In progressive forms and extensive linear expression of the lesions, deformities and movement restrictions may occur if left untreated. Early diagnosis enables adequate treatment measures and sustainable long-term management. This is not trivial and requires individualized clarification and follow-up.

In particular, the most common form in childhood, the progressive linear subtype, carries a significant risk of complications [1]. “It is a disease that progresses if left untreated and can lead to severe deformities and contractures, especially in the extremities,” explained PD Lisa Weibel, MD, Chief of Dermatology at the Children’s Hospital Zurich, at this year’s virtual ZDFT Annual Congress [2]. The exact causes of circumscritic scleroderma are not yet known; in addition to genetic predisposition and trigger factors such as trauma, vaccination, and infection, involvement of the immune system is also discussed.

Diagnostic latency can be momentous

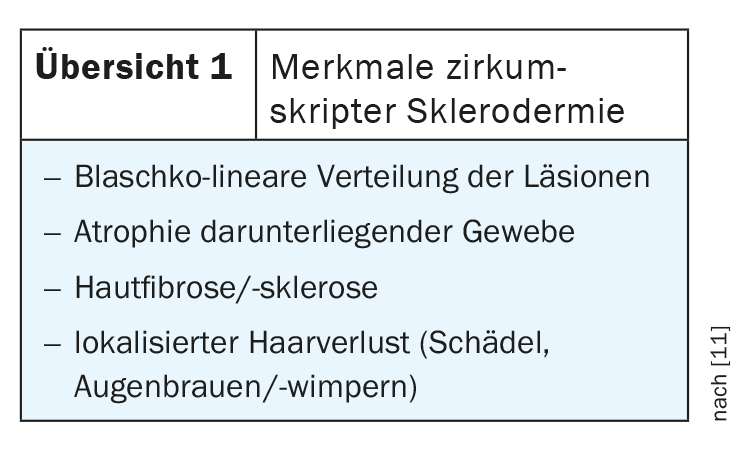

Timely diagnosis is essential to avoid missing the “window of opportunity” for forms of the disease that require treatment. The main clinical features of circumscritic scleroderma include a Blaschko-linear distribution of lesions, atrophy of underlying tissues, skin fibrosis/sclerosis, and localized hair loss (skull, eyebrows/eyelashes) (Overview1). “Morphea can initially manifest with white patches or sclerotic plaques, which can be discrete or, for example, in the extremities, very extensive,” the speaker explained. Other early manifestations include irritation of a capillary malformation (port-wine stain-like skin change).

Circumscribed scleroderma can occur from birth, especially “en coup de sabre” lesions, which manifest as localized alopecia with central inflammatory skin changes after a few months. Congenital morphea are rarely diagnosed in time. Many of the affected infants have neurological abnormalities and musculoskeletal sequelae. “On average, we expect a diagnostic delay in infancy of 1 year,” the speaker added, “and in individual cases, significantly more.

