Just a glance at the anatomy of the groin is enough to explain the complexity of this part of the body – a veritable crossroads of a wide variety of systems – and also to appreciate the multitude of differential diagnoses that need to be considered in groin pain. In the following, we will go into more detail about possible pathologies.

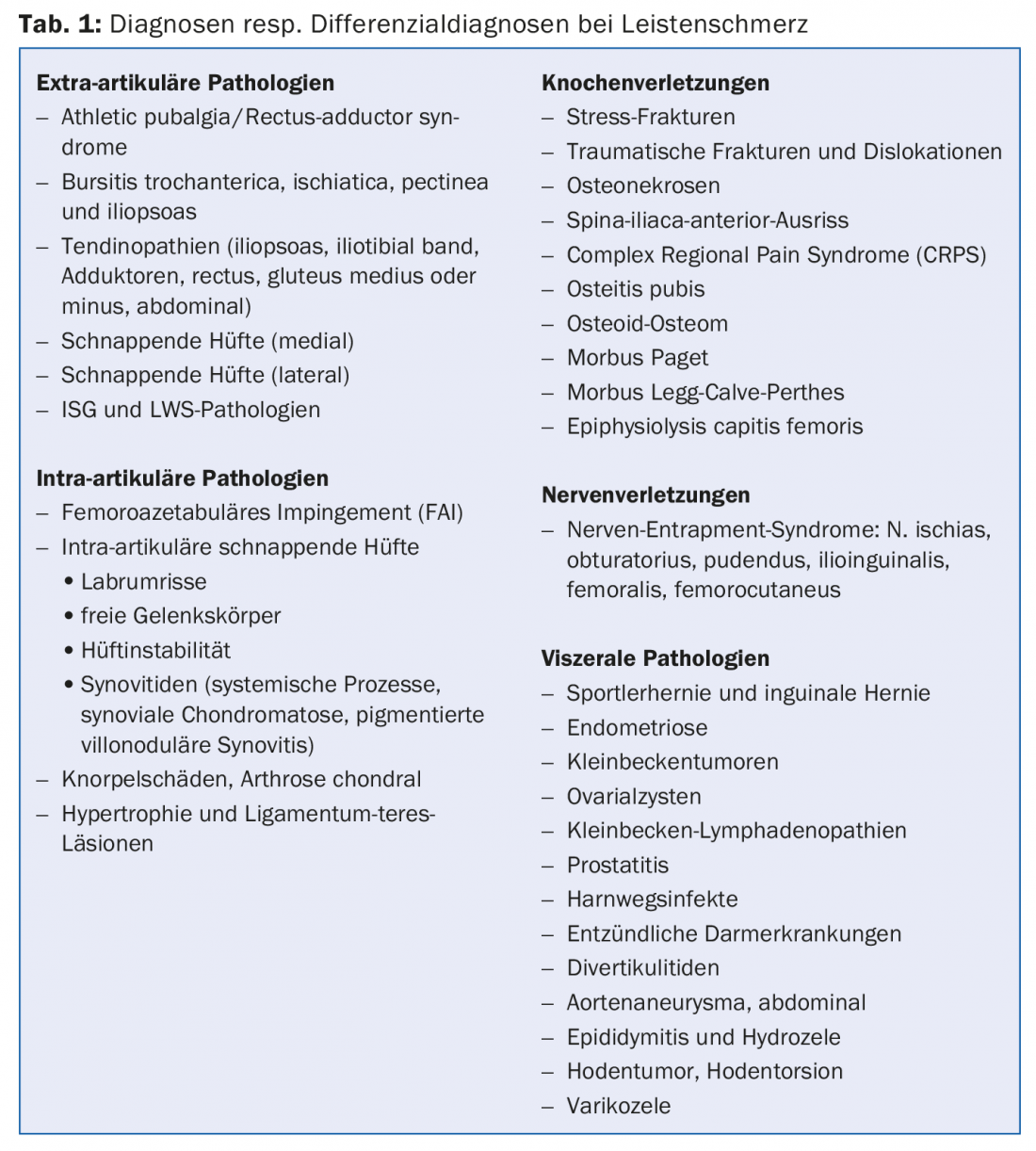

This variety of diagnoses and differential diagnoses (Table 1) also explains why groin pain is quite common in a sports medicine-oriented consultation. In our never-published diagnostic statistics of 5240 diagnoses conducted over more than eight years, “pubalgia” was found in an average of 5% of all cases.

As is so often the case in medicine, the simple principle applies: “What is common is common – and what is rare is rare”. From this banal fact, it is clear that some pathologies are more likely than others. From numerically large and even more homogeneous collectives (sex, age, type of sport) it appears that approx. 50% of the pubalgias are genuine pubalgia atletica, approx. 20% hip complaints, above all the so-called femoroacetabular impingement syndrome, approx. 5% urogenital problems, and approx. 10% muscle tears of the rectus femoris muscle or tears of the spina iliaca anterior.

