Actinic or solar keratoses represent in situ squamous cell carcinomas of the skin and are one of the more common dermatoses in daily practice. On the one hand, it is necessary to educate the patient about the significance of his chronic photodamage to the skin, the onset of carcinogenesis, the likely lifelong follow-up examinations, and the treatments to be performed at times more or less. On the other hand, different methods can be offered, ranging from short and violent to long and moderate, from self-administered to physician-applied. Also, it may be necessary to switch from one method to the other or combine one with the other. The following article discusses the many possibilities.

As the name suggests, the sun resp. UV radiation is responsible for the development of actinic or solar keratoses. In particular, chronic UV exposure leads to permanent and increased DNA and genome damage of the skin, the consequence of which is then a more or less pronounced mitosis-rich proliferation of transformed dyskeratotic keratinocytes. It is estimated that 10% of the affected patients (some authors talk about 15-20%) develop invasive squamous cell carcinomas from actinic keratoses in the untreated further course. With additional drug immunosuppression, e.g. as a result of organ transplantation, the risk of carcinoma is 30%.

Furthermore, the development of actinic keratoses is related to skin type and intensity of UV exposure. Therefore, much higher prevalences are observed in regions with high UV irradiation and fair-skinned population. In our latitudes, actinic keratoses are found in 11-25% of people over 40 years of age, whereas in Australia the rate is 60%. According to a recent study from Hamburg, the overall prevalence is 2.7%, with men still more affected at 3.9% than women at 1.9%. Furthermore, it could be shown that the older the patients were, the more frequently actinic keratoses occurred.

Clinical findings

Actinic keratoses present as skin-colored reddish or reddish-brownish rough, scaly macules, papules, or plaques, especially on UV-exposed skin areas such as the capillitium, ear helix, nose, forearms, or dorsum of the hands (Fig. 1) .

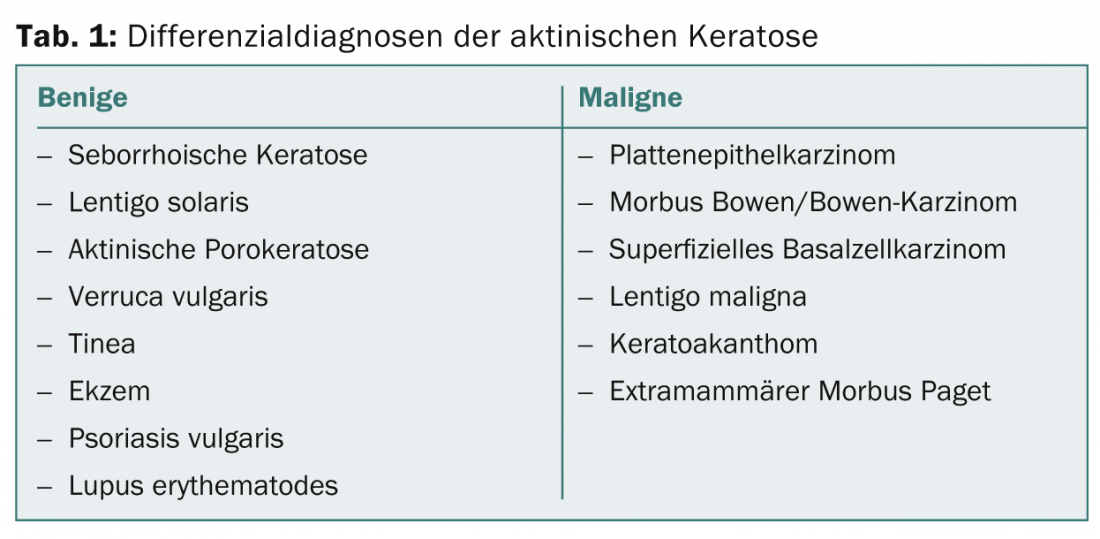

Rarely do individual lesions occur; rather, an entire region is affected, which is why one then speaks of field cancerization. Differential diagnoses are in Table 1.

Diagnostics

The diagnosis is usually made on the basis of the typical clinical picture or the clinical signs. of the characteristic rough palpation. However, in case of doubt and especially in hypertrophic actinic keratoses to differentiate them from squamous cell carcinoma, a biopsy is necessary. Two studies from 2011 are interesting in this regard, one showed that tenderness was a significant discriminant for the presence of squamous cell carcinoma. The other study focused on dermatoscopic discrimination criteria. It was found that actinic keratoses present mainly a red pseudonetwork and slightly yellowish-brownish scales, whereas invasive carcinomas present hairpin and irregular vessels, targoid hair follicles, central keratin masses and ulcerations.

