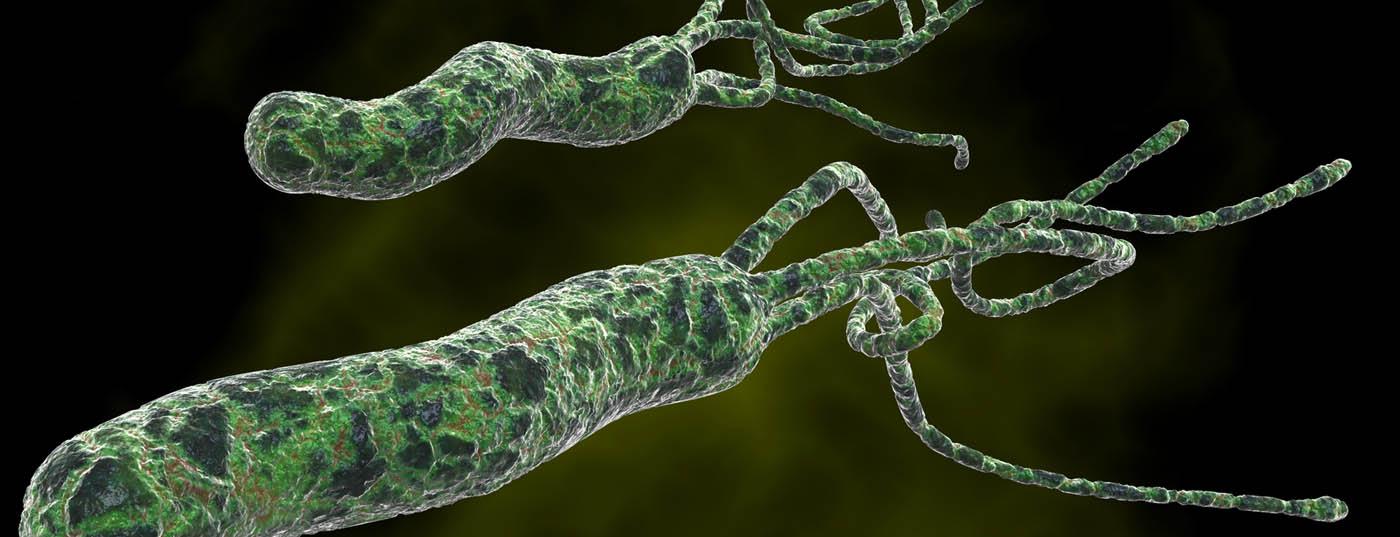

At ASCO-GI in San Francisco, David Graham, MD, of Baylor College of Medicine, gave a presentation on the relationship between Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer, emphasizing the importance of preventive eradication programs. In addition, he described in detail how bacteria are related to pathogenesis and provided an overview of the most important developments in recent years in this regard.

According to David Graham, MD, Houston, Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is so critical in gastric cancer because it is an inflammation-associated cancer in which inflammation is caused by chronic infection of the stomach with this pathogenic bacterial species. Inflammation induced by H. pylori causes progressive and cumulative damage to the gastric mucosa, which is reflected clinically in the exponential increase in the incidence of gastric cancer (usually after the age of 50). Over 95% of such cancers are due to H. pylori inflammation.

“This infection is a necessary but not sufficient cause in gastric cancer. Major advances in the understanding of gastric physiology, histopathology, and microbiology led to the first link between gastric cancer and atrophic gastritis in the late 19th century [1],” Graham elaborated. “It was thus clear to subsequent researchers that they had to search for the cause of gastritis in order to theoretically prevent gastric cancer [2]. After the many advances in this field were first summarized in their entirety in 1951 [3], a long dry spell of 35 years followed before it was established with certainty that H. pylori was one of the most important causes of gastritis. Nearly another thirty years had to pass, however, before Japan finally became the first country to admit a comprehensive gastric cancer prevention program using H. pylori eradication in February 2013, consisting of a test-and-treat approach [4].”

