Errors in diagnosis not only lead to an increase in mortality rates, but also to numerous legal cases. And they are often preventable. Current research shows: For all higher-level interventions to improve diagnostic accuracy, domain-specific knowledge remains central.

The diagnostic process is a central element of medical practice – and it is extremely complex. There are far-reaching decisions to be made in uncertain situations. In addition to the temporal dynamics of disease, the risk of over- and underdiagnosis must also be considered. All of these challenges contribute to 10-15% of diagnoses being incorrect [1]. Laura Zwaan, assistant professor at the Institute of Medical Education Research in Rotterdam (NL), has been studying the complexity of clinical decisions for years, specializing in particular in the cognitive causes of diagnostic errors.

A trip to the casino

In principle, three types of decision-making exist. The simplest among them is considered to be decision making with known consequences of all options, such as the choice of drinks after entering a casino. With this one, you always know what you’re getting. Furthermore, there are decisions which are made under a certain risk, but the probabilities of different consequences are known. Thus, at the roulette table, one decides on a color or a number – and knows the respective chances for one’s luck as well as the corresponding consequences of the selection made. Finally, the most complex decisions are those where the probabilities of the possible outcomes are unknown. If the person sitting next to you suddenly collapses, there could be various causes behind it and, accordingly, a wide variety of decisions could be appropriate. The key here is to minimize the uncertainty around decision making by capturing as much information as possible. Is it a heart attack or is the collapsed man just trying to avoid paying his debts?

Dealing with uncertainty

Physicians are confronted with the most complex type of decision-making every time a diagnosis is made. This is not only about making the right decision, but also about how we deal with uncertainty. Too many diagnostic tests, like too little diagnostics, can lead to poorer outcomes. This is also due to the false sense of security that is often conveyed. For example, novice clinicians are on average less tolerant of uncertainty than more experienced clinicians and initiate more diagnostic workups-which can have unpleasant consequences for patients and place a burden on the health care system [2]. A certain tolerance for uncertainty is essential for successful management, according to Zwaan. However, a tolerant approach is often difficult, not least because of the expectations of patients, relatives, superiors and the system itself. One should not neglect the factor of time and the natural course of the disease, the expert said. This is often decisive for the correct diagnosis. After ruling out a dangerous acute situation, it was therefore entirely justified to wait – without a final diagnosis.

Poor marks for self-assessment

In addition to hasty decisions, a dangerous pitfall in the diagnostic process seems to be self-assessment. How does physician safety correlate with diagnostic accuracy? Or: Do we know that we do not know? Unfortunately, the answer to this question is far too often: No. In this context, better assessment of our uncertainty could improve management in the long term, including by requesting second opinions and closer monitoring. In scientific terms, the so-called “accuracy-confidence correlation” needs improvement. This is particularly important in cases that are difficult to diagnose. To this end, Zwaan’s presentation included a study in which only 5% of participants correctly identified the disease they were looking for – with 65% of physicians convinced they had made the correct diagnosis [3]. Compared with simpler case vignettes, diagnostic correctness decreased significantly with increasing difficulty, but physician confidence decreased minimally. This source of error could be effectively counteracted by establishing a feedback culture. After all, how are we supposed to train our self-assessment if we never even find out if our diagnosis was correct?

Thinking process in focus

Being more aware of the thought process during a diagnostic decision can also contribute to safety, according to Zwaan. However, it has been shown over the years that any form of “debiasing” – improving diagnostic accuracy by raising awareness of various sources of error – usually remains without relevant success. Classic measures of such efforts include slowing down the decision-making process and consciously questioning the diagnosis. The underlying problem with such interventions is primarily the timing of their application. While in retrospect, when the correct diagnosis is established, it is almost always possible to identify a source of error in the thought process, classical debiasing measures at the time of diagnosis with limited available information are of very limited help.

