The topic of contraception is also important in family practice, and the existing guidelines on hormonal contraception provide important guidance. When implementing them in practice, the main thing is to determine any contraindications and assess the risk of thromboembolism. When selecting a preparation, the desired side effects can certainly be taken into account, e.g. effects on acne, bone density or premenstrual syndrome.

The topic of contraception confronts all (family) physicians who care for patients of reproductive age: whether indirectly, when it comes to ruling out or considering interactions, or directly, when advising women or couples about contraceptive methods and when contraception is to be initiated and monitored. On the one hand, the available new guidelines offer guidance, but on the other hand, they also require that conventional education and dispensing practices be partially changed and adapted. In this context, it is certainly important to carefully review the indication, to provide detailed and comprehensive information, and to document well with regard to an indication-appropriate use and an “informed decision”. At the same time, however, this approach should not unnecessarily raise the threshold of contraceptive accessibility, as this could have a negative impact on the prevention of unwanted pregnancies.

This article presents the existing guidelines and explains their practical application. In addition, a few aspects that are crucial when choosing a preparation are discussed.

On contraception, guidelines exist in the form of an expert letter on combined hormonal contraceptive (CHC) prescribing practices and a position paper on emergency contraception.

SGGG expert letter on contraception

The expert letter (No 35, updated version of June 2013) was written under the direction of the Quality Assurance Commission of the Swiss Society of Gynecology and Obstetrics (SGGG) and discusses the issue of thrombosis risk [1]. At the same time, the SGGG also provides a handout for physicians, a checklist for prescribing, and an information sheet for users in numerous languages [2]. At the end of 2013, Swissmedic also initiated a harmonization of professional and patient information for hormonal contraceptives with the aim of enabling physicians and their patients to make an informed decision regarding the choice of contraceptive method.

