Lynch syndrome, also known as HNPCC (hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer), is the most common inherited cause of colorectal cancer worldwide. In addition to preventive surgery, aspirin is also used for cancer prophylaxis. When should you think about the presence of Lynch syndrome and what are the specific things to do when you suspect it?

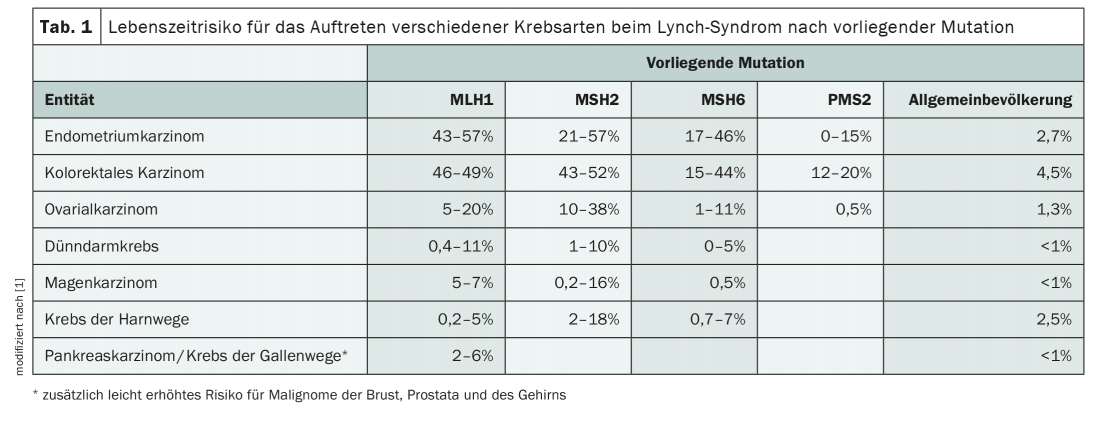

Lynch syndrome, which is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner, substantially increases the risk of developing various types of cancer. In addition to endometrial and colorectal carcinomas, there is also a high incidence of other malignancies such as ovarian, pancreatic or gastric tumors (Tab. 1) . Although the mutations that constitute the HNPCC syndrome are rare in the population, with a prevalence of 1:270 to 1:440, they represent the most common hereditary cancer predisposition of all [1]. Early diagnosis and preventive measures involving the entire family can prevent malignant diseases.

