Dermatoses in the genital area are very distressing for those affected. What risk factors are known and what is the current state of knowledge regarding therapy?

“Candida albicans remains the most important pathogen, causing over 70% of all infections,” explained Isabella Terrani, MD, Cantonal Hospital of Bellinzona. Candida are commensals in the lower tract of the female genitalia (vagina, vulva). In addition to newborns and immunocompromised individuals, those with elevated estrogen levels (e.g., due to pregnancy or contraceptives), smokers, diabetics, psoriasis sufferers, atopics, and patients treated with immunosuppressants or antibiotics have an increased risk of infection (candidiasis), the speaker explained. Among the non-Candida bacterial (NCA) strains, C. parapsilosis and C. glabrata are the most common in the etiology of candidiasis [1].

The most important infections and their treatment at a glance

Candida vulvovaginitis (CVV): This is a common infection, with a lifetime prevalence of 75% for women and 5-8% for recurrent CVV, the speaker said. The most common pathogens are Candida albicans (in >85% of cases). In about 5%, the disease is caused by non-Candida bacterial strains, with C. glabrata being the most common pathogen, followed by C. tropicalis and C. parapsilosis.

Typical symptoms of CVV include pruritus, burning sensation at the vaginal outlet and vulva, and possibly inflammatory changes. In the presence of vaginal discharge, the following differential diagnoses should be considered: bacterial vaginosis (Amsel criteria: pH >4.5; gray-white fluor vaginalis; clue cells; fishy odor); aerobic vaginitis (elevated pH); trichomoniasis; STI [2]. Only about one-third of women who thought they had Candida vaginitis had this diagnosis confirmed [3]. Differential diagnostic indications can also be provided by different morphological features that are characteristic of Candida [4]. Symptomatology also depends on age (estrogen levels); premenopausal there is often involvement of the vagina, postmenopausal more of the vulva and intertrigo.

Immunocompetent asymptomatic and partners of patients with vulvovaginitis do not need to be treated, the speaker said [2].

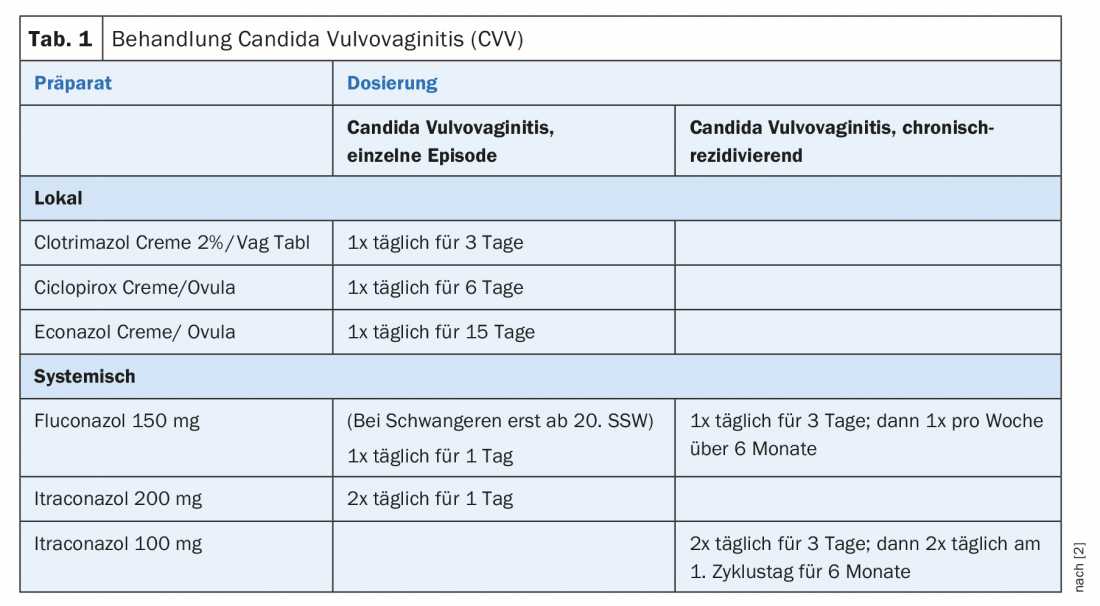

The following criteria are indicative of chronic recurrent Candida vulvovaginitis: at least 4 episodes per year and symptoms for more than 6 weeks, or at least 12 episodes per year and symptoms for at least 100 days per year. Therapy (Table 1) should be given over a longer period than for normal Candida vulvovaginitis. The following interactions are known regarding CVV therapeutics: Oral and anal sex result in poorer response with fluconazole continuous therapy [5]; For RCVV that does not respond to fluconazole, a smear test should be performed [2]; Probiotics as an additional medication may reduce the recurrence rate of CVV [6].