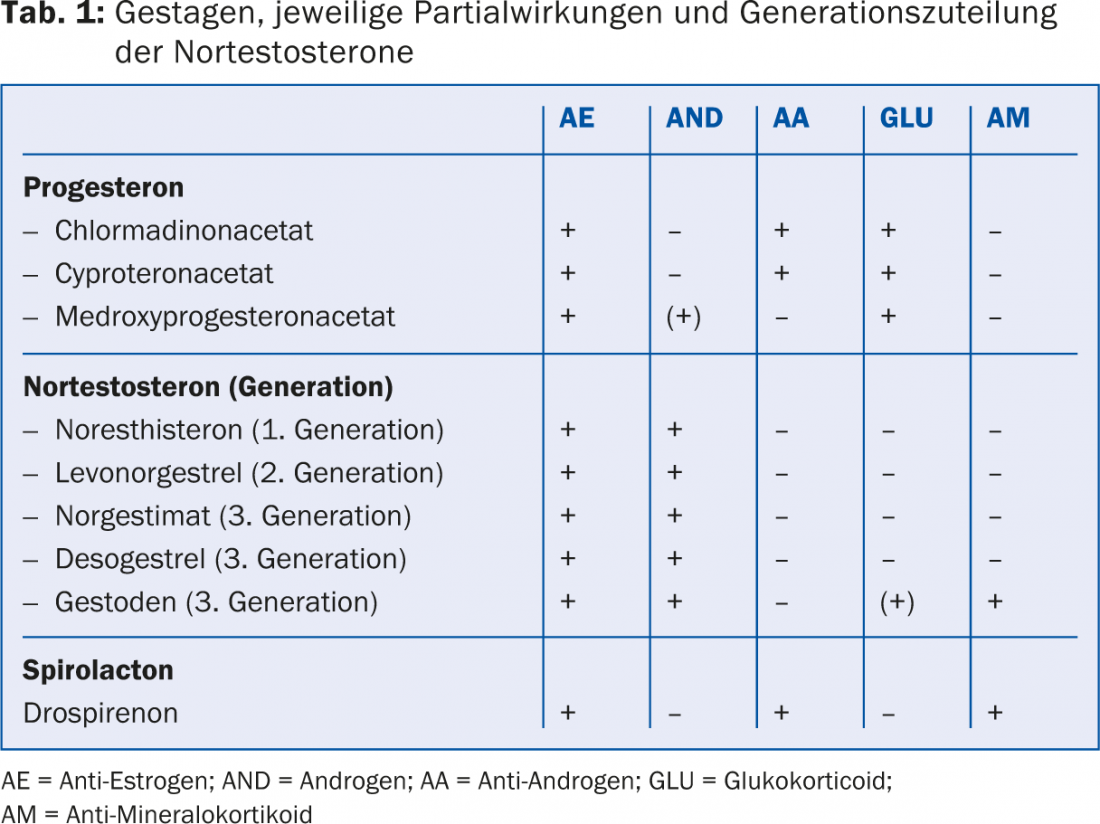

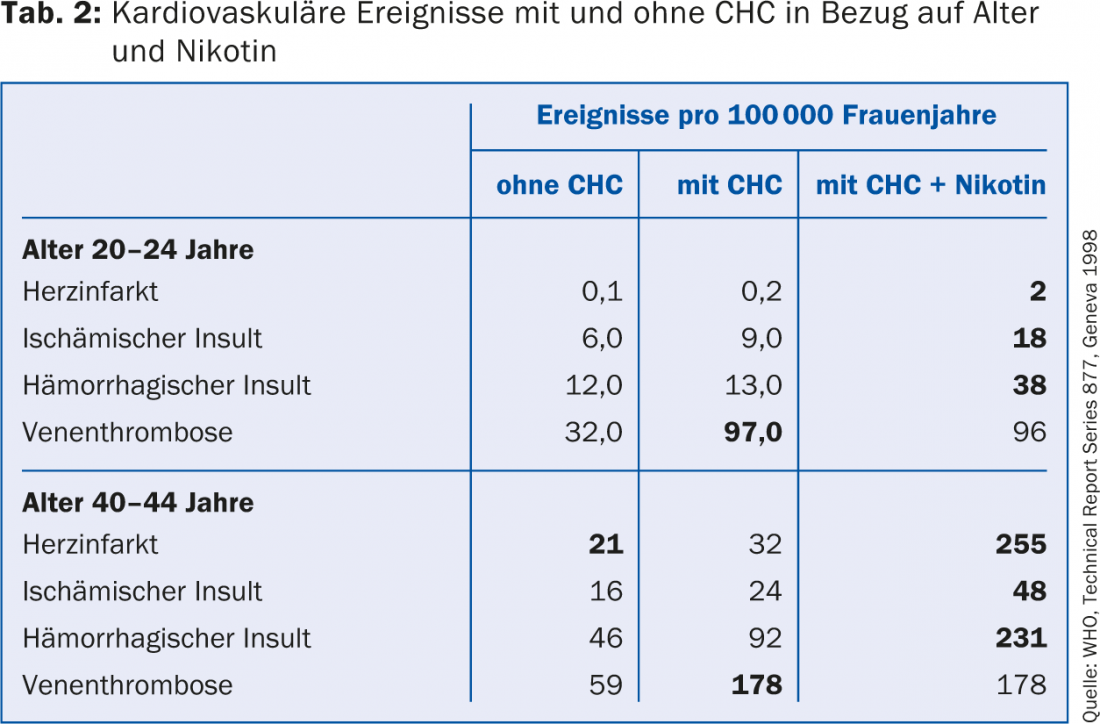

The risk of thromboembolism on CHC has been reduced over the past 30 years with the development of micropills containing ≤35 μg ethinylestradiol (EE). In the following period, however, there were indications that the progestin combined with the EE influences hemostasis and the resulting risk of thrombosis. Among these, contraceptives containing third-generation progestins (gestodene and desogestrel) and the later-introduced drospirenone appear to be associated with a slightly higher risk of thrombosis. For the much rarer but often much more fatal arterial events such as myocardial infarction or cerebrovascular insult, on the other hand, there seems to be no difference between the progestins of the different generations (Tab.1). Table 2 provides an orienting overview of the risk of thrombosis depending on the age of the woman and CHC use without and with nicotine use.

Based on the now almost two million woman-years of data and including five additional studies published in 2011 (evidence level IIa-IV), the main findings are summarized in the expert letter as follows:

- The rate of thrombosis is highest in the first year of use of a CHC.

- The risk of thrombosis under CHC increases with age. It is twice as high for women aged 30-34 years as for women younger than 20 years (age 30-34: 6 -10 thromboses per 10,000 woman-years). For women over 40, the risk is four times higher!