Defective DNA repair

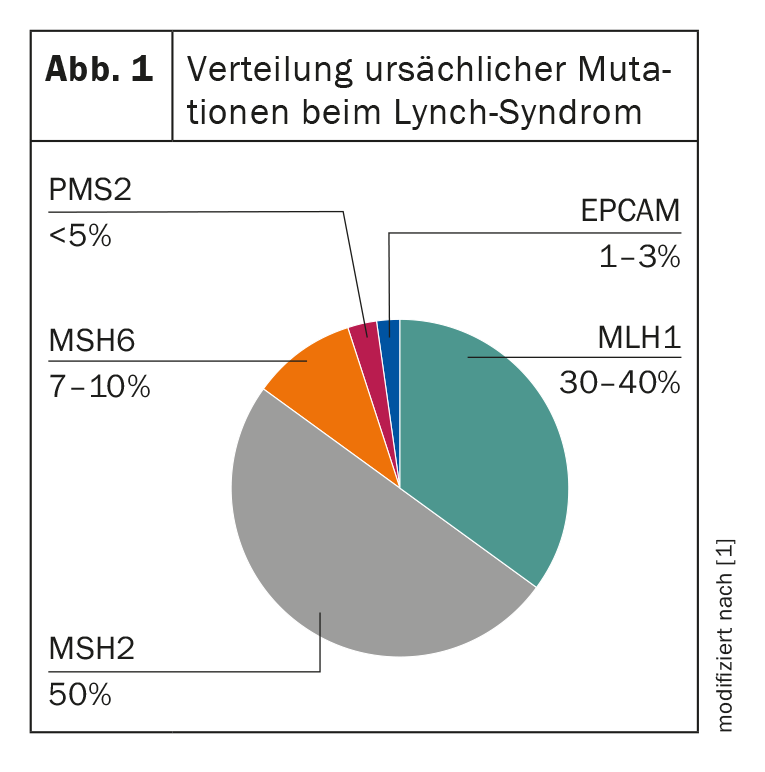

In affected individuals, a genetic defect in DNA repair can be detected, which is reflected in an elongation of repetitive DNA segments – the so-called microsatellites. These differ between tumor tissue and healthy tissue in HNPCC patients, which is called “microsatellite instability” (MSI). Thus, the presence of such MSI with concomitant clinical suspicion is highly suggestive of Lynch syndrome [2]. To date, four DNA mismatch repair (MMR) genes are known whose germline mutations lead to the development of HNPCC: MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2. In addition, a germline deletion of the EPCAM gene can be considered as a causative factor, which also results in a loss of the MSH2 protein in the tumor (Fig. 1) . A corresponding loss of expression in the tumor cells can be visualized by immunohistochemistry and the diagnosis subsequently confirmed by molecular genetics [2]. The identification of the familial mutation is of high importance, since it affects not only the patient himself, but also his whole family. It enables predictive testing of healthy relatives, making preventive measures possible in the first place. Depending on the mutation present and age, the risk of disease differs. This can be calculated individually with the inclusion of the prospective Lynch syndrome database [3].

Due to the autosomal dominant mode of inheritance, there is usually a defective copy of the causative gene in the germ line, which is passed on with a 50 percent probability. If somatic, i.e. random, mutations occur in the second – originally functional – gene copy, the described DNA repair defect develops and thus an accelerated malignant degeneration. Thus, additional unfavorable events are needed for cancer to develop. This mechanism explains the accumulation of colorectal carcinomas in particular, as the dynamics of adenoma formation probably represents an independent risk factor [4].

The wolf in sheep’s clothing

But when does genetic testing make sense? What are the clinical signs that suggest the presence of Lynch syndrome? Unlike other syndromes such as familial adenomatous polyposis coli (FAP), there are no clear phenotypic features in HNPCC syndrome that are suggestive of hereditary disease. There are usually only single adenomas or carcinomas, which are clinically indistinguishable from sporadic tumors. Thus, only with the occurrence of multiple malignancies, due to the often young age of the affected individuals or a striking family history, a Lynch syndrome can be suspected [5]. For example, the median age at colorectal cancer diagnosis is 45 years and in about 30% of cases another typical tumor is added within ten years [6]. In general, HNPCC-associated tumors are mostly adenocarcinomas, and in the colon they preferentially occur in the right hemicolon.

