Pathological obesity is a key risk factor for the development of life-threatening secondary complications. Until recently, bariatric surgery was the only effective method for obesity sufferers to achieve a sustained reduction in body weight and excess fat mass. Fortunately, there has now been a breakthrough in obesity drug treatment – GLP-1 receptor agonists and dual GLP1/GIP agonists have been shown to significantly help reduce obesity and associated health problems.

In Switzerland, about 12% of men and 10% of women are obese and many more are overweight, reported Lukas Burget, MD, Senior Physician, Endocrinology/Diabetology, Lucerne Cantonal Hospital [1]. Various factors promote the development of obesity. These include genetic predisposition and a lifestyle characterized by lack of exercise and an unhealthy diet. However, the causes are more complex than previously thought. “View obesity as a chronic disease and treat it accordingly,” the speaker appealed. The fact that weight loss turns out to be so difficult also has an evolutionary-biological component. In order to be prepared for times of shortage, it was essential for our ancestors to eat as much as possible when an opportunity presented itself [2]. Even today, this behavioral programming is easily activated, but food is almost always available and we move less.

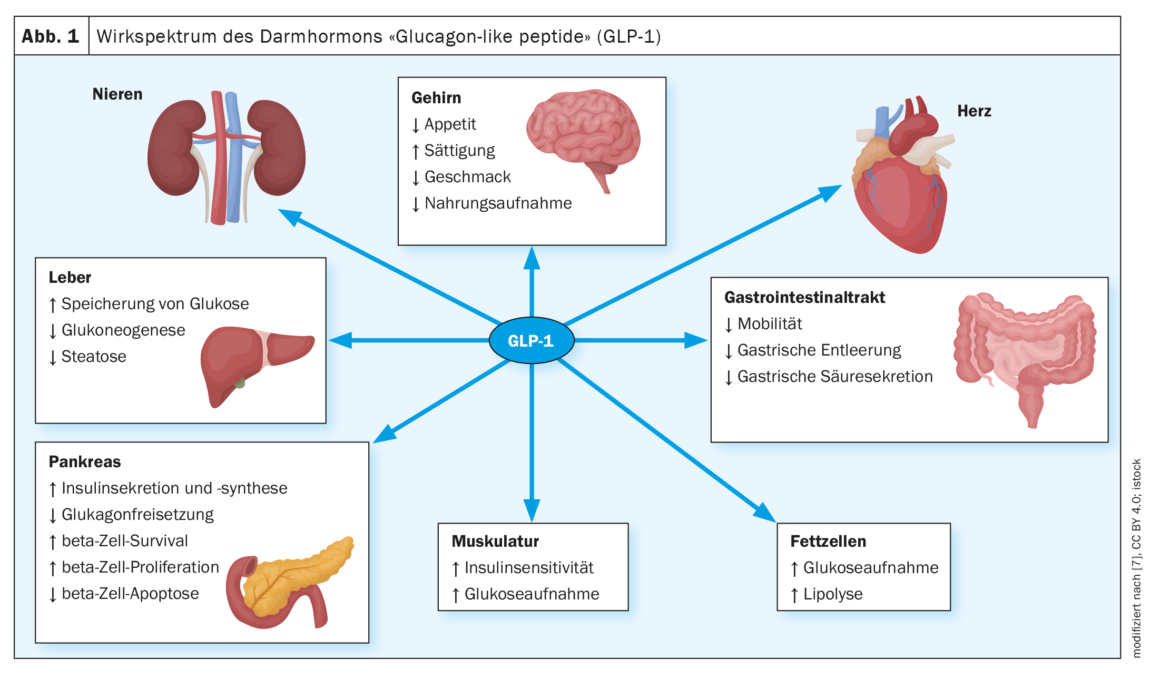

| How does the feeling of satiety arise? The release of cholecystokinin from endocrine cells in the upper small intestine induces satiety. Cholecystokinin controls gallbladder emptying as well as enzyme secretion from the pancreas. Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) from endocrine cells in the lower small intestine also triggers satiety and inhibits gastric emptying when carbohydrates and fats reach it. Moreover, GLP-1 stimulates insulin release from pancreatic beta cells. The pancreatic hormones insulin, glucagon and amylin also have a reinforcing effect on satiety. |

| according to [2] |

Appetite regulation is controlled by complex mechanisms

“Appetite is not a simply constructed system,” Dr. Burget prefaced, explaining the three pillars of appetite: hunger leads to homeostatically motivated eating, pleasure to hedonic eating, and habit to executive eating [1]. The former can be explained biologically: Incretins such as glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) (Fig. 1) and gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP) induce one to eat. Psychological factors or neuropeptides play a role in hedonic eating – for example, dopamine metabolism is involved. While the former can now be relatively well influenced by medication, the modulation of dopaminergic systems is considerably more difficult and involves more side-effect risks. Hedonist-motivated eating can theoretically be influenced by lifestyle modification, for example, by no longer eating dessert. This is easy to say, but implementation is often a problem. Human perception is also susceptible to cognitive biases – so-called “greenwashing,” for example, refers to judging a burger with a lettuce leaf to be lower in calories than a lettuce-free burger. The food industry takes advantage of this and suggests to the consumer that a meal is healthy, but actually contains more calories than one needs.

