In most cases, multiple sclerosis is relapsing-remitting and can progress to a chronic progressive stage over time. Which therapy management is used depends on the individual circumstances as well as the effectiveness, safety and tolerability of the treatment. In the meantime, established active substances have been further developed to improve the quality of life of those affected.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an inflammatory disease of the nervous system. In Switzerland, it is estimated that around 15,000 people are affected. This means that around one in 560. inhabitants suffer from MS. In 80% of sufferers, the first symptoms appear between the ages of 20 and 40. This makes MS the most common neurological disease diagnosed at this stage of life [1]. The exact causes of MS are still unknown. It is assumed that there is a combination of genetic disposition and a considerable influence of environmental factors. Examples of this would be certain viruses as infectious agents, vitamin D deficiency or geographical characteristics.

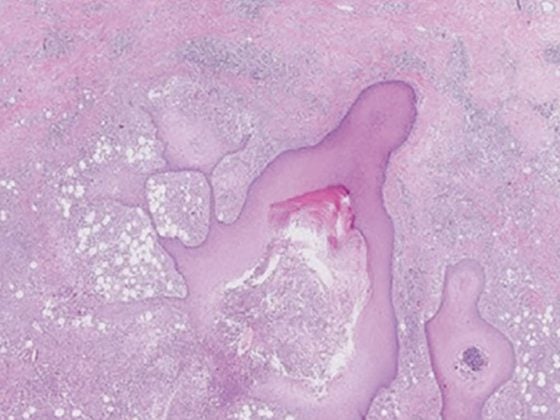

The aim of research is and remains to be able to cure the disease one day. Until then, neurodegeneration, among other things, will be investigated in more detail [2,3]. It is largely responsible for the development of disabilities due to axonal transection and loss of neurons. Increasing neurodegeneration, which most likely starts earlier than previously thought, seems to be a major cause of disease progression. Research into biomarkers, such as the neurofilament light protein, which detects axonal or general neuronal damage and can be used to better assess the prognosis of individual patients, is also moving towards personalized therapy [4,5]. The central role of astrocytes in the processes involved in MS has recently been investigated [6]. A research group from Basel was able to show that the blood level of a cell component called “glial fibrillary acidic protein” (GFAP) increases when astrocytes are activated or increasingly degraded. Elevated GFAP blood levels could therefore be associated with both current and future progression of MS.

Early therapy management

Treatment is individualized and adapted to the needs of the person concerned. The earlier therapy can be initiated, the better. Several effective treatment options are now available that can often greatly slow the progression of the disease. In principle, therapy management is based on the four-pillar model of relapse prophylaxis, acute relapse therapy, symptomatic therapy and rehabilitative therapy. The aim of treatment is to reduce the extent of the inflammatory reactions, stabilize the functional limitations and improve the accompanying symptoms.

During an acute MS attack, high doses of cortisone are usually used to reduce inflammation. If the symptoms do not improve sufficiently, the cortisone treatment is repeated at a higher dose. If this is also unsuccessful, plasma separation is performed [7]. Beta-interferons or glatiramer acetate are used to prevent relapses in mild and moderate forms of the disease. Since 2013/14, the substances teriflunomide and dimethyl fumarate (DMF) have also been approved as a treatment option for MS patients with relapsing-remitting MS. Both substances have predominantly anti-inflammatory properties, but have different effects. DMF has now been further developed into diroxime fumarate. Both active substances are prodrugs that are converted in vivo to the active metabolite monomethyl fumarate. Exactly how this metabolite works in MS has not yet been detected in detail. It is assumed that monomethyl fumarate enhances the effect of the Nrf2 protein. The resulting increased production of antioxidants appears to help control the activity of the immune system and reduce damage to the brain and spinal cord in MS [8]. The further development scores particularly well in terms of its gastrointestinal tolerability profile.

In patients with a (highly) active course (i.e., many, severe relapse events in a short period of time and/or (highly) active MRI) or patients who do not respond adequately to basic immunotherapeutics, escalation therapy medications are used. These include, for example, infusion therapies with the monoclonal antibody Natalizumab. Fingolimod is also approved as an escalation therapy. Alemtuzumab or oral short-term therapies such as cladribine tablets can also be used to treat relapsing forms of MS. Rarely and only as an alternative, immunosuppressants such as those used in cancer (e.g. mitoxantrone or cyclophosphamide) can also be considered [7].

Literature:

- www.multiplesklerose.ch/de/ueber-ms/multiple-sklerose (last accessed on 24.01.2024)

- Ziemssen T, Derfuss T, de Stefano N, et al: Optimizing treatment success in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol 2016; 263: 1053-1065.

- De Stefano N, Airas L, Grigoriadis N, et al: Clinical relevance of brain volume measures in multiple sclerosis. CNS Drugs 2014; 28: 147-156.

- Barro C, Benkert P, Disanto G, et al: Serum neurofilament as a predictor of disease worsening and brain and spinal cord atrophy in multiple sclerosis. Brain 2018; 141(8): 2382-2391.

- Benkert P, Meier S, Schaedelin S, et al: Serum neurofilament light chain for individual prognostication of disease activity in people with multiple sclerosis: a retrospective modeling and validation study. Lancet Neurology 2022; 21(3): 246-257.

- Meier S, Willemse EAJ, Schaedelin S, et al: Serum Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein Compared With Neurofilament Light Chain as a Biomarker for Disease Progression in Multiple Sclerosis. JAMA Neurology 2023; 80(3): 287-297.

- www.neurologen-und-psychiater-im-netz.org/neurologie/erkrankungen/multiple-sklerose-ms/therapie (last accessed on 24.01.2024)

- www.pharmazeutische-zeitung.de/fumarat-der-naechsten-generation-130969 (last accessed on 24.01.2024).

InFo NEUROLOGIE & PSYCHIATRIE 2024; 22(1): 24