If a patient suffers from obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), it predisposes him or her to a host of comorbidities, from cardiovascular to renal to pulmonary to neuropsychiatric. But there is also growing evidence for a reverse effect. Researchers from Ireland have examined the relationships between OSA and comorbidity, focusing on comorbidities that show evidence of a bidirectional relationship.

Possible mechanisms associated with OSA that contribute to comorbidity include intermittent hypoxia, fluctuating intrathoracic pressure, and recurrent microexcitations, which are integral features of obstructive apnea. Cellular or molecular consequences may include sympathetic excitation, systemic inflammation, and oxidative stress, in addition to metabolic and endothelial dysfunction, write Dr. Margaret Gleeson and Prof. Dr. Walter McNicholas of the School of Medicine, University College Dublin, and the Department of Respiratory and Sleep Medicine, St. Vincent’s Hospital Group, Dublin [1]. Different mechanisms may prevail for certain comorbidities.

Obesity

Approximately 70% of OSA patients are obese; conversely, 50% of individuals with a body mass index (BMI) >40 have OSA with an apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) >10. A higher BMI typically leads to more severe OSA, especially in men and in the younger population. Most research has focused on obesity as a risk factor for OSA, but evidence suggests that the relationship is bidirectional.

The accumulation of fat in the neck-neck area contributes to the narrowing of the oropharynx, resulting in an increased risk of upper airway collapse. In addition, abdominal obesity decreases upper airway traction, which further predisposes to collapse. In addition, intermittent hypoxia, which is a central feature of OSA, triggers a proinflammatory response in visceral adipose tissue and contributes to insulin resistance.

Therapeutic effects include severe weight loss, especially after bariatric surgery. In contrast, dietary intervention alone showed little effect over a 10-year follow-up period, the authors write. OSA patients with small preexisting maxillomandibular volume had the greatest benefit from weight loss, indicating an important interaction between upper airway anatomy and the effects of obesity.

Overweight men with OSA lose less weight in response to a one-year diet and exercise program than similarly overweight men without OSA. While continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy is highly effective in controlling OSA, paradoxically, some patients gain weight after starting CPAP treatment, particularly women and nonadipose patients. Overall, the relationship between obesity and OSA is synergistic in terms of cardiometabolic risk, with a variety of potential intermediate mechanisms, including inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, and insulin resistance, being amplified by the co-occurrence of both conditions, Dr. Gleeson and Prof. McNicholas state.

COPD

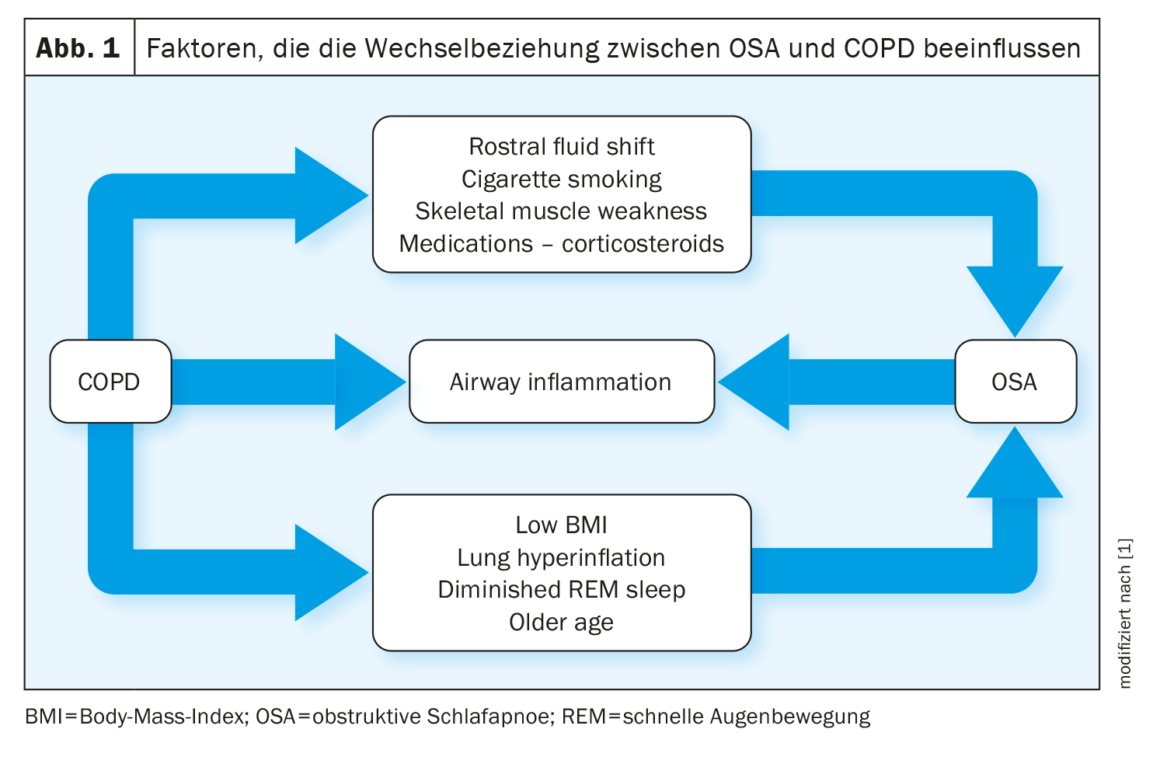

The relationship between COPD and OSA is described by the authors as “complex.” Some factors, such as pulmonary hyperinflation, protect against OSA, while others, such as fluid retention, promote OSA. Increasing BMI and smoking history correlate positively with the likelihood of OSA in patients with COPD (Fig. 1).

Work on OSA as a risk factor for COPD has yielded mixed results. For example, one study showed a higher prevalence of COPD and asthma in patients with OSA compared with a matched control population, particularly in women. OSA also appears to exacerbate lower airway inflammation in patients with COPD, and animal studies report that chronic intermittent hypoxia contributes to lung injury in mice by inducing inflammation and oxidative stress.

Patients with COPD-OSA overlap treated with long-term CPAP have similar survival to patients with COPD alone, whereas patients with overlap not treated with CPAP have higher mortality and rates of hospitalization with acute exacerbations. These findings underscore the importance of identifying coexisting OSA in patients with severe COPD so that optimal therapy can be selected, Dr. Gleeson and Prof. McNicholas said.

Diabetes

Diabetes and OSA often coexist, and there is increasing evidence of a bidirectional relationship.

Several cross-sectional cohort studies have shown an independent association with type 2 diabetes and insulin resistance; a pooled estimate of the relative risk for diabetes from nine original studies was 1.69 (95% CI 1.45-1.80). Mechanisms of diabetes and insulin resistance include intermittent hypoxia and sleep fragmentation leading to sympathetic arousal and inflammation. A cohort study of 8678 adults screened for OSA reported that individuals with severe OSA had a 30% higher risk of developing diabetes than those without OSA, after a mean follow-up of 67 months after controlling for confounding factors.

CPAP therapy alone for 24.5 weeks did not promote insulin sensitivity in nondiabetic patients with OSA, in contrast to weight reduction. Randomized control trials of CPAP in diabetic patients with OSA have yielded mixed results.

Some consequences of diabetes mellitus might predispose to OSA, including neuropathy affecting the muscles of the upper airway and disorders of respiratory control. A prospective study of nearly 300 000 health professionals found that OSA was an independent risk factor for new-onset diabetes, but conversely, insulin-dependent diabetes was an independent risk factor for OSA in women.

Hypertension

While hypertension is very common in patients with OSA, the vast majority of research on this topic has focused on OSA as a risk factor for hypertension.

Many population-based epidemiological studies clearly indicate that OSA is a risk factor for systemic hypertension, often with a nondescending nocturnal blood pressure (BP) profile. Data from the Sleep Heart Health Study showed a dose-dependent association with prevalent hypertension, and the Wisconsin Cohort Study reported a higher presence of hypertension associated with OSA after 4 years of follow-up. Data from the ESADA study involving 4372 patients with mild OSA found an independent association with prevalent hypertension, and a prospective study of 744 patients with mild/moderate OSA and normotensive baseline reported an association with new-onset hypertension at 9 years in patients <60 years.

There is limited evidence that hypertension may predispose to OSA. Data from studies in animals and small humans suggest that fluctuations in blood pressure may affect upper airway tone by showing inhibitory changes in the electromyogram (EMG). This is evidence that lowering blood pressure may improve airflow and reduce the severity of OSA.

Heart failure

The bidirectional relationship between sleep apnea and heart failure may be partially explained by common risk factors such as age, high BMI, and sedentary lifestyle. Unifying mechanisms, particularly fluid retention and redistribution, result in a bidirectional relationship in which it can be difficult to determine cause and effect.

OSA is associated with an increased risk of coronary heart disease occurrence and progression, congestive heart failure, and cardiovascular mortality. It may induce cardiac remodeling, contributing to heart failure, and may acutely impair cardiac function, exacerbating episodes of acute heart failure. Patients with a higher AHI have a higher degree of diastolic dysfunction. Patients without or with mild OSA had a 50% lower incidence of fatal events compared with patients with untreated moderate or severe disease. OSA can adversely affect the prognosis of heart failure and is associated with increased hospitalizations and post-discharge mortality in hospitalized OSA patients.

Treatment of OSA with CPAP improves intermediate cardiovascular endpoints such as blood pressure, heart rate and rhythm, and ejection fraction. One study found a 9% increase in left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) in addition to a daytime decrease in heart rate and blood pressure, which may reflect a reduction in nocturnal urinary excretion of epinephrine. However, while immediate physiologic improvement has been demonstrated with CPAP therapy, data demonstrating improved mortality and transplant-free survival are lacking for long-term efficacy.

In a randomized-controlled trial (RCT) of patients with severe OSA, sodium restriction and diuretic therapy resulted in only limited improvement in AHI, suggesting that fluid retention only partially explains the etiology of OSA in heart failure. In an acute exacerbation of hypertensive diastolic heart failure, diuretic therapy resulted in a reduction in body weight, increased pharyngeal caliber, and a decrease in AHI by 17. Conversely, in an observational study, diuretic therapy improved OSA in obese patients or patients with hypertension, but no significant improvement in OSA severity was observed in patients with heart failure.

Renal dysfunction

Current evidence suggests that kidney disease and sleep apnea have a bidirectional relationship. The prevalence of OSA is up to 10 times higher in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) than in the general population, but OSA remains under-recognized in CKD, explain the Irish researchers. The incidence of OSA increases proportionally to the severity of CKD, supporting its role in pathogenesis. One clinical trial reported a prevalence for OSA of 27%, 41%, and 57% in patients with eGFR >60, patients with eGFR <60 but without renal replacement therapy, and patients on hemodialysis, respectively.

Factors contributing to OSA in CKD include increased chemoreflex sensitivity, decreased clearance of uremic toxins, and hypervolemia. In a group of 40 hemodialysis patients, 70% had an AHI >15 and greater total body extracellular fluid volume, including neck, thoracic, and leg volumes, although there was no difference in BMI compared with those with an AHI <5.

Increased fluid overload predicts worsening OSA, and aggressive treatment of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) may reduce severity. Daily dialysis, nocturnal dialysis, and nocturnal automated peritoneal dialysis have been associated with benefits for OSA in observational studies related to reduced AHI, reduced respiratory congestion, and improved uremic clearance. Renal transplantation reverses many of the metabolic complications of ESRD and slows the progression of associated comorbidities, but its role in the benefit of OSA remains inconclusive.

While OSA may occur as a consequence of CKD, there is evidence that it may also contribute to CKD and progressive decline in GFR. OSA has also been associated with higher morbidity and mortality in patients with ESRD, which may be related to the compounding effects of comorbidities such as cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease, including arrhythmias, coronary disease, and stroke.

OSA-induced renal disease can be explained by two primary mechanisms: Hypertension and intrarenal hypoxia with glomerular hyperfiltration. The renal medulla is particularly sensitive to hypoxia, triggering oxidative stress, systemic inflammation, and endothelial dysfunction, leading to tubulointerstitial injury, the hallmark of CKD. Apneic episodes stimulate the sympathetic nervous system and RAAS system, leading to systemic and glomerular hypertension, vascular damage, and arterial wall stiffness, culminating in renal ischemia.

In one study, CPAP therapy positively affected renal hemodynamics in patients with normal renal function at baseline, suggesting a benefit in slowing renal injury. However, the role of CPAP in attenuating the progression of renal dysfunction in OSA is uncertain, with few studies focusing on patients with existing CKD.

Stroke

Sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) is common in patients after stroke. Whether OSA is a provoking factor, potentiating known vascular risk factors such as hypertension, or a consequence of stroke-related brain injury remains unclear.

OSA is a risk factor for stroke and results in approximately a two-fold increase in stroke incidence. A meta-analysis identified an increased incidence of stroke in patients with untreated OSA, even after accounting for potential confounders such as age, BMI, diabetes, and high blood pressure. Observational studies indicate a reduction in the risk of stroke in patients with OSA on CPAP, especially in patients compliant with therapy. RCTs suggested that compliance of >4 h with treatment might provide some benefit.

The prevalence of OSA is high in stroke, with one-third of survivors documenting an AHI >30, although it is possible that stroke may reveal preexisting OSA. Sleep architecture after stroke can affect respiratory control mechanisms at the central level, but in particular, stroke can impair upper airway muscle function, increasing collapsibility.

Depression

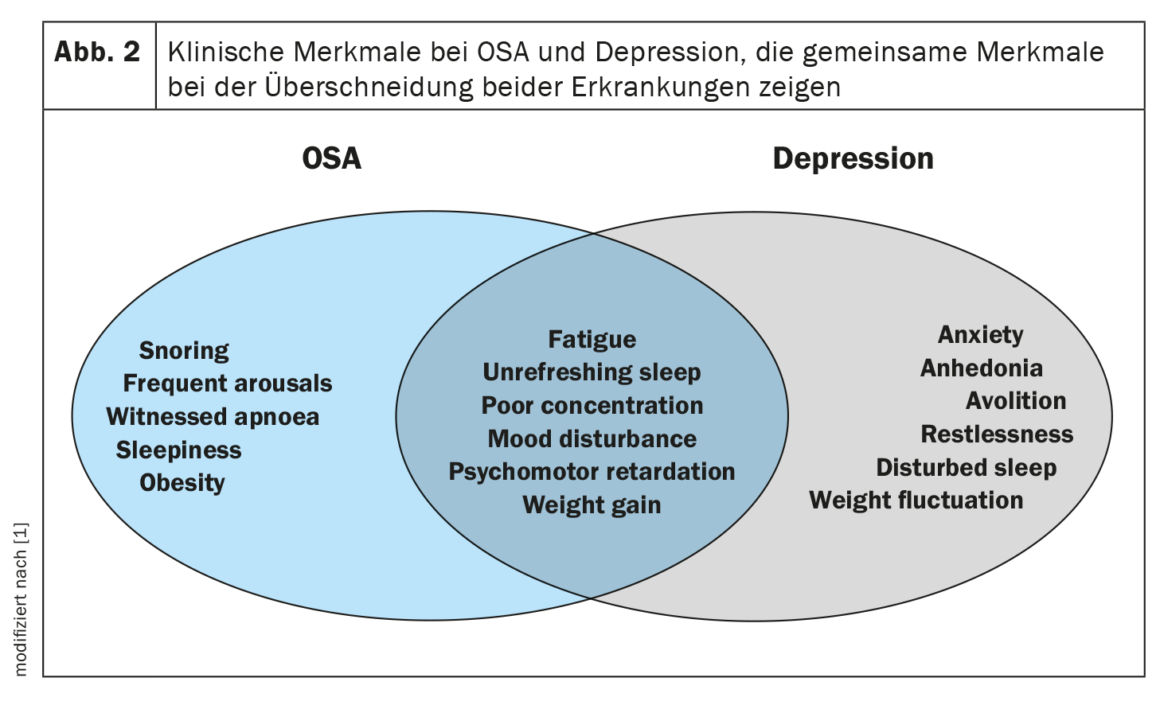

Depression and OSA may share similar symptoms, including poor concentration, memory impairment, and fatigue, which complicate their clinical assessment and diagnosis (Fig. 2). Sleep disturbance is a common self-reported symptom of depression and may be a predictive symptom for the subsequent development of depression. A recent theory suggests that people with depression have a higher risk of OSA later in life. Expected mechanisms underlying each process include sleep fragmentation, frequent awakenings, and intermittent hypoxic episodes leading to cerebral hypoperfusion and neurotransmitter dysfunction. Despite biological plausibility, there has been little research on possible bidirectional relationships, and results have been inconsistent.

In clinical cohorts, the prevalence of depression in OSA ranges from 20-40%, and there appears to be an increased odds ratio for depression with increasing severity of SDB. However, other smaller studies reported that the presence or severity of OSA were not independent predictors of depression scores or subsequent hospitalizations.

Treatment of OSA with CPAP for 5 or more hours per night for at least 3 months improved depressive symptoms, including suicidal ideation, independent of antidepressant use.

Conversely, depression has not been well studied as a possible cause of OSA. Prevalence reports indicate that 15% of psychiatric inpatients with major depressive disorder (MDD) have an elevated AHI on overnight polysomnography, and 18% of patients with MDD also meet diagnostic criteria for OSA.

A review of prospective trials of five different antidepressants found that only two had a positive effect on reducing AHI but no effect on sleepiness or sleep quality. In addition, undiagnosed OSA may worsen with some pharmacologic treatments that target depression, with weight gain being a possible factor. Benzodiazepines may increase the frequency and duration of apneic events by affecting upper airway tone and arousal threshold.

Literature:

- Gleeson M, McNicholas WT: Bidirectional relationships of comorbidity with obstructive sleep apnea. Eur Respir Rev 2022; 31: 210256; doi: 10.1183/16000617.0256-2021.

InFo PNEUMOLOGY & ALLERGOLOGY 2023; 5(1): 24-25.