Accurate diagnosis is challenging but strongly indicated

For the first-consulting physician, it is an exciting challenge to classify this complex clinical picture diagnostically. A careful history makes it possible to distinguish an acute-appearing pain, as in the case of a strain (muscle tear) in the adductor region, from a more gradual-appearing disorder. Questions should also be asked about coughing and sneezing pain, pain during urination or sexual intercourse, as well as about radiation. However, clinical examination remains the most important step in finding the cause of groin pain. When standing from the front, pelvic (and shoulder girdle) horizontality, lower extremity morphology, toe and heel stance bilaterally, hernial ports, and from the side, pelvic tilt, lordosis, finger-to-floor distance are assessed, and from the back, pelvic girdle horizontality, ISGs, Trendelenburg sign, and back mobility in all directions are assessed again.

Sitting on the edge of the bed, the so-called muscle testing is performed looking for “shortening” and weakening, then in the supine position the lasègue, reflexes, strength and sensitivity.

Then the problem is approached with a close examination of the hips, abdominal muscles, adductors, iliopsoas muscle and symphysis. The muscles attaching to the pelvis should be tested with force testing against resistance. This rather detailed examination can be easily realized in six to seven minutes. It should already allow some specification of the diagnosis and prepare the choice of complementary objective measures such as sonography, X-ray or MRI.

Without a precise diagnosis, any treatment attempt must remain purely symptomatic rather than causal. Given the complexity, however, it is not surprising that the therapeutic spectrum for groin pain – one of the most common “catch-all” diagnoses in sports medicine – is too often limited to analgesic infiltration. Since the affected structures are found in a relatively confined space, a therapeutic bull’s-eye can occasionally be scored by the injection, even without a diagnosis, if the dosage is high enough. But just occasionally!

Possible diagnoses

FAI: In the following, we would like to describe three diagnoses in a little more detail. First, the so-called femoroacetabular impingement syndrome (FAI) – not least because FAI was first presented in its present form in Bern about 13 years ago. This is a conflict between the femur, more specifically the femoral head, and the pelvic socket, which often manifests as groin pain. It is not uncommon for patients with this change to be treated for a longer period of time with the diagnosis of “adductor strain.” The pathomechanism is based on a morphologic shape variant with either aspheric femoral head (CAM shape) or too prominent acetabular rim (PINCER shape). These structural anatomical changes lead to early painful impingement between the head and the acetabulum and “pinching” (impingement) during intense stress on the hip joint. It is therefore not surprising that this clinical picture, with damage to the joint lip and the cartilage in the hip joint, occurs frequently in young and athletic individuals. The sport of ice hockey seems to be particularly affected.

A strong presumptive diagnosis can be made clinically: Painful restricted internal rotation in flexion and reproduction of groin pain on the two provocation tests FADIR (flexion-adduction-internal rotation) and FABER (flexion-abduction-external rotation) are highly suspicious for FAI. The final diagnosis is made by X-ray, but mainly by means of arthro-MRI. Therapy often begins conservatively with active physical therapy, which focuses on finding optimal muscular balance around the hip and improved dynamic control of the lower extremity. Likewise, attempts are made to educate the patient to better manage their hip joint motion amplitude. A break from competition is almost unavoidable.

It is generally accepted that if symptoms persist after two months under conservative measures, the surgeon must be consulted. Whereas FAI used to be approached exclusively with open surgery – which is still the gold standard – hip arthroscopy, which produces decent results, has now also become established. However, this intervention is reserved for specialists.

It is important to be aware of this syndrome and to diagnose it early, because there is clear evidence that FAI is a door opener for coxarthrosis.

Athlete’s hernia: The second clinical presentation we have selected is the so-called athlete’s hernia, a term that is quite common in German-speaking countries. If a young athletic patient complains of a pressure-painful inguinal canal, a pressure-painful pubic tuberosity, and pressure-sensitive hip adductors, and also has a dilated external inguinal ring (with radiation of symptoms to the perineum, genital and medial thigh areas), then athlete’s hernia should be considered.

Leading symptoms are tenderness in the pubic region and palpable painful posterior wall of the inguinal canal. This discomfort is aggravated by sudden exertion, coughing, sneezing, sexual activity, muscular exercises such as sit-ups or adductor training. The whole problem is explained by a circumscribed weakness in the medial part of the posterior wall of the inguinal canal, resulting in a localized protrusion of the transverse fascia into the inguinal canal. For their part, these changes lead to compression of the ramus genitalis of the genitofemoral nerve during tension of the abdominal muscles or abrupt movements (sports), which explains well the radiation of the pain. Further, retractions of the rectus abdominis muscle occur with pain in the pubic bone. As clear as the matter seems to be, the dispute between experts in the field is still ongoing!

The diagnosis is based on the clinic, i.e. also on the experience of the examiner, and on sonography. Therapy is very often surgical with stabilization of the posterior wall of the inguinal canal, often supplemented with neurolysis of the compressed nerve. In a large controlled series, freedom from symptoms was achieved in 80% of athletes within 14 days.

Osteitis pubis: Osteitis pubis would be another differential diagnostic thought. Without going into details here, this should be thought of and, if necessary, pointed out when ordering the MRI. The bony stress response can be readily identified by the presence of bone marrow edema, usually bilateral, in the symphysis and pubic branches.

Conclusion

Treating the groin pain of the athlete is undoubtedly a difficult task for any doctor – but also a very interesting one. It is best solved as a team, actually a very “sporty thing”.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2016; 11(8): 4-5