Infection of the gastric mucosa with the Helicobacter bacterium leads to gastric inflammation and also increases the risk of stomach cancer. A research team from Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin and the Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in the Helmholtz Association (MDC) has now been able to elucidate characteristic changes in the gastric glands in the course of infection. The scientists have found a previously unknown mechanism that limits cell division in healthy tissue and thus protects against cancer development. However, a stomach infection cancels this out, allowing cells to grow uncontrollably.

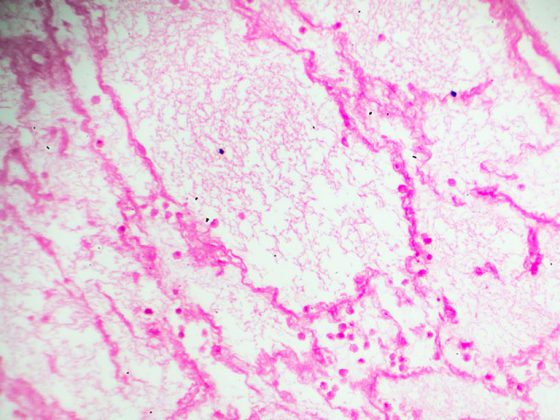

Colonization of the stomach with Helicobacter pylori occurs in about half of humanity worldwide. This makes it one of the most common chronic bacterial infections. As a result, inflammation of the stomach or stomach cancer may develop. Due to constant contact with gastric acid, the healthy gastric mucosa completely renews itself within a few weeks, while its structure and composition always remain unchanged. “Until now, it was assumed that Helicobacter infection directly damages the glandular cells of the gastric mucosa,” explains Prof. Dr. Michael Sigal, Emmy Noether research group leader at the Charité Medical Clinic with a focus on hepatology and gastroenterology and at the Berlin Institute for Medical Systems Biology (BIMSB), which is part of the Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in the Helmholtz Association (MDC). “Our team has now found that the complex interactions of various cells and signals that provide tissue stability are disrupted by infection.”

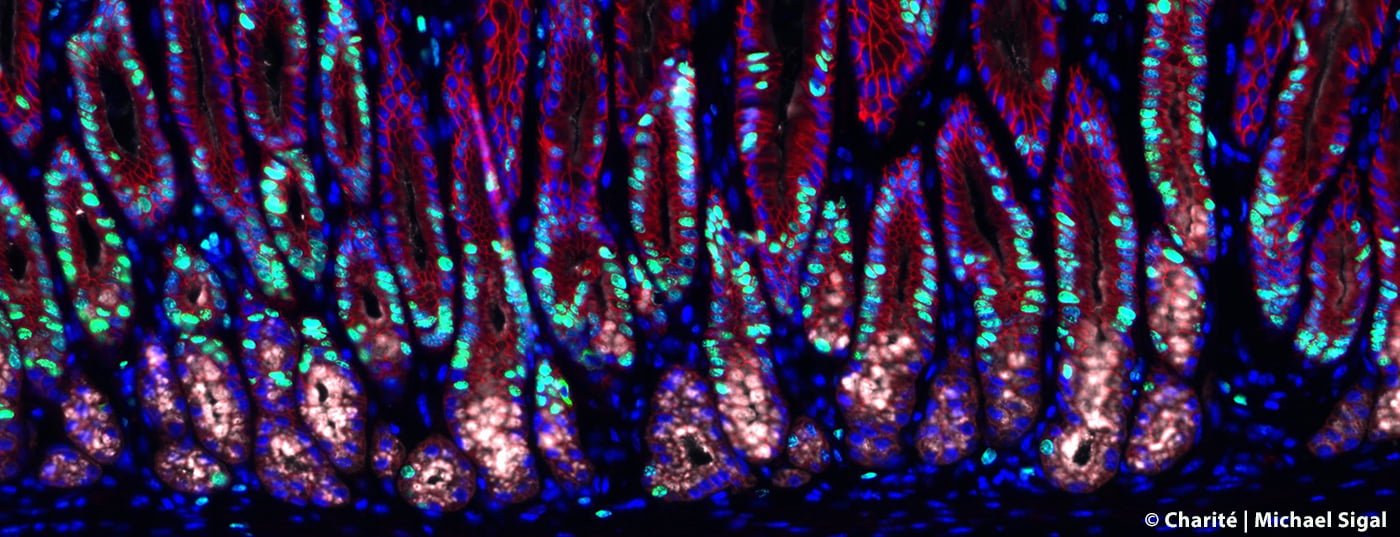

To track the changes in the gastric glands caused by Helicobacter infection, the research team, together with scientists at the Max Planck Institute for Infection Biology, has made use of complex mouse models in which specific cells of the gastric glands can be visualized, isolated and studied in detail using state-of-the-art technologies – such as imaging and single-cell sequencing on tissue. In addition, they developed special organ-like microstructures – so-called organoids – in the laboratory in order to be able to limit the use of animal models. With the help of these tiny miniature stomachs, they were able to recreate many of the glands’ properties and study the influence of multiple signals on the stem cells there, which can give rise to different cell types.

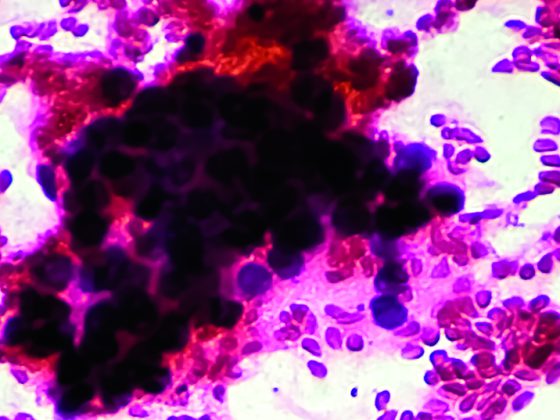

“We have discovered that the so-called stromal cells surrounding the glands are not – as previously thought – only responsible for mechanical stability. They also produce messenger substances that have a significant influence on the behavior of the glands,” describes Prof. Sigal. These messenger substances also include the “Bone Morphogenetic Protein” (BMP), which is important for tissue development. The researchers were able to show that stromal cells surrounding the base of the gland continuously suppress the BMP signaling pathway, stimulating the division of stem cells there. In contrast, stromal cells at the tip of the gland activate the signaling pathway and thus prevent cell division there. This influence of the environment is the basis for the stable gland structure. Helicobacter infection results in the release of end-inflammatory substances such as interferon-gamma (IFN-γ). In the course of this inflammatory reaction, increased messenger substances are now produced that stimulate cell division of the stem cells in the glands. This eventually leads to what is known as hyperplasia – that is, the tissue enlarges and precancerous lesions can develop.

“Our findings show that infection and associated inflammation have many more effects in tissues than previously thought: classical inflammatory substances such as IFN-γ not only have a direct antimicrobial effect, but also influence cell division and stem cell behavior in tissues. In the case of tissue damage, rapid cell division can be very useful to enable rapid healing. However, in the case of chronic inflammation in the course of a Helicobacter infection, it could promote the development of cancer precursors,” summarizes Prof. Sigal. The signaling pathways in the interaction between the immune system and stem cells, which could also be significant for organs other than the stomach, thus represent a starting point for new therapies – both in cancer prevention and in regenerative medicine.

Original source:

Kapalczynska M, et al: Schmidt F, et al: BMP feed-forward loop promotes terminal differentiation in gastric glands and is interrupted by H. pylori-driven inflammation. Nature Communication 2022; doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-29176-w.