Obesity as a risk factor for life-threatening secondary diseases

“Obesity is a chronic disease – the body wants its weight back,” Dr. Burget knows. On the one hand, weight reduction must be aimed for and, on the other hand, comorbidities must be treated. Overweight and obesity have been shown to be risk factors for diabetes, cardiovascular disease, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, carcinoma, and many other medical conditions [3]. People with morbid obesity are also more likely to suffer from functional limitations and psychological problems [3]. He said it is known that patients with a BMI of 40 have an average of 14 years shorter life expectancy compared to someone with a normal BMI. But the speaker advises against fixating on a specific BMI as a therapy goal. “Don’t base it on a specific BMI; you want the patient to lose weight and get secondary complications under control,” Dr. Burget emphasized. Although a BMI around 25 is generally considered desirable, in a patient who was able to reduce BMI from 40 to 32 by therapy with a GLP-1 RA, this may be sufficient to reduce secondary complications. “Try to classify what secondary complications the patient has,” he said, referring to the Edmonton Obesity Staging System (EOSS) [4]. This tool analyzes the overall health of a patient and is more informative in terms of predicting survival than BMI. Data from a large US cohort (NHANES – National Health and Human Nutrition Examination Survey) show that the proportion of survivors decreases with increasing EOSS stage – and much more markedly than when categorized by BMI [5].

| Body weight is influenced by numerous external and internal factors as well as peripheral and central regulatory mechanisms. In addition to the individual genetic background, socio-cultural factors and lifestyle, changes in appetite-regulating peptides and regulatory structures in the central nervous system are important factors for disturbances in energy balance. |

| according to [2] |

Secondary complications can be reduced by weight loss

“You can treat these secondary complications,” Dr. Burget explained, citing the example of two patients to illustrate the point: in one, weight reduction of 8 kg reduced HbA1cfrom 8.2 to 5.8, and in the other – a 49-year-old with metabolic syndrome – therapy with liraglutide (Saxenda®) in a BMI reduction from 33 to 29 within 10 months and parallel to this the blood pressure values normalized (no more antihypertensive therapy required) [1,6]. Weight loss of 10% is common with liraglutide, with super-responders achieving up to 15%, the speaker reported [1]. There is evidence of a class effect – for example, semaglutide has similar efficacy – so far only the 1.0 mg dose is available with Ozempic®, but approval of semaglutide 2.4 mg is expected in the near future [1,6]. Tirzepatide has also been shown to be very effective – this dual GLP1/GIP agonist is actually an antidiabetic, but studies in non-diabetics have shown weight loss of up to 22%, the speaker explained [1]. Compared with semaglutide 1 mg, tirzepatide 15 mg proved superior in terms of both body weight and fat mass reduction. And this despite the fact that there were no differences in caloric intake. It is likely that tirzepatide will boost energy consumption somewhat more compared to semaglutide. The possibilities seem to be far from exhausted. In the future, the importance of GLP-1 agonists and dual GLP1/GIP agonists or polyagonists in the treatment of obesity will continue to increase, Dr. Burget said [1].

Literature:

- «Pharmacological Therapies for Obesity», Dr. med. Lukas Burget, SGAIM Frühjahrstagung, 10.–12.5.2023.

- «Die Verführung: Appetit – Hunger – Sättigung», www.sge-ssn.ch/media/tabula_1-15_D-Report.pdf, (letzter Abruf 21.06.2023)

- «Neue Analyse von WHO/Europa bringt überraschende Trends bei der Prävalenz von Übergewicht und Adipositas in der Europäischen Region ans Licht», www.who.int/europe/de/news/item/07-12-2021-

new-analysis-from-who-europe-identifies-surprising-trends-in-rates-of-overweight-and-obesity-across-the-region, (letzter Abruf 21.06.2023) - Sharma AM, Kushner R: A proposed clinical staging system for obesity. Int J Obes (Lond) 2009; 33: 289–295.

- Padwal RS, et al.: Using the Edmonton obesity staging system to predict mortality in a population-representative cohort of people with overweight and obesity. CMAJ 2011; 183(14): 1059–1066.

- Arzneimittelinformation, www.swissmedicinfo.ch, (letzter Abruf 21.06.2023)

- Laurindo LF, et al.: GLP-1a: Going beyond Traditional Use. Int J Mol Sci 2022; 23(2): 739, www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/23/2/739, (letzter Abruf 21.06.2023).

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2023; 18(7): 36–37