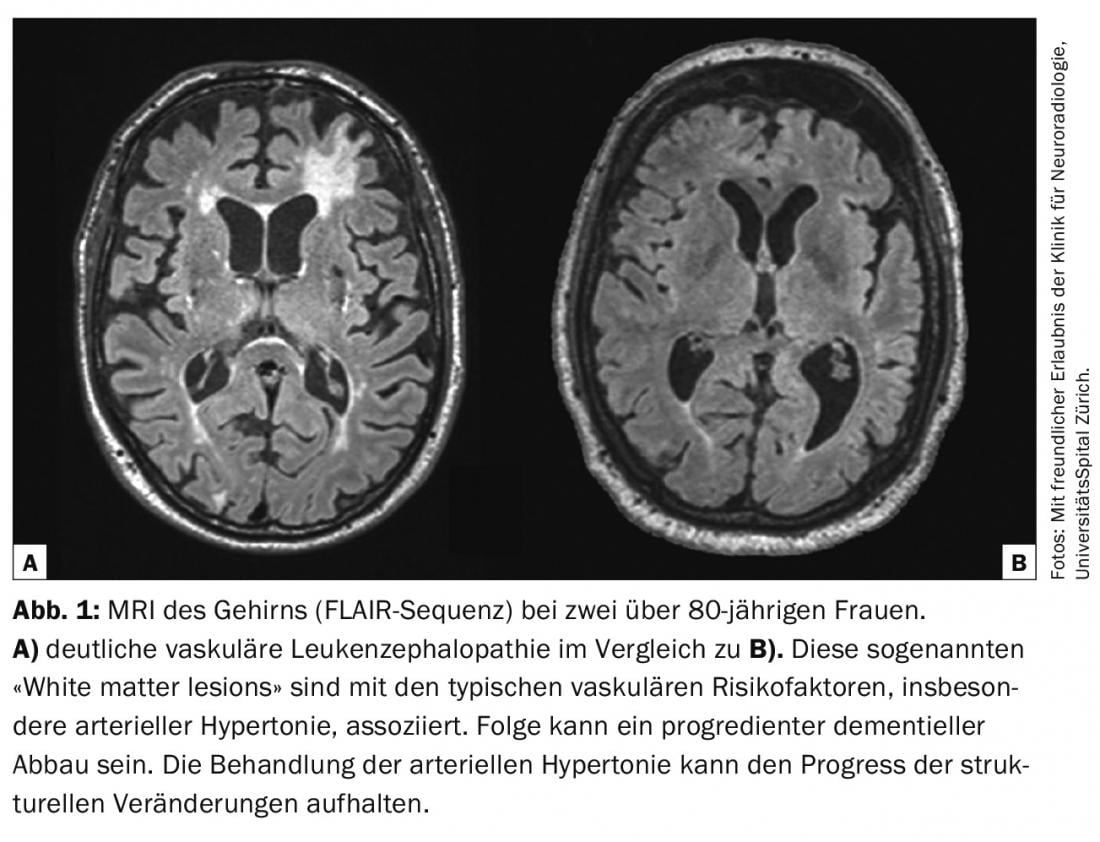

While the optimal blood pressure setting in the acute phase is currently controversial, the benefit of normotensive blood pressure levels (systolic <140 mmHg and diastolic <90 mmHg) during the course is well established. Blood pressure reduction by an average of 10 mmHg systolic and 5 mmHg diastolic triples the recurrence risk for ischemic insult. The effect is independent of pre-existing arterial hypertension and cause of stroke. Which drug or non-drug measure leads to the achievement of the target blood pressure value does not play a decisive role (Fig. 1).

