In the case of symptoms typical of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), initial comprehensive diagnostics with erudition of alarm signs, colonoscopy if necessary, and in particular the exclusion of sprue are of decisive importance. Treatment of IBS includes detailed education of the patient about the nature and essence of the disease, as well as general recommendations on diet, nutrition and lifestyle. Drug therapy depends on the subtype and the symptoms, but the therapeutic gain over placebo is often only 15-20%. Linaclotide is a new, promising but costly drug for previously refractory cases with IBS-C that also has a pain modulating effect.

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a condition in which the colon is irritated. Irritable Bowel Syndrome [IBS]) is the most common chronic gastrointestinal disorder. Approximately 5-11% of the general population is affected, usually between the third and fifth decades of life, women about twice as often as men. Although probably only 20-50% of affected patients consult a physician, the clinical picture is the basis for about 40% of consultations with gastroenterologists and still for 2% of all visits to the general practitioner. The impairment of quality of life by the symptom complex may be as marked as in severe organic disease.

Symptoms and pathophysiology

Irritable bowel syndrome is characterized by chronic recurrent, but sometimes only intermittent, abdominal pain or discomfort that typically improves after defecation and is associated with a change in stool frequency or consistency, with no explanation for these complaints by an underlying organic, infectious, or metabolic disease or drug side effect [1]. Three subtypes are distinguished, depending on whether symptoms consist primarily of constipation (IBS-C, “constipation”), diarrhea (IBS-D), or primarily of pain or changing stool consistency (IBS-A, “alternating,” or also IBS-M, “mixed”). Functional abdominal complaints without pain are considered separate entities (functional diarrhea/abstipation), with significant overlap [2].

The underlying pathophysiology is not yet fully understood. Although changes in gastrointestinal motility have been described in IBS patients, no specific motility pattern has been identified. Rather, the decisive factor seems to be visceral hypersensitivity, i.e., an increased and painful perception of physiological stimuli from the gastrointestinal tract. Previous gastrointestinal infections or a change in the microbiome (less lactobacilli and bifidobacteria) as well as the mucosal immune system and psychosocial factors also play a role.

