The leading symptoms of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) are chronic diarrhea (>4 weeks), abdominal pain, bloody stools, and rapid weight loss. IBD is often relapsing, with active phases alternating with inactive phases, and in other cases there is a chronic-active course. Crohn’s disease (MC) and ulcerative colitis (CU) are the main subtypes of IBD – they are systemic diseases associated with extraintestinal manifestations and comorbidities in addition to intestinal complications.

This training article is based on the training series “IBDmatters”, eLearning module 2, “Extraintestinal manifestations and comorbidities” [1,2]. Module 1 dealt with state-of-the-art pharmacotherapy, and the corresponding article appeared in HAUSARZT PRAXIS 1/2021 [1].

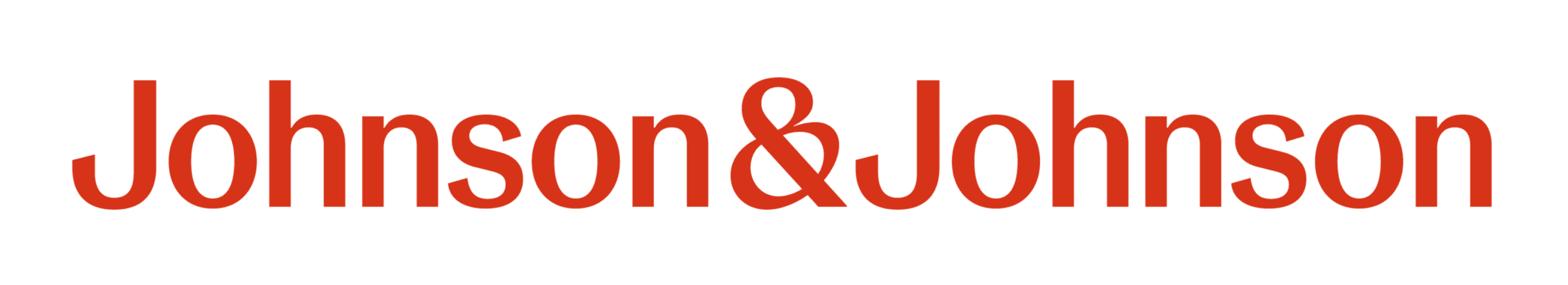

The leading symptoms of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) are chronic diarrhea (>4 weeks), abdominal pain, bloody stools, and rapid weight loss. IBD is often relapsing, with active phases alternating with inactive phases, and in other cases there is a chronic-active course. Crohn’s disease (MC) and ulcerative colitis (CU) are the main subtypes of IBD – they are systemic diseases associated with extraintestinal manifestations and comorbidities in addition to intestinal complications. The manifestations outside the gastrointestinal tract can have a massive additional impact on the quality of life of patients with IBD. Multidisciplinary collaboration is essential for effective treatment. The treatment spectrum available today ranges from conventional drugs to state-of-the-art biologics and JAK inhibitors. By definition, EIM involves inflammatory processes outside the gastrointestinal tract. In distinction to actual EIM, extraintestinal complications are consequences of inflammatory processes. Examples include osteoporosis, kidney stones, gallstones, peripheral neuropathies. Comorbidities associated with IBD include psoriasis, vitiligo, type 1 diabetes mellitus, or autoimmune thyroid disease.