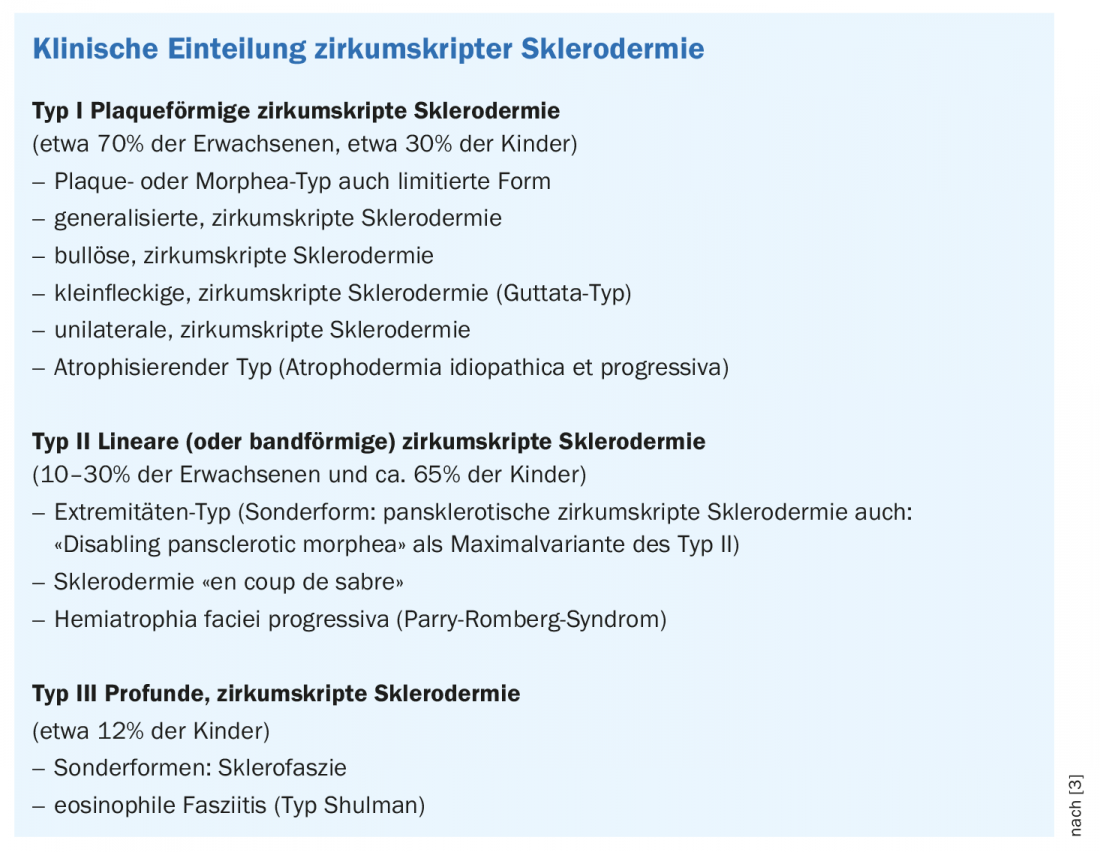

Depending on the type, size, and location of sclerotic connective tissue induration, three to four different clinical types and several special forms of circumscritic scleroderma are distinguished (Box) [3]. The two main groups are plaque and linear (ribbon) circumscritic scleroderma. The linear subtype is most common in childhood and affects not only the dermis but also the underlying tissues such as the subcutis, musculature, and skeleton [4]. Uveitis and joint pain are among the common extracutaneous symptoms. Linear indentations can occur, particularly in the facial region, which can cause significant deformity and atrophy.

In case of head infestation: imaging techniques

Neurologic complications occur in 10-20% of patients with “en coup de sabre” lesions. Therefore, if the face or scalp is involved, an MRI examination with contrast agents should be performed and repeated each time new neurologic symptoms occur, an expert panel concluded [5]. The most common neurological symptoms include headaches and migraines. Occasionally, seizures, hemiparesis, and discrete personality changes or intellectual deterioration occur. It is important to keep in mind that 80% of affected patients have abnormal MRI findings, Dr. Weibel emphasizes.

What should be considered in terms of differential diagnosis ?

While symmetrically expressed white patches without any atrophy indicate initial non-segmental vitiligo in childhood, whitish patches with some sclerotic aspect as well as indentation in the area of the chin and asymmetry of the face with discrete fascial hemiatrophy are classic features for scleroderma “en coup de sabre”. A differentiation from Parry-Romberg syndrome, which was originally understood to mean hemifacial atrophy in the middle region of the face , while only lesions in the region of the forehead were assigned “en coup de sabre”, is no longer relevant today,

there is a broad consensus that these two clinical manifestations do not need to be differentiated with regard to therapy, the speaker explained.

Based on a case report of an adolescent with multiple bilateral morphea lesions in the area of the lower legs, the lecturer demonstrated a further differential diagnostic delimitation. In this case, detailed histologic workup revealed granuloma anulare. A distinguishing feature is hair growth in the area of the lesion, which is atypical for localized scleroderma.

