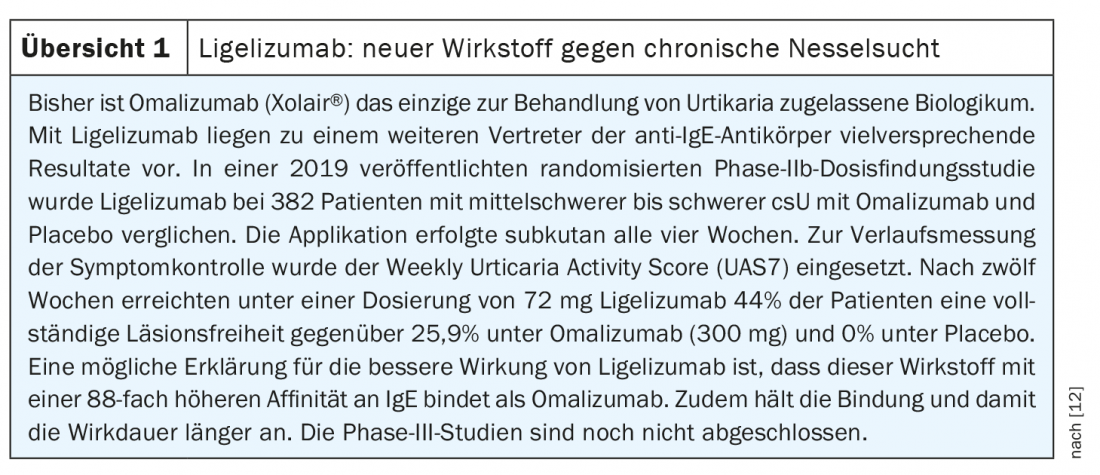

The therapeutic goal of complete freedom from symptoms is realistic in many cases thanks to the treatment options available today. H1 antihistamines are still considered first-line therapy, and the use of omalizumab is recommended if there is a lack of response. Another IgE antibody is currently in the pipeline, and the study data to date are extremely promising. Standardized instruments such as the Urticaria Activity Score (UAS7) and the Urticaria Control Test (UCT) are helpful for measuring progression.

Chronic urticaria is defined as the presence of itchy wheals and/or angioedema for longer than six weeks. It is a common and, for many patients, highly distressing condition. Daily performance can be significantly impaired and chronic urticaria is often accompanied by depression, anxiety disorders and sleep disturbances. Prof. Dr. Marcus Maurer, Dermatologic Allergology, Allergy Center of Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin gave an update on the management of urticaria on the occasion of this year’s DDG Annual Meeting [1]. The new S3 guideline has recently been approved and is scheduled for publication in 2021; the current EAACI/GA²LEN/EDF/WAO guideline is currently authoritative for treatment recommendations (Fig. 1) .

While in chronic inducible urticaria the symptoms can be explained by reproducible specific triggers, such as cold or pressure, in chronic spontaneous urticaria (csU) the pathophysiological cascade is triggered by an intrinsic factor. Autoimmunity is now considered a common cause of chronic spontaneous urticaria. While in csU due to type I autoimmunity IgE autoantibodies bind to the high-affinity receptor of skin mast cells, in type IIb autoimmune CSU IgG autoantibodies against the high-affinity IgE receptor lead to mast cell degranulation [2].

Differential diagnostics based on structured anamnesis

The goals of diagnostic workup in patients with suspected csU include, in addition to differential diagnosis, testing for trigger factors relevant to csU (e.g., use of pain medications), clarification of comorbidities, determination of disease activity and disease control, and assessment of quality of life [3]. When diagnosing chronic spontaneous urticaria, one should think broadly, the speaker emphasized. “It’s not just about the causes, it’s also about identifying and treating comorbidities and consequences in patients.” Following the anamnesis, a physical examination and a basic laboratory diagnosis should be performed (erythrocyte sedimentation rate and/or CRP as well as differential blood count) [3,4]. Extended diagnostics are only indicated in a few cases and should always be performed in parallel with therapy.

For history taking and basic diagnostics, targeted history questions are formulated in the EAACI/GA²LEN/EDF/WAO guideline [3,4]:

- Family history: A positive family history regarding wheals and angioedema may indicate congenital conditions such as autoinflammatory syndromes and hereditary angioedema (HAE).