- CHC with desogestrel, gestodene, cyproterone acetate, and drospirenone are associated with a twofold higher relative risk of venous thromboembolism compared with CHC with levonorgestrel (LNG).

- The increase in the risk of thrombosis also applies to the transdermal and vaginal modes of application of hormones.

- Obesity (BMI >30 kg/m2) leads to a doubling of the risk of thromboembolism.

- Several risk factors have a cumulative effect on the risk of deep vein thrombosis (VTE).

The expert letter specifically notes that combination preparations with cyproterone acetate have a significantly higher risk of thrombosis than those with levonorgestrel and are therefore approved only for the treatment of women with androgenization symptoms with concomitant contraceptive needs [3].

Position paper on emergency contraception

The position paper on emergency contraception (NF contraception) was written by the Interdisciplinary Expert Group on Emergency Contraception (IENK) and the Contraception Commission of the Swiss Society for Reproductive Medicine (SGRM) and reflects the current recommendations on the use of available preparations for postcoital interception [4]. The main findings can be summarized as follows:

- Three efficient methods are available today: NorLevo® (LNG 1.5 mg), ellaOne® (UPA 30 mg) and the copper IUD.

- The efficiency of the copper coil is the greatest, that of LNG seems to be slightly lower than that of UPA.

- NorLevo® is limited to use within 72 hours of unprotected intercourse; ellaOne® and the copper IUD can be used until after 120 hours have elapsed.

- The advantages of NorLevo® are that this “morning-after pill” is available without a prescription and also for under-16s, that there are no contraindications according to the WHO, and that it can be used several times in the same cycle and also during lactation.

- There is evidence that the efficacy of NF contraception with LNG and UPA is reduced in obese women, and this effect appears to be stronger with LNG than with UPA.

Significance and implementation of the guidelines in everyday practice

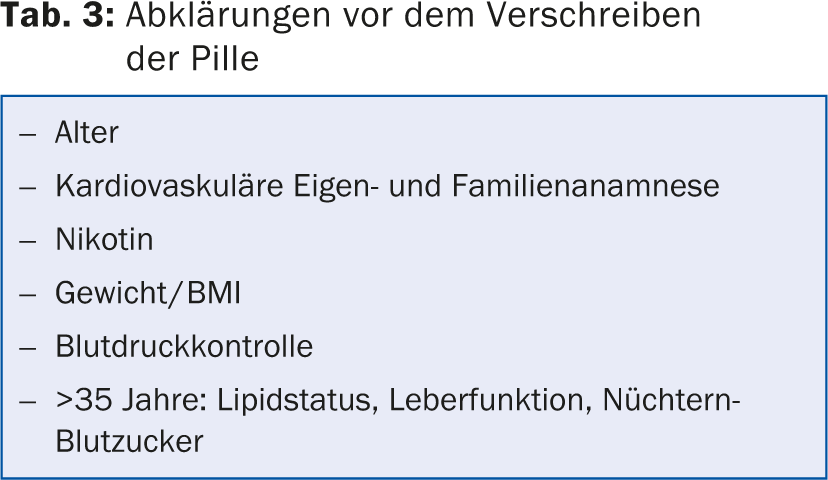

The expert letter and especially the study results on which it is based highlight the importance of taking a careful history and clinically assessing the individual risk for cardiovascular events in every (prospective) CHC user. Table 3 lists the most important clarifications that should be made before prescribing. At the same time, there is no reason to stop low-dose CHC in a woman who is healthy, does not smoke, and has no other risk factors based solely on her age (>35 years), as was often done in the past. In such cases, a CHC can also be used up to the age of 50.