Diagnostics and differential diagnoses

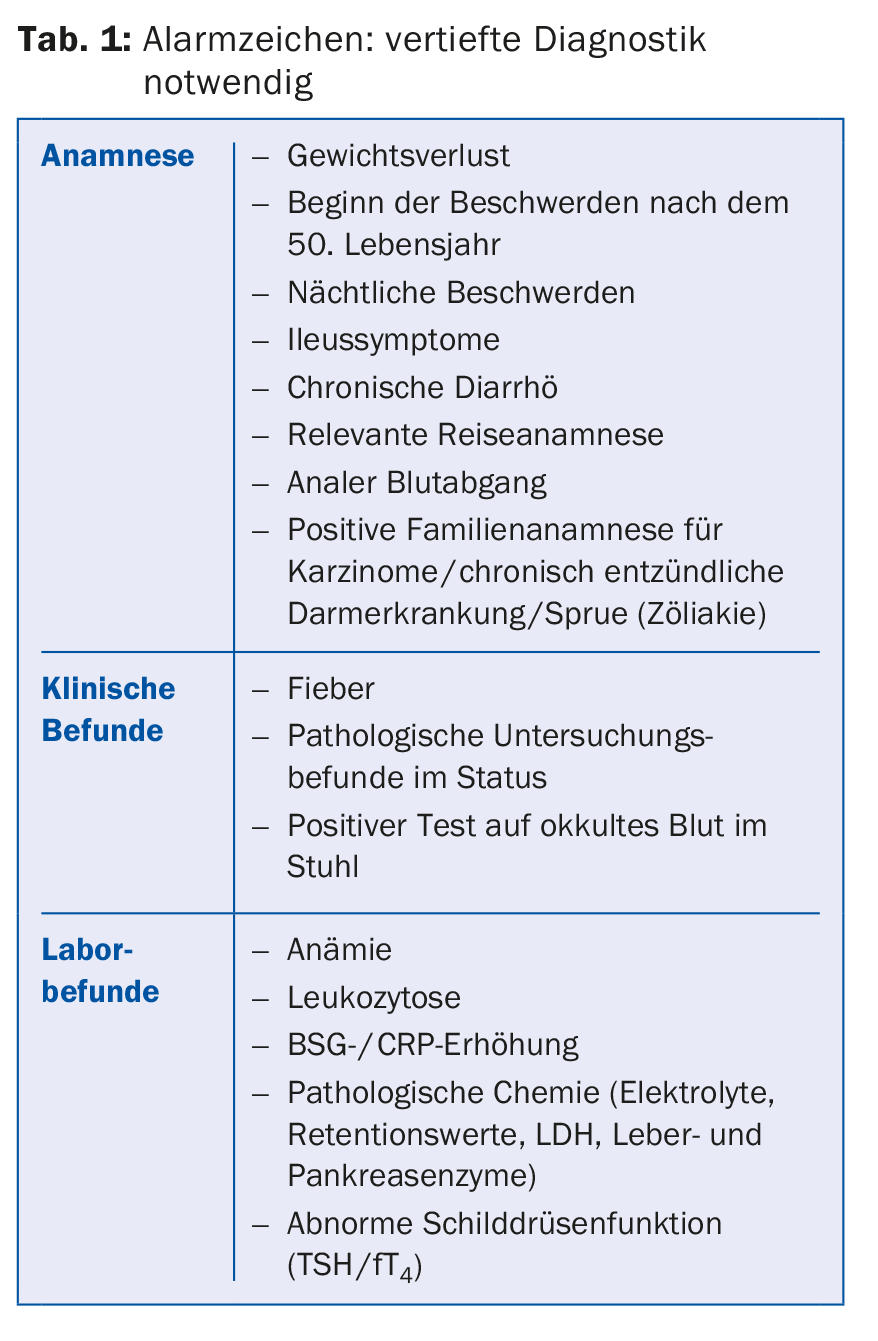

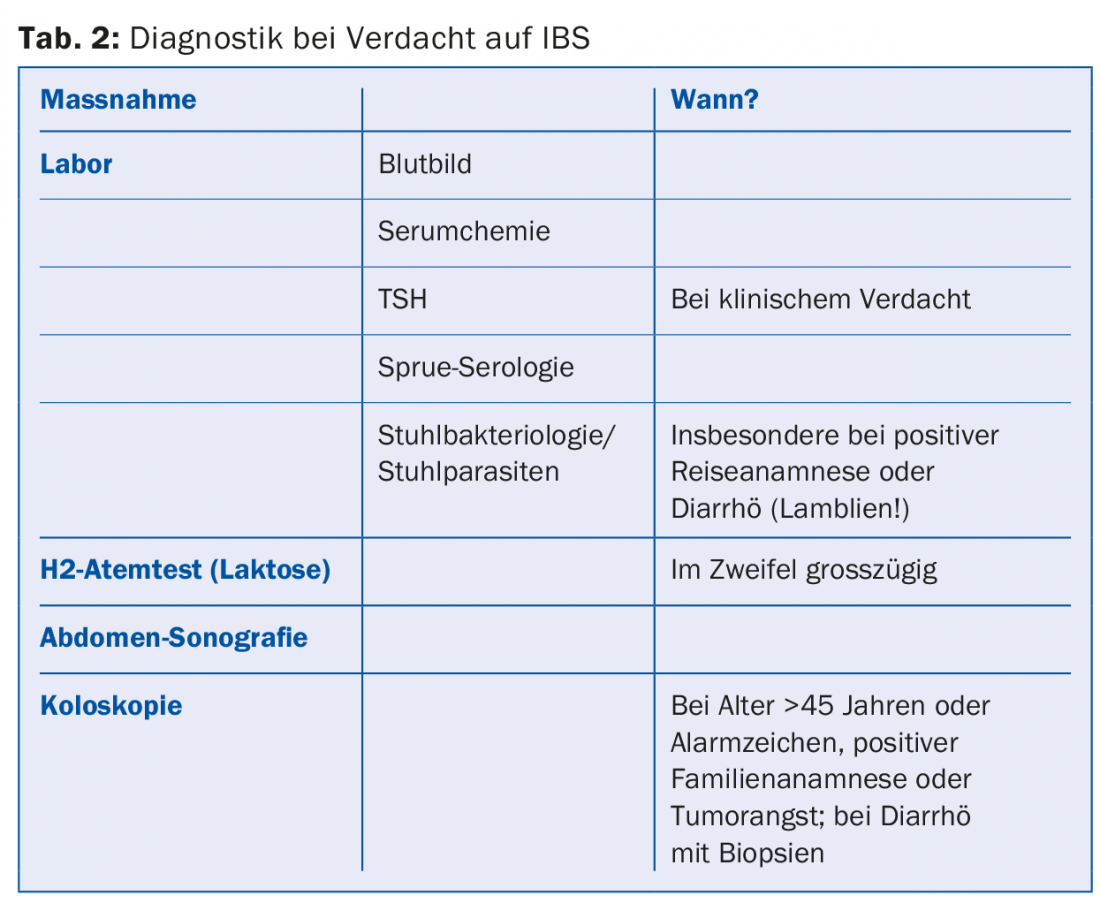

The diagnosis is based on the recognition of the typical clinical symptom pattern in the absence of alarm signs (Tab. 1) and unremarkable physical examination findings as well as the individualized differential diagnostic exclusion of relevant organic diseases. Specific tests that allow a clear differentiation from other diseases are lacking. The diagnosis should be made as initially as possible, with the least possible expenditure of equipment and money [3,4].

The typically unremarkable basic laboratory (blood count with ESR/CRP, clinical chemistry, TSH) should be supplemented by the determination of the sprue serology (antigliadin and antiendomysium antibodies as well as antibodies against tissue transglutaminase [IgG, IgA] and determination of total IgA) in the sense of the intended thorough initial diagnosis, since celiac disease can manifest itself with practically the same symptoms as IBS [4]. IBS patients are approximately five times more likely to have a pretest diagnosis of sprue than the normal population [5]. According to a recent meta-analysis, Sprue patients have a 5.6-fold increased risk of IBS symptoms, and 38% clinically present with full-blown IBS [6]. Therefore, almost one third of all Sprue patients (28%) are initially mistakenly treated for IBS, in quite a few cases even for several years [7].

Especially in patients with a positive travel history or diarrhea, stool examinations for bacteria, parasites (lamblia!) and leukocytes as well as calprotectin (to differentiate chronic inflammatory bowel disease) should also be performed [8,9]. Calprotectin is a calcium-binding protein that is not degraded by intestinal bacteria and is mainly derived from neutrophil granulocytes when they are released into the intestinal lumen during intestinal inflammation. Calprotectin is therefore suitable for differentiating inflammatory diseases from functional diseases such as irritable colon, but does not allow differentiation between infectious and non-infectious inflammation. It may also be elevated in gastrointestinal bleeding or tumors, as well as diverticulitis or liver cirrhosis.

In case of clinical indications for lactose intolerance, such as anamnestically indicated intolerance of dairy products or pronounced flatulence, this should be searched for by means of an H2 breath test or genetic tests or excluded by means of an omission test lasting several weeks. However, coincidence of both diseases is also possible.