EIM: Inflammatory processes outside the gastrointestinal tract

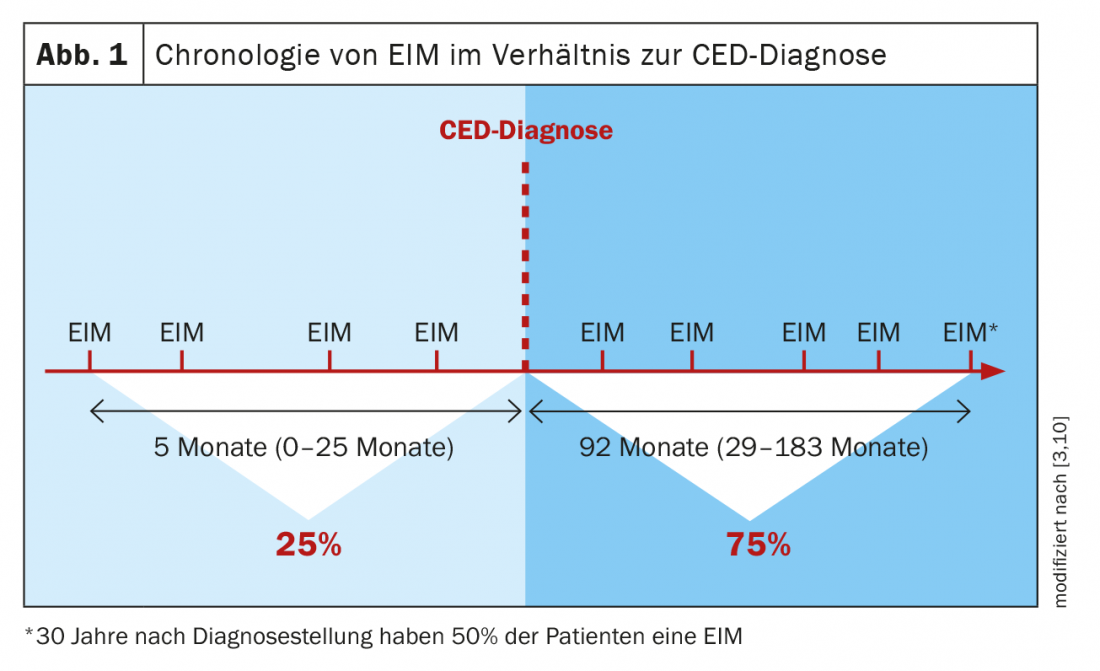

The prevalence of extraintestinal manifestations (EIM) is reported in the literature to range from 6% to 47% [3]. Classic EIM include rheumatic symptoms, ocular symptoms, cutaneous manifestations, and hepatobiliary symptoms. In 25% of IBD patients, extraintestinal manifestations may occur before diagnosis, while in the majority of patients they develop during the course of the underlying disease (Fig. 1) [3,4]. The presence of an extraintestinal manifestation increases the risk of further EIM [3]. The classic forms of extraintestinal manifestations are [5]:

- Joints and bones: spondyloarthritis, arthritis

- Eyes: uveitis , episcleritis, scleritis

- Skin: erythema nodosum, pyoderma gangraenosum

- Liver: primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), autoimmune hepatitis, primary biliary cholangitis

Rheumatologic EIM: According to data from the Swiss IBD Cohort Study, arthritis is the most common extraintestinal manifestation. In Crohn’s disease (MC), the incidence was one-third of study participants, and in ulcerative colitis (CU), it was approximately one-fifth [6]. In type 1 (“pauciarticular”), mainly large joints are affected, less than 5. Classically, the knee, ankle or wrist are affected, sometimes also the elbow or hip. It is important to note that these symptoms usually occur in parallel with intestinal disease activity and are often self-limiting with resolution within 10 weeks. Another characteristic of type 1 arthritis is that other EIM are often present, such as erythema nodosum and uveitis. In contrast, type 2 symptoms are independent of IBD disease activity and may persist for months or even years. Affected are mainly small joints, from the number 5 or more. Affected are mainly small joints of the hands or fingers (symmetrical or asymmetrical). However, in clinical practice, one also frequently sees CED patients with a mixed form of arthritis type 1 and type 2 as rheumatoid EIM.

Ocular EIM: The typical ocular symptoms are uveitis, scleritis or episcleritis. Symptoms of uveitis may include eye pain, redness of the eyes, mouches volantes, loss of vision, or a combination of these. Scleritis is a severe, destructive inflammation of the sclera that can also threaten vision. Episcleritis is inflammation of the tissue between the sclera and conjunctiva, symptoms include redness, swelling and irritation of the eye. The incidence of ocular EIM is reported to be 2-29%. Symptoms may manifest unilaterally or bilaterally.