- Time of onset: on set in early childhood may be indicative of congenital conditions such as cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome (CAPS) or HAE.

- Occurrence of angioedema without the presence of wheals: If angioedema occurs in isolation, consider bradykinin-mediated angioedema (e.g., HAE- or ACE inhibitor/sartan-induced angioedema).

- Duration and localization of angioedema: HAE or other bradykinin-mediated angioedema is possible if angioedema persists for several days, localizes to the larynx or abdomen, or fails to respond to glucocorticoid therapy.

- Duration and sequelae of wheals: Long-lasting wheals (usually >24 h) or subsequent hematoma or hyperpigmentation may indicate urticarial vasculitis.

- Medications: If taking ACE inhibitors or sartans, clarify ACE inhibitor/ sartan-mediated angioedema.

- Associated symptoms: bone/joint pain, inflammatory signs, or fever may be indicative of autoinfammatory syndromes.

- Dependence of the occurrence of wheals and/or angioedema on specific triggers: The exclusive occurrence of wheals and/or angioedema as a result of specific triggers (e.g., skin contact with cold) makes chronic-inducible urticaria likely.

- History of treatment and previous response to therapy (including dosage and duration): Therapy resistance may indicate autoinfammatory syndrome or bradykinin-mediated angioedema disease.

- Previous diagnostic procedures/results: Can correlations be elicited?

- Intermittent occurrence of urticaria and/or accompanying symptoms, such as gastrointestinal complaints: This may indicate IgE-mediated food allergy.

Up-dose antihistamines – anti-IgE antibodies as second-line therapy.

