Complex systems of care put patients at risk. Patient safety in oncology can be enhanced through standardization of processes, technological solutions and a consolidated safety culture.

The life expectancy of cancer patients has increased significantly in recent decades thanks to advances in therapy. For example, in England, the 10-year survival rate across all cancers doubled from 24% to 50% between 1971 and 2011 [1]. This is an outstanding success. However, as treatment options improved, medical therapies became more elaborate, the number of drugs and routes of administration increased, and the timing of therapies, their regimens, and dose calculations became more complex. With this variability, the risk for errors in care has increased. For example, the risk of prescribing errors increases significantly if body surface area and renal function must be considered in the dose calculation [2].

In addition, organizing patient care has become much more difficult. There are frequent inter- and intrasectoral changes of patients, new specializations, strong fragmentation and division of labor, and resulting complicated processes. The use of new technologies also leads to more complexity. All these factors lead to an increase in interfaces, communication and interaction.

However, the general conditions under which oncology care takes place (such as, in particular, the working environment of the professional staff) often lag behind medical progress. Information breakdowns occur (e.g. between outpatient clinic and ward, between physicians and nursing, between prescription and production) due to incompatible EDP systems.

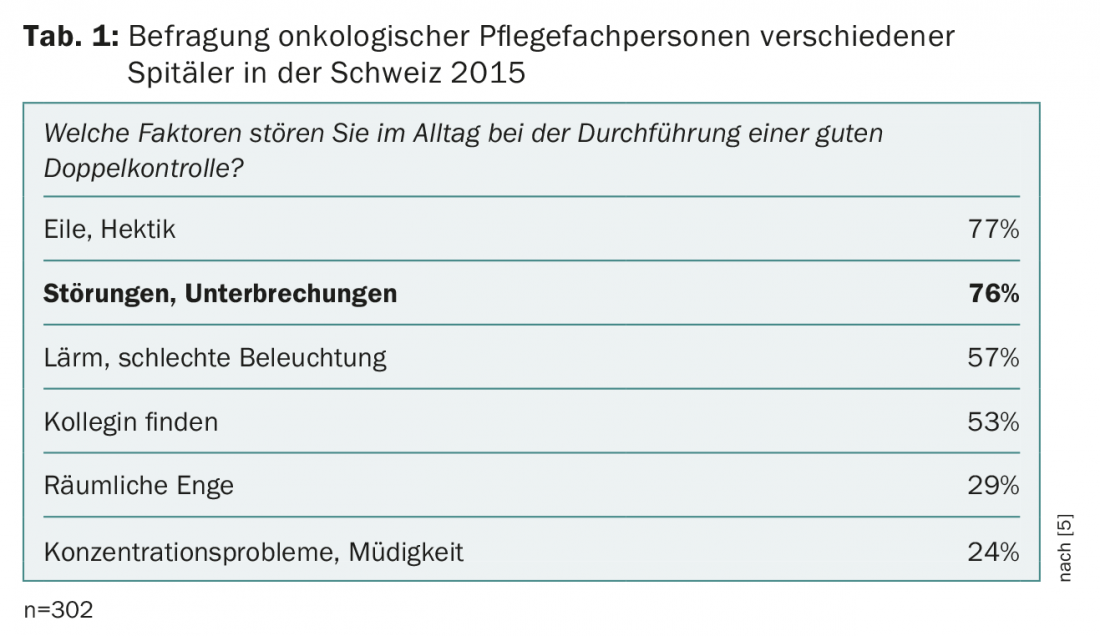

A typical problem is interference with high-risk processes such as the prescription and administration of chemotherapy. Interruptions are associated with an increase in clinically relevant errors [3]. According to a Canadian study, oncologists are interrupted an average of eight times per hour when prescribing medications [4]. In a survey, nurses in Switzerland also reported interference with dual control of oncology medications (Table 1) [5].

In summary, it is important to note that a great many resources are invested in the safety of medications, but comparatively few in the safety of the organization of care, such as the medication process. Unlike other high-risk areas, the health care system still relies too heavily on individuals’ unrestricted capacity. However, it is not enough to look for faults in the individual. Adverse events usually have several causes.

Processes

Unclear and inconsistent processes, for example, are a major cause of medication errors. Reducing unnecessary variation in processes and procedures is a key characteristic of so-called high reliability organizations. Because many developments cannot be accurately predicted, a high degree of flexibility in healthcare is essential. Nevertheless, it offers the opportunity to clearly regulate recurring processes (e.g. the adjustment of ordinances). Especially in outpatient clinics with high patient frequency, often not all persons are informed about therapy adjustments. For example, the nurse may start from the original medication while the physician has already discussed an adjustment with the patient. Analyses of adverse events show that such situations, typically associated with different process rates (completion of consultation with dose adjustment and transfer of the patient to the nurse for therapy), often undermine existing safety barriers.