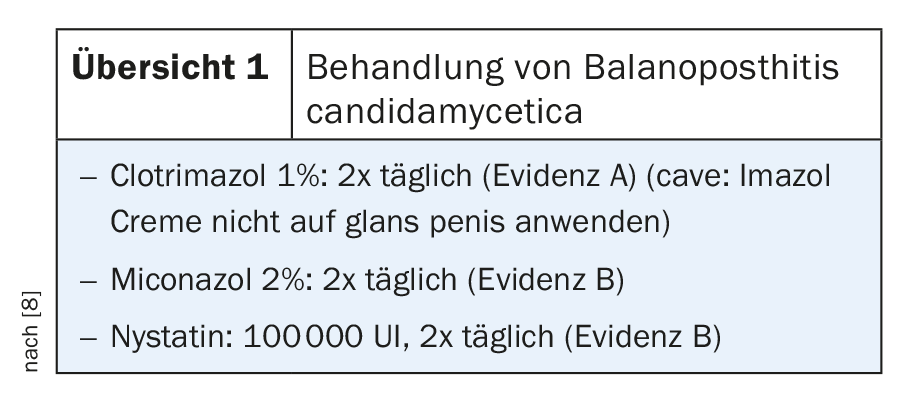

Balanoposthitis candidamycetica: Candida is the causative agent in 20% of all infectious balanitis [7]. The classic symptoms are itching, erythema with a moist shiny surface and white stipple-like coatings. Regarding treatment, clotrimazole 1% has the best evidence (caveat: do not use Imazol cream on glans penis), followed by miconazole 2% and nystatin (review 1).

Intertrigo candidamycetica: This is the most common complication of intertrigo. Typical pathologic changes include satellite lesions and collarettes. The following clinical pictures should be differentiated: Contact dermatitis, psoriasis inversa, Hailey’s disease, tinea inguinalis (scrotum not affected). Risk factors for intertrigo candidamycetica include tight clothing, sweating, and poor hygiene.

Source: Swiss Derma Day, January 16, 2019, Lucerne

Literature:

- Sadeghi G, et al: Emergence of non-Candida albicans species: epidemiology, phylogeny and fluconazole susceptibility profile. Journal de Mycologie Médical 2018; 28(1): 51-58.

- Sherrad J, et al: 2018 European (IUSTI/WHO) International Union against sexually transmitted infections (IUSTI) World Health Organization (WHO) guideline on the management of vaginal discharge. International Journal of STD & AIDS 2018; 29: 1258-1272.

- Ferris GD, et al: Over-the-counter antifungal drug misuse associated with patient-diagnosed vulvovaginal candidiasis. Obstetrics Gynecology 2002; 99(3): 419-425.

- Cassone A: Vulvovaginal Candida albicans infections: pathogenesis, immunity and vaccine prospects. BJOG. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2015; 122(6): 785-794.

- Grinceviciene S, et al: Sexual behavior and extra-genital colonization in women treated for recurrent Candida vulvo-vaginitis. Mycoses 2018; 61(11): 857-860.

- Xie HY, et al: Probiotics for vulvovaginal candidiasis in non-pregnant women. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2017, Issue 11. CD010496. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD010496.pub2

- Borelli S, Lautenschlager S: Differential diagnosis and management of balanitis. Dermatologist 2015; 66(1): 6-11.

- Edwards SK, et al: 2013 European guideline for the management of balanoposthitis. International Journal of STD and Aids 2014; 25(9): 615-626.

DERMATOLOGY PRACTICE 2019; 29(1): 38-39