Genetic instability

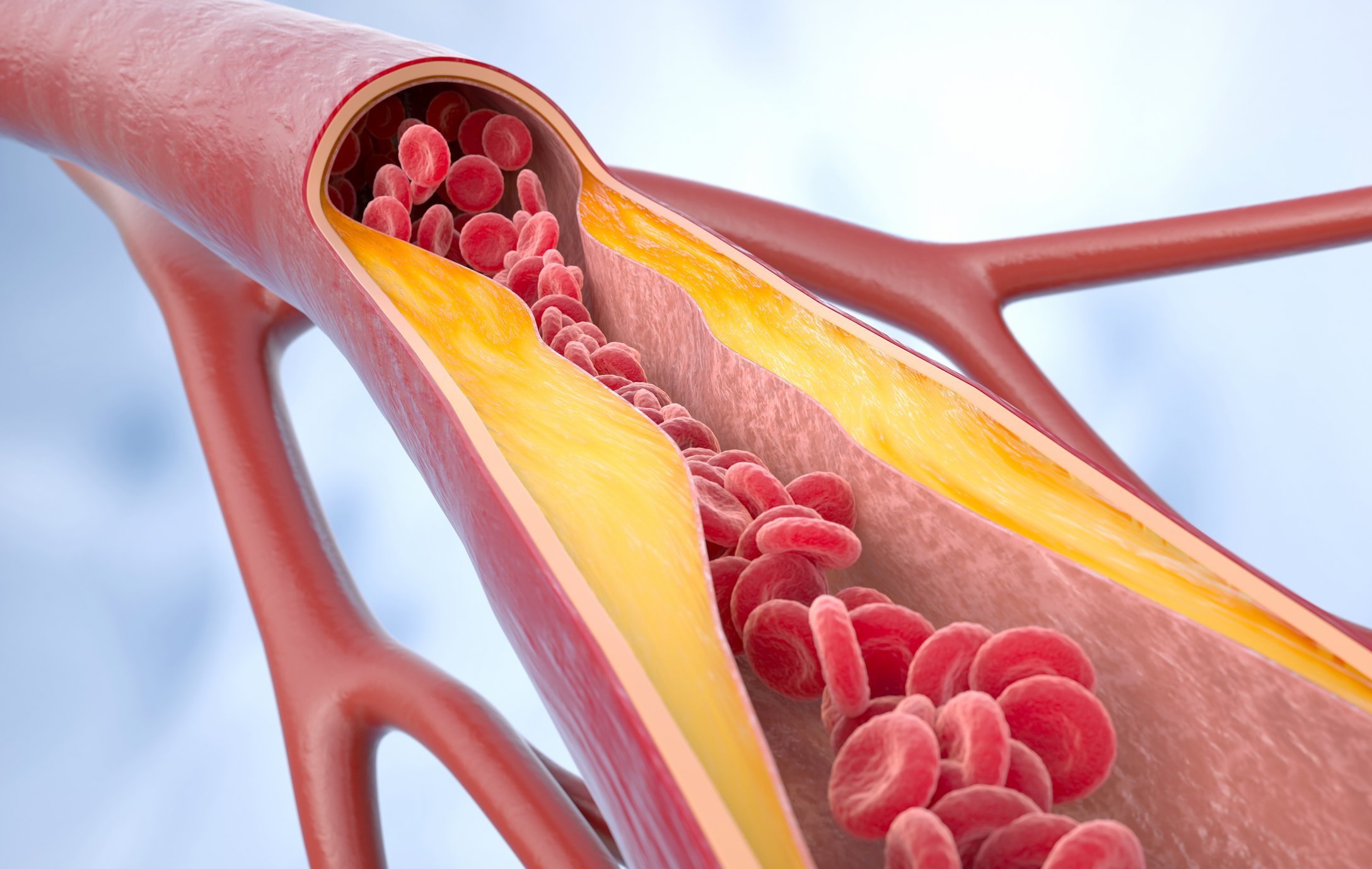

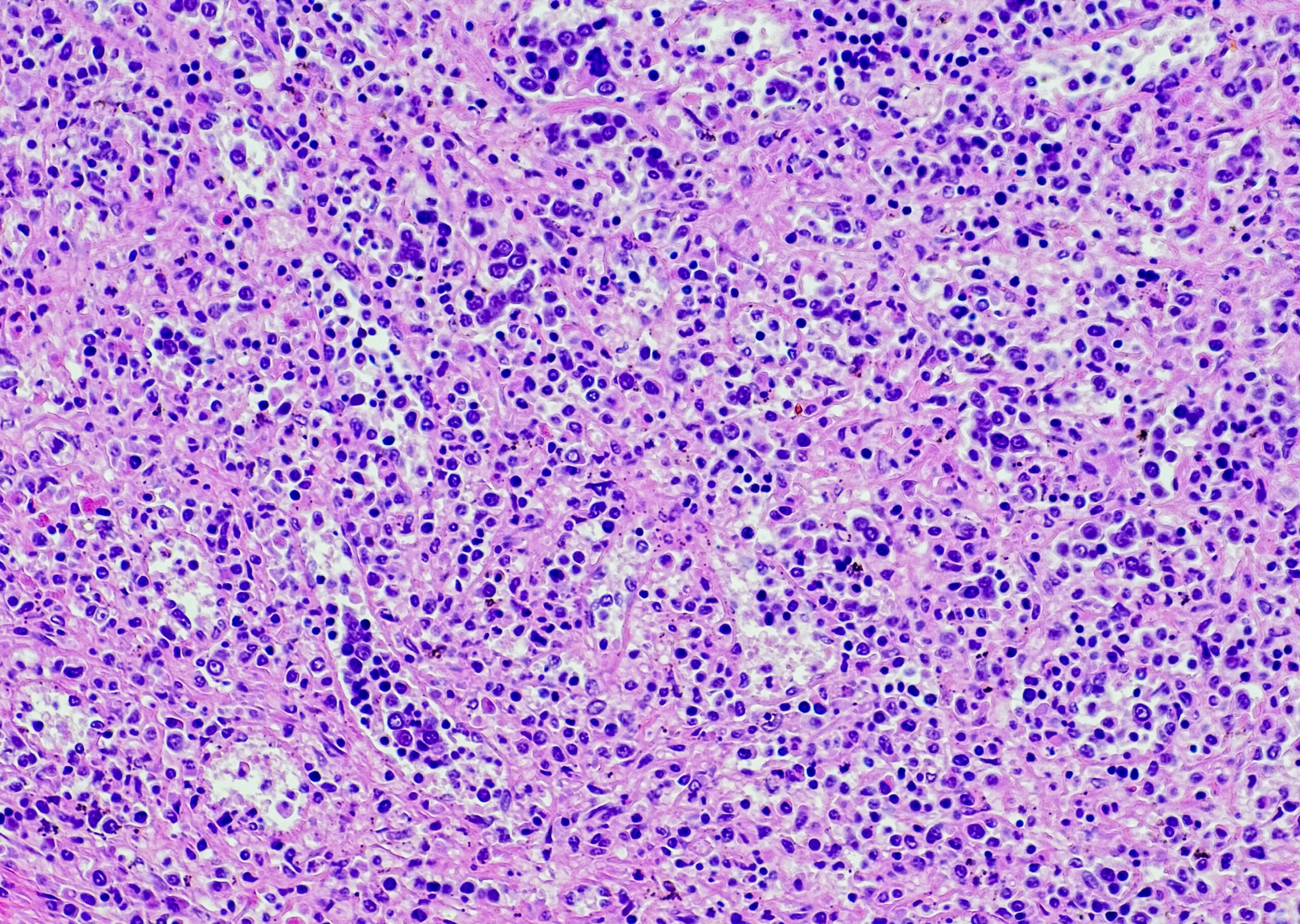

In addition to inflammation, contact of H. pylori with gastric epithelial cells can directly lead to genetic instability [5]. In most cases, a combination of both effects is responsible for the cancer. The instabilities associated with H. pylori occur in all H. pylori infections, including those without a large increase in risk for gastric cancer (such as nonatrophic gastritis or duodenal ulcer). Thus, normally, cell repair mechanisms seem to respond adequately to such H. pylori-induced damage.

Since gastric cancer is associated with a loss of normal gastric epithelial cells, it would be interesting to compare the repair mechanisms of different types of gastric epithelia, according to Graham: “Evidence that the genetic damage associated with H. pylori plays a role in carcinogenesis comes from a study of 544 patients who were at high risk for developing metachronous cancers. Here, a 3-year follow-up showed that eradication was more effective in preventing the interaction between H. pylori and gastric cells and thus progression to carcinoma in 272 patients (9 vs. 24 in control group) [6].”

Eradication as safe prevention?

