While targeted therapies in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) have been on the rise for years, such an option for KRAS-mutatedtumors has been lacking. The small molecule inhibitor Sotorasib, which targets KRASG12C, could soon close this gap. There is also something happening in the small cell lung cancer (SCLC) pipeline. Among other things, the focus here is on immunotherapy with so-called “bispecific T-cell engagers” (BiTEs).

Lung cancer accounts for more than 10% of all cancer cases and just over 20% of all malignancy-associated deaths. Or to put it more vividly: Every 18 seconds, one person dies of this disease worldwide, 1200 of them every day in Europe. Even if some successes in therapy have been achieved in recent years, there is still much room for innovation. Not only is there a great need for new diagnostic and therapeutic approaches, but their implementation in practice is also in urgent need of improvement.

KRAS as a therapeutic target

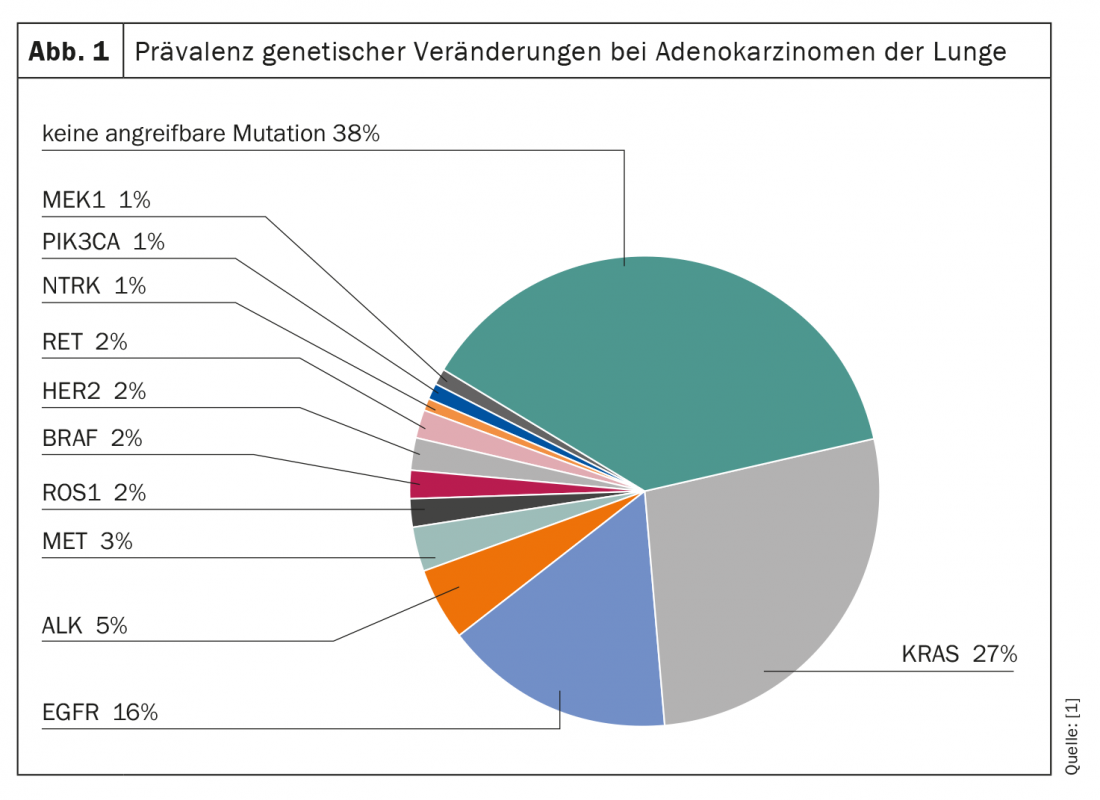

Genetic alterations are common in lung cancer (Fig. 1) . Across all subtypes, the G-protein KRAS represents the most frequently mutated, potentially targetable molecule. Thus, about 27% of all adenocarcinomas of the lung have a mutation of the KRAS gene. However, while other mutations, such as those of the EGFR and ALK genes, are already being targeted therapeutically, KRAS has long been considered an “undruggable target”. In particular, the small size, smooth surface, and absence of suitable binding pockets make selective attack difficult.

The development of the small molecule inhibitor Sotorasib resulted in the first clinically applicable blockade of G12C-mutated KRAS proteins. Approximately 50% of KRAS-mutated NSCLC carry this subtype of the mutation. The new compound binds selectively and irreversibly to the previously thought impossible target and has thus, to a certain extent, initiated a paradigm shift in targeted therapy – not only in lung cancer. Since administration of the first dose in 2018, several promising clinical trial results have already been published. For example, in the Phase II CodeBreaK 100 study, which included 126 patients with at least one prior therapy, disease control was seen in more than 80% of cases when given monotherapy with sororasib, and three patients even experienced a complete response. In 43 patients, tumor volume decreased by at least 30%. Median response persisted for ten months and was detectable at 1.4 months. At the time of the data cutoff, 43% of responders were still on treatment with sororasib. The median progression-free survival (PFS) was also convincing in the analysis of the data. It was 6.8 months under sororasib treatment.