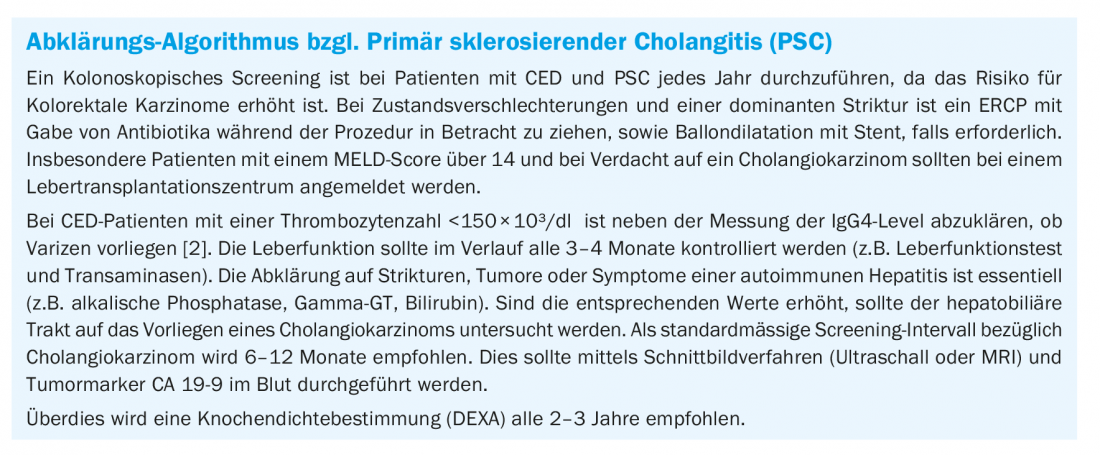

Hepatobiliary EIM: In particular, autoimmune liver diseases (PSC, autoimmune hepatitis, primary biliary cholangitis) are subsumed under hepatobiliary EIM. Furthermore, steatosis or cholelithiasis may occur as complications of IBD [5]. Also to be considered are abnormal liver function values associated with IBD medication. The most important hepatobiliary EIM is primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) [7,8]. In CU, the prevalence averages about 5%, and in MC, about 3-4%. Men are more frequently affected than women. 90% of PSC patients suffer from IBD. MRI (MRCP) is used as a standard diagnostic procedure, sometimes ERCP. Measurement of alkaline phosphatases can also be informative. In a Swedish cohort study, 85% of CU patients with elevated serum alkaline phosphatases showed PSC [7]. Pruritus and lethargy are common associated symptoms, with approximately 40-50% of patients with PSC being asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis (mean age: 40-50 years). PSC is a major risk factor for cholangiocarcinoma and colorectal cancer. Dominant strictures (CAVE!) may be indicative of cholangiocarcinoma.

Cutaneous EIM: Pyoderma gangraenosum and erythema nodosum are the most common cutaneous EIM. Pyoderma gangraenosum is a neutrophilic, chronic progressive skin necrosis of unknown etiology that often occurs in the setting of systemic disease. Initially, there is usually an inflamed erythematous papule, pustule or nodule. The lesion eventually ulcerates and rapidly expands to form a swollen necrotic base with raised dusky red to livid margins. The ulcers are usually sterile, and no bacterial superinfections form. The ulcerative subtype is the most common. Among patients in the Swiss IBD Cohort, the extremities were most commonly involved. However, other localizations such as the trunk or face may also be affected. A special form of pyoderma gangraenosum is pyostomatitis vegetans, this manifests inguinal-axillary and oral. Occurrence is independent of IBD disease activity, prevalence is reported to be 1-12%, tending to be more common in CU. Erythema nodosum is associated with pressure-dolent red, soft nodules or plaques, especially in the pretibial region. The skin manifestations may be preceded by fever, malaise, and joint pain, and sometimes these accompanying symptoms are present simultaneously. Erythema nodosum occurs in parallel with IBD activity [3].

At what stage of IBD do EIM occur and what are the risk factors?

There is a broad spectrum of genes involved in IBD, with over 50% of IBD-associated gene loci associated with other autoimmune diseases [9]. Regarding pathomechanisms of extraintestinal manifestations (EIM), there are mainly the following two hypotheses: 1) Extension of immune responses from the intestinal tract, for example, cross-reactivity triggered by microbial antigens, 2) Independent inflammatory processes due to a proinflammatory state. 25% of EIM occur on average 5 months (range: 0-25) months before CED diagnosis, 75% thereafter [3,10] (Fig. 1) . The clinical implication of this is that patients with appropriate extraintestinal symptoms should be screened for IBD. Also known is that the prevalence of EIM positively correlates with disease activity of IBD.