Eradication can address the most fundamental cause of stomach cancer, according to Graham. Nevertheless, the effects of such a program will not be immediately apparent, since high-risk countries continue to have many people in whom gastritis has progressed to the point where the risk for gastric cancer remains high despite eradication. Although eradication stops the progression of both cancer risk and damage, some risks remain; after all, some damage is irreversible, according to Graham. The progression also varies in different individuals. It is influenced by the strength of the host’s inflammatory response, which in turn is related to genetic, environmental, and dietary factors.

Risk after eradication

“What is the risk after H. pylori eradication?” asked Graham the question. “Of course, this has to do with the extent and severity of atrophic gastritis at the time of eradication: For example, if it is a nonatrophic gastritis, the risk is small; if it is an atrophic pangastritis, it is high [1].”

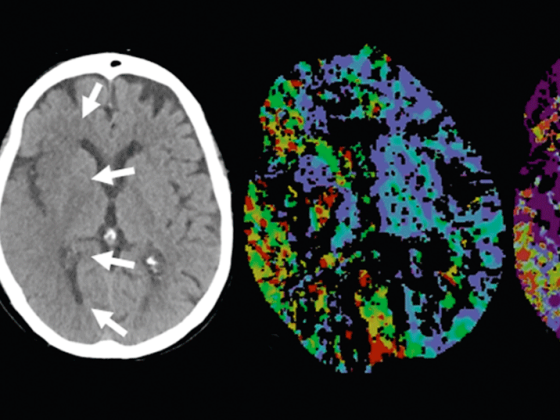

Therefore, in high incidence regions, it is recommended that risk stratification be performed along with eradication to identify those patients who would potentially benefit from cancer surveillance after eradication. As mentioned above, this stratification is based on the extent and severity of atrophic gastritis (noninvasively by changes in serum pepsinogen/gastrin levels, or by gastric mucosal biopsy indicating atrophy) [7, 8]. The approach combines primary (H. pylori eradication) and secondary prevention (endoscopic surveillance), according to Graham, thereby identifying those patients for whom it is cost-effective to continue monitoring. This form of stratification has replaced age-based.

“In most cases, only a few percent of those treated are in the surveillance group [1],” Graham said. “In conclusion, H. pylori is an important human pathogen whose potential beneficial effects have been shown to be futile and which should be eradicated. It remains to be seen how often and for how long surveillance should take place, and what specific risk-reduction strategies should be considered: H. pylori eradication for all? Diet (fresh fruits and vegetables)? Smoking cessation? Medication (anti-inflammatory, gastroprotective)? In any case, there is an urgent need to think about such questions.”

Source: Gastric Cancer – Etiology, Development, and Implication for Therapy, General Session 2 at ASCO GI – Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium, January 16-18, 2014, San Francisco

Literature:

- Graham DY, Asaka M: Eradication of gastric cancer and more efficient gastric cancer surveillance in Japan: two peas in a pod. J Gastroenterol 2010; 45: 1-8.

- Massarrat S. Konjetzny: A German surgeon of the past century and his pioneering hypothesis of a bacterial aetiology for gastritis, peptic ulcer and gastric cancer. Z Gastroenterol 2005; 43: 411-413.

- Comfort MW: Gastric acidity before and after development of gastric cancer: its etiologic, diagnostic and prognostic significance. Ann Intern Med. 1951; 36: 1331-1348.

- Asaka M: A new approach for elimination of gastric cancer deaths in Japan. Int J Cancer 2013; 132: 1272-1276.

- Shiotani A, Cen P, Graham DY: Eradication of gastric cancer is now both possible and practical. Semin Cancer Biol. 2013 (in press).

- Fukase K, et al: Effect of eradication of Helicobacter pylori on incidence of metachronous gastric carcinoma after endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer: an open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2008; 372: 392-397.

- Rugge M, et al: Gastritis staging in clinical practice: the OLGA staging system. Gut 2007; 56: 631-636.

- Dinis-Ribeiro M, et al: Validity of serum pepsinogen I/II ratio for the diagnosis of gastric epithelial dysplasia and intestinal metaplasia during the follow-up of patients at risk for intestinal-type gastric adenocarcinoma. Neoplasia 2004; 6: 449-456.

InFo Oncology & Hematology 2014; 2(3): 38-39.