Compared to previous options in second-line therapy of this patient population, the new compound represents a significantly better alternative based on current data. Under current therapeutic regimens, progression-free survival after failure of first-line therapy is approximately 4.5 months with response rates of 20% maximum to second-line therapy. Not only has sororasib been able to raise some hope in the area of efficacy so far, but also in safety and tolerability. Reported adverse drug reactions were generally mild, and there were no deaths from the medication. Only 7.1% of patients had to discontinue treatment due to side effects. Here, the main focus was on diarrhea and nausea. In addition, elevations of liver enzymes and fatigue occurred in some cases.

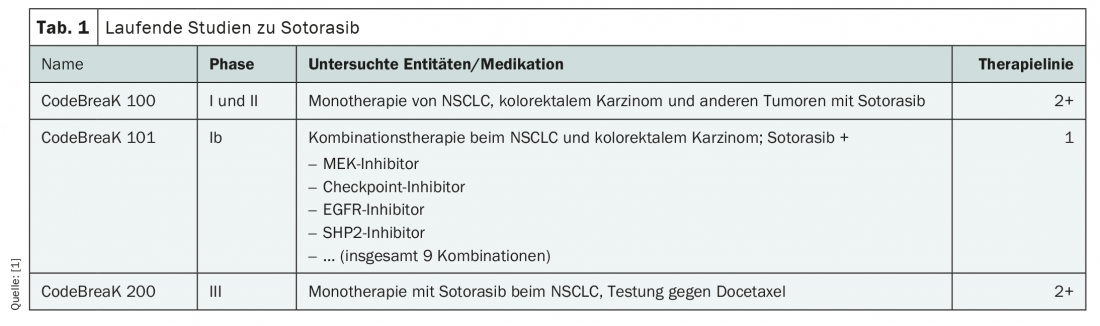

Numerous clinical trials of the new agent are currently underway, both in advanced lines of therapy and in the first-line setting (Table 1). To date, soterasib is the most extensively studied KRASG12C inhibitor. New data are expected as early as this year, in particular from the CodeBreaK 101 Phase Ib study for use as first-line combination therapy in NSCLC and colorectal cancer. An application for approval for second-line treatment of advanced NSCLC with KRASG12C mutation has already been submitted to the European Medicines Agency (EMA).

Quiet hope also for the small cell

As in the absence of targetable mutations in NSCLC, targeted oncologic agents currently have no role in small cell lung cancer (SCLC). This type of lung cancer accounts for approximately 13% of all cases and continues to have an unfavorable prognosis. For more than forty years, chemotherapy has been the focus of treatment; immunotherapeutic approaches have so far failed to convince. However, this could soon change due to the development of bispecific antibodies, so-called “bi-specific T-cell engagers” (BiTEs).

Immunotherapy using BiTEs is based on the activation of the cytotoxic potential of the body’s own T cells. For this purpose, T-cell engagers possess two variable antibody domains: one is directed against a tumor antigen and differs depending on the entity, the other binds CD3 on the surface of cytotoxic T cells. To date, over 3000 patients have been treated with the technology. This is being researched at full speed in the field of both hematological and solid malignancies. Currently, the focus of interest is on the use in prostate carcinoma, small cell lung carcinoma, multiple myeloma and gastric carcinoma. Various combination and sequential treatments are also being tested to prevent potential resistance. Currently, only one BiTE therapy is approved worldwide and in Switzerland for the treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia: Blinatumomab (Blincyto®).

In small cell lung cancer, the variable domain of BiTEs named AMG 757 targets the surface molecule DLL3, which is upregulated on malignant cells. Phase I studies are currently underway. Initial data show a disease control rate of 37% after a follow-up of eleven months. Longer-term data remain to be seen, but there could be some movement here in the near future in an area that has been quiet for a long time.

Real World Check: Uneven standards, availability not guaranteed

As innovative, advanced and effective as new therapies may be, they are often difficult to implement in everyday clinical practice. With more complex therapeutic approaches, a multitude of clinical trials and diverse biomarkers, the demands on the management of patients with lung cancer are increasing. The disease, which is still treated in many places without more precise genetic testing, is increasingly taking on different faces as more and more targets that can be used in therapy are identified. Due to the perception of lung cancer as a histologically, genetically and phenotypically heterogeneous disease, new therapeutic options are emerging at a rapid pace. Integrating this into everyday clinical practice is often difficult, explains Anne-Marie Baird, M.D., president of the patient organization Lung Cancer Europe (LUCE). Personalized medicine does not yet correspond to reality in large parts of Europe. Thus, the positive developments in the field of available substances today unfortunately do not serve all affected persons by far. Accordingly, 31-50% of patients in Europe do not know if they have had biomarker testing. Significant regional differences exist not only in standard diagnostics but also in the availability of effective medications, according to Baird.

The rapid changes in the therapeutic landscape of lung cancer lead to disparity in management and raise many questions about the optimal procedure in clinical practice. Thus, it is often not clear who should be tested for what and when. Also, choosing the right drug and the best sequence can be major challenges today. In addition to expanding access to diagnostics and therapy, Baird cites research into robust predictive markers and the development of clear guidelines regarding genetic testing as goals for the coming years. If these can be implemented, lung cancer patients could soon benefit from even more potent therapies – ideally regardless of where they live. It is quite possible that soterasib and BiTEs will also play a role in this.

Amgen Europe

Source:

- Media briefing “Transforming targeted lung cancer care”, 01.02.2021, Amgen Europe Corporate Affairs

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2021; 9(2): 30-31.