The course of giant cell arteritis is chronic. Patients often suffer from headache. In order to therapeutically save steroids, the monoclonal antibody tocilizumab has recently been used.

Giant cell arteritis predominantly affects northern Europeans. In an international comparison, the highest incidence rates are found in Scandinavian countries such as Denmark, Norway, Sweden and Iceland. Thus, there is also a strong disparity between northern and southern Europe, according to Prof. Martin Marziniak, MD, Center for Neurological Intensive Care Medicine, Haar (D). The condition mainly affects people of advanced age. The incidence increases over the years of life. Due to demographic developments, it is assumed that there will be more cases in the future. Women are two to six times more likely to develop the disease than men. The cause of the disease is likely to be age-related changes in the immune system and remodeling of the vessel wall [1] – however, the etiology has not been clarified.

As the most common systemic large-vessel vasculitis, giant cell arteritis belongs to a group of inflammatory rheumatic diseases of the blood vessels (vasculitides). These are differentiated according to the size and type of vessels affected using the Chapel-Hill classification. The autoimmune inflammation of the arterial walls in giant cell arteritis is noninfectious and primarily affects the cephalic arteries (temporal artery and ophthalmic artery often involved). It is predominantly T-cell dependent and pathophysiologically characterized by progressive granulomatous inflammation with lymphocytes, macrophages and giant cells (fused macrophages) in the vessel wall – in the course, stenosis or occlusion of the vessel lumen occurs.

Symptoms and Redflags

“Especially because of the ischemic-related complications with impending loss of visual acuity or stroke, numerous warning lights should be flashing for us physicians when dealing with the clinical picture,” the speaker said. The incidence of ocular involvement in the literature is 14-70%. Anterior ischemic optic neuropathy is most common due to occlusion of the posterior ciliary arteries caused by inflammation. This may be accompanied by sudden painless loss of visual acuity, temporary blindness (amaurosis fugax), and visual field loss. According to studies, other known cardiovascular risk factors increase the risk of permanent vision loss.

Ischemic strokes occur in up to 7% of patients (also possible after initiation of glucocorticoid therapy), and there is also a 17-fold risk of thoracic and 2.4-fold risk of abdominal aortic aneurysms. The incidence of aortic aneurysms and dissections increases five years after initial diagnosis and is associated with increased mortality (all-cause mortality increased up to fivefold).

Giant cell arteritis is often symptomatic with headache; in polymyalgia rheumatica, proximally emphasized myalgias of the upper arms and shoulders, morning stiffness, and pain in the pelvic girdle and thigh muscles with limited hip mobility are also present. It is important to put the headache in relation to the giant cell arteritis, i.e., to look for causality. This is given if at least two of the following points are fulfilled:

- Headache is closely temporally related to other symptoms and/or clinical or biological signs of giant cell arteritis or led to diagnosis of the disease

- Either significant increase in headache in the setting of worsening giant cell arteritis or/and significant improvement in headache within three days of high-dose steroid therapy

- Headache associated with scalp paresthesias and/or masseteric claudication (pain in the temporal and maxillary regions, typically occurring with chewing).

Color-coded duplex sonography can provide evidence of inflammatory changes in the temporal arteries and large vessels near the aorta. Characteristic is an echo-poor rim around the affected artery (so-called halo sign). Temporal artery biopsy often shows multinucleated giant cells. CRP and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) are elevated, respectively. Accelerates.

Therapeutic developments

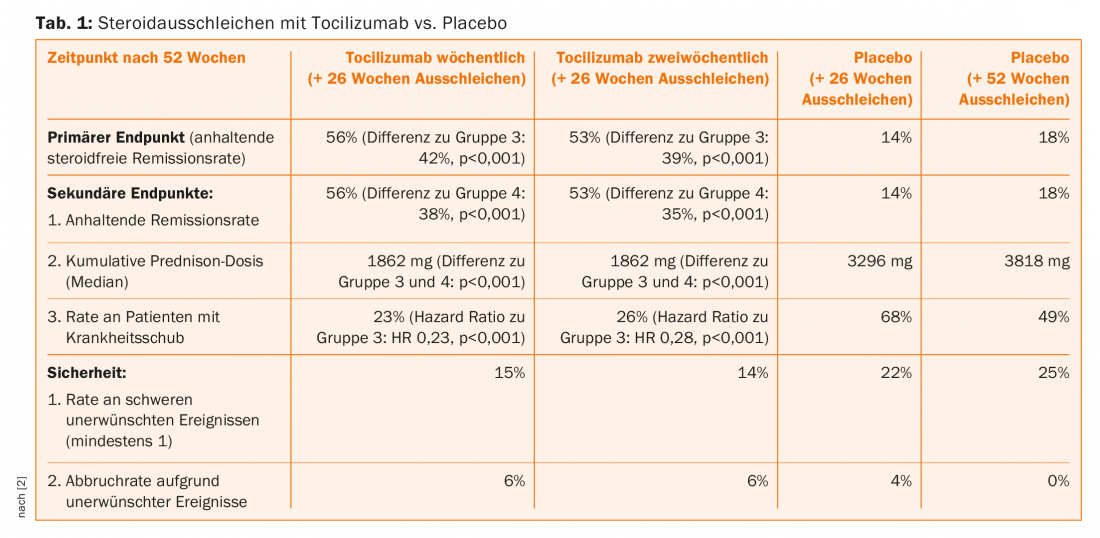

For clinical practice, one would hope for a “sustained remission” of the disease. By definition, this means freedom from recurrence and normalization of CRP from week 12 to week 52 under prednisone sparing as defined in the respective study protocol. The NEJM study of tocilizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody (anti-IL-6 receptor), in giant cell arteritis caused a stir in this context in 2017 [2].

The problem: Prolonged glucocorticoid use is associated with multiple side effects. However, if the glucocorticoid dose is reduced, there is often a risk of recurrence, i.e. a recurrence of signs and symptoms and/or a ESR ≥30 mm/h. Steroid-sparing approaches are therefore of great interest (tocilizumab has anti-inflammatory effects).

In the aforementioned study, therefore, at the same time as the weekly (group 1) or bi-weekly (group 2) subcutaneous tocilizumab administration, the prednisone was phased out over a 26-week period, from an initial 20-60 mg/d to 0. In the randomized placebo comparison groups, the glucocorticoid was also phased out either relatively rapidly, over 26 weeks (group 3), or over 52 weeks (group 4). In the primary endpoint, sustained glucocorticoid-free remission at one year, tocilizumab was significantly superior to group 3 at both doses. The remission rates also exceeded those of group 4 (secondary endpoint) – this with an overall good safety profile without clear signals under the investigational agent (Tab. 1).

Longer follow-up periods are now indicated to provide a clearer picture on remission duration and side effect profile with tocilizumab. Nevertheless, it can already be said that the approach of tapering off steroids with tocilizumab, continuing with mono-tocilizumab, and only reintroducing steroids in the event of a relapse is promising. This is also because the company has many years of experience with the active ingredient in rheumatoid arthritis. In the EU, the substance therefore received approval in the corresponding indication (at the dose of s.c. 162 mg/week) in September 2017. In Switzerland, patients will have to wait for this for the time being.

Source: 6th Three-Country Headache Symposium, March 15-17, 2018, Bad Zurzach, Switzerland.

Literature:

- Mohan SV, et al: Giant cell arteritis: immune and vascular aging as disease risk factors. Arthritis Res Ther 2011 Aug 2; 13(4): 231.

- Stone JH, et al: Trial of tocilizumab in giant-cell arteritis. N Engl J Med 2017 Jul 27; 377(4): 317-328.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2018; 16(3): 43-45.