Lipid status and nutrition

Dyslipidemia, especially in the constellation of high LDL cholesterol and triglyceride levels, is associated with the progression of atherosclerotic changes in the vessels. In patients <75 years of age with ischemic stroke and typical atherosclerotic risk constellation, LDL cholesterol should be lowered to <50% of baseline, in other stroke patients to <30%; primarily by statins. Prescribed LDL target values are controversial; current guidelines suggest an LDL cholesterol of less than 2.6 mmol/l. Statins reduce mortality and the incidence of cardiovascular events. Based on the results of the SPARCL trial, many centers start high-dose atorvastatin in the first days after stroke. In addition to the cholesterol-dependent effect, plaque-stabilizing effects are probably also achieved by early administration of statins. Statins are not used in patients with hemorrhagic infarcts because several studies have shown an increased incidence of bleeding complications. However, it is important that even in these patients, preexisting treatment with statins, e.g., for cardiac indications, is not interrupted in the event of a stroke. An exciting development in the field of lipid lowering is the introduction of proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) antibodies such as evolocumab. Initial study results demonstrated a highly effective reduction in LDL and, in a still short follow-up, a reduction in cardiovascular events [11]. In addition to medication, a balanced Mediterranean diet has a positive effect on lipid status, hypertension, and overall risk of cardiovascular disease.

Carotid stenosis

Stroke patients with high-grade, symptomatic stenosis of the internal carotid artery (ICA) have a particularly high risk of recurrence. From the large randomized trials NASCET and ECST, this is estimated to be approximately 16% per year. Therefore, carotid endarterectomy (TEA) is recommended for symptomatic ICA stenoses of >70% according to NASCET criteria (five-year risk reduction: 61%). In 50-60% stenoses, this is also a reasonable option with lower five-year risk reduction of approximately 25%. In asymptomatic ICA stenoses, the benefit of TEA is in selected high-risk cases. However, since the era of NASCET and ECST (1980s), drug treatment with TAH, statins, and antihypertensives has improved to the point that we can assume that not only asymptomatic but also symptomatic ICA stenoses have reduced the risk of recurrent stroke. Stenting of the ICA is an alternative to TEA for younger patients, re-stenting of a previously operated ICA, or an increased surgical risk due to cardiac or pulmonary disease. The decision to intervene (carotid TEA or stenting) should be made on an interdisciplinary basis. If infarct size and comorbidities permit, intervention should be performed as early as possible, because the risk is significantly higher in the first 14 days than in the weeks thereafter [12].

Literature:

- Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, et al: Heart disease and stroke statistics–2015 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2015; 131: e29-322.

- Andreani T, et al: Health Statistics 2014. Neuchâtel: Swiss Federal Statistical Office, 2014.

- Rothwell PM, et al: Effects of aspirin on risk and severity of early recurrent stroke after transient ischaemic attack and ischaemic stroke: time-course analysis of randomised trials. Lancet 2016; May 18. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30468-8 [Epub ahead of print].

- Diener HC, Frank B, Hajjar K, Weimar C: [New aspects of stroke medicine]. Neurologist 2014; 85: 939-945.

- Wang Y, et al: Clopidogrel with aspirin in acute minor stroke or transient ischemic attack. N Engl J Med 2013; 369: 11-19.

- Chimowitz MI, et al: Stenting versus aggressive medical therapy for intracranial arterial stenosis. N Engl J Med 2011; 365: 993-1003.

- SPS3 Investigators, Benavente OR, Hart RG, et al: Effects of clopidogrel added to aspirin in patients with recent lacunar stroke. N Engl J Med 2012; 367: 817-825.

- Johnston SC, et al: Ticagrelor versus aspirin in Acute Stroke or Transient Ischemic Attack. N Engl J Med 2016; May 10 [Epub ahead of print].

- Paciaroni M, Agnelli G, Micheli S, Caso V: Efficacy and safety of anticoagulant treatment in acute cardioembolic stroke: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Stroke 2007; 38: 423-430.

- Holmes DR, et al: Percutaneous closure of the left atrial appendage versus warfarin therapy for prevention of stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation: a randomised non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2009; 374: 534-542.

- Sabatine MS, et al: Efficacy and Safety of Evolocumab in Reducing Lipids and Cardiovascular Events. New Engl J Med 2015; 372: 1500-1509.

- Johansson E, et al: Recurrent stroke in symptomatic carotid stenosis awaiting revascularization A pooled analysis. Neurology 2016; 86: 498-504.

CARDIOVASC 2016; 15(4): 4-6