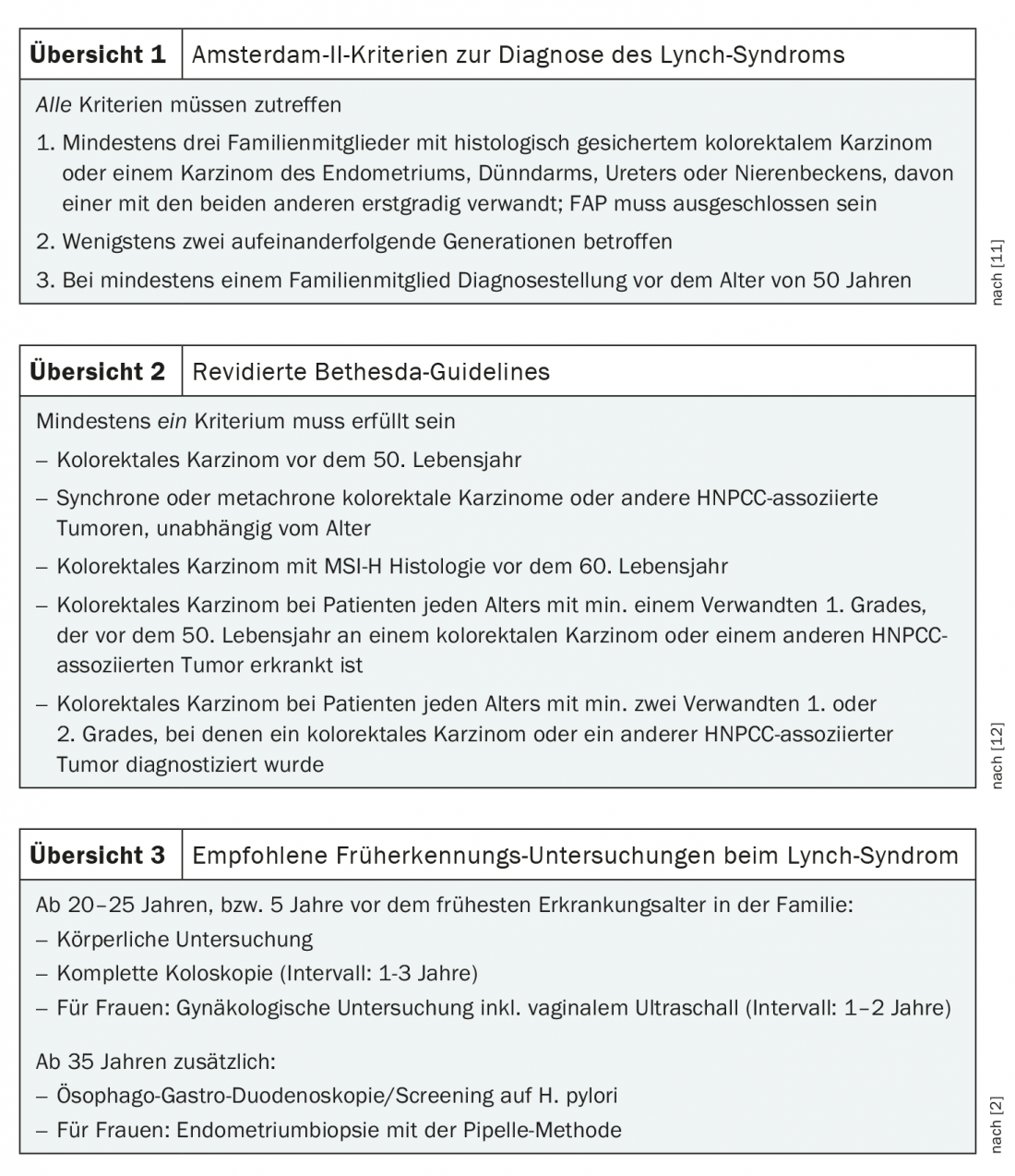

To facilitate identification of patients at risk, several diagnostic scores have been developed over the years, most notably the Amsterdam Criteria and Bethesda Guidelines. In addition, the PREMM model exists for probability calculation. The central element of all these systems is a detailed family history. To meet the Amsterdam II criteria, which are sufficient to diagnose HNPCC, at least three relatives must have Lynch syndrome-associated cancer, at least two consecutive generations must be affected, and at least one family member must have had the disease before age 50 (reviewed at 1) [7]. In less clear-cut cases, the Bethesda Guidelines help identify potentially affected individuals and direct them to appropriate diagnostics (Overview 2). With the increasing availability of MSI analysis, which is now routinely performed for many carcinomas, these guidelines are becoming less important, but they are still relevant in the clinical evaluation of outcomes [7]. Because microsatellite instability does not prove Lynch syndrome, it occurs in 10-15% of colon and 15-20% of endometrial carcinomas [5].

Microsatellite instability detected… now what?

If microsatellite instability or deficiency of MMR proteins is detected in the tumor of a patient suspected of having Lynch syndrome, there is an indication for genetic testing for causative mutations. These, as well as genetic counseling, are mandatory services provided by the health insurance company, provided that the conditions for genetic testing are met [1]. If a mutation is found for which a clear association with the disease is established, targeted testing of family members should also be recommended. In this context, genetic alterations of (as yet) unknown significance are problematic. In this case, prevention is based on personal medical history and family history and not on the result of genetic testing. The procedure is therefore the same as in the case of an inconspicuous finding; family members should not be tested.