In a clearly defined process, current medication changes must be explicitly communicated as changes in addition to the written prescription, and knowledge levels about next steps must be reconciled before the treatment process continues. To ensure this, it can be specified, for example, that communication must still take place before the patient in question leaves the consulting room. This prevents the attending physician from being delayed on the way to a new patient or task, or forgetting to release or communicate the change in prescription [6].

Clear guidelines on the implementation of security measures such as double checks are also important. While double-checking is becoming more prevalent in both prescribing and judging, there is often a great deal of confusion about how to implement effective double-checking. On a day-to-day basis, this results in the process being very different and usually more of a “joint control” than an independent control by two people. However, double-checking is only effective if the person checking the medications does so in an expectation-free manner. Otherwise, confirmation bias (“we see what we expect”) and responsibility diffusion easily occur.

Technology

Central, effective measures to prevent incidents are technical or technological barriers. This includes, for example, the use of barcodes for patient wristbands, high-risk medications and blood products to avoid mix-ups. The complete elimination of bolus injections of vincristine to prevent fatal intrathecal misapplications is a good example of a “strong” technical measure. The consistent switch to short infusions (“mini bags”) makes confusion between iv and ith accesses and the resulting dangerous misapplication virtually impossible. Despite the recommendation of many international expert organizations and the WHO, the switch to short infusions is unfortunately far from being implemented everywhere [7,8]. More often, people rely on rather “weak” measures such as the use of warnings or defaults. However, these are barriers that can be overlooked or circumvented in everyday life. Unfortunately, the past shows that even highly qualified and motivated professionals can make such mistakes.

Culture

Another resource for improving patient safety is a strong safety culture. In practice, hierarchies often hinder an open exchange. We were able to show in a study in Switzerland that many professionals in oncology do recognize dangers in their environment, but often do not address them in their team [9,10]. In order to promote an open discussion of mistakes (“speak up”), the backing of the leaders is central – they should encourage an open exchange about (near-)mistakes in the team. In doing so, teams should not only look at historical situations, but identify future threats through risk analysis. One possible vessel is clinical safety conferences, in which clinicians and patient safety experts discuss specific hazards in everyday life and jointly develop solutions. Patient involvement can also help improve patient safety. Many oncology patients are concerned about their safety and are willing to engage to the extent of their ability and competence [11]. In particular, it is important that patients are encouraged to address potential errors (e.g., patient mix-up) directly [12]. A corresponding change in culture takes time and commitment from all those involved, but does much to increase safety.

Errors are not completely avoidable even in oncology care. But we can work together to make the system as resilient as possible.

Take-Home Messages

- Complex systems of care put patients at risk.

- To increase patient safety in oncology care, standardization of procedures, processes, and information (e.g., handoffs, duplicate controls), technical and technological solutions (e.g., barcodes, vincristine no longer bolus with Luer lock compatibility), culture change (e.g., “speaking up,” patient involvement) are needed.

Literature:

- Quaresma M, Coleman MP, Rachet B: 40-year trends in an index of survival for all cancers combined and survival adjusted for age and sex for each cancer in England and Wales, 1971-2011: a population-based study. The Lancet 2015; 385: 1206-1218.

- Mattsson TO, et al: Non-intercepted dose errors in prescribing anti-neoplastic treatment: a prospective, comparative cohort study. Annals of Oncology 2015; 26: 981-986.

- Trbovich P, et al: Interruptions During the Delivery of High-Risk Medications. Journal of Nursing Administration 2010; 40: 211-218.

- Trbovich P, et al: The Effects of Interruptions on Oncologists’ Patient Assessment and Medication Ordering Practices. Journal of Healthcare Engineering 2013; 4: 127-144.

- Schwappach DL, Pfeiffer Y, Taxis K: Medication double-checking procedures in clinical practice: a cross-sectional survey of oncology nurses’ experiences. BMJ Open 2016; 6(6): e011394. DOI: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011394.

- Bunnell CA, et al: High performance teamwork training and systems redesign in outpatient oncology. BMJ Quality & Safety 2013; 22: 405-413.

- Hoppe-Tichy T, Horscht J, Schöning T: Accidental intrathecal administration of vincristine. Hospital Pharmacy 2010; 31: 181-187.

- Gilbar P, Chambers CR, Larizza M: Medication safety and the administration of intravenous vincristine: international survey of oncology pharmacists. Journal of Oncology Pharmacy Practice 2015; 21: 10-18.

- Schwappach DL, Gehring K: ‘Saying it without words’: a qualitative study of oncology staff’s experiences with speaking up about safety concerns. BMJ Open 2014; 4: e004740.

- Schwappach DL, Gehring K: Frequency of and predictors for withholding patient safety concerns among oncology staff: a survey study. European Journal of Cancer Care 2015; 24: 395-403.

- Schwappach DL, Wernli M: Chemotherapy Patients’ Perceptions of Drug Administration Safety. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2010; 28: 2896-2901.

- Schwappach DL, Frank O, Hochreutener M: Avoiding mistakes – Help us! Your safety in the hospital. Zurich: Patient Safety Foundation. 2010.

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2017; 5(5):24-26.