Linear morphea: stopping inflammation with systemic treatment

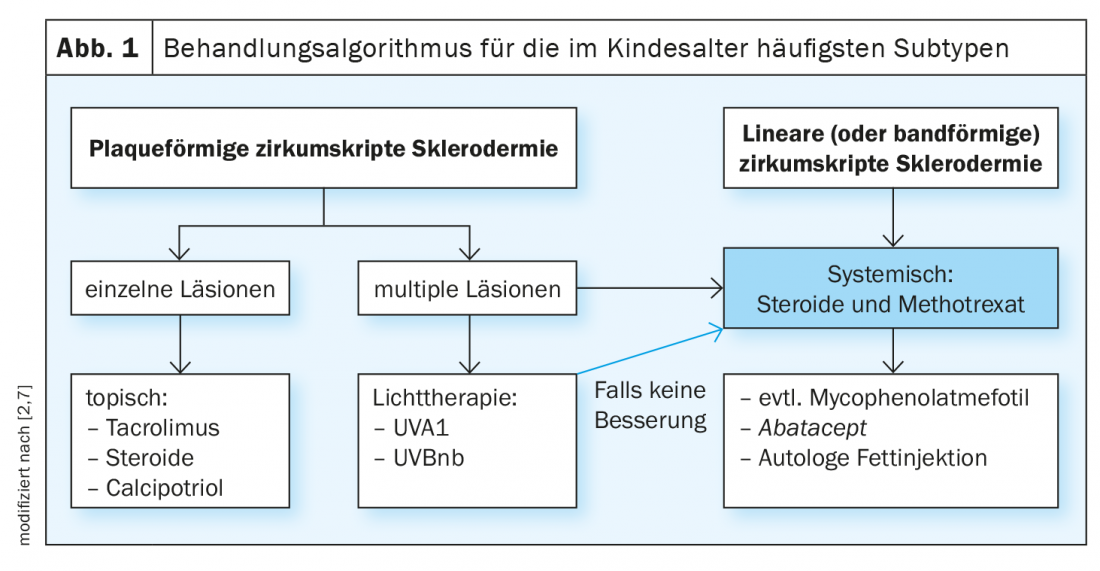

First and foremost, the treatment goal is to control inflammation and thus bring about a reduction in scar tissue. The choice of therapy is individualized, taking into account the severity of the symptoms and the course of the disease. There are cases in which the inflammation and sclerosis resolve on their own, but especially if the disease takes a more severe course, systemic therapy may be necessary. A secondary analysis found that delayed initiation of treatment resulted in a longer period of disease activity and was associated with higher recurrence rates [6]. It also showed that most tissue damage occurs at an early stage of disease. “We have good treatment recommendations and sound therapies,” she said. These largely correspond to the treatment algorithm of the 2017 updated European guidelines (Fig. 1) [7]. A distinction is made between limited superficial morphea (plaque type), which can be treated topically or in combination with light therapy, and a linear pansclerotic subtype with band-like lesions.

First-line therapy: In linear morphea, methotrexate is considered the gold standard first-line therapy, usually in combination with systemic steroids. This is an evidence-based treatment option, as also confirmed by current findings. A prospective study published in 2020 demonstrated that disease activity decreased significantly over an 18-month treatment period, and other recently published data attest to high remission rates for standard treatment with steroids and methotrexate [8–9]. “Methotrexate is very central to the treatment of the disease,” Dr. Weibel said. The dosage recommendation for methotrexate is 15 mg/m2/week (max. 25 mg), the dosage form is ideally subcutaneous, sometimes oral. When combined with folic acid, a dosage of 1 mg on 6 days per week is more recommended than 5 mg once weekly with regard to gastrointestinal side effects/nausea. Steroids are used particularly in progressive disease and marked sclerosis or inflammation. Standard practice is to use intravenous methylprednisolone 30 mg/kg per infusion, up to a maximum dosage of 500mg in children, on 3 consecutive days each month for a period of 3 months. Alternatively or in addition, oral prednisolone 0.7-1.5 mg/kg/d may be used for 2-4 weeks and phased out over 3-6 months. Rheumatologists tend to prescribe steroids for a longer period of time, sometimes up to a year, the speaker said.

Second-line therapy: Abatacept is recommended as second-line treatment. In a case series published in 2018, a reduction in lesion size and overall symptom severity was observed and, in general, treatment was found to be well tolerated [10]. Mycophenolate mefotil is mentioned as another second-line option in the treatment recommendations.

Complementary therapeutic measures: Plastic surgical methods (especially autologous fat injection) should be offered as an adjunct to anti-inflammatory treatment. In parallel with first- or second-line treatment, physiotherapeutic measures are an important aspect, especially in linear scleroderma. If leg length discrepancies occur, shoe inserts can be helpful to compensate for the difference in length.

Literature:

- Weibel L: Localized scleroderma (morphea) in childhood. Der Hautarzt 2012; 63: 89-96.

- Weibel L: Morphea – Localized Scleroderma: my 5 golden rules. PD Lisa Weibel, MD, Zurich Dermatology Continuing Education Days (ZDFT), May 14-15, 2020.

- Altmeyer’s Encyclopedia, www.altmeyers.org/de/dermatologie/sklerodermie-zirkumskripte-ubersicht-3722

- German Center for Child and Adolescent Rheumatology, www.rheuma-kinderklinik.de

- Constantin T, et al: Development of minimum standards of care for juvenile localized scleroderma. Eur J Pediatr 2018; 177(7): 961-977.

- Martini G, et al: Disease course and long-term outcome of juvenile localized scleroderma: Experience from a single pediatric rheumatology Centre and literature review. Autoimmunity Reviews 2018; 17(7): 727-734.

- Knobler R, et al: European Dermatology Foum S1-guideline on the diagnosis and treatment of sclerosing diseases of the skin, Part 1: localized scleroderma, systemic sclerosis and overlap syndromes. JEADV 2017; 31(9): 1401-1424.

- O’Brien JC, et al: Changes in Disease Activity and Damage Over Time in Patients With Morphea. JAMA Dermatol 2020; 156(5): 513-520.

- Weibel L, et al: Prospective evaluation of treatment response and disease reversibility of paediatric localized scleroderma (morphoea) to steroids and methotrexate using multi-modal imaging. JEADV 2020; 34(7): 1609-1616.

- Wehner Fage S, et al. : Abatacept Improves Skin-score and Reduces Lesions in Patients with Localized Scleroderma: A Case Series, www.medicaljournals.se/acta/content/html/10.2340/00015555-2878

- Weibel L, et al: Misdiagnosis and delay in referral of children with localized scleroderma. BJD 2011; 165(6): 1308-1313.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2020; 30(6): 51-52 (published 7/12/20, ahead of print).