In most cases, abdominal ultrasonography is also performed initially, but this usually does not reveal any serious pathologic findings. In approximately 5% of patients, gallstones are discovered, which may be the reason for an inadequate surgical indication if the IBS symptoms are misinterpreted as symptomatic cholecystolithiasis (Table 2).

A decision on whether to perform ileocolonoscopy must be made on a case-by-case basis. It is indicated in all patients over 50 years of age for polyp screening or early cancer detection alone and should always be performed in patients with alarm signs (Table 1). Ileocolonoscopy is necessary to confirm the diagnosis in that it is of high value for the detection or exclusion of relevant differential diagnoses (inflammatory bowel disease, diverticulitis, infectious or microscopic colitis), but it need not be performed in cases of unremarkable baseline diagnosis and younger patients without alarm signs. Nevertheless, the examination may also be necessary in this group in the sense of “reassurance” to be used therapeutically, in order to be able to convincingly convey the harmlessness of the complaints to the patients.

“Reassurance” and lifestyle

For the treatment of IBS, general measures should be exhausted before the use of drug therapy. A very high value is placed on “reassurance”, i.e. reassuring and informing the patient that the symptoms are harmless and that the prognosis is good with a normal life expectancy. For example, one study showed that the diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome did not need to be revised even over a follow-up period of 30 years, i.e., no carcinomas or other severe chronic or inflammatory diseases were missed. Repeated and superfluous diagnostics should therefore be avoided as far as possible. Personal attention in the context of doctor-patient interaction, as well as attendance at self-help groups, the natural course of the disease, and the placebo effect, can contribute to symptom relief and a reduction in visits to the doctor.

There are no general lifestyle or dietary recommendations. However, individual trigger factors that may aggravate the symptoms (stress, lack of sleep, nicotine/alcohol consumption, certain foods, lack of exercise, etc.) should be identified and avoided.

Nutrition and probiotics

In patients with constipation (IBS-C), a high-fiber diet is recommended, with assistance from bulking agents if necessary. However, highly flatulent foods (cabbage, beans, onions, etc.) and especially bran-containing dietary fiber should be avoided, as these often exacerbate abdominal pain symptoms [4,8,10].

