In the acute stage of viral hepatitis, the clinical picture is similar for all five pathogens. HBV and HCV infections are the most dangerous chronic infectious diseases worldwide. In contrast to hepatitis A and E, hepatitis B and C predispose to chronic hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma. In this country, a vaccination is available against hepatitis A and B. There is currently no vaccine available in Europe against HCV, HDV and HEV. Hepatitis C can now be cured with antiviral medication in over 95 percent of cases.

Classical viral hepatitis is an inflammation of the liver caused by the hepatitis viruses A, B, C, D and E.

In the European region of the World Health Organization (WHO), around 100,000 deaths per year are attributable to viral hepatitis [1].

The exclusively human pathogenic hepatitis A virus (HAV) usually only induces acute hepatitis and is primarily found in developing countries.

Hepatitis E virus (HEV) has a similar epidemiology, but is also widespread in industrialized countries and can also induce chronic disease.

Chronicity can also occur with the hepatitis B virus (HBV), which is widespread worldwide and whose satellite virus hepatitis D (HDV) additionally increases the carcinogenic potential.

The hepatitis C virus (HCV), which is also widespread worldwide, carries a high risk of chronification and is also associated with a high carcinogenic potential [2].

“Liver cancer is the third leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide, and the most important modifiable risk factors for primary liver cancer are infections with the hepatitis B or C virus. However, there is a huge stigma attached to hepatitis and this needs to be tackled at local and national levels and across the European Region. This stigma often discourages people from seeking timely testing, treatment and support, perpetuating the cycle of infection and undermining public health efforts in sexual and reproductive health, antenatal care, viral hepatitis testing and treatment, and screening for liver cancer,” said Dr Hans Henri Kluge, WHO Regional Director for Europe [18].

Some manifestations of acute hepatitis are virus-specific, but usually go through the following phases [3]:

- Incubation period: The virus multiplies and spreads without causing symptoms.

- Prodromal or pre-icteric phase: non-specific symptoms such as loss of appetite, feeling ill, nausea and vomiting; a newly developed aversion to cigarettes (in smokers); often fever or pain in the right upper abdomen; urticaria and arthralgia often occur, particularly with HBV infection.

- Icteric phase: After 3-10 days, the urine becomes darker, followed by jaundice. The systemic symptoms usually subside and the patient feels better, although the jaundice increases. The liver is usually enlarged and painful to the touch, the edges of the liver remain soft and smooth. Minor splenomegaly occurs in 15-20% of patients.

- Recovery phase: During this 2-4 week period, the symptoms of jaundice subside. Spontaneous recovery from acute viral hepatitis occurs in the majority of patients within 4-8 weeks after the onset of symptoms.

