Since its quantum leap in 2014, hepatitis C therapy has been in a constant state of flux. Prof. Dr. med. Dr. h.c. Darius Moradpour, Lausanne, took the audience at the SGAIM Congress on a journey through the most important stages of diagnosis and treatment of this common infectious disease. Much has happened, much remains to be done. Awareness among the general population in particular is still low, in contrast to HIV, where major information campaigns have made decisive progress.

“Worldwide, there are approximately 80-180 million people with chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection,” said Prof. Dr. med. Darius Moradpour of the CHUV in Lausanne by way of introduction. In Switzerland, the number is estimated to be about 80,000 people, or 1% of the population. Over half of them are unaware of their infection. Moreover, since it is usually asymptomatic for many years, the peak of late complications or disease burden is not expected until 2030. In terms of mortality, HCV has long since overtaken HIV. “So the myth, widespread in the general population, that viral hepatitis is a rare disease that people don’t normally come into contact with can be dispelled. In fact, chronic viral hepatitis B and C are among the most common infectious diseases in the world. One in twelve people is affected,” warned Prof. Moradpour. The consequences are serious: in 50-80%, acute hepatitis C progresses to a chronic form. After approximately 30 years, cirrhosis of the liver is imminent in 15-30% of cases, which in turn may progress to hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in 1-6% of patients per year. Where do all these cases come from?

In addition to clinical signs or symptoms of hepatitis, the following risk factors are the main reasons for testing for chronic HCV infection.

Infection:

- Medical (especially recipients of blood transfusions or solid organs before 1992, but also persons with HBV or HIV infection or on hemodialysis).

- demographic (e.g. country of origin Egypt or already southern Italy)

- Occupation or behavior (e.g., occupational contact with infected persons; intravenous or intranasal drug use; men who have sex with men; frequently changing sexual partners)

- other factors such as long prison sentences, piercing or tattoos, children of HCV-infected mothers.

Three-quarters of all HCV infections affect persons born between 1945 and 1965 in the United States, representing a prevalence in this group of 3.5%. With the realization that it is the so-called “baby boomer” generation that is most frequently infected, screening efforts are increasing [1] (in Switzerland, it is mainly those born between 1951 and 1985 who are affected).

Staging and new drugs

For staging liver fibrosis, the METAVIR score is commonly used in Switzerland (liver biopsy). Also increasingly used is the so-called fibroscan. This is a practical, non-invasive procedure that allows a statement to be made about liver stiffness: the higher the kPa value recorded, the harder the liver. Consequently, the measurement shows a correlation with fibrosis. It is recognized in the reimbursement of new hepatitis C medications. “Much has been written about the latter in the professional and lay press,” noted Prof. Moradpour. “Sometimes the scope of medical success is somewhat forgotten in light of the cost and limitatio discussion (which is certainly justified). It is important to realize what an incredible advance these direct-acting antiviral (DAA) drugs represent for hepatitis C therapy. We now achieve cure rates (‘sustained virological responses’ [SVR]) 12 or 24 weeks after treatment of over 90%.”

In terms of a single example among many, the speaker showed the results from the ASTRAL studies with sofosbuvir and velpatasvir: in all groups (HCV genotypes 1-6), SVR12 scratched the 100% mark or even reached it [2,3]. While viral suppression is the goal with HBV or HIV (i.e., years to lifelong therapy is necessary), viral elimination and thus a cure is in prospect with HCV. After SVR, reactivation of the virus is no longer possible, but the risk of reinfection remains.

Rapid development

For a long time, (pegylated) interferon-α and ribavirin were considered the standard of care, achieving cure rates of nearly 50% for genotype 1 infections and 70-80% for genotype 2/3, with considerable potential for side effects. The major breakthrough came in 2014 with the new oral interferon-free DAA combinations, which provide highly effective therapy for all genotypes, combined with shorter treatment duration and good tolerability. These, in turn, were preceded by the establishment of a replication system of the virus in 1999 – a decisive step on the way to the development of the new substances.