Therapy

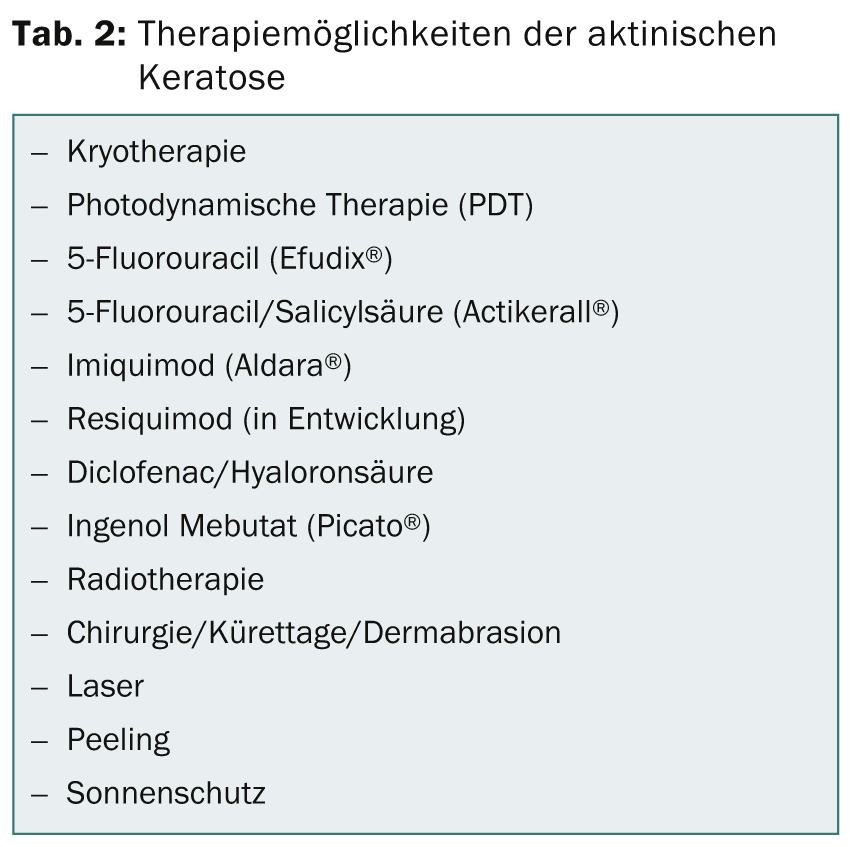

A variety of treatment options are currently available (Table 2).

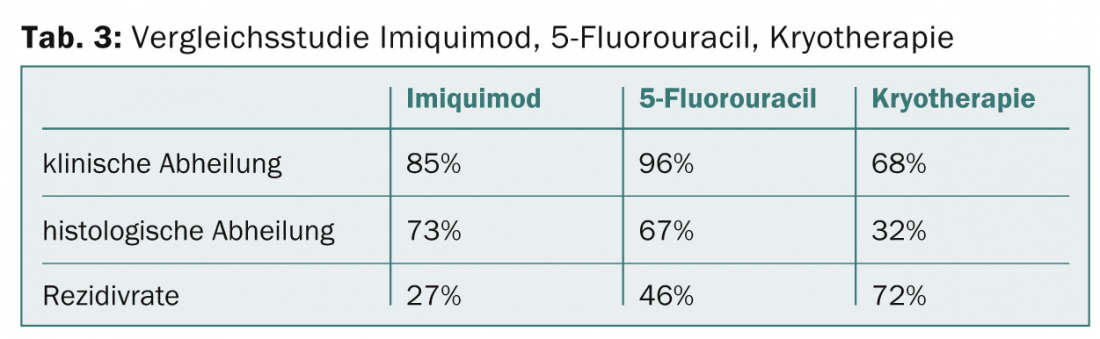

And every few years, new treatment options are added. A comparison of different therapeutic approaches is shown, for example, in table 3. The numerous treatment options might suggest that the ultimate panacea has obviously not yet been found. But it is probably less due to the drug than to the nature of the disease, which, as mentioned at the beginning, is based on permanent DNA damage in the skin. The basic principle of treatment is based on destruction of the affected areas and subsequent re-epithelialization.

Cryotherapy: Cryotherapy with liquid nitrogen (-195°C) represents the most common physically destructive treatment procedure in the treatment of actinic keratoses in everyday life. Frequency, duration, intensity and specific temperature in the treatment area are unfortunately not standardized, which is reflected in the studies as treatment success between 67 and 99% and recurrence rates between 1.2 and 12% within the first year. The method is inexpensive, requires little time and is well tolerated by the patient without local anesthesia. The length of freezing correlates with effectiveness, but also with possible side effects (hypo/hyperpigmentation, scars).

Photodynamic therapy: Photodynamic therapy (PDT) is based on selective destruction of skin tumor cells in the epidermis and dermis using a photosensitizing substance (5-aminolevulinic acid [ALA], methyl-5-amino-4-oxopentanoate [MAL, Metvix®]) and irradiation with high-energy red light. Healing rates range from 70 to 90% and cosmetic results are predominantly rated “excellent” or “good” in the studies. However, the time required (three hours should elapse between application of the cream and irradiation), pain, and stronger local reactions (erythema, edema, pustules, erosions) are perceived as disadvantages.