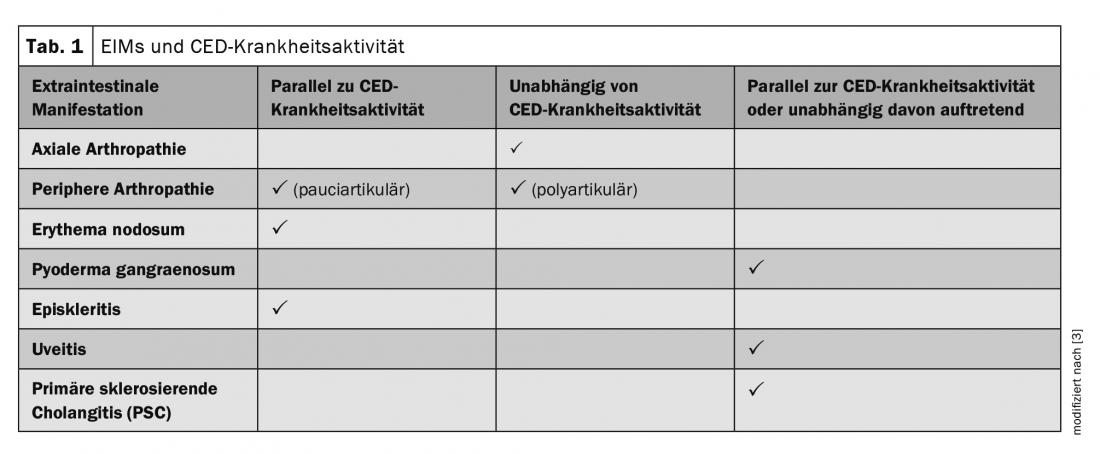

One of the most important risk factors for the occurrence of EIM is the presence of active IBD. In the Swiss Cohort Study, the incidence of arthritis among MC patients was 45% in those with active IBD versus 31% in those with inactive disease (p=0.016). Differences regarding uveitis (12% vs. 5%, p=0.024) were also found to be significant [6]. Which EIM tend to occur in parallel with active IBD or rather independently of it can be seen in Table 1 [3]. In addition to active IBD being the greatest risk factor (OR 1.95, 95% CI: 1.17-3.23, p=0.01) for EIM, a positive family history regarding IBD (OR 1.77, 95% CI: 1.07-2.92, p=0.025) also increases the likelihood of extraintestinal manifestations. Furthermore, a trend concerning EIM and MC with involvement of the upper gastrointestinal tract (perianal area) was shown. No association was shown regarding smoking and EIM [6].