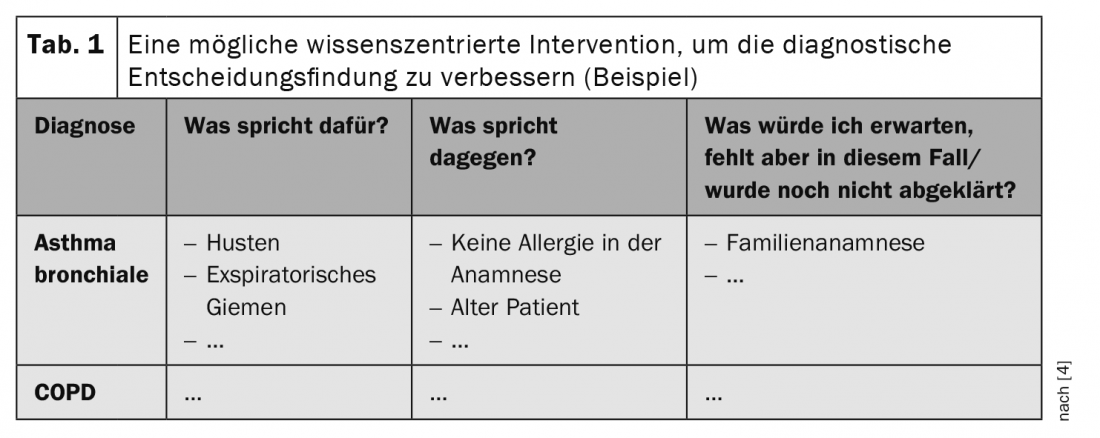

But how should we then counter availability heuristics and the like? (Small note: Availability heuristic refers to the bias of a decision in favor of what is “stuck” in our brains for whatever reason – i.e., what is currently available. For example, if you listened to a podcast on the subject of corona on your way to work, it is more likely that you will first think of COVID-19 when you see the patient with shortness of breath and cough, and not of the heart failure that is actually present). Well, current research concludes that successful interventions must be one thing above all: content-centered. Solid expertise seems to be the most effective way to prevent bad decisions – though certainly not the easiest. For example, evaluation of the most likely diagnoses using an adapted pros and cons list leads to a significant reduction in diagnostic errors (Table 1) [4]. Impressive and clear results in this direction were also provided by a recently published study that compared the theoretical knowledge of physicians with the clinical outcome of their patients [5]. Comparison of the 30% best in the theoretical test with the 30% worst showed a 2.9-fold reduction in deaths and a 4.1-fold reduction in hospitalizations. So there is no way around specialist knowledge in quality assurance either. Zwaan pleads for a more content-specific approach, which could be started already in education. Thus, instead of analyzing one example in great detail, she suggests introducing many representations of the same clinical picture into the lesson without too much detail. After all, we recognize Roger Federer even in the most atypical pictures without knowing every detail about him – and that’s simply because we’ve seen him so often from all angles.

Also, according to the expert, the importance of pre-test probability in diagnostics needs to be given more importance in many places. This is because, in addition to having the most well-founded specialist knowledge and adequate self-assessment, the correct interpretation of test results is also crucial for a successful diagnostic process. Considering prevalence, symptoms, and risk factors in the evaluation of a diagnostic result can prevent serious errors and uncertainty. The same test has different meanings in different populations, and it is important to take this into account.

Construction manual for the correct diagnosis

Step-by-step instructions for correct diagnosis do not exist, but with increasing findings from research and the ever-growing role of quality management in medicine, it is clear that expertise is at the heart of a successful diagnostic process. So instead of following generalized checklists and over-analyzing your own thought process, the old principle of “practice makes perfect” applies much more. Furthermore, there is a clear need for action in the area of physician self-assessment, which could be improved by establishing a feedback culture. Here, the many interfaces pose a challenge, which is magnified by the often not quite low-threshold communication culture and the time pressure. Nevertheless, monitoring patient trajectories is worthwhile – for individual development and safety across the healthcare system.

Zwaan sees great potential for artificial intelligence in the area of diagnostic safety. Since computers make different mistakes than humans, a collaboration is quite promising, he said. Unfortunately, there is currently still a lack of understanding of how best to incorporate artificial intelligence, but it could bring great advances to her field in the future, she said. In addition to individual decision making, he said, there is still much room for improvement at other levels that would contribute to greater diagnostic certainty. For example, he said, a lot still needs to happen in the areas of communication and organization to provide the optimal framework for individual action [6].

Source: Keynote Lecture “Uncertainty and Error in Medicine: How to Improve Diagnostic Quality and Safety”, Prof. Laura Zwaan, April 21, 2021, SGAIM Spring Congress 2021.

Literature:

- Berner ES, Graber ML: Overconfidence as a cause of diagnostic error in medicine. Am J Med 2008; 121(5 Suppl): S2-23.

- Lawton R, et al: Are more experienced clinicians better able to tolerate uncertainty and manage risks? A vignette study of doctors in three NHS emergency departments in England. BMJ Qual Saf 2019; 28(5): 382-328.

- Meyer AN, et al: Physicians’ diagnostic accuracy, confidence, and resource requests: a vignette study. JAMA Intern Med. 2013; 173(21): 1952-1958.

- Mamede S, et al: Immunising physicians against availability bias in diagnostic reasoning: a randomised controlled experiment. BMJ Qual Saf 2020; 29(7): 550-559.

- Gray BM, et al: Association between primary care physician diagnostic knowledge and death, hospitalisation and emergency department visits following an outpatient visit at risk for diagnostic error: a retrospective cohort study using medicare claims. BMJ Open 2021; 11(4): e041817.

- Zwaan L, et al: Advancing Diagnostic Safety Research: Results of a Systematic Research Priority Setting Exercise. J Gen Intern Med 2021. DOI: 10.1007/s11606-020-06428-3. Epub ahead of print.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2022; 20(1): 38-39.