To simplify the treatment procedure, an ALA-containing patch (Alacare®) has recently become available.

A new variant to conventional PDT is the so-called daylight PDT, which can be performed from the end of April to the end of September. After curettage of crusts and hyperkeratoses and application of sunscreen SPF 20, MAL is applied to the actinic keratoses without occlusion and the patient is instructed to stay outside for 90 to 120 minutes (depending on sun exposure) between 11 am and 4 pm after about half an hour. After that, MAL should be washed off. In a Danish study, healing rates ranged from 50% to 76%, and pain was significantly less or absent with this type of PDT.

Topical 5-fluorouracil (Efudix®): 5-fluorouracil is a pyrimidine analogue that is incorporated into RNA and DNA as an antimetabolite, thus inhibiting the synthesis of this nucleic acid. In addition, inhibition of thymidyl synthetase occurs. 5-Fluorouracil 5% should be applied twice daily for two to four weeks, but other dosage variations are also common, e.g., every other day for three weeks, up to and including self-treatment by the patient. Usually, there are more or less pronounced inflammatory reactions up to erosions, blisters or necroses, which can eventually be therapy-limiting. One study showed up to 96% clinical healing, but this was only 54% after twelve months.

Topical low-dose 0.5% fluorouracil in combination with 10% salicylic acid (Actikerall®), applied once daily, generally shows fewer inflammatory skin reactions. However, complete healings are also seen in only 72-77% in the studies.

Imiquimod (Aldara®): Imiquimod is a specific TLR-7 agonist and causes a release of a number of cytokines (IFN-alpha, IL-1, IL-6, IL-12 and TNF-alpha), leading to an increase in cellular immunity with antiviral and antitumor properties. The cream is applied three times a week for four weeks. In the studies, complete healing rates are found between 54 and 69, partial (>75% reduction) between 61 and 80%. Recurrences after two years were seen in 20% of patients.

Diclofenac in hyaluronic acid gel (Solaraze®): Diclofenac as a COX1 and COX2 inhibitor slows proliferation and neoangiogenesis in carcinogenesis and promotes apoptosis. The gel is applied twice a day for 60-90 days. Response rates were found to be 71-79, but complete healings were found to be only between 17 and 50%. Adverse reactions (pruritus, erythema, hyp- and paraesthesias, photoallergic reactions) are observed significantly less than with imiquimod or 5-fluorouracil.

Ingenol Mebutate (Picato®): The gel, which is derived from a spurge and can only be applied topically to a maximum area of 25 cm2 over three consecutive days, induces a breakdown of the membrane potential of mitochondria with consecutive cell necrosis, which manifests itself clinically in a more or less severe toxic dermatitis. Studies have shown complete clinical cure rates ranging from 40 to 54.4% and partial remissions up to 83%.

Design an individual treatment concept

The overview shows that a variety of treatment options and modalities are available today in the therapy of actinic keratosis. Each method offers certain advantages, but also disadvantages. The goal must therefore be to design an individually adapted treatment concept together with the patient. Not every patient responds to a particular therapy as well as another. Conversely, severe toxic dermatitis may present as a side effect in one patient but not in another. The initial interview has a very important function. As a dermatologist in practice, it is therefore central to be familiar with all treatment options for actinic keratosis.

Conclusion for practice

- Actinic keratoses are a marker of chronic sun damage and carcinogenesis of the skin.

- Early treatment of actinic keratoses is indicated.

- A variety of treatment options for actinic keratoses are available.

- Education and an individual treatment concept are fundamental in the therapy of actinic keratoses.

Uwe Hauswirth, MD

Literature:

- AWMF-Guideline of the German Dermatological Society: Actinic keratosis 2011.

- Kornek T, Augustin M.: Skin cancer prevention. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2013; 11(4): 283-296.

- Cook BA, et al: Is tenderness a reliable predictor for differentiating squamous cell carcinomas from actinic keratoses? J Am Acad Dermatol 2011; 65: 211-212.

- Zalaudek I, et al: Dermatoscopy of facial actinic keratosis, intraepidermal carcinoma and invasive squamous cell carcinoma: A progression model J Am Acad Dermatol 2011 (epub ahead of print).

- Wiegell SR, et al: Daylight-mediated photodynamictherapiy of moderateto thick actnic keratoses oft he face and scalp: a randomized multicentre study. Br J Dermatol 2012; 166: 1327-1332.

- Krawtchenko N, et al: A randomized study of topical 5% imiquimodvs. Topical 5-fluorouracil vs. cryosurgery in immunocompetent patients with actinic keratoses: a comparison of clinical and histological outcomes including 1-year follow-up. Br J Dermatol 2007; 157: 34-40.

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2014; 2(9): 15-18.