Multidisciplinary treatment strategy for successful disease management

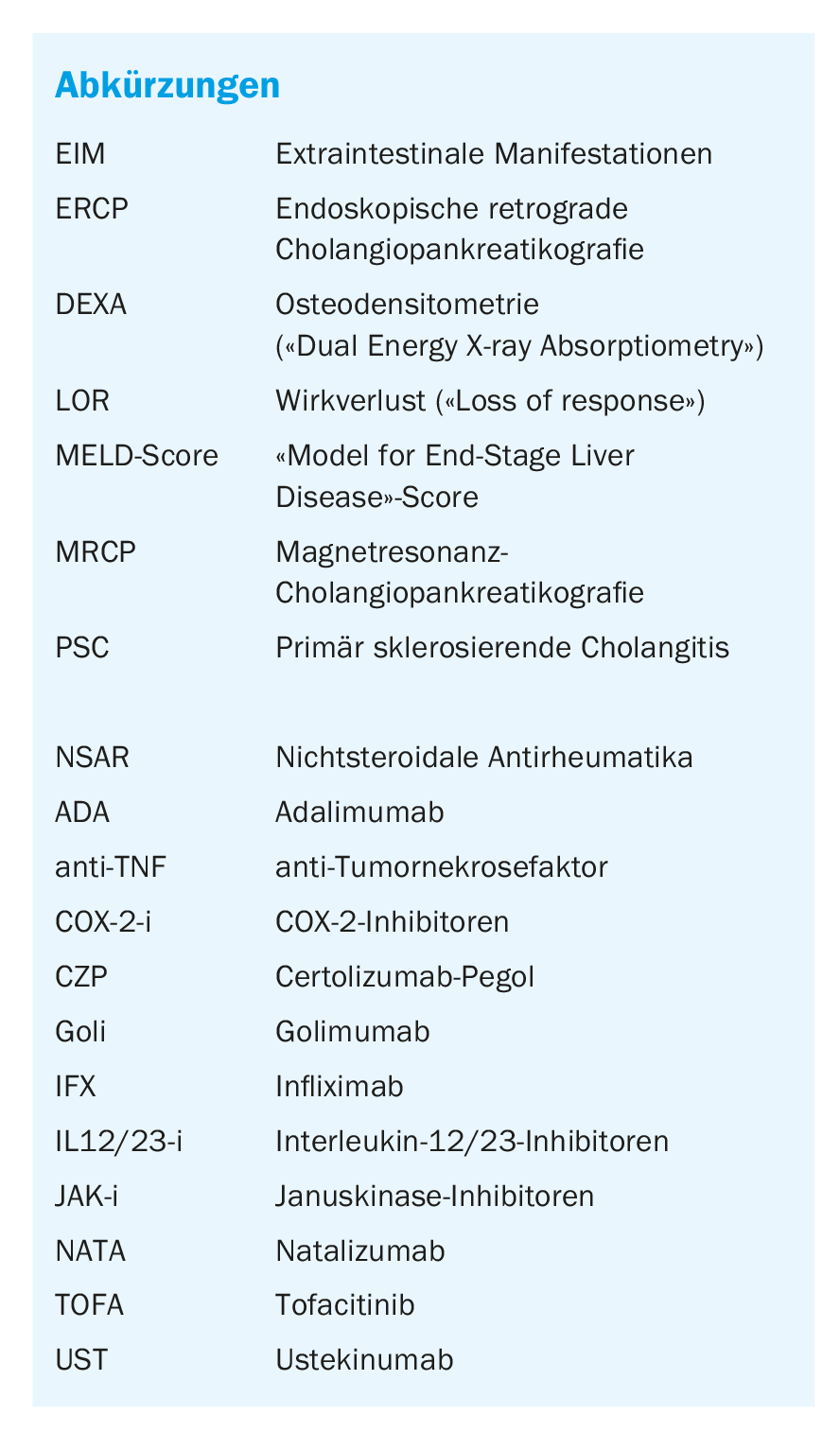

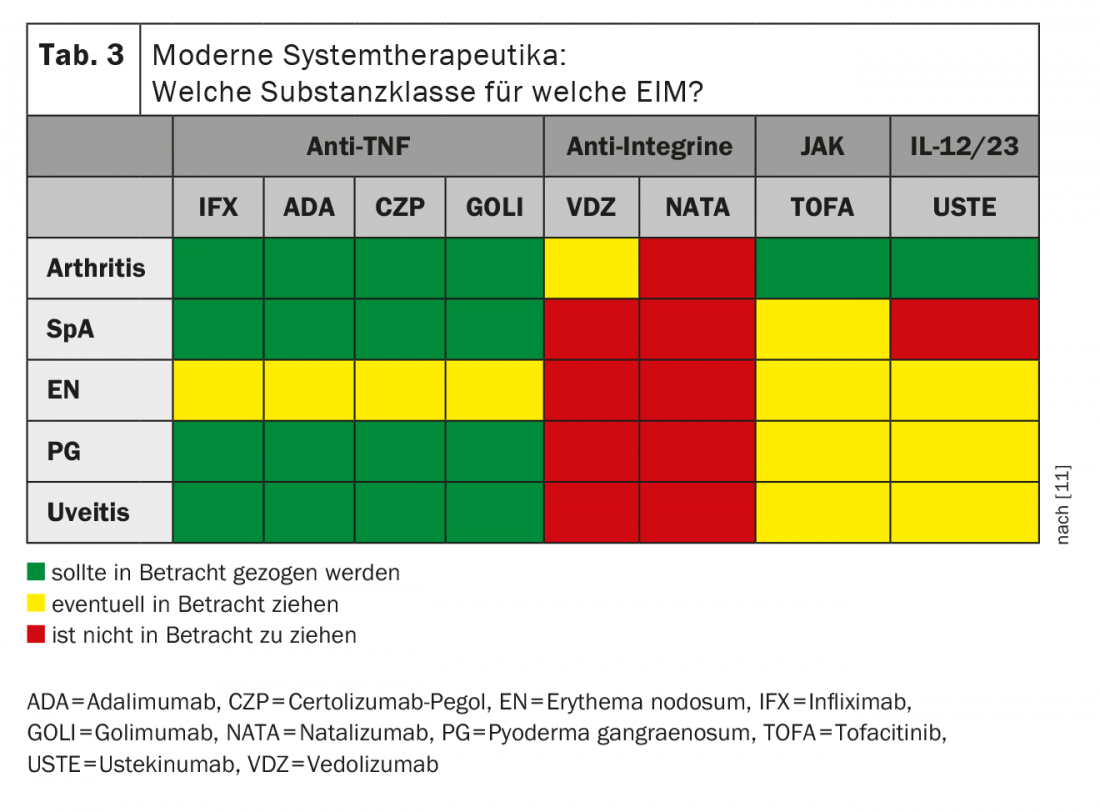

IBD is a relapsing and destructive disease that leads to irreversible damage to the intestinal mucosa over time, depending on its extent and severity. Accordingly, the main goals of treatment for IBD are clinical remission, steroid freedom, improvement of quality of life, mucosal healing, and prevention of extraintestinal manifestations and long-term complications. In this sense, the treatment aims at the most complete healing of the inflammatory changes in the gastrointestinal tract. For the treatment of IBD patients with extraintestinal symptoms, multidisciplinary cooperation of different disciplines is indispensable. For the selection of the appropriate treatment method, a basic rule is: even though there are many possible therapeutic options, the intestinal disease activity must be treated first. The different treatment options are shown in Table 2 [11]. According to current data, there is different evidence of efficacy for different EIM and recommendations for different modern systemic therapeutics based on this evidence (Tab. 3) . An analysis of tissue samples showed that in cutaneous EIM (erythema nodosum, pyoderma gangraenosum) TNF involvement plays a role, so that anti-TNF is a good treatment option in these cases [12].

