According to the WHO, more than 10,000 people have now been infected with Ebola – about half of them died from the virus. The number of unreported cases is far higher. Although the epidemic is predominantly raging in West Africa (and here mainly Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone), in October people in Europe and the USA also fell ill for the first time. How is Switzerland preparing for a possible emergency and what recommendations are being made for doctors?

Of the five known strains of Ebola virus, four are transmissible to humans or are symptomatic with fever, weakness, limb pain, headache, and pharyngitis after an incubation period of 2-21 days. Muscle pain in the back region is also common. This is followed by diarrhea and vomiting. On the fifth to seventh day of illness, a characteristic rash with vesicles is found. It becomes particularly dangerous in the case of coagulation disorders, which can cause bleeding in the gastrointestinal tract, on the gums or subcutaneously, for example. Liver and kidney failure are also possible. Human transmission occurs only in symptomatic patients and exclusively through their bodily excretions such as blood, vomit, feces, urine or saliva, but not through the air. The virus is also transmissible via semen, so men remain infectious for up to seven weeks after recovery. Furthermore, cadavers are a significant source of infection. 50-90% of those infected die from the virus.

How prepared is Switzerland?

Only once, in 1995, has the Ebola virus been introduced into Switzerland. Because the risk of an infected person entering the country is currently considered low, Swiss airports are not conducting increased border controls (there are also no direct flight connections to Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone). The risk assessment coincides with that of the EU. However, the FOPH says it has developed a contingency plan with airports that will be applied if the situation worsens. According to the Federal Council, corresponding measures in hospitals and asylum reception centers are also subject to an ongoing review and optimization process. Some asylum seekers from Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone had previously been identified as potential suspect cases in national reception centers, where infection could not be ruled out. According to the Federal Council, this indicates a functioning control. None of the individuals had actually become infected. Overall, few asylum seekers from the affected regions enter Switzerland.

Infected Swiss aid workers based in Geneva would be assigned to the University Hospital of Geneva – where the reference laboratory is located – as a first step. All laboratory tests to confirm the diagnosis must be discussed with an infectiologist and approved by the cantonal physician in charge. There is no causal therapy yet, one can only fight the symptoms. According to the FOPH, all large Swiss hospitals have appropriate isolation rooms and specially trained staff. Other hospitals also work out emergency concepts in close consultation with each other and with specialists. Various new therapeutic methods and also a vaccination are being researched, but are currently neither approved nor available. At the end of October, Swissmedic gave the green light for a clinical placebo-controlled phase I trial at CHUV: The vaccine cAd3-EBO-Z will be tested on 120 volunteers, some of whom will travel to West Africa. It remains to be seen how effective and safe the drug is. For primary caregivers, the following recommendations continue to apply if Ebola is suspected:

- Ask if the person has been in West Africa (Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone) in the last three weeks.

- If the answer is no, Ebola can be ruled out.

- If the answer is yes, the physician should contact the cantonal physician or a reference physician designated by the canton. The latter assesses the situation and determines the further course of action.

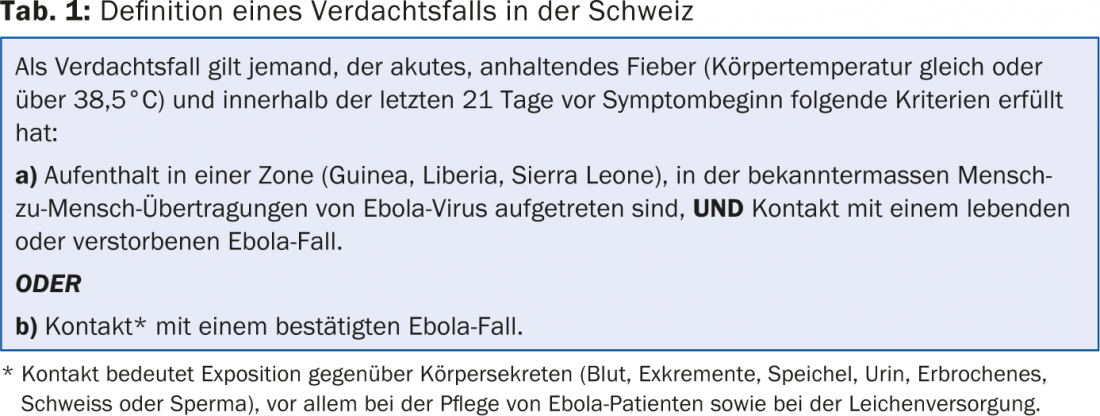

Table 1 summarizes again the official Swiss definition of a suspected Ebola case.

Making better use of existing resources

A recent article published in the New England Journal of Medicine [1] emphasizes that with the best possible supportive therapy, many more lives could be saved than is currently the case. In the absence of specific antiviral therapies or vaccines, some physicians helping in affected regions fall into a kind of therapeutic nihilism or wait for salvation from a specific therapy, according to the authors. It is always assumed that there is a lack of material for a good accompaniment in particular. It is underestimated how much already easily applicable measures such as intravenous catheters, hydration and electrolytic care can make a difference. This leads to negligent underuse of such procedures and disregards the risk of hypovolemic shock. Experimental drugs could only be introduced on the basis of a comprehensive supportive treatment – and this is precisely where there is still a great need for improvement, according to the paper.

Reinfection possible?

A New England Journal of Medicine webcast noted that currently Ebola coordination and decision-making is behind the curve. Although international cooperation is now better structured and organized, there is still room for improvement, according to one expert. In addition to the United States, the WHO and the United Nations have also stepped up their efforts and are on the way to developing a robust concept for dealing with this epidemic that does not violate the dignity of the individual and takes account of the social context.

When asked about the risk of reinfection or recurrence of the disease after recovery, Armand Sprecher, MD, of Médecins Sans Frontières, responded as follows: “We do know that survivors have specific antibodies in their blood, but we don’t know what threshold levels provide reliable protection against Ebola. We hope to gain more knowledge here as vaccine research continues.” To date, it is known that in Monrovia, several treated children under the age of five returned febrile and PCR-positive several weeks later after being PCR negative. Because the children also had neurological symptoms, the experts suspect that although the immune response was able to destroy the viruses in the periphery, the viral infection progressed in the central nervous system and later manifested again as positivity.

Literature:

- Lamontagne F, et al: Doing Today’s Work Superbly Well – Treating Ebola with Current Tools. N Engl J Med 2014; 371: 1565-1566.

For inquiries: Federal Office of Public Health, information on Ebola at +41 (0)58 463 00 00. The Infoline is in operation every day from 8 am to 6 pm

For more information on Ebola: www.bag.admin.ch/de/ebola

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2014; 9(11): 6