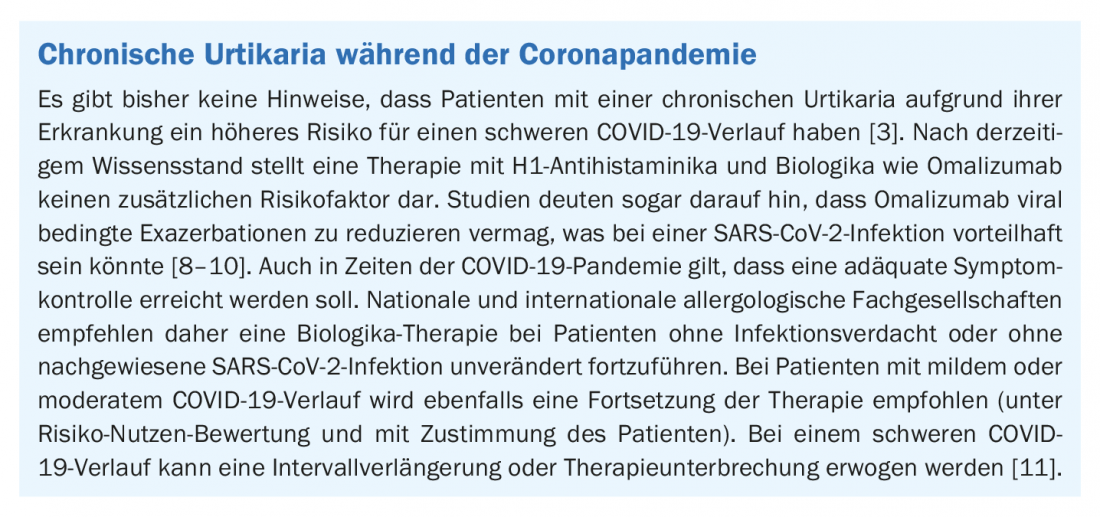

The overall therapeutic goal in csU is to achieve complete freedom from symptoms and thus also to achieve relief of the accompanying symptoms (e.g. depression, anxiety, sleep disorders) [2]. Therapy consists of avoidance of trigger factors and adequate drug treatment (Fig. 1) . The first-line therapy of csU is second-generation H1 antihistamines. (e.g., loratadine or cetirizine) [3]. In case of lack of efficacy, up-dosing of the standard dose is recommended; if possible risk factors or co-medication are taken into account, this is not problematic. If there is no sufficient improvement after two to four weeks with a second-generation H1 antihistamine in standard dosage or after higher dosage, additional treatment with omalizumab (Xolair®) should be given. This monoclonal antibody has a good safety profile and the anaphylaxis rate is low. The use of omalizumab is also safe for mild colds, coughs or hoarseness. Both dead and live vaccines are possible during omalizumab therapy. Without a history of anaphylaxis, patients may self-inject or have a caregiver inject omalizumab after the fourth use (pregnant women excluded). If treatment is not successful after six months of omalizumab, off-label use with ciclosporin A is recommended in addition to existing therapy with H1 antihistamines. In acute exacerbations, short-term (max. 10 days) therapy with medium-high-dose oral systemic glucocorticoids to reduce disease duration and activity. The use of the antihistamine loratadine and cetirizine as well as omalizumab may also be possible during pregnancy.

Progress measurement is extremely important

“Measure your patients’ urticaria,” appeals Prof. Maurer. On the one hand, this allows a fact-based therapy decision and, on the other hand, an adjustment of the treatment during the course, if necessary. The weeklyurticaria activity score (UAS7) [5] and angioedema activity score (AAS ) [6] are used to monitor disease activity. In addition, the urticaria control test (UCT) should be performed in all CSU patients. In UAS7, patients document daily wheals and itching by the patient in a diary for seven consecutive days [5]. Similarly, the occurrence of angioedema is detected by AAS [6]. The UCT is used to record disease and therapy control, which is assessed using four questions (0-4 points per response) regarding the last four weeks. A total score ≤11 points indicates uncontrolled disease [7]. In addition, a regular assessment of the quality of life (e.g. DLQI* or CU-Q2oL** or AE-QoL#) is useful.

* DLQI = Dermatology Life Quality Index

** CU-Q2oL= Chronic Urticaria Quality of Life Questionnaire

# AE-QoL=Angioedema Quality of Life Questionnaire

Congress: DDG Conference 2021

Literature:

- Maurer M: Chronic Urticaria – Practicalities and News on Management, Prof. Dr. Marcus Maurer, S17: Track Allergology: Immediate Type Allergy, Urticaria and Specific Immunotherapy, DDG Conference 2021, 16.04.2021.

- Maurer M, et al: Chronic urticaria – What does the new guideline bring? JDDG 2018; 16(5): 585-595.

- Bauer A, et al: Expert consensus on practice-relevant aspects in the treatment of chronic urticaria. Allergo J Int 2021; 30: 64-75.

- Zuberbier T, et al: EAACI/GA²LEN/EDF/WAO guideline for the defnition, classification, diagnosis and management of urticaria – consented German language translation. Allergo Journal 2018; 27: 41-69.

- Hawro T, et al: The urticaria activity score-validity, reliability, and responsiveness. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2018; 6: 1185-90.e1

- Weller K, et al: Development, validation, and initial results of the Angioedema Activity Score. Allergy 2013; 68: 1185-1192.

- Weller K, et al: Development and validation of the Urticaria Control Test: a patient-reported outcome instrument for assessing urticaria control. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2014; 133: 1365-1372, 72.e1-6.

- Teach SJ, et al: Preseasonal treatment with either omalizumab or an inhaled corticosteroid boost to prevent fall asthma exacerbations. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2015; 136: 1476-1485.

- Esquivel A, et al: Efects of omalizumab on rhinovirus infections, illnesses, and exacerbations of asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2017; 196: 985-992.

- Lommatzsch M, Stoll P, Virchow JC: COVID-19 in a patient with severe asthma treated with omalizumab. Allergy 2020; 75: 2705-2708.

- Klimek L, et al: Use of biologicals in allergic and type-2 infammatory diseases during the current COVID-19 pandemic. Allergo J 2020; 29: 14-27.

- Maurer M, et al: Ligelizumab for chronic spontaneous urticaria. New England Journal of Medicine Oct 2019. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1900408

- Sussman G, et al: Insights and advances in chronic urticaria: a Canadian perspective. All Asth Clin Immun 2015; 11(7), https://doi.org/10.1186/s13223-015-0072-2

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2021; 31(3): 30-31 (published 6/1/21, ahead of print).