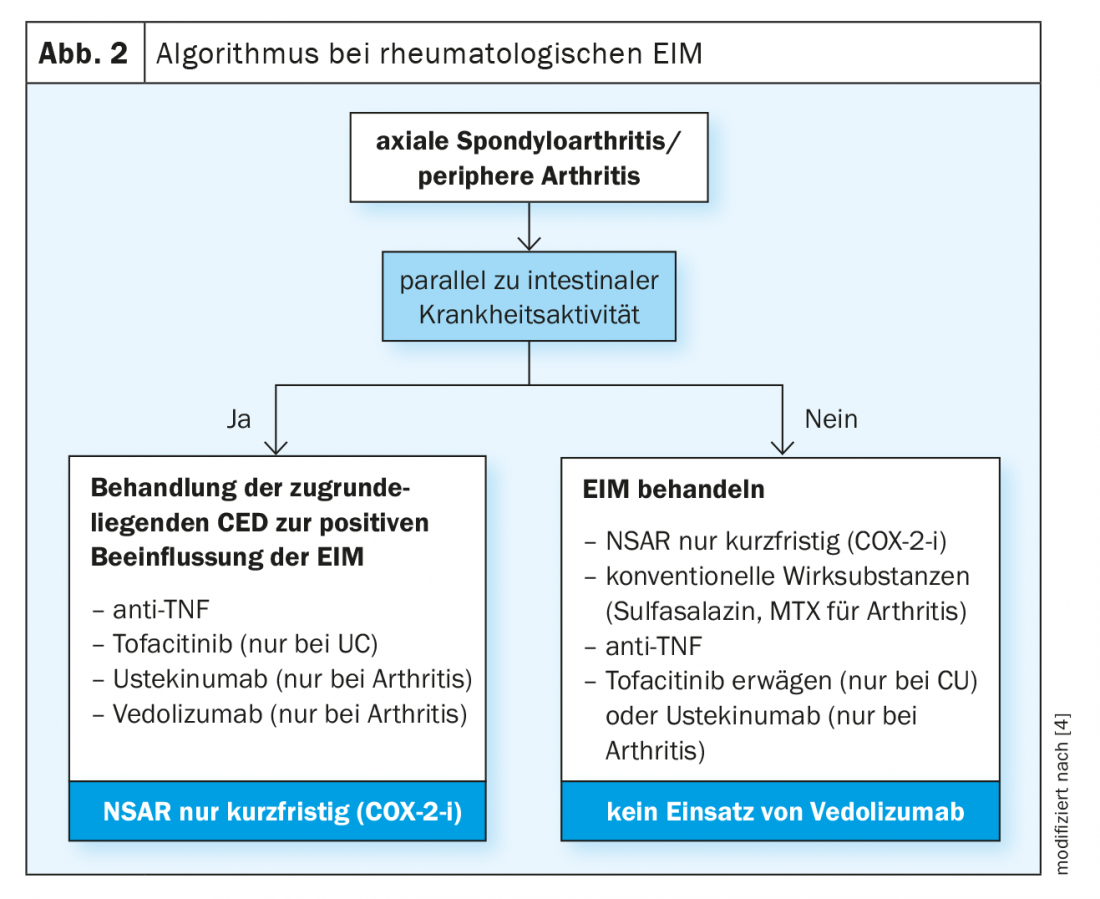

At the time of diagnosis and during the course of inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatologic symptoms should always be inquired about. If such are present, it is first necessary to clarify whether or not they are complaints occurring in parallel with intestinal disease activity. If so, the underlying IBD should be treated in such a way that the EIM is influenced as positively as possible [11] (Fig. 2) . For this purpose, anti-TNF can be used, in case of CU alternatively also tofactinib and if arthritis manifests as EIM ustekinumab or vedolizumab. NSAIDs should only be used for short periods of time. If the rheumatologic EIM do not occur in parallel with intestinal disease activity, anti-TNF can be used in addition to conventional agents (sulfasalazine or alternatively MTX in arthritis) or short-term NSAR, and tofacitinib in CU, if appropriate. Ustekinumab may be considered as an EIM for arthritis. Interdisciplinary collaboration with a rheumatologist is highly recommended in CED patients with joint involvement.