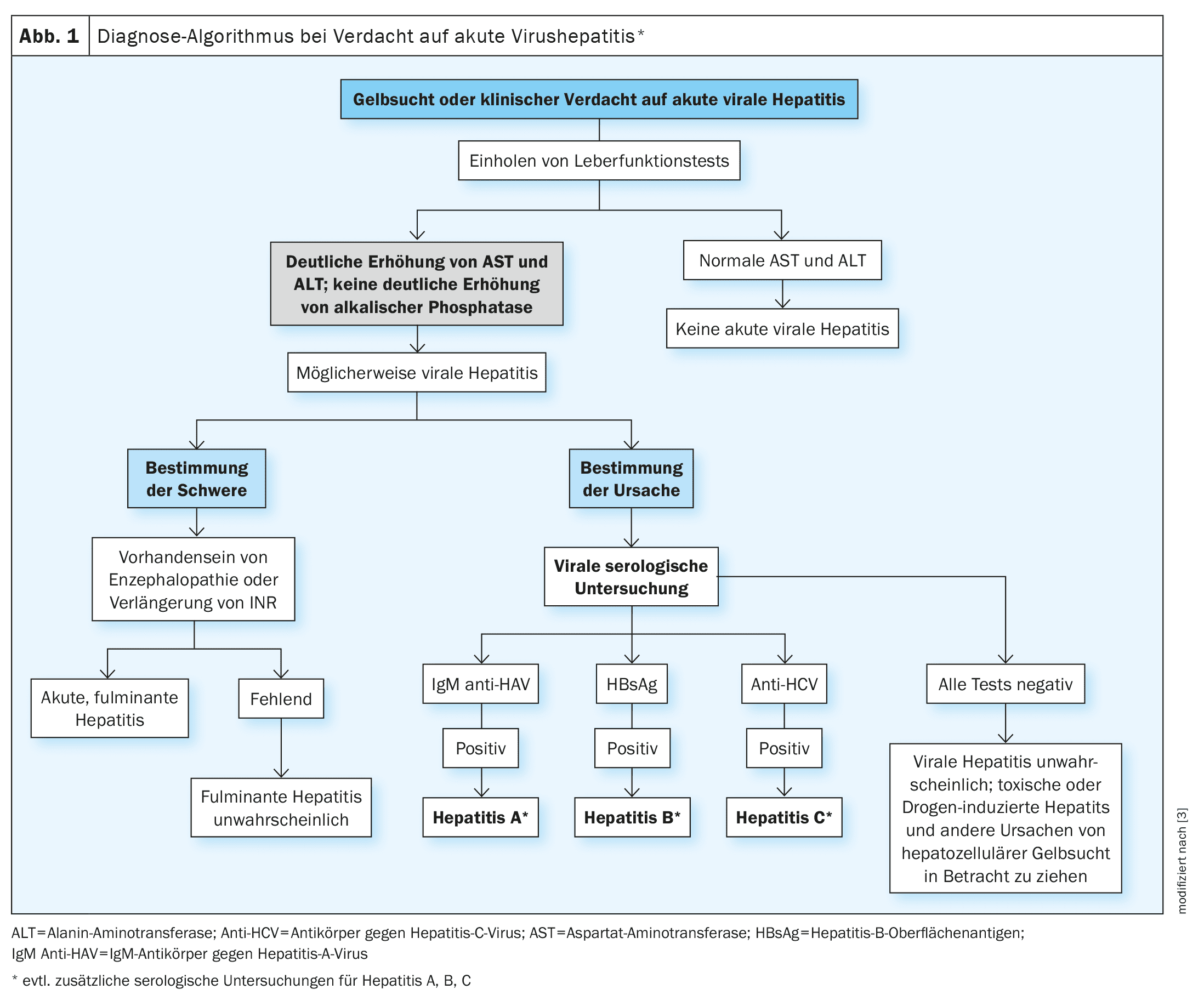

A simplified diagnostic algorithm for patients with suspected acute viral hepatitis is shown in Figure 1 [3].

HBV: HDV co-infection increases the risk of severe progression

HBV is predominantly endemic in developing countries (e.g. South East Asia, Africa and South America) with virus carrier rates of 5-10%. In addition to geographical distribution, the prevalence rate of HBV also depends on risk behavior [4]. HBV is transmitted through contact with the blood of an infected person (e.g. toothbrush, razor, needlestick injury) or sexual contact with a person suffering from hepatitis B.

Course: The clinical course is highly variable and ranges from asymptomatic and inapparent to fulminant and severe liver inflammation.

In 90% of cases, an acute hepatitis B infection heals on its own [5].

Depending on age, immune status and other factors (e.g. virus mutants), HBV infection progresses to a chronic form in around 10% of acute cases

An acute or chronic HBV infection can be accompanied by an HDV infection, which is referred to as a simultaneous or superinfection.

The so-called satellite virus HDV only replicates in the presence of HBV [2].

The virus was first described as an HBV-associated antigen (“delta agent”) in 1977.

Around 5% of chronically HBV-infected patients worldwide are co-infected with HDV

HDV co-infection greatly increases the risk of fulminant hepatitis. While HDV simultaneous infection can be eliminated in 95% of cases, superinfection of an HBV carrier with HDV leads to a chronic course in 80% of infected individuals [2]. This increases the probability of developing liver fibrosis or cirrhosis tenfold and triples the risk of developing HCC [8]. The HDV transmission route corresponds to that of HBV.

Treatment: There are no specific drugs for the treatment of acute hepatitis B. However, chronic hepatitis B can be treated with antiviral drugs or with pegylated interferon- α [5]. The HBV viral load can be reduced with the available antiviral therapies. As HBV cannot be eliminated from the body, treatment to prevent viral replication must often be maintained for life [9]. Patients with liver cirrhosis or permanently increased inflammatory activity have an increased risk of developing HCC and should be monitored accordingly. Pegylated interferon-α is sometimes used to treat HDV, although this is an off-label therapy [9]. The first and only drug treatment option for HDV that has recently been approved in Switzerland is bulevirtide (Hepcludex®) [20]. Bulevirtide blocks the entry of HB and HD viruses into hepatocytes by binding to and inactivating NTCP – a bile salt liver transporter that serves as an essential HBV/HDV entry receptor.

Vaccination: The vaccination protects against HBV infection and also offers reliable protection against HDV.

In Switzerland, the Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH) recommends vaccination for 11 to 15-year-olds as part of basic immunization.

The vaccination can be repeated in adulthood.

If possible, children of HBV-positive mothers should receive the first vaccination dose immediately after birth

Hepatitis C is well treatable today

HCV, together with HBV, is one of the main causes of acute and chronic liver disease worldwide [2].

Course: Acute HCV infections are usually asymptomatic or with flu-like symptoms, which heal themselves in around 15% of patients.