In the absence of specific therapies, the treatment of malignancy is primarily guided by the recommendations that also apply to sporadic tumor diseases. However, in advanced stages, checkpoint inhibitors are increasingly used. For example, pembrolizumab is approved as monotherapy for first-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer with high MSI or defective DNA mismatch repair [8]. Regarding the use of additional immunotherapeutics and the value of microsatellite instability as a predictive marker, exciting data can be expected in the coming years.

Prevention and early detection

Genetic evidence of Lynch syndrome results in a long rat tail of recommendations for further cancer screening. These also apply to relatives who are carriers of the corresponding mutation. In addition to a healthy lifestyle and measures for early detection, preventive surgery and medication are also used. Regular colonoscopies and gynecological examinations should prevent colorectal and endometrial cancer. Screening for Helicobacter pylori is also recommended (Overview 3). There is currently no effective screening for ovarian cancer, which is also common, and urothelial tumors. It is therefore all the more important to sensitize those affected to corresponding symptoms and, depending on the tumor disease in the family, to implement additional measures for monitoring.

In some cases, prophylactic hysterectomy with or without adnexectomy is performed after completion of family planning. Extended colon resections are also sometimes used. The bottom line is that the benefit of preventive surgery for Lynch syndrome is unclear and must be weighed on an individual basis [1]. Reliable data are also lacking on the prophylactic use of aspirin, especially on dosage and duration of administration. According to long-term results of the CAPP II trial, daily use of 600 mg acetylsalicylic acid significantly reduces the risk of all HNPCC-associated malignancies after a latency period of approximately four years. This effect seems to last for about ten years even without further administration after two years of administration [9]. A study evaluating lower doses is currently underway with CAPP III.

While much has been accomplished in the genetic diagnosis and further management of patients with Lynch syndrome over the past several years, particularly at centers, the syndrome is likely still underdiagnosed [10]. In order to contribute significantly to better care for those affected, we can do one thing above all else: Think about it.

Literature:

- SAKK: Lynch Syndrome 2021 Consultation Guide. www.sakk.ch/sites/default/files/2020-11/Leitfaden%20Lynch-Syndrom.pdf. (last accessed 08.05.2021)

- UKB, Institute of Human Genetics: HNPCC / Lynch syndrome. www.humangenetics.uni-bonn.de/de/beratung/erbliche-tumorerkrankungen/krankheitsbilder/hnpcc-lynch-syndrom (last accessed 08.05.2021)

- Prospective Lynch Syndrome Database (PLSD) – cumulative risk for cancer by age, genetic variant, and gender in carriers subject to colonoscopy. www.plsd.eu.

- Engel C, et al: Efficacy of annual colonoscopic surveillance in individuals with hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010; 8(2): 174-182.

- Steinke V, et al: Hereditary colorectal cancer without polyposis. Dtsch Arztebl International. 2013; 110(3): 32-8.

- Lynch HT, et al: Review of the Lynch syndrome: history, molecular genetics, screening, differential diagnosis, and medicolegal ramifications. Clin Genet. 2009; 76(1): 1-18.

- Livstone EM: Lynch Syndrome 2019. MSD Manual. www.msdmanuals.com/de/profi/gastrointestinale-erkrankungen/tumoren-des-gastrointestinaltrakts/lynch-syndrom (last accessed 08.05.2021)

- Drug information from swissmedic, Swiss Agency for Therapeutic Products. www.swissmedicinfo.ch (last accessed 08.05.2021)

- Burn J, et al: Cancer prevention with aspirin in hereditary colorectal cancer (Lynch syndrome), 10-year follow-up and registry-based 20-year data in the CAPP2 study: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. The Lancet. 2020; 395(10240): 1855-1863.

- Morrow A, et al: Understanding implementation success: protocol for an in-depth, mixed-methods process evaluation of a cluster randomised controlled trial testing methods to improve detection of Lynch syndrome in Australian hospitals. BMJ Open. 2020; 10(6): e033552.

- Vasen HF, et al: New clinical criteria for hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC, Lynch syndrome) proposed by the International Collaborative group on HNPCC. Gastroenterology. 1999; 116(6): 1453-1456.

- Umar A, et al: Revised Bethesda Guidelines for hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (Lynch syndrome) and microsatellite instability. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004; 96(4): 261-268.

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2021; 9(3): 37-39.