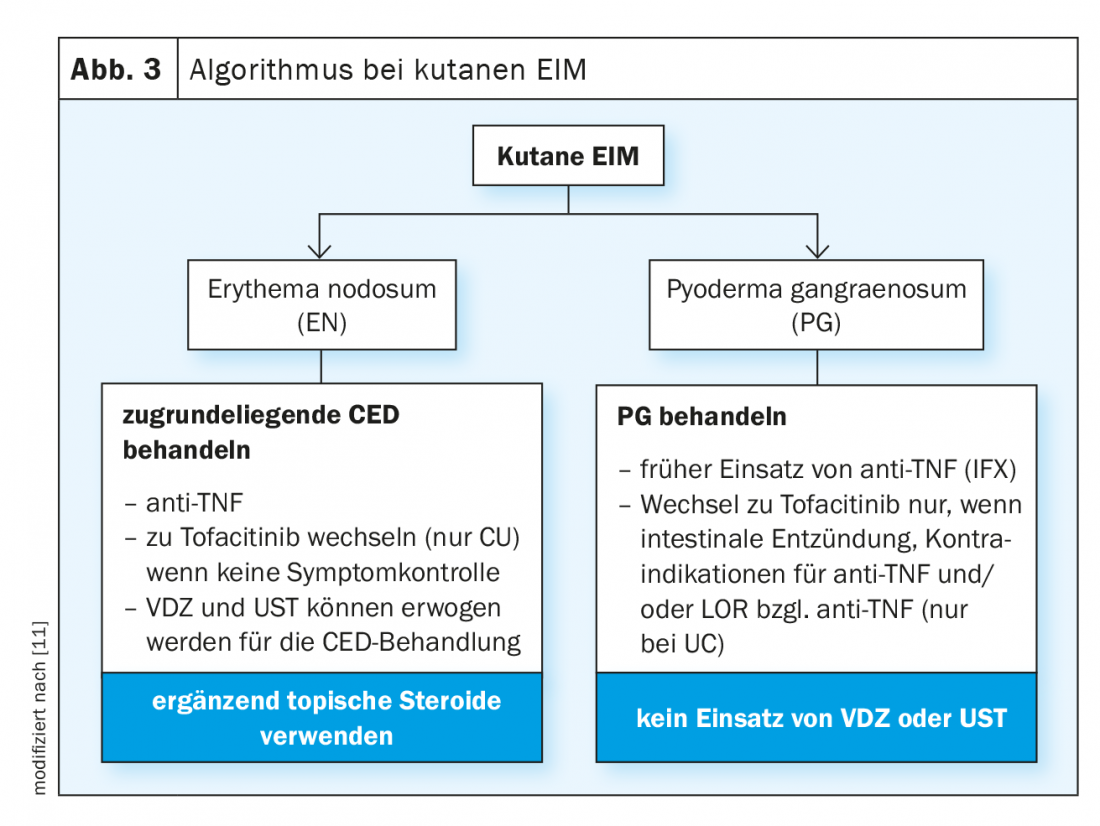

In case of cutaneous symptoms as EIM, collaboration with a dermatologist is advisable. However, in erytherma nodosum, treatment of the underlying IBD may also lead to improvement of cutaneous symptoms. For this purpose, the use of anti-TNF is suitable, or if this is not effective, it is possible to switch to tofacitinib (CU only) [11] (Fig. 3) . If appropriate, vedolizumab and ustekinumab should be considered. Complementary topical steroids should be used to treat skin symptoms. Early use of anti-TNF (infliximab) may be considered for pyoderma gangraenosum. A switch to tofacitinib is only advisable in the presence of intestinal inflammation or contraindications to anti-TNF and/or if UC develops a loss of effect during treatment with anti-TNF. Caution is advised regarding the use of vedolizumab and ustekinumab in IBD patients with pyoderma gangraenosum, as insufficient data are available.