The so-called FODMAP diet also aims to avoid flatulent food components. FODMAP stands for fermentable short-chain carbohydrates resp. Oligo-, di- and monosaccharides and polyols (“fermentable oligo-, di- and monosaccharides and polyols”). FODMAPs include fructose, lactose, and sugar alcohols such as sorbitol and xylitol. These osmotically highly active substances are poorly absorbed in the intestinal lumen, but are bacterially fermented with gas formation (hydrogen, methane), which leads to flatulence and intestinal distention and thus to pain. Several studies have shown significant improvement in IBS symptoms on a low FODMAP diet. However, such a change in diet should only be made with the support of a trained nutritionist in order to avoid excessive restriction and even malnutritive diets.

The administration of probiotics (Aktifit®, Actimel®, LC1®, Activia®, Perenterol®, VSL#3®) can attempt to influence the microbiome, which is often altered in IBS, in terms of health benefits. Here, preparations of individual strains or mixtures of Lactobacilli, Bifidobacteria or Saccharomyces are used, mostly in fermented milk or in yogurts (cave FODMAP!). The effect is preparation-specific and dose-dependent. Which preparations should be used in which patients and which IBS subtype remains unclear. In the absence of a response, a change of preparation should be made [11]. The therapy is designed as a long-term therapy and has few side effects.

Drug treatment: general aspects

The type of drug therapy is based on the predominant IBS subtype and is primarily probationary in nature. If the response is insufficient, the medication should be stopped after three months at the latest or supplemented by therapy alternatives. In general, one should be aware that there is only weak evidence overall for the efficacy of drugs in IBS; the placebo response rate is around 50% in double-blind studies, and the therapeutic gain of verum is in the order of only 15-20%.

Stool Regulators

Stool regulators such as psyllium husks (Metamucil®) or Sterculiae gummi (Normacol®, Colosan mite®) are first-line medications, especially in the treatment of IBS-C. There is evidence of benefit especially from psyllium husk-containing preparations for constipation and pain [10]. In addition, there is evidence that they also have a beneficial effect in the diarrhea subtype by increasing stool consistency. However, patients must be informed that the occurrence or worsening of flatulence may also occur under the mentioned medications. Osmotic laxatives of the macrogol type (Transipeg forte®, Movicol® sachets) are used when satisfactory improvement of constipation cannot be achieved with stool-regulating substances.

The beneficial effect of loperamide (Imodium®) in diarrhea subtype IBS has been demonstrated in several prospective randomized trials, with improvements in both stool consistency and imperative bowel movements. However, increased nocturnal abdominal discomfort occurred in some cases, possibly in the context of drug-induced constipation. The application of loperamide syrup, which can be dosed and titrated more precisely until the desired effect is achieved, is particularly recommended.

Pain therapy

Analgesics such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), metamizole, or acetaminophen have no place in the treatment of IBS due to lack of efficacy. Opiates are also not recommended due to lack of data and are also known to have an obstipating effect.

The spasmolytic drug mebeverine (Duspatalin® retard) showed a therapeutic gain of 22 percentage points with respect to pain compared to placebo [10]. This corresponds to an NNT (“number needed to treat”) of 5, so that this preparation can be used primarily for the treatment of pain (IBS-A/IBS-M).

Phytotherapeutics

With Iberogast®, a mixture of nine different herbal extracts (peppermint, chamomile, lemon balm, caraway, celandine, milk thistle, licorice root, angelica and farmer’s mustard), a scientifically well-studied phytotherapeutic is also available for the treatment of functional gastrointestinal disorders (functional dyspepsia and IBS). In a meta-analysis of four studies, a 19% reduction in severe and very severe IBS symptoms was achieved compared to placebo, corresponding to an NNT of 5, regardless of IBS subtype [12].

Peppermint oil alone is available in capsule form (Colpermin®) and, according to a meta-analysis of four studies, leads to a reduction in persistent complaints from 65 to 26%, corresponding to a relative risk of 0.43 [10].

Antidepressants

Tricyclic antidepressants (e.g., amitriptyline 10 mg, Tryptizol®) and serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) have a beneficial effect on IBS symptoms, regardless of subtype. In meta-analyses, the relative risk for persistent discomfort was 0.68 and 0.62, respectively, corresponding to a therapeutic gain over placebo of about 33% and an NNT of 3-4, although very few studies separately assessed the pain component [13]. Side effects of amitriptyline include urinary retention and constipation, which can be problematic in IBS-C. In addition, non-retarded amitriptyline 10 mg (tryptizole) is available in Switzerland only via import from the EU.

Linaclotide (Constella®)

A newer generation drug for the treatment of moderate-to-severe IBS-C in adults is linaclotide (Constella®). It increases the local cGMP concentration in the intestinal mucosa by direct activation of luminal guanylate cyclase C (GC-C), which leads to activation of a chloride ion channel and thus to secretion of chloride, bicarbonate and water into the intestinal lumen. This mechanism of action corresponds to the pathomechanism of secretory diarrhea (“traveler’s diarrhea”) triggered by bacterial toxins, in which activation of GC-C also occurs due to the heat-stable E. coli. enterotoxin. In addition, the drug also has a direct analgesic effect by inhibiting afferent visceral nerve fibers. The dosage for IBS-C is 290 μg/d, to be taken 30 minutes before the first main meal.

In the pivotal study of 800 patients, there was improvement in both abdominal pain (55 vs. 42%) and IBS symptoms (37 vs. 19%), corresponding to an NNT of 8 [14]. Initial improvements begin after just one week of treatment and then continue throughout the treatment period. Linaclotide was shown not to cause a rebound effect when treatment was stopped after three months of continuous treatment. A very common side effect is markedly watery, secretory diarrhea in about 16% of patients, leading to discontinuation of therapy in about 4% of patients. In addition, long-term side effect data are not yet available. Linaclotide is therefore considered a reserve drug for refractory cases; at 94 Swiss francs for four weeks, the price is significantly higher than that of the other drugs.

Rifaximin (Xifaxan®)

With the expected approval of rifaximin (Xifaxan®) for the treatment of hepatic encephalopathy, a synthetic, oral, non-absorbable broad-spectrum antibiotic for influencing the microbiome will probably also be available in Switzerland in the near future, which can also be used off-label in (non-IBS-C) IBS. It has already been approved in the EU for the treatment of enteral infections and travelers’ diarrhea and in the U.S. for intestinal decontamination in hepatic encephalopathy, and has also been used in studies to modify the microbiome in irritable bowel syndrome. Presumably by reducing bacterial fermentation and harmful bacterial metabolites or by altering the immune response to the gut microbiome, improvement in IBS symptoms and specifically bloating was described in approximately 42% of patients (vs. 32% on placebo) [15]. However, the therapeutic gain compared to placebo is only 10%, which is at the limit of clinical relevance, and this with expected therapy costs of 450 euros for a 14-day treatment.

The risk of resistance development is judged to be low based on the data available to date over only relatively short observation periods. Although some patients who are otherwise difficult to treat or considered refractory to therapy will certainly benefit, broad and unselective antibiotic therapy of a chronic, nonfatal disease with a high prevalence nevertheless remains questionable because of potential resistance developments and unclear long-term effects. Especially because there are other ways to influence the microbiome, such as dietary measures like reduction of FODMAP, administration of probiotics or even microbiome transfer (“stool transplantation”). In addition, gastrointestinal side effects may also occur with rifaximin.

Literature:

- Longstreth GF, et al: Gastroenterology 2006; 130(5): 1480-1491.

- Wong RK, et al: Am J Gastroenterol 2010; 105(10): 2228-2234.

- Chang L, et al: Gastroenterology 2014; 147(5): 1149-1472 e2.

- Layer P, et al: S3 guideline irritable bowel syndrome. Z Gastroenterol 2011; 49(2): 237-293.

- Cash BD, et al: Am J Gastroenterol 2002; 97(11): 2812-2819.

- Sainsbury A, et al: Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013; 11(4): 359-365 e1.

- Card TR, et al: Scand J Gastroenterol 2013; 48(7): 801-807.

- Spiller R, et al: Gut 2007; 56(12): 1770-1798.

- Tibble J, et al: Gut 2000; 47(4): 506-513.

- Ford AC, et al: BMJ 2008; 337: a2313.

- McKenzie YA, et al: J Hum Nutr Diet 2012; 25(3): 260-274.

- Madisch A, et al: Z Gastroenterol 2001; 39(7): 511-517.

- Ford AC, et al: Gut 2009; 58(3): 367-378.

- Rao S, et al: Am J Gastroenterol 2012; 107(11): 1714-1724; quiz p. 25.

- Menees SB, et al: Am J Gastroenterol 2012; 107(1): 28-35; quiz p. 6.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2015; 10(4): 10-15