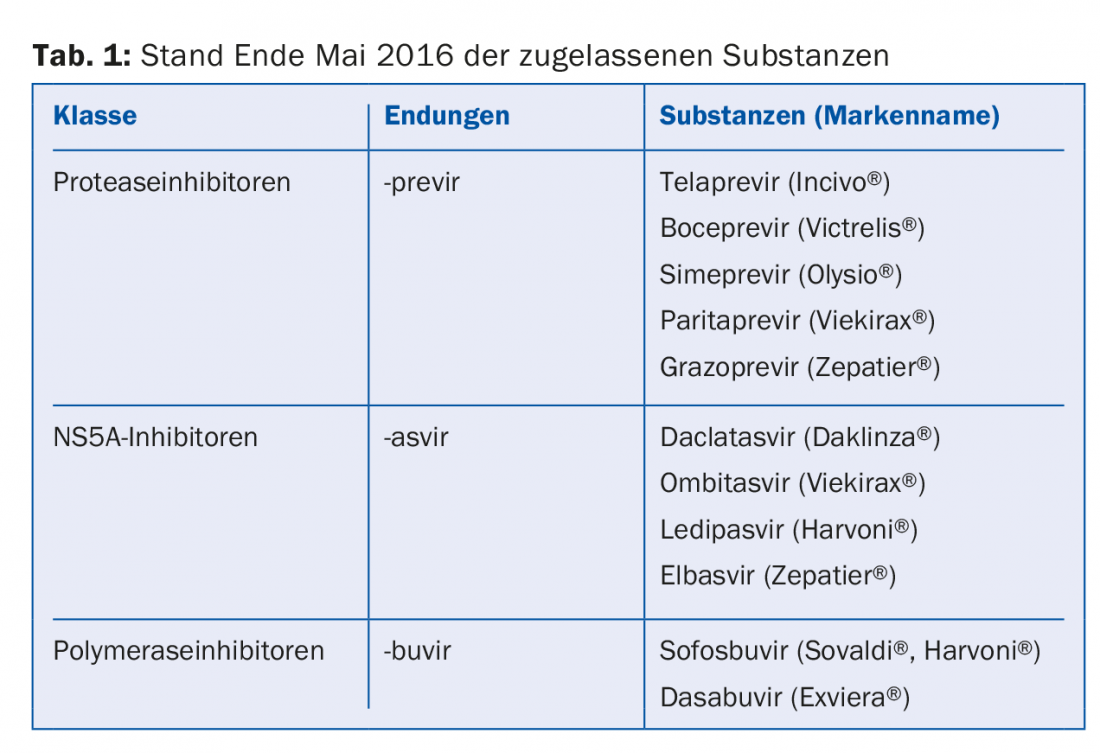

“So we have achieved a lot. And it’s continuing at a rapid pace. Therapy recommendations are constantly changing. For general practitioners, it is probably almost impossible to keep track of everything, and even for us specialists it is sometimes difficult. So I can only give you the current state of affairs as of the end of May 2016,” the speaker emphasized. The substances approved at this time are shown in Table 1. They can be divided into protease inhibitors (with the suffix -previr), NS5A inhibitors (-asvir) and polymerase inhibitors (-buvir).

Unresolved issues

Although the new hepatitis C drugs would actually have the potential to eliminate the epidemic, this goal is still a long way off (also in Switzerland). Not only is pricing a problem, but screening and awareness in the general population need to be improved. The hepatitis C treatment revolution will not by itself lead to improved care. On the contrary, due to limitations in reimbursement and testing and clearance rates that still need improvement, treatment numbers continue to lag far behind disease numbers.

“It is self-explanatory that the problem is drastically exacerbated for poorer countries. Even wealthy Switzerland can hardly afford such an aggressive pricing policy. Better access to prevention, diagnosis and treatment must therefore be created as a matter of priority for the more than 80% less privileged in the world,” the expert concludes. Also, one should not lose sight of the resistance problem in patients who do not respond to the new drugs (e.g., due to suboptimal therapy regimens, etc.). “Viruses are smart; you should never underestimate their adaptability,” Prof. Moradpour concluded.

Source: SGAIM Congress, May 25-27, 2016, Basel

Literature:

- Smith BD, et al: Recommendations for the identification of chronic hepatitis C virus infection among persons born during 1945-1965. MMWR Recomm Rep 2012 Aug 17; 61(RR-4): 1-32.

- Feld JJ, et al: Sofosbuvir and velpatasvir for HCV genotypes 1, 2, 4, 5, and 6 infection. N Engl J Med 2015 Dec 31; 373(27): 2599-2607.

- Foster GR, et al: Sofosbuvir and velpatasvir for HCV genotype 2 and 3 infection. N Engl J Med 2015 Dec 31; 373(27): 2608-2617.

GP PRACTICE 2016, 11(7): 37-38