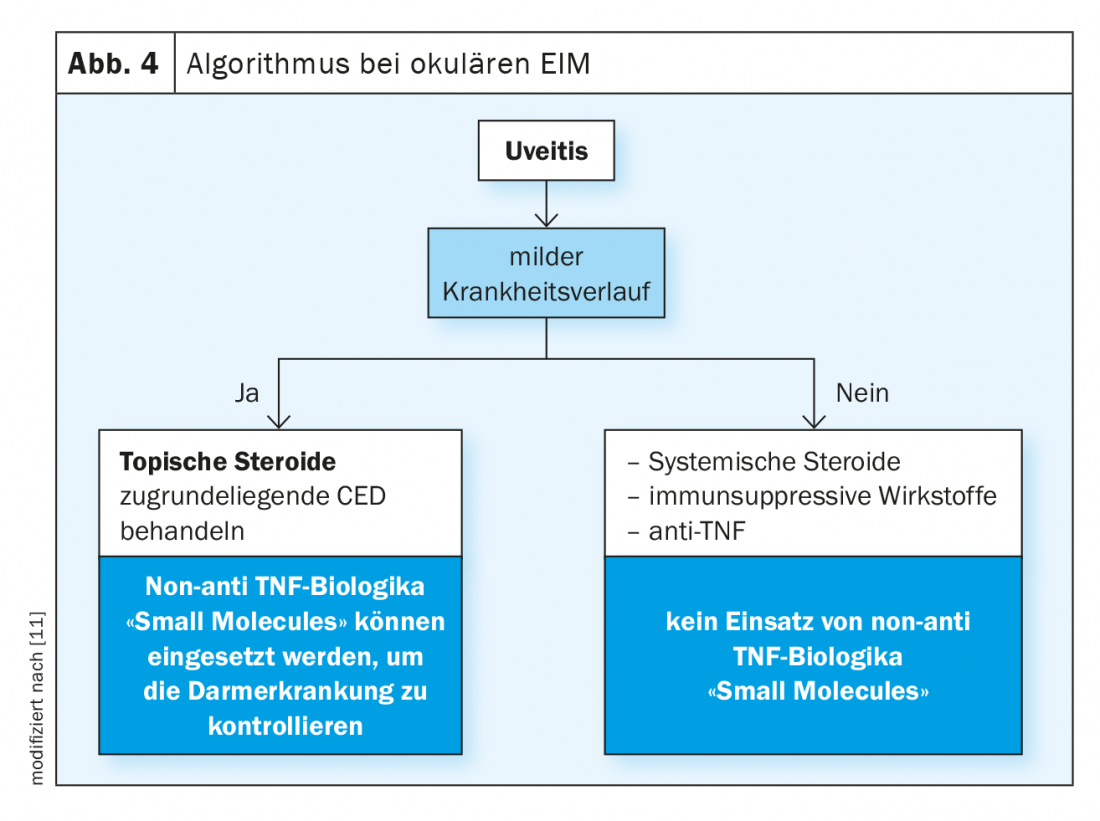

Among ocular manifestations, uveitis is the most common. Topical steroids can be used if the course of uveitis is mild, and treatment of the underlying IBD can also relieve ocular inflammation. For this purpose, non-anti-TNF biologics or “small molecules” are indicated [11] (Fig. 4) . In a severe course, systemic steroids, immunosuppressive agents or anti-TNF are required. Referral to an opthalmologist is recommended for ocular manifesta-tio-ns.

Standard procedures should be used in CED patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), and these are summarized in the box [13]. Following the appropriate recommendations regarding screening and follow-up is extremely important, as PSC greatly increases the risk of colorectal cancer.

Also recommended in IBD patients is regular anemia screening , as anemia is a common comorbidity [14,15]. Laboratory diagnostics should include erythrocyte count (including MCV), ferritin level, transferrin saturation, and CRP. In patients who are currently in remission or have only mild-grade IBD, these parameters should be monitored every 6-12 months, and in those with active IBD, every 3 months. Hemoglobin (Hb) levels below 12 g/dL (women) or below 13 g/dL (men) are anemia, which should be treated by intravenous iron supplementation [2]. The goal is a ferritin level >30 ng/ml. According to the ECCO guideline, iron substitution therapy should be performed in active IBD already at a Ferri-tin level <100 ng/ml.

Take-Home Messages

- Many patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) suffer from disease-associated symptoms outside the gastrointestinal tract.

- Classic extraintestinal manifestations (EIM) that may occur in association with IBD include rheumatologic, ocular, cutaneous, and hepatobiliary symptoms. The latter include primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), which is a significant risk factor for cholangiocarcinoma and colorectal cancer. The most common EIM are rheumatologic conditions (peripheral arthritis, spondyloarthritis).

- Because of the multiple morbidities that can occur in different organ systems, ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease often require an interdisciplinary approach to diagnosis and treatment. Treatment options range from conventional therapy options to modern systems therapeutics such as biologics and JAK inhibitors.

- Anemia is one of the most common comorbidities in patients with IBD. Therefore, this should also be clarified during follow-up and, if necessary, treated by means of iron substitution therapy.

Literature:

- Biedermann L: Chronic inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Modern “state-of-the-art” pharmacotherapy – an update. FAMILY DOCTOR PRACTICE 1/2021, 15-19.

- Vavricka S, Greuter T: Extraintestinal manifestations and comorbidities. eLearning IBDmatters, Module 2, Prof. Dr. med. Stephan Vavricka, PD Dr. med. Thomas Greuter, Slide presentation, Symposium 2021

- Vavricka S, et al: Inflamm Bowel Dis 2015; 21(8): 1982-1992.

- Harbord M, et al: J Crohns Colitis 2016; 10(3): 239-254.

- Hedin CRH, et al: J Crohns Colitis 2019: 13(5): 541-554.

- Vavricka SR, et al: Am J Gastroenterol 2011; 106(1): 110-119.

- Olsson R, et al: Gastroenterology 1991; 100: 1319-1323.

- Saich R, Chapman R: World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14: 331-337.

- Khor B, Gardet A, Xavier RJ: Genetics and pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature 2011; 474(7351): 307-317.

- Vavricka S, et al: Inflamm Bowel Dis 2015; 1794-1800.

- Greuter T, et al: Gut 2021; 70(4): 796-802.

- Vavricka S, et al: J Crohns Colitis 2018; 12(3): 347-354.

- Lindor K, et al: Am J Gastroenterol 2015; 110(5): 654-659.

- Niepel D, et al: Therap Adv Gastroenterol 2018; 11: 1756284818769074.

- Kaitha S, et al: World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol 2015 6(3): 62-72.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2021; 16(9): 4-9