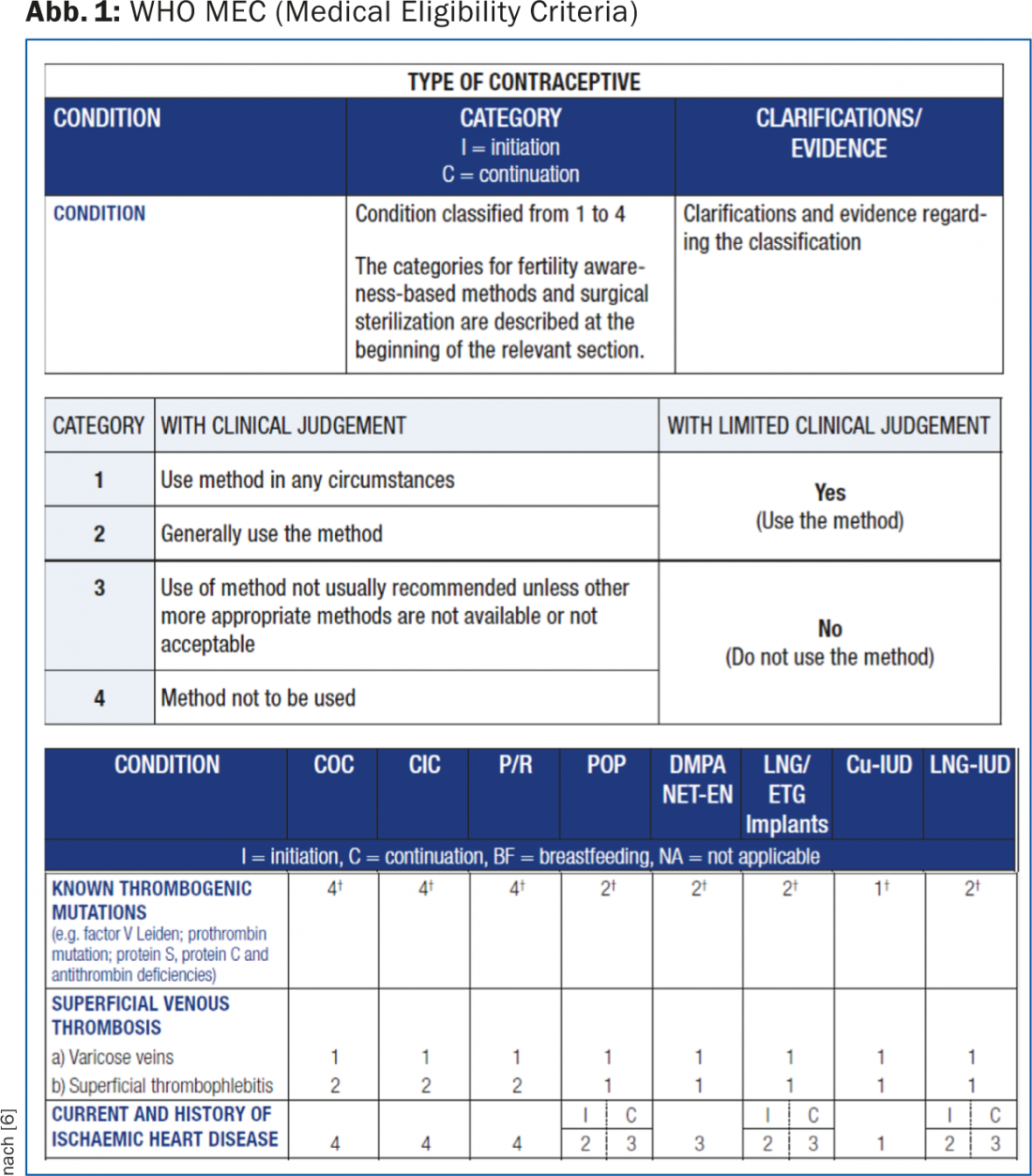

The handout for physicians provides practical, step-by-step guidance on how to proceed with the initial prescription of a CHC and includes a list of absolute contraindications to their use. Another helpful tool for clarifying any relative or absolute contraindications is the WHO Medical Eligibility Criteria (MEC) [5]. They are available online and include evidence-based categorization into four categories (1 = always applicable; 2 = benefits outweigh risks; 3 = risks outweigh benefits; 4 = not applicable) for all hormonal contraceptives, as well as copper and LNG IUDs, not only with respect to thrombosis risk but also with respect to a variety of other medical conditions (Fig. 1) [6].

The SGGG checklist is used to check whether contraindications exist and for documentation in the patient’s file. The patient, in turn, can be given the user sheet also provided by the SGGG. This contains, among other things, a list of those symptoms for which medical contact should be made or the use of the CHC should be suspended immediately. On the one hand, this list ensures that each user has the necessary information, but at the same time, the listing of possible symptoms and alarm signs can also confuse the user. Accordingly, it is important to properly weigh the risks during counseling – also to prevent a hasty discontinuation of a CHC and the resulting risk of an unwanted pregnancy.

Relevant for practice beyond official guidelines

The risk of a cardiovascular event is small in absolute terms, especially in young women, so that the increase in risk from the use of a third-generation progestogen is also not significant. For this reason, and especially with regard to adherence, the choice of preparation must also take into account which concomitant effects are welcome or, conversely, undesirable.

CHC in acne: All CHC can have a fundamentally positive effect on acne, in that EE increases the level of sex hormone-binding globulin, leading to a decrease in active free testosterone. At the same time, however, the first- and second-generation progestins have a partial androgenic effect (Tab. 1), so that their use is problematic in acne requiring treatment. In these cases, an antiandrogenic progesterone derivative (cyproterone acetate, chlormadinone acetate) or drospirenone should preferably be chosen as the progestogen component.

CHC in premenstrual syndrome (PMS): the tolerability of CHC in women with PMS is variable but often rather poor. Regarding the effect of CHC-particularly with drospirenone as the progestin component-on PMS, a Cochrane Review concluded that CHC with drospirenone appear to reduce symptoms of premenstrual dysphoric syndrome (PMDD) [7]. At the same time, reference is made to the sometimes impressive placebo effect. There are no data on efficacy beyond a use period of three months, and drospirenone has not been shown to work better than other progestins.

Effects of CHC on bone density: for possible effects on bone density, the EE dose is relevant. CHC with 20-30 μg EE inhibit bone remodeling in all age groups studied, although this has not been shown to have a negative effect in women over 30 years of age. In adolescents, on the other hand, peak-bone-mass formation may be impaired with CHC containing ≤ 20 μg EE, so preparations containing 30 μg EE should be preferred for adolescents.

Interactions of CHC with other medications: Interactions with other medications may interfere with the contraceptive effect of CHC and therefore must be considered. The interaction usually occurs through enzyme induction. This is well known for antiepileptic drugs, and CHC should not be used in combination with antiepileptic therapy [5]. St. John’s wort preparations also lead to a relevant enzyme induction, namely of cytochrome P 450 3A4, so that the additional use of a barrier method should be recommended for contraception with CHC [8]. The use of most antibiotics is comparatively insignificant. The WHO MECs are also a helpful reference with regard to interactions.

CONCLUSION FOR PRACTICE

- For first-time CHC prescribing and to ensure informed decision-making, careful exclusion of contraindications, comprehensive information, and good documentation are recommended.

- For healthy, young women with acne requiring treatment, CHC with drospirenone, chlormadinone acetate, or cyproterone acetate are best tailored.

- To avoid affecting peak-bone mass, adolescents should not be prescribed CHC with <20 μg EE.

- St. John’s wort preparations can lead to relevant enzyme induction, so that an additional barrier method should be recommended for contraception with CHC.

- For emergency contraception, ellaOne® is more efficient and effective up to 120 hours after unprotected intercourse, but NorLevo® continues to offer a low-threshold, over-the-counter alternative.

Literature:

- Quality Assurance Commission of the Swiss Society of Gynecology and Obstetrics SGGG. Expert Letter No 35: Thromboembolism Risk under Hormonal Contraception. 2013.

- Swiss Society of Gynecology and Obstetrics SGGG. http://sggg.ch/de/members_news/1005.

- Vasilakis-Scaramozza C, Jick H: Risk of venous thromboembolism with cyproterone or levonorgestrel contraceptives. Lancet 2001; 358(9291): 1427-1429.

- Position Paper on Emergency Contraception in Switzerland. 2014; www.sante-sexuelle.ch/wp-content/uploads/ 2014/03/PositionPaperNK_March14_en_def.pdf.

- Department of Reproductive Health, W.H.O., Medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use Fourth edition. Fourth edition ed. 2010.

- www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/family_planning/9789241563888/en.

- Lopez LM, Kaptein AA, Helmerhorst FM: Oral contraceptives containing drospirenone for premenstrual syndrome. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews 2009; 2: CD006586.

- Hall SD, et al: The interaction between St John’s wort and an oral contraceptive. Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics 2003; 74(6): 525-535.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2014; 9(11): 20-23