In 60-85% of cases of HCV infection, chronic hepatitis C develops. HCV-induced immunopathogenesis leads to a reduction in liver regeneration, which, if left untreated, results in the development of liver fibrosis/cirrhosis

Therapy: HCV infection can now be cured by the use of direct-acting antiviral agents (DAA).

Since DAAs have become available, interferon-based therapy has become superfluous [15].

The main aim of treating a chronic HCV infection is to eradicate the HCV.

Cure of viral infection, in terms of sustained virologic response, is defined as the absence of viral detection in the blood 12 weeks after initiation of anti-HCV therapy.

Patients who reach this endpoint have an approximately 99% chance of maintaining cure

Hepatitis A leads to acute hepatitis more frequently than HEV

HAV and HEV are generally classified as self-limiting, acute hepatitis. Around 30% of <6-year-old children and 70% of adults develop acute hepatitis A. Symptomatic hepatitis E occurs in only 5% of all transmissions [2].

Progression: In around 10-20% of cases of acute, self-limiting hepatitis A, a relapse occurs during the course of the disease.

Acute liver failure is a very rare complication of an HAV infection (approx. 0.5-1% of symptomatic cases), whereby older multimorbid people are particularly affected

Therapy: Currently, there are only supportive treatment options for acute HAV infection; antiviral therapy is not yet available.

Patients with persistent nausea or vomiting and patients who show signs of liver failure should be admitted and closely monitored

Literature:

- Inselspital Bern: Viral hepatitis, www.leberzentrum-bern.ch/de/medizinisches-angebot-leber-gallenblase/lebererkrankungen/virale-hepatitis.html,(last accessed 24.07.2024).

- Bender D, Glitscher M, Hildt E: Viral hepatitis A to E: Prevalence, pathogen characteristics and pathogenesis Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 2022; 65(2): 139-148.

- “Overview of Acute Viral Hepatitis,” Sonal Kumar, MD, MPH, Weill Cornell Medical College, Reviewed/revised Aug. 2022, www.msdmanuals.com,(last accessed 7/24/2024).

- Robert Koch Institute (RKI): Laboratory for hepatitis virus infections, www.rki.de/DE/Content/Institut/OrgEinheiten/Abt1/FG15/Labor_Hepatitisvirus.html,(last accessed 24.07.2024).

- “Hepatitis behandeln”, Hepatitis Switzerland, https://hepatitis-schweiz.ch/testen-und-behandeln/behandeln,(last accessed 24.07.2024).

- WHO: Global hepatitis report, 2020.

- Zhang Z, Urban S: Interplay between Hepatitis D Virus and the Interferon Response. Viruses. 2020 Nov 20; 12(11): 1334.

- Turon-Lagot V, et al: Targeting the Host for New Therapeutic Perspectives in Hepatitis D. J Clin Med 2020 Jan 14; 9(1): 222.

- University Hospital Zurich (USZ): Viral hepatitis therapy, www.usz.ch/fachbereich/gastroenterologie-und-hepatologie/angebot/virushepatitis-therapie,(last accessed 24.07.2024).

- “Hepatitis B”, Amt für Gesundheit, Basel Landschaft, www.baselland.ch,(last accessed 24.07.2024).

- Bender D, Hildt E: Effect of Hepatitis Viruses on the Nrf2/Keap1-Signaling Pathway and Its Impact on Viral Replication and Pathogenesis. Int J Mol Sci 2019 Sep 19; 20(18): 4659.

- Robert Koch Institute: Epidemiological Bulletin, 2021.

- Mehta P, Grant LM, Reddivari AKR: Viral Hepatitis. [Updated 2024 Mar 10]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554549,(last accessed 24.07.2024).

- Simmons B, et al: Risk of Late Relapse or Reinfection With Hepatitis C Virus After Achieving a Sustained Virological Response: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis 2016; 62(6): 683-694.

- Shin EC, Jeong SH: Natural History, Clinical Manifestations, and Pathogenesis of Hepatitis A. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2018 Sep 4; 8(9): a031708.

- Lhomme S, et al: Hepatitis E Pathogenesis. Viruses. 2016 Aug 5; 8(8): 212.

- Koenig KL, Shastry S, Burns MJ: Hepatitis A Virus: Essential Knowledge and a Novel Identify-Isolate-Inform Tool for Frontline Healthcare Providers. West J Emerg Med 2017; 18(6): 1000-1007.

- World Health Organization: World Hepatitis Day, www.who.int/europe/de/news/item/28-07-2023-world-hepatitis-day–reducing-the-risk-of-liver-cancer,(last accessed 24.07.2024).

- “Hepatitis B”, www.infovac.ch/de/impfunge/nach-krankheiten-geordnet/hepatitis-b,(last accessed 24.07.2024).

- Swissmedic: Medicinal product information, www.swissmedicinfo.ch,(last accessed 25.09.